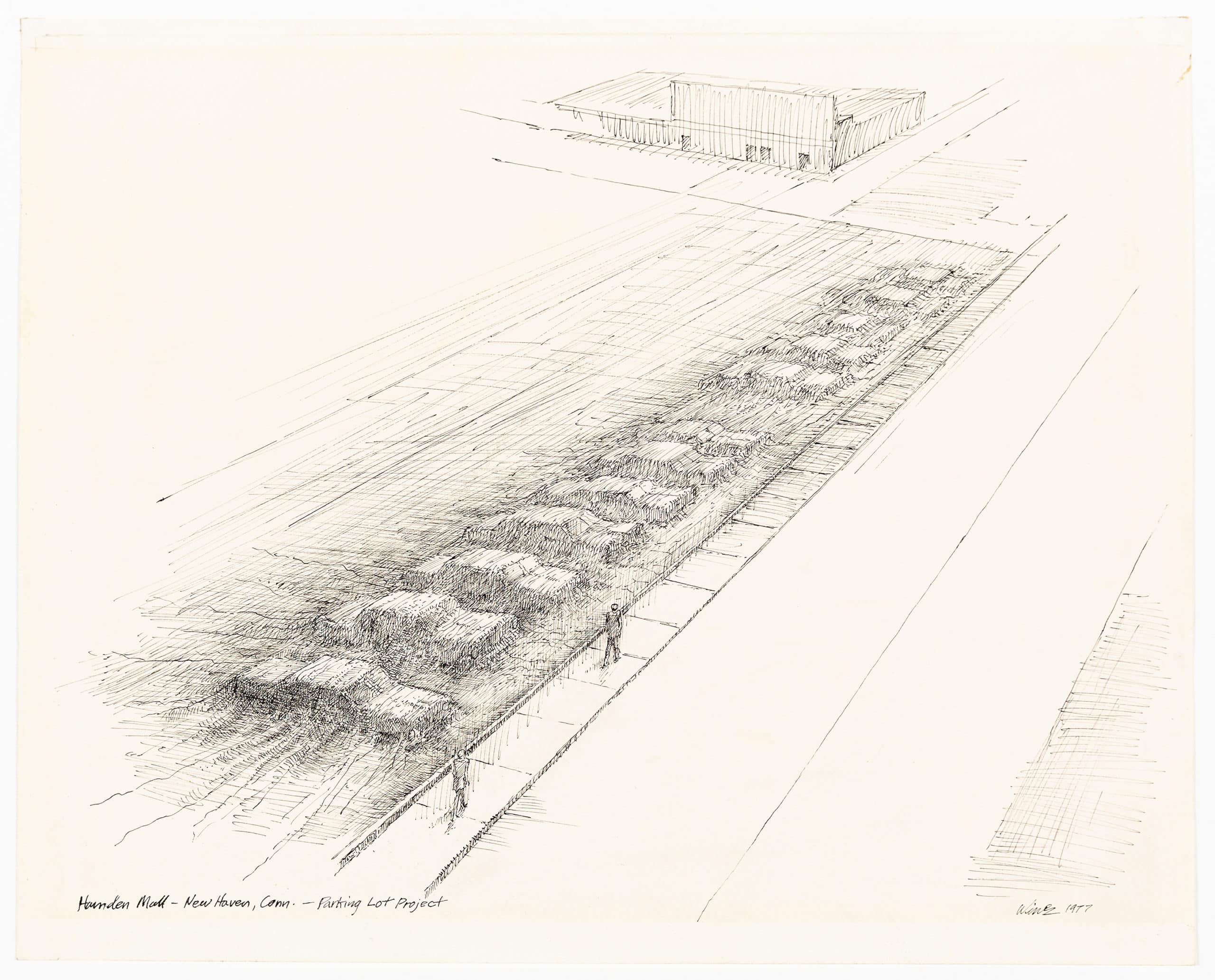

James Wines: Ghost Parking Lot

This drawing depicts a site-specific public art project, commissioned by the retail developer David Burmant, which entombed twenty junked cars under a layer of asphalt in a suburban shopping plaza. James Wines was interested in upending expectations about common iconographic elements of suburbia by inverting the relationship between such objects and their context. In this reconfigured relationship, a certain permeability invades the surfaces of the given object from without, often to the point where the site seems to be redressing the object’s incursion. In the case of the Ghost Parking Lot drawing, this conceptual approach is reinforced through the graphic communication. A graphic indeterminacy between the various forms in the image is achieved through Wines’ use of a hatching technique.

Hatching in architectural drawing is a technique that can be used to clearly differentiate and codify surfaces. Used to fill in a surface defined by an outline, the hatch can clarify materiality and contribute an additional type of visual information. However, the hatch is an ambiguous drawing technique, and in Wines’ hands it serves to conflate difference—blurring distinctions between varying materials and surfaces. The two figures trudging down the sidewalk cast crosshatched shadows that appear indistinguishable from the cement surface from which they seem to have emerged. The cars rise out of a crosshatched morass with very little outline to distinguish them from the rest of the asphalt parking lot. Similarly, the big box store hovering at the edge of the parking lot is hatched in much the same way as the parking lot itself—merely another barely distinguishable component of this suburban quagmire. The hatching overtakes the drawing, just as the parking lot overtakes the parked cars.

At a time when much architectural drawing concentrated on clear and precise line work, Wines’ approach is pointedly focused elsewhere. Crisp lines that coherently communicated not only an analytical procedure but also an entire linguistic system were a key feature of formalist architectural drawing of the 1970s. Wines’ murky lines stand in marked contrast to such didactic clarity. While contemporaneous formalist drawings wield their hard edges to analyse and decompose architectural objects with the knife-edge precision of a surgical procedure, Wines’ drawings use a duller tool, the muddy crosshatch, to speculate how such architectural objects inhabited their own environments.