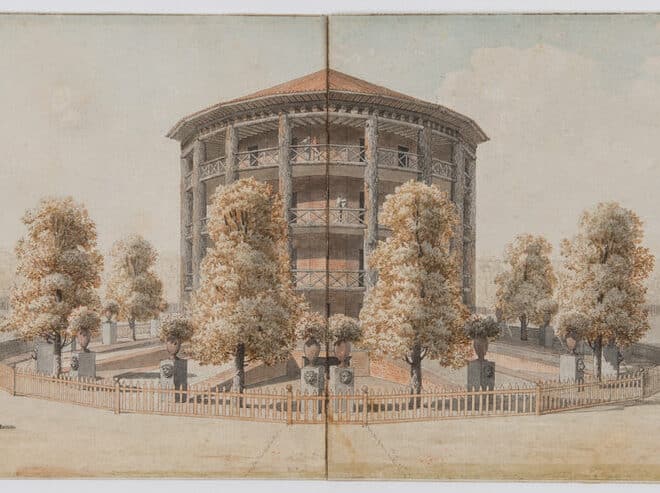

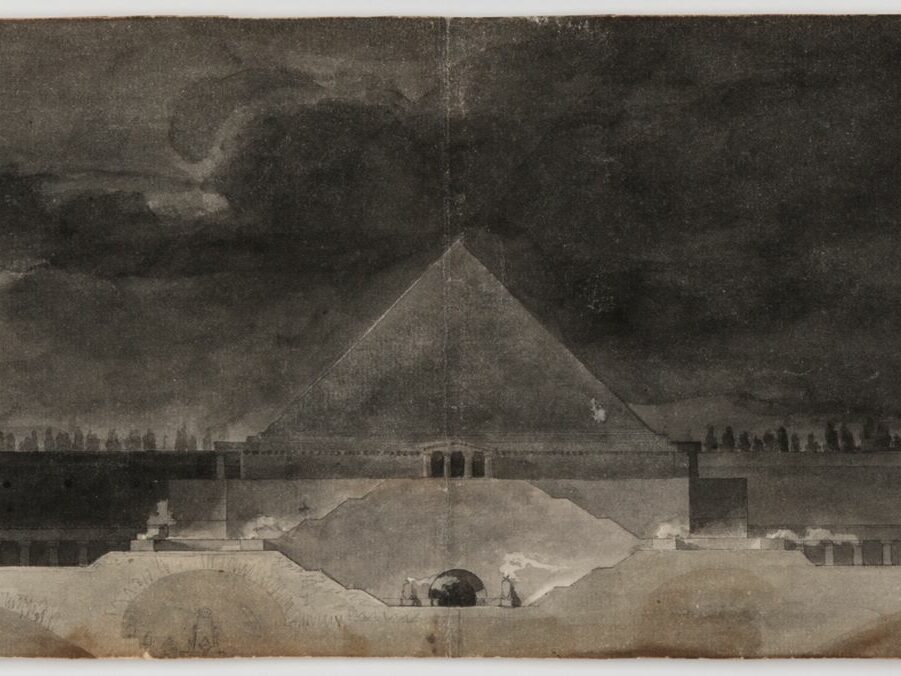

A Civic Utopia: Architecture and the City in France, 1765-1837

8 October 2016 – 8 January 2017, The Courtauld Gallery

Curated by Nicholas Olsberg and Basile Baudez, organised by Drawing Matter Trust in collaboration with The Courtauld Gallery as part of Somerset House’s celebration of the 500th anniversary of Thomas More’s Utopia.

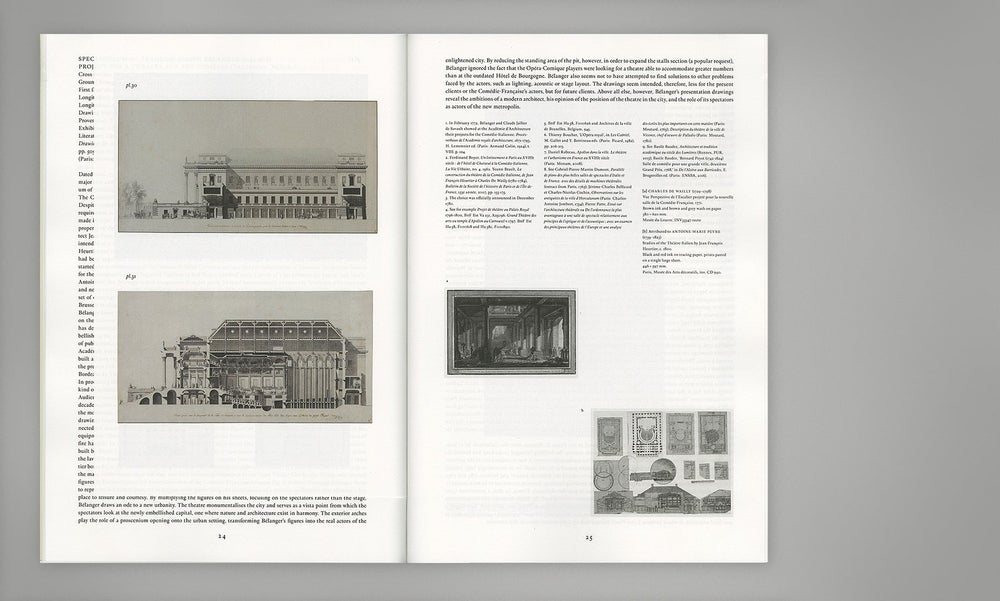

The exhibition considered the place of architecture in establishing the notion of public life, bringing together a selection of ideas for public building and public space from the late Ancien Regime to the early years of Louise-Philippe that suggest the ideal of a ‘scientific’ city, in which rational, hygienic and symbolic expressions of civic life established a pattern for the improvement of society.

Seven Concepts

The Civic Utopia exhibition was organised around seven concepts that were central to the Enlightenment view of an ordered, liberal community:

Porta looked at the city limits through a series of cabinet drawings that celebrate the metropolitan grandeur of an ordered waterfront (a model followed by William Chambers here at Somerset House); the enjoyment of movement and promenade as open space in the approaches to the city replaced its walls, inhabited bridges, and citadels; and the new dignity accorded to hygienic functions such as hospitals or burial grounds as they moved to its perimeters.

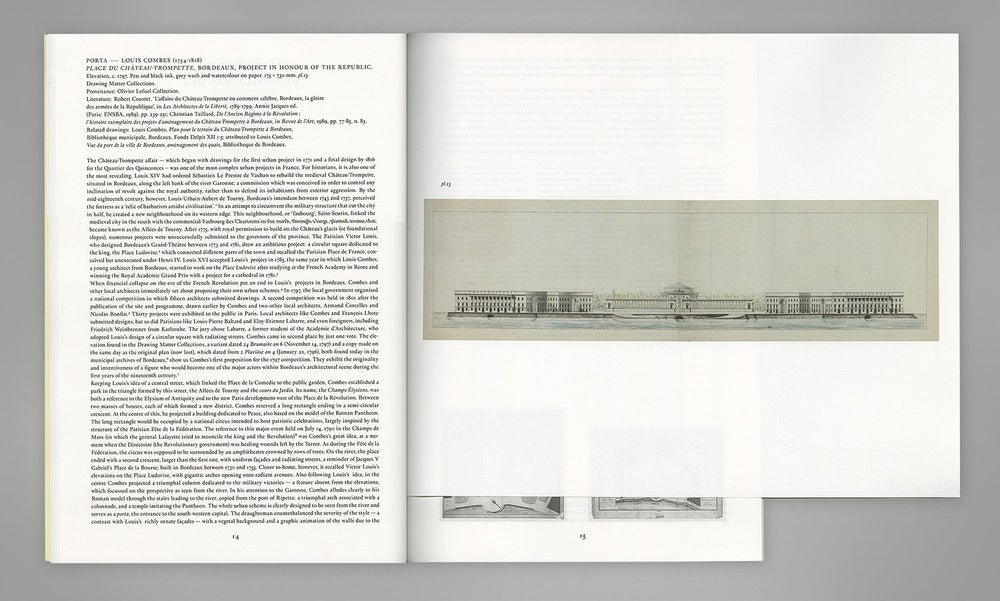

Lexicon presented two examples of the new urban vocabulary, evolving in France from Roman precedents, and of its impact on the world at large. A proposal for a French cemetery in Rome that echoes ancient forms; and a selection of model projects from the circle of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts that show the distinctive language developed for the different building types of a secular, civil society.

Ratio showed how buildings reflect the Enlightenment’s confidence in reason, measure and knowledge, both symbolically (as an imaginary temple to art, knowledge, and reason rises amidst the disorder of the medieval town), ideologically (in the consolidation of artistic and scientific institutes into a single palace of learning) and instrumentally (through such vehicles as the mint or bourse which brought system into the regulation of exchange.)

Lex suggested the central place of public order, civil regulation, and the rule of law in the construction of a just society, and the determination to represent their fundamental role in asserting the rights and duties of the citizenry, both in the prominence of the buildings to service them and through their iconography.

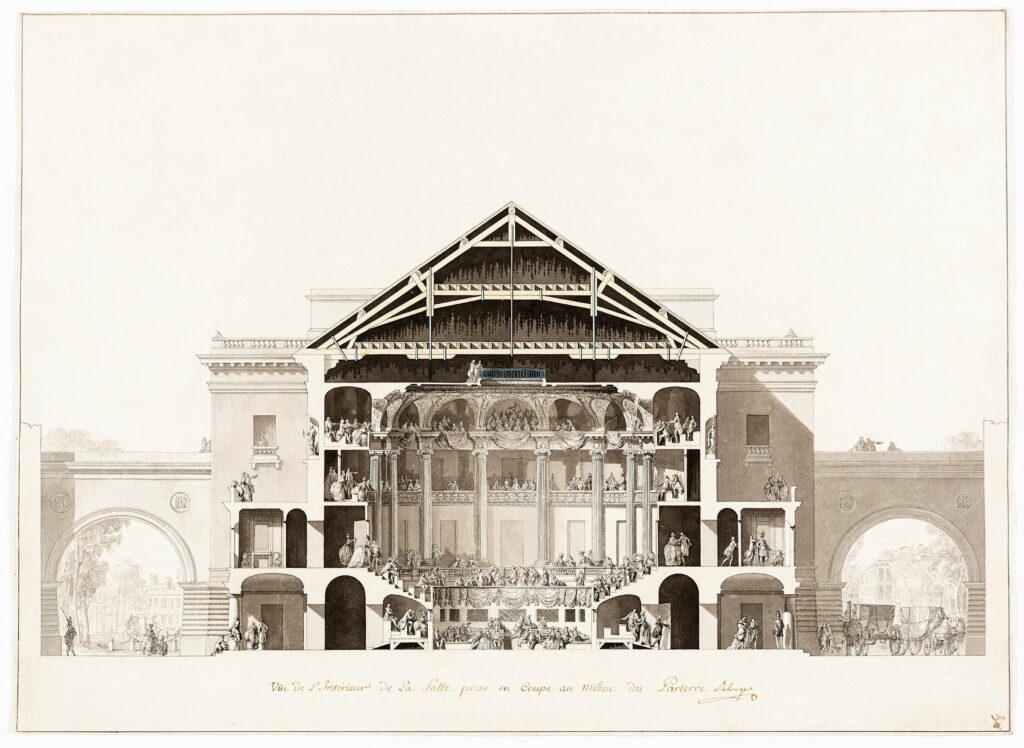

Spectaculum was concerned with the embellishment of the city as a place of pleasure, not just in the increase in the scale and range of its sites of social intercourse, but, in its newly ordered grace, as a spectacle and an architectural landscape of delight in its own right.

Sanitas, or the notion of civic hygiene, looked at the regulation of commerce for the benefit of public health and convenience, taking the particular example of processing and trading in perishable goods through raised, well-aired, watered, and open markets.

Exemplum showed the dissemination of this civic language and its aspirations as they moved from the academy to the ground, and from regional capitals to the provincial town, in a selection of public building projects developed in the early 1830s by a recent graduate of the Ecole des Beaux Arts for the small Burgundian city of Macon.

The drawings that carried these ideas mark one of the high points of architectural expression. The models developed in France show an ‘august simplicity’ that the English tastemaker Horace Walpole urged upon his countrymen and established learning methods, architectural characteristics, monumental typologies, and a sense of city as the embodiment of common principles that travelled the world in the century that followed. They still have much to say to us as we reinvent, embellish and reconsider the structure of the cities we wish to inhabit in our own time.

– Nicholas Olsberg and Basile Baudez

To coincide with the exhibition Drawing Matter published a large format, finely illustrated book, A Civic Utopia: Architecture and the City in France, 1765-1837.

Related Reading