Johan Celsing Buildings Texts (2021) – Review

‘Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the handing on of the fire’

Gustav Mahler quoted in Johan Celsing Buildings Texts

The work of Johan Celsing represents the continuation of a tradition of significant twentieth century Swedish architects into the present. While the influence of Gunnar Asplund, Sigurd Lewerentz and his father Peter Celsing loom large in his work, his own unique contributions to contemporary Swedish architecture address the new realities of construction, and a changed society and profession, with a finely judged poetic pragmatism. Celsing is a rare presence in Swedish architecture – perhaps one that stands somewhat outside fashionable movements. He has pursued his own quiet path in architecture described in his article ‘The Robust, the Sincere’ published in Nordic Architects Write, 2008. He argues that ‘resisting the seemingly radical and visually determined impulses of architecture opens up other possibilities for linking today’s buildings to those of earlier periods’.

Johan Celsing Buildings Texts is a weighty and comprehensive monograph of his oeuvre spanning the decades from 1985, including his first project: The Nobel Forum, to today, taking in an impressive array of projects of all scales and programmes, private and public, secular and sacred. Although several buildings have been extensively published in international journals, this book is the first critical and, unusually, deeply personal reflection of a life in architecture. At its core, the monograph provides a comprehensive portrait of 30 projects including drawings from the site to the construction detail, sketches, illustrations, fine photography by Ioana Marinescu, models and generous descriptions. What sets it apart is in the promise of the title, a series of texts that go deeper into the projects and beyond, reflecting on life, art and poetry.

Architectural monographs rarely give a glimpse of the soul of the practitioner as an artist, yet this book does in its biographical detail. It contains several essays by Celsing himself, including his Notes at the end about being an architect’s son and his father’s sudden death, which prompted him to become an architect himself. His father Peter Celsing was one of the most important architects at the height of Swedish social democracy. His ensemble of the City Theatre, the Kulturhuset on Sergels Torg, which served as a model for the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the bank of Sweden (1966 -1974) is situated in the very centre of Stockholm and is part of a huge infrastructural, cultural and political project.

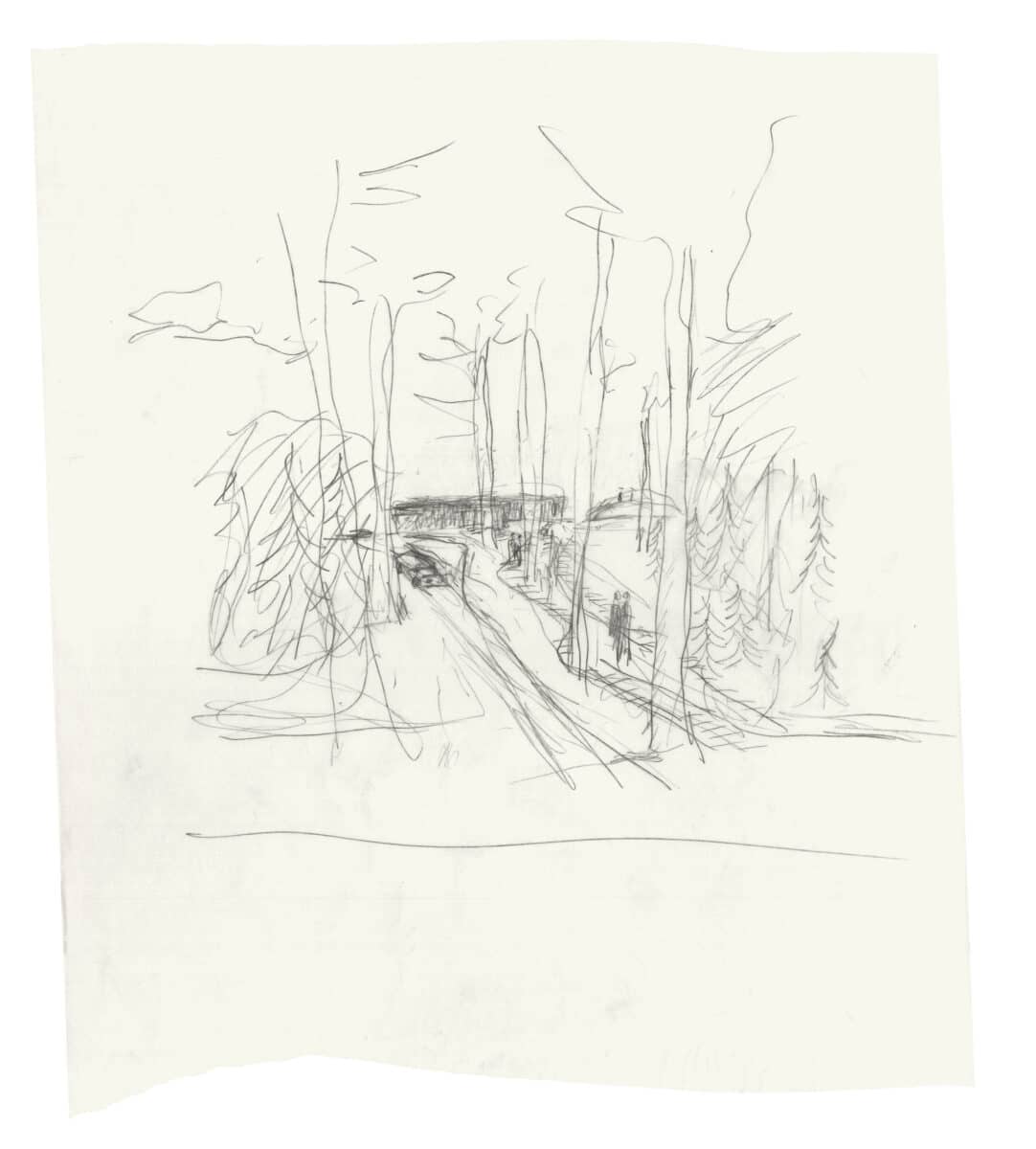

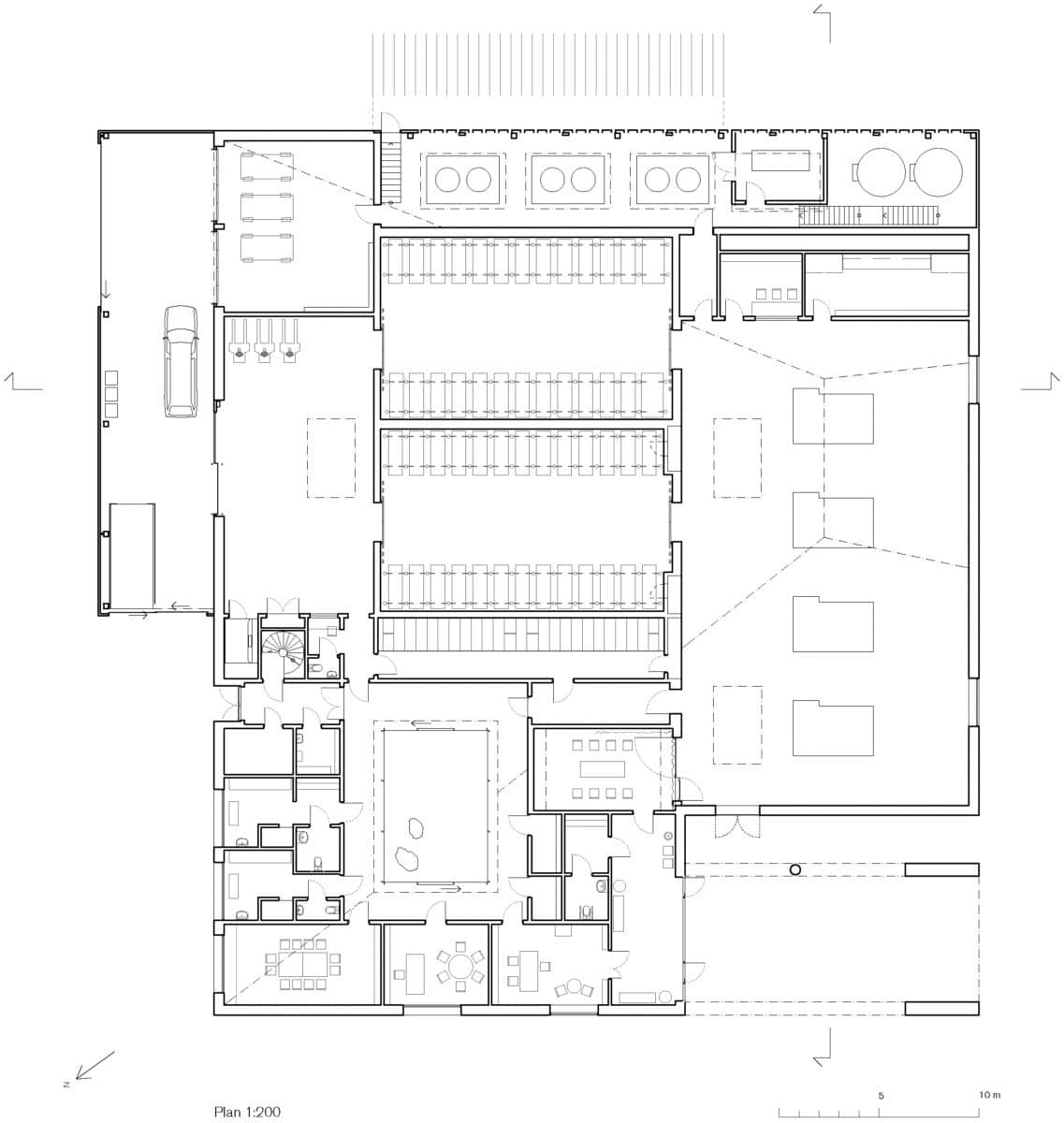

Celsing famously recites poems by heart. In his text, ‘Plans, Metres: How the Work of Poets May Inform the Crafting of Buildings’, he elaborates on ideas of patterns, order and rhythm with reference to the plan drawing. ‘The two-dimensional abstractions of architectural plans are not unlike the metrical patterns [Plans & Metres] that distinguish poetry’ he writes, arguing that ‘a certain structure and rhythm are necessary in a building to make it accessible to everyone’ while being careful to balance order and structure with looseness. Without looseness, the architecture can become dry, he says.

The rhythm of the book is structured around alternating texts and project pages. It starts with essays by Wilfried Wang and Claes Caldenby, which establishes an academic perspective to this project of continuity. In ‘Appropriate Architecture in an Uncertain Age’, Wang discusses integrity, appropriateness and poiesis, in the context of life, a changing society and the slow translation of an architecture project from conception to realisation. ‘The Integrity of an architectural work can be understood to reside, imminently, in the relationship of the elements of the design to one another as well as to the overall object’, he writes. The poiesis is the cultural measure of the creative process in opposition to the corporate measure of productivity.

The careful negotiation between artistic ideas free of constraints and external realities is what Celsing he brings to his projects, and what drives his creative process. He goes deeply into methods of construction to inform the architectural language. The way in which he exploits a new economy and construction reality today achieves this idea of the ‘robust and sincere’ as well as a material richness. For example, in the Brick Tower in Malmö, he uses repetition, subtle variations, a few carefully considered typical assembly details and a resourcefulness towards what modern technology can do. Sliding bridges allow the masonry brickwork to be laid by hand in situ, a creative realism that echoes the expressive structures and ornaments of Louis Sullivan’s industrially produced buildings. There is innovation in finding a kind of poetry in a big building with a modern construction. In her review, Malmö-based architect Katarina Rundgren describes this building: ‘the slender, 19-storey brick building with its facade of massive red Danish brickwork is an apartment block [and] a kind of magnified Roman tenement that conjures up early 20th century Manhattan. While many of Malmö’s new buildings … are ostentatious with their spectacular concepts, it just stands there with its almost drab facade and takes it easy’.

Celsing is not interested in the spectacular but in architecture that belongs more to the background of the city while being enjoyed in its tactility close-up, by those who inhabit it. This reflects his admiration for the work of Austrian architect Herman Czech, who argues that ‘architecture is background and should only speak when it is spoken to’.

Caldenby, in his essay, ‘The Double Imperative’, reflects on form and function as discourse before describing the intense negotiation between these antagonists in complex projects by Celsing, such as Årsta Church, the large housing projects and the New Crematorium. Celsing’s addition to Asplund and Lewerentz’s Woodland Cemetery, a UNESCO world heritage site, which replaced ageing back-of-house technical areas of the crematorium, is one of his most important projects and is given 27 pages in the book.

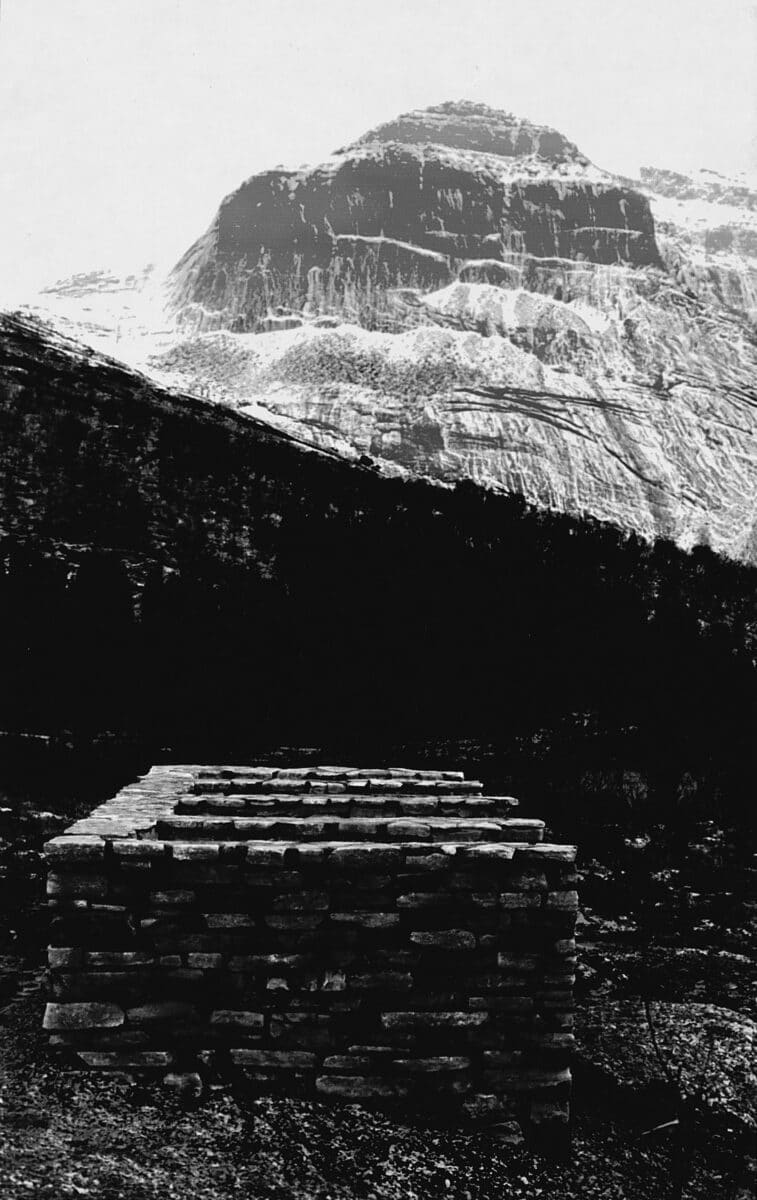

The slow transformation of the design from the competition entry to project realisation involved defining an appropriate appearance for a crematorium, which in its final purple-brown brickwork alludes to the rough bark of the surrounding pine woodland. Located in a clearing, the competition entry ‘A Stone in the Forest’ (2009) impressed the jury by not repeating or mimicking the earlier buildings, except perhaps for the incidental relationship to the strange mound and funerary crypt outside Asplund’s Woodland Chapel. It also involves balancing appropriate spaces for mourning while making a good environment for those who work there, all within tight budget constraints. A creative example of this negotiation or friction, is the use of precious materials – sparingly, opportunistically and sometimes unexpectedly. The floor of the Great Furnace Room, which is usually confined to the back-of-house, is covered in Swedish green marble. The end wall of the small Ceremony Room is dressed in perforated, white-glazed bricks, which serve both visual and acoustic purposes. The care in lining and dressing spaces follows the work of Àlvaro Siza as well as the Viennese architects Adolf Loos and Josef Frank, who were interested in fabrics and textiles to provide warmth and comfort. An appreciation of a culture that goes beyond architecture is also what Celsing thinks about.

The work of Lewerentz, co-author of The Woodland Cemetery (1915 – 1940) with Asplund, is significant as a background here, the complete single-mindedness of his work and its continued significance has little to do with his sparse writing but with what he built. Lewerentz practised with complete authority over the construction process, in a time before the large construction firms that now dominate the production of architecture and buildings in Sweden. Celsing belongs to this tradition but is also affected by its demise. His work can be seen as coming to terms with these new realities of today as well as a continuation of the older traditions. In Hugh Strange’s interview with Celsing, we learn that Lewerentz was amongst a group of artists and architects, with whom his father collaborated. Their conversation focuses on the reconstruction of the canopies of the twin chapels (1943) in Lewerentz’s Malmö Eastern Cemetery.

Celsing’s Årsta Church (2011) is an example of coming to terms with a changing society. The tension of the project lies in attempting to create a sacred and transcendent space for a secular community in an acknowledgement of the diversity inherent in a contemporary Stockholm suburb. His proposal for a mosque in another Stockholm suburb is a further reconciliation of mid-century Sweden with that of today.

The interview with photographer Marinescu, ‘The Analogue World of Johan Celsing’s Buildings’, is generous and intimate. She was inspired by Celsing’s work after attending a lecture he gave at London Metropolitan University in 2007. She continues to use a large-format analogue camera, finding it appropriate to involve time in the photographing of Celsing’s work, acknowledging the duration of their realisation. As Lewerentz, he is as interested in new materials and techniques of today as he is in the ancient: architecture is ‘an intense but realistic craftsmanship’, he argues. An example of this poetic realism is a project that Elizabeth Hatz considers to be Celsing’s most mature and consummate buildings to date. She describes how the prefabricated facades of the headquarters buildings on the Swedish island of Gotland (2008) appear chiselled out of the rock, not unlike the characteristic landscape of this rugged Ingmar Bergman island. For Hatz, Celsing demonstrates that it is possible to make industrially produced buildings that appear to be crafted, and in this example even geological.

Unlike Lewerentz, who just built and did not say or write very much, Celsing reaches out, keen to have conversations. Both the Stockholm Seminar he organised in 2008 and his lifetime commitment to teaching architecture students – which the book does not talk about – represent the important role he plays in provoking a discussion amongst fellow professionals and beyond. This book belongs to that generous desire to communicate, bringing together the results of Celsing’s thinking and making as a practitioner who represents a deep continuation of an architectural tradition. It justifies the importance of his influence and approach in Sweden and extends it now outside the Nordic area.

Pamela Johnston ed. Johan Celsing Buildings Texts (2021) is published by Park Books. Copies of the publication can be purchased here.

Nina Lundvall is an architect, co-founder of Nina James Architects and leader of a masters design unit at the University of Nottingham.