Trevor Dannatt: St Mary’s Grove

When my father, the architect Trevor Dannatt, died in 2021 at the solid, pleasingly palindromic, age of 101, he left considerable stuff. He had kept a long, longhand daily journal all his life; he tried to do a drawing a day in his sketchbook; he liked to take notes and citations from his extensive reading, and had always been a keen photographer, usually of buildings, both vernacular and celebrated. And that was nothing compared to the abundant physical residue of his professional life: voluminous correspondence, bills, proposals, drafts, revisions, receipts, stretching back to student days before the war.

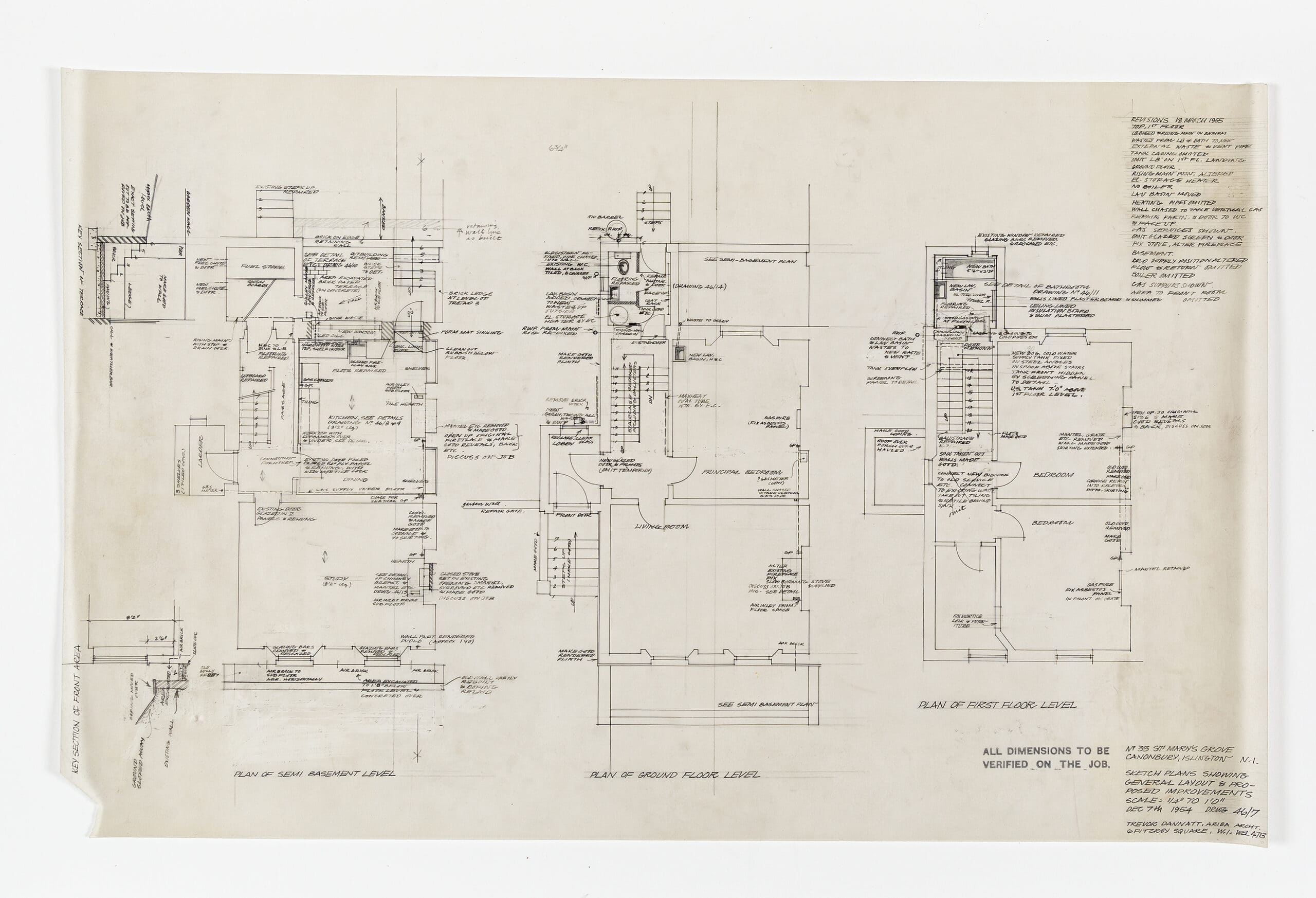

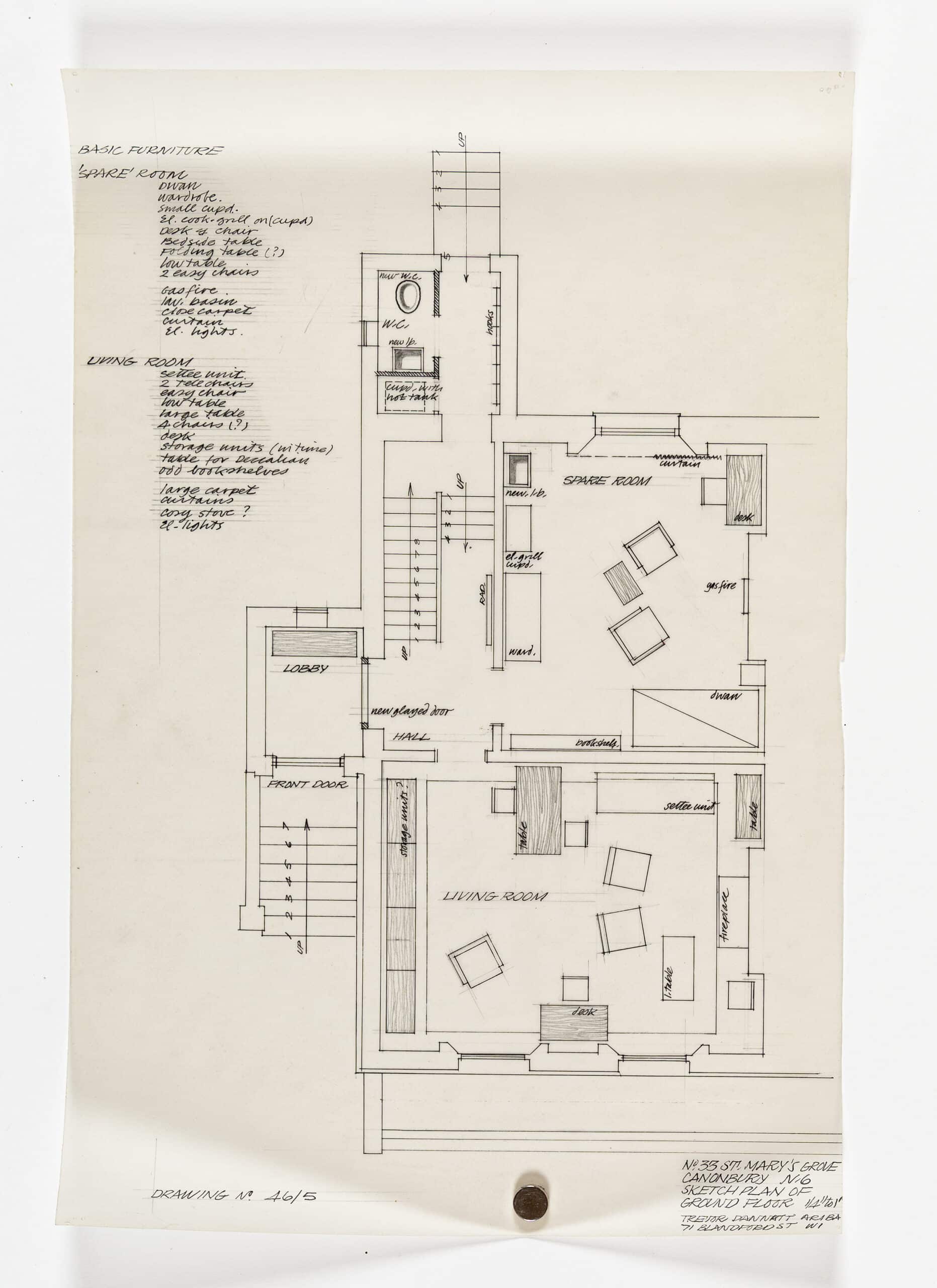

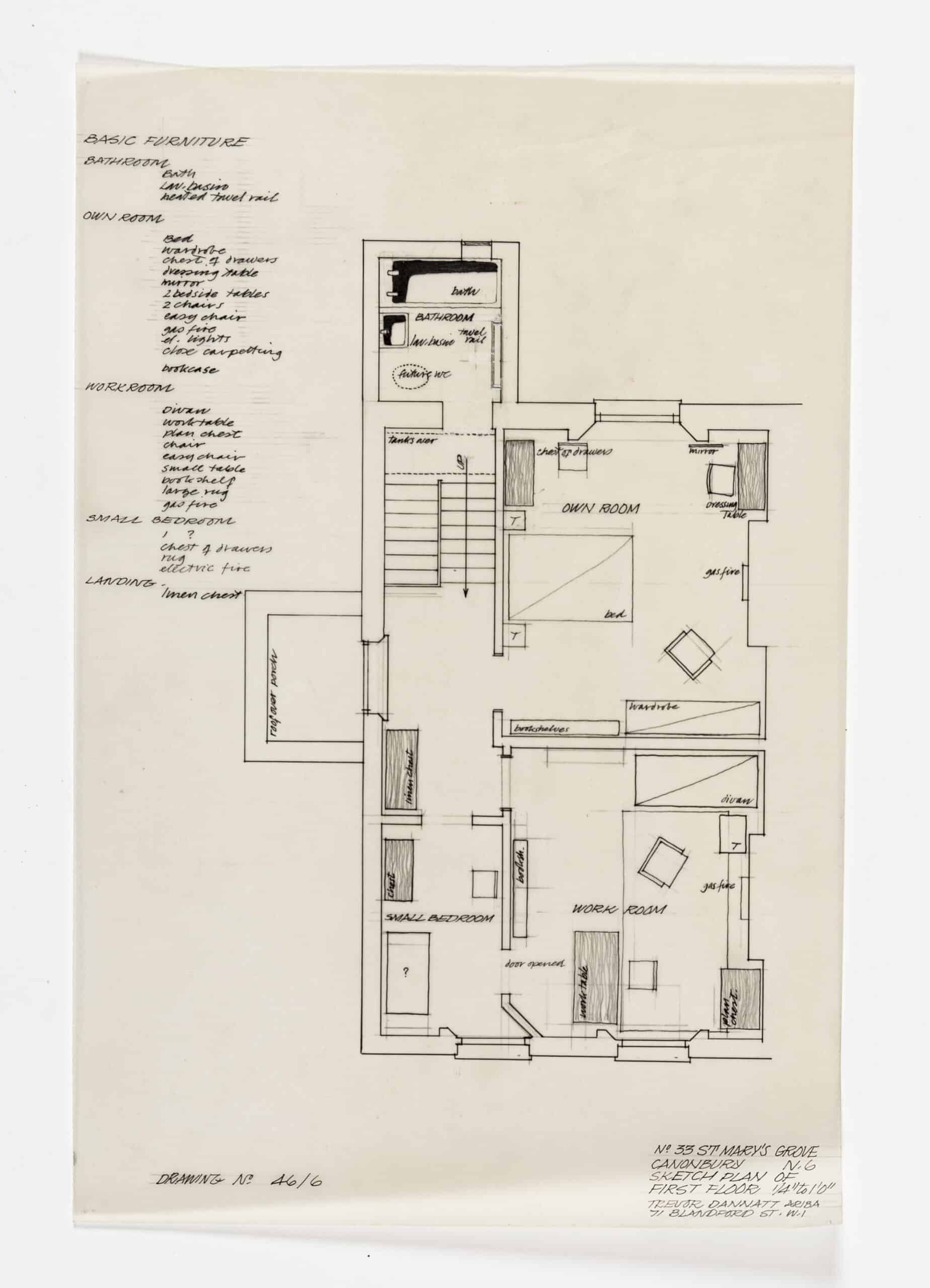

But perhaps of greatest importance, and certainly greatest physical bulk, annoyance, were his architectural drawings, originals and blueprints, rough on-site sketches, conceptual mappings, precise measured instructions for doorknob details, even proverbial napkin doodles. My father loved to draw and seemingly drew everything, and they were piled up everywhere, most notably (and alarmingly) in countless rolls and canisters and storage tubes.

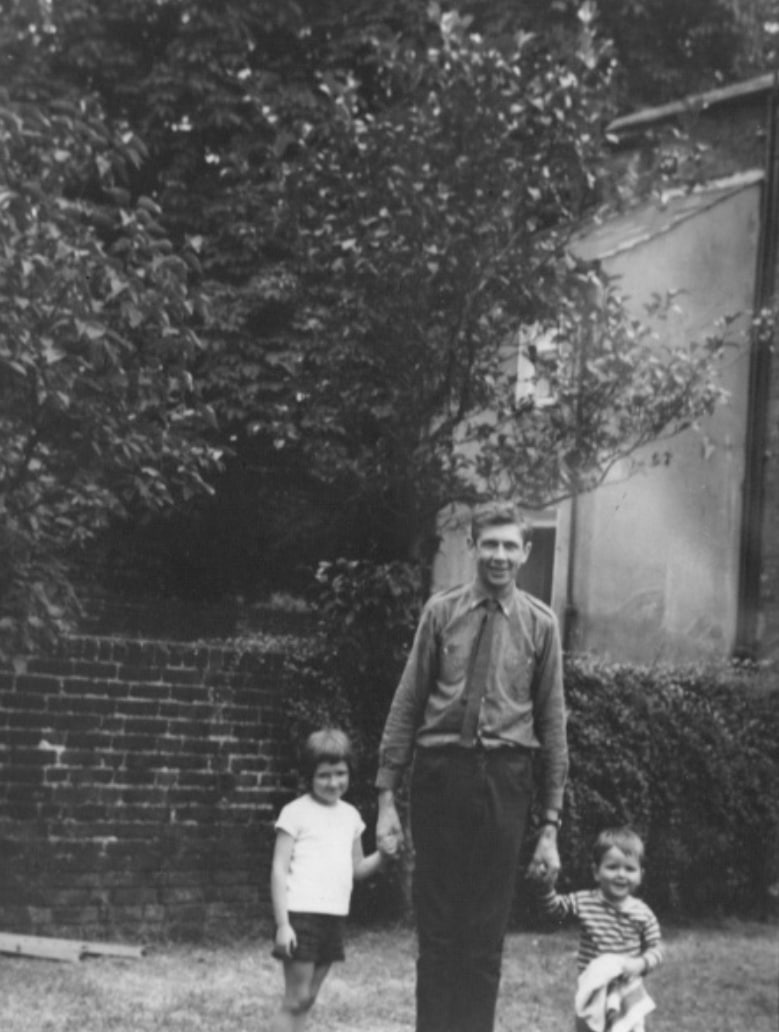

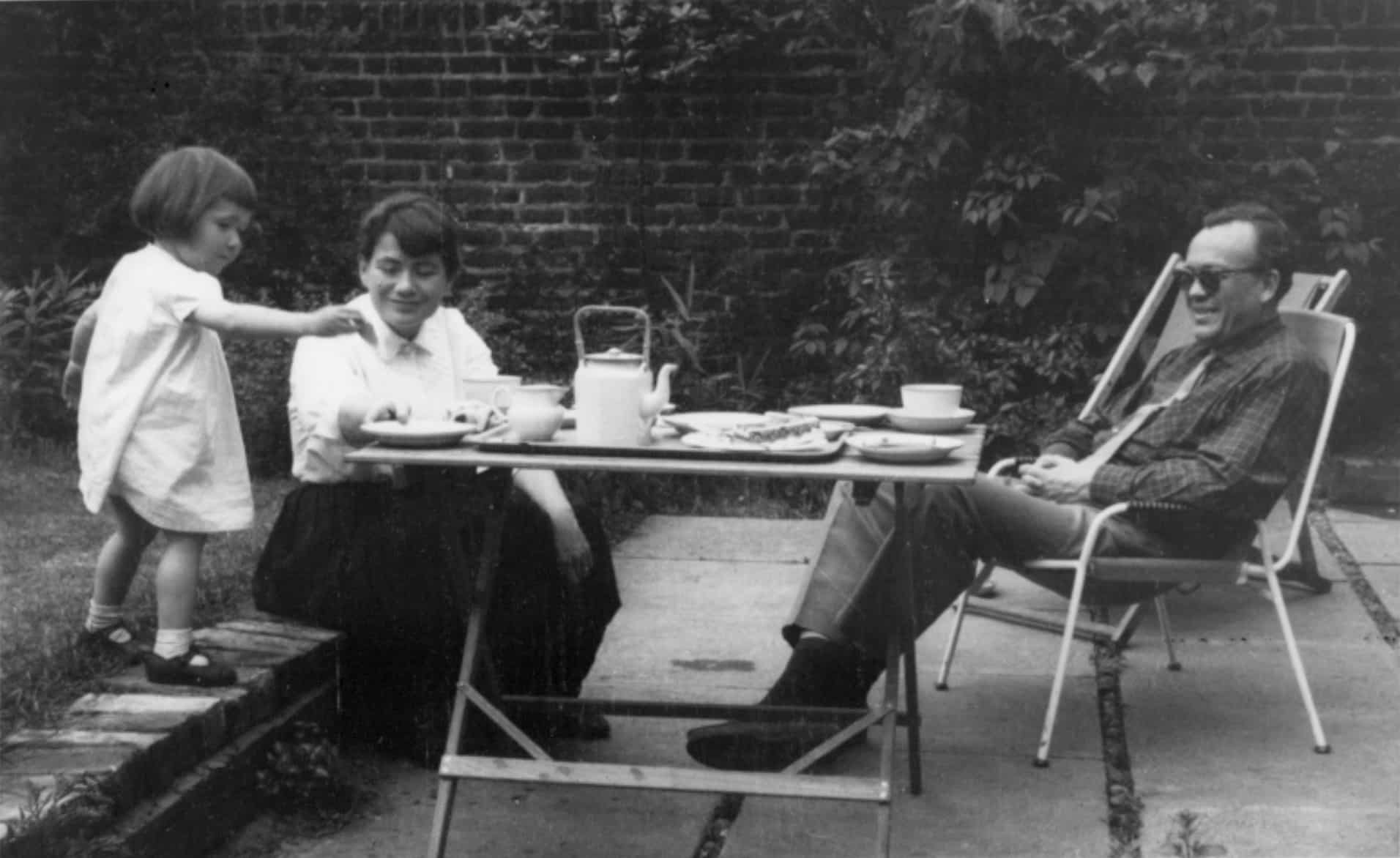

These had been left behind at the house in Islington which he had found and purchased with my mother in 1955, and on which he had done considerable work, converting it from a multi-occupancy slum dwelling into a pioneering exercise in restoration and improvement, predating the word ‘gentrification’, first coined in 1964, or indeed the term ‘Canonburyisation’, which never caught on. I had been born at home in this very house and it was where I saw my father always hard at work, when not at the office, in the distinctive studio extension that he added to the side of the building in 1980.

A decade later he had ‘hoofed off’ (my mother’s term), for bosky Peckham and his second wife, an inspirational demonstration of youthful energy at the age of 70, whilst leaving abundant proof of his previous life here; this included furniture he had personally designed, both fitted and free-standing, sections of his celebrated library, the occasional work of art from his even more celebrated collection, and hundreds of rolls of impossibly heavy architectural drawings. These had somehow all been stored up in the attic loft which he had carved out of the roof back in the ’70s, originally, ostensibly for my own use.

It took a great deal of effort and manpower to eventually move them down into the garage underneath my father’s office, the ground floor of his extension. Thus they went from one space designed by my father, at the very top of the house, to another, at the bottom, the side; from attic to garage, the two classic storerooms for those ambiguous things we cannot throw away yet never display, that we do not ‘know to be useful or believe to be beautiful’, doubtless there exists some poetic Japanese term for the spirit of ‘atticness’ and ‘garageism’.

To our delight Niall Hobhouse from Drawing Matter agreed to accept these drawings and generously had them all removed, ‘broom clean’, requiring vans and men and labour and strain, dust and sweat, the curious, paradoxical way that creative, imaginative ideas can eventually be translated, transmuted, into very heavy physical objects; even the writer of haiku leaves behind some groaning chest of treasures for their offspring to carry forward for the rest of their lives. The emptying of the garage, the departure of these drawings, seemed a symbolic final acknowledgement of the end of my father’s long career, his ceaseless writing and drawing and photographing, reading, and thinking, his death, I guess.

Yet my father is very much alive, alurking, throughout this house despite the ever-encroaching ever-growing stuff of myself and my mother who live there, the bare bones of his architectural presence, bannisters, cornices, remain a skeletal ‘ghost in the machine-for-living’. Thus, despite the fitting feminist-reversal of my mother the artist having entirely taken over my father’s monastic study with her own paintings, drawings, and etchings, I can easily imagine he is still hidden in there, with his cup of tea and T-square; for everywhere his aesthetic is resonantly present, imprinted into the faded hessian itself like some Shroud of Trevor.

I could not have been more pleased when Hobhouse revealed that he had discovered amongst his trove of Trevorania some of the original drawings for this house; even better he suggested we could try and match, echo, refract, my memories and observations of the house as it stands today with these drawings, my own anecdotal if not irreverent jottings contrasted with the precision, austerity even, of his beautiful pencil and ink, his initial limning of a lasting family house now dating back almost seventy years.