DMJ – From Hearths to Volcanoes: the Armenian glkhatun

This text is the last peer-reviewed essay published in DMJournal No.1: The Geological Imagination (2023) Print copies of the Journal and subscriptions for the first three issues are now available through our online bookshop. We are currently accepting abstracts for the third issue of DMJournal. Find more information here.

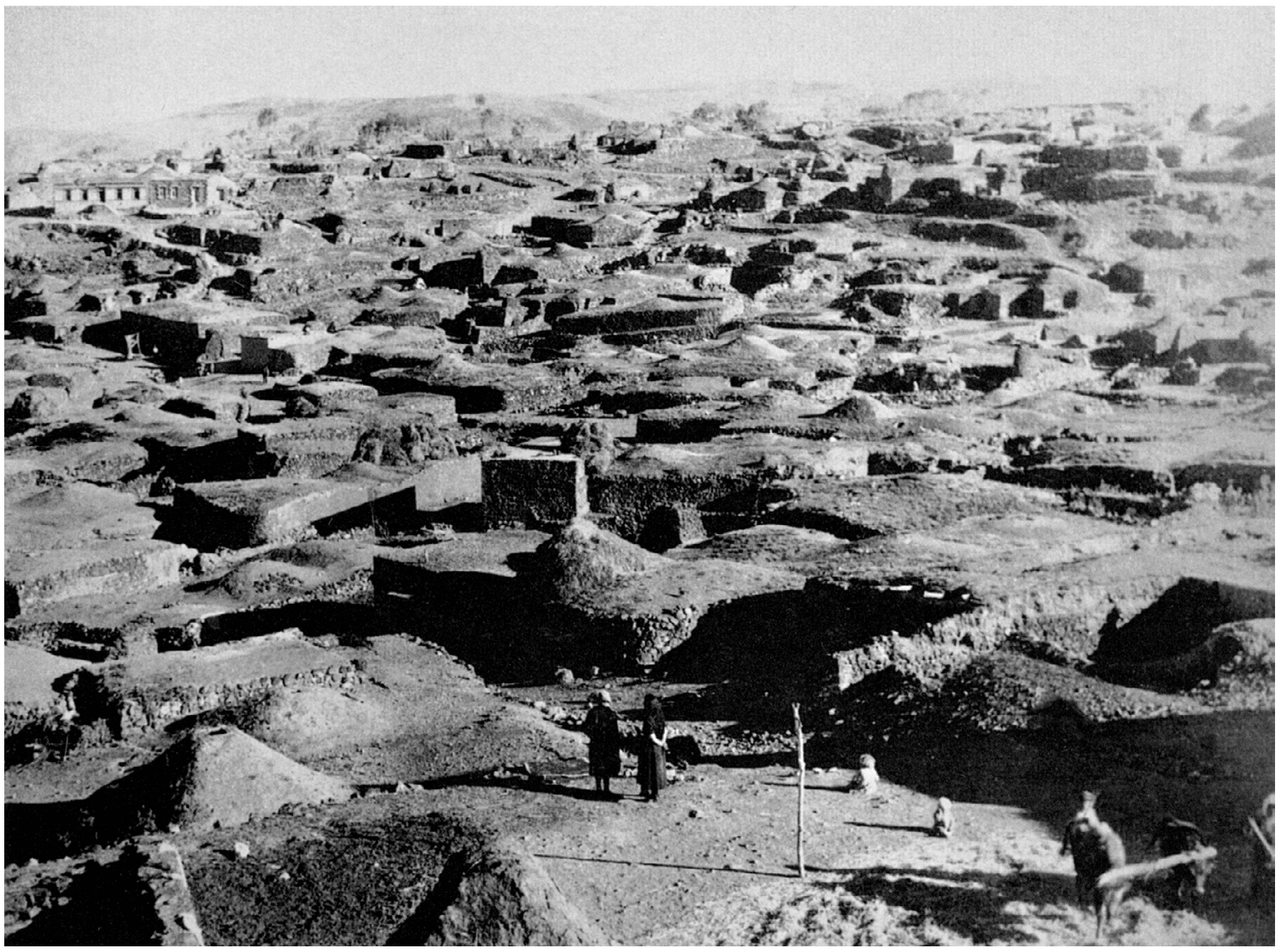

‘Often a traveller searching for the village would already be there standing on the roof of a house. Only when the forelegs of his horse became stuck in the chimney [smoke hole] or when, taken unawares, he fell inside the house and found himself settled by the family circle, did he figure out that he had arrived.’

– General von Moltke, 1851

The glkhatun, literally ‘head house’ in Armenian, consists of a large rectangular room, often carved deep into the side of a slope, with a hard earthen floor bordered by retaining walls of volcanic rock and no openings other than the door and the yerdik – an oculus through which the smoke arises from the hearth. Glkhatuner are already known for the structural properties of their hazarashen, a complex wooden roof, which scholars regard as the precursor of early Christian church domes. This paper is less concerned with the structural capacities of this subterranean construct than with myth and the cosmology that finds embodiment in it. Its aim is to explore the imaginative associations between these dwellings and the volcanic landscape in which they are located, and the inter-relations between geological time and human life.

It is hard to resist the formal comparison between the vernacular structure, already described by Xenophon during his passage through western Armenia in the fifth century BCE, and Mount Ararat, with its ring of volcanic vents. Because of its mass, Ararat appears omnipresent in the landscape. Although visible from many sites in present-day Armenia, and geographically close, the mountain lies within the borders of present-day Turkey. The volcano has become ever more present in Armenian iconography as a source of mythological identity. While this comparison may seem anecdotal, I argue for the importance of assessing the glkhatun across multiple scales beyond that of the building: from a territorial perspective, examining the geomorphology surrounding and formed by the ‘head house’ settlements; a resource-based perspective, exploring material history through acts of making; an environmental perspective, investigating the material flows between people and the environment; and a talismanic perspective, identifying the ways in which the assembly of architectural elements not only serves a function, but embodies the collective and cross-generational imaginary of a place.

All these perspectives are intertwined across scales. The glkhatun, beyond the architectural object, becomes a lens through which the ramifications unfold: the view from below, starting with the hearth as the epicentre of the family group; the dome that delimits the living space and involves both the structural and talismanic; the dwelling that grows organically as the family expands. Once past the oculus, the view from above allows a topographical reading of the assembly of ‘head houses’; finally the arrival at the mountain, which transcends both the time and space of empires and nation-states, brings us closer to the geological and cosmogonic source of the glkhatun.

Could we consider the whole of the glkhatun structures and the tangle of interior spaces that form these underground settlements as material drawings in their own right? This presupposes an architecture of attunement, one that reveals, as much as rewrites, the geological clues of the undulating terrain and supports the argument that – alongside wind, water, gravity and volcanic activity – human dwelling is a geomorphological force. In the age of the Anthropocene and as Armenia once again finds itself in the grip of armed conflict, the unique architecture of the glkhatun is not only a marvel of landscape implementation that takes advantage of the geological reading from which it was born, but is also something that raises political awareness and implies a territorial dimension which, by virtue of its temporality, is transnational.

Download the full article as a printable PDF

DMJournal–Architecture and Representation

No. 1: The Geological Imagination

ISSN 2753-5010 (Online)

ISBN 978-1-9161522-3-6

About the author

Guillaume Othenin-Girard is an architect and an assistant professor in the Department of Architecture at the University of Hong Kong. His teaching and research focus on the cross-disciplinary potential between archaeology and architecture. He is currently developing an interpretive planning strategy for Armenia’s Vedi River Valley that includes the collaborative design of an archaeological field laboratory. In 2018 he led the design and fabrication of ‘A Room for Archaeologists and Kids’ for the Museum of Pachacamac, Peru and is the co-author of Pachacamac Atlas (2022). Guillaume is interested in how the transformative agency of drawing carries the potential to maximise breadth of participation throughout the stages of planning, designing and building a vision that considers the landscape as a source of heritage in itself. He is the co-founder of Architecture Land Initiative, a cooperative that works closely with political actors and NGOs at the local and national scale to enact sustainable and equitable transformation of landscape, public space, and architecture.