On Bramante (2022) – Review

– Oliver Lütjens and Thomas Padmanabhan

Thomas Padmanabhan: We are very happy to have this book, On Bramante, in front of us. It was written by a friend of ours, Pier Paolo Tamburelli, who is a writer, a teacher and also a practising architect and founding partner of baukuh in Milan.

For a while, even before encountering this book, I have been thinking about its precedents in Italy from the 1960s and 70s. These include the books of Bruno Zevi and Paolo Portoghesi on Renaissance and Baroque architecture, which are great publications. It is clear that they were trying to engage with the discourse of their time and seeking to influence contemporary architecture. In the case of Zevi this was embodied in his idea of organic architecture. For Portoghesi, it was the architecture of Art Nouveau, Borromini and the Baroque that he was presenting as relevant to contemporary architecture.

Oliver Luetjens: Yes, I see Pier Paolo’s book in a lineage with these publications too. However, this book is very different from those of Zevi and Portoghesi because, unlike them, in On Bramante he is not documenting the work of his subject, Bramante. Furthermore – and Pier Paolo states this clearly in his introduction – this is not a historical book. This is not a book about Bramante with a new historic value or new research; it is a theoretical work by a contemporary architect on Bramante.

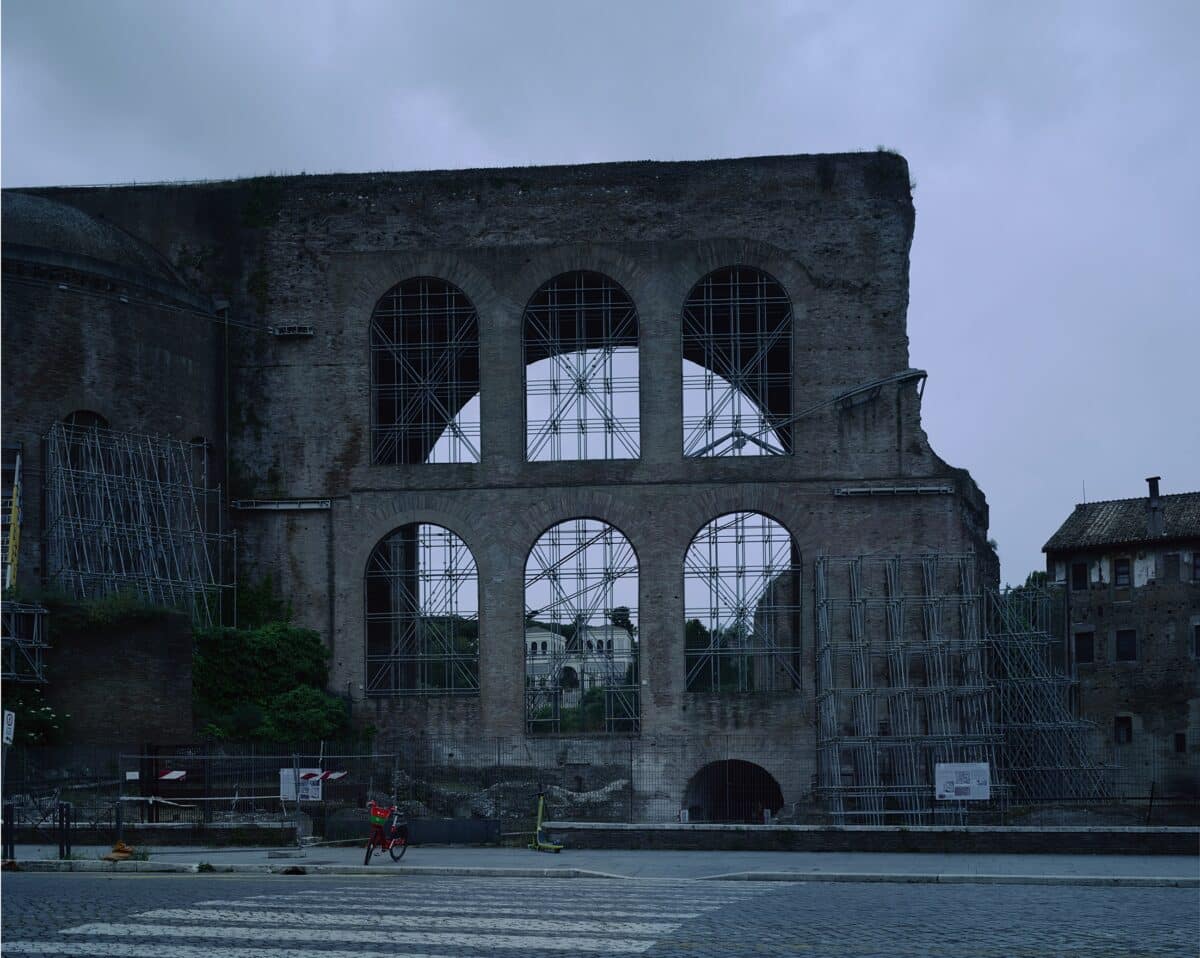

The text is structured as short and poignant chapters, which are organised into two parts separated by a central insert called Intermezzo. A photographic essay by the artist Bas Princen brackets the text, and each work is shown in one or two pictures. These photographs are not aiming at documenting Bramante’s built work, rather they appear as individual portraits that encapsulate a specific character of each work.

TP: In his book, Pier Paolo constructs an idea of Bramante’s architecture that is impersonal and universal. There is a distance with which Bramante operates, and Pier Paolo has empathy for Bramante’s distance. He also describes a certain coldness and flatness in Bramante’s work.

The key to this quality is the early Renaissance, when architects like Brunelleschi and Alberti were starting to reconstruct a language from Greek and Roman architecture – where they introduced the classical precedent. In the following generation, certainly in the case of Bramante but also Raphael, architectural elements became unified into what some people would see as a seamless system. This idea of a universal and impersonal architecture would later become the basis for classicism.

OL: Yes, but to me this book is not about the stylistic generalisations of classicism. It is not aiming towards the perfect system for architecture. What strikes me, is that this idea of the impersonal is tied to a personal feeling of awe. The awe that Bramante must have felt at his first encounter with the Roman ruins.

Pier Paolo describes the moment Bramante arrives in Rome. He sees the ruins, and the ruins are gigantic. But they are also part of the city – the contemporary city of Rome at the time. And Bramante realises that whatever he builds will be measured against these ruins. He experiences the sheer power of these structures, their impact, and in his vision, he sees their capacity to transform the city.

What Bramante found in Roman architecture was something incredibly energetic, an archaic force. This experience sets his ambition for a contemporary architecture. This is how Bramante becomes this incredibly bold architect.

TP: I agree with your reading, however, Bramante is clearly avoiding narrative in his architecture. He avoids anything that relates to the qualities of painting, and he is staying clear from any form of expressionism. For Bramante, architecture is mute. Architecture conveys an idea of background, generosity and context.

OL: Yes, Bramante might exclude narrative, but he is not devoid of the question of language. In the chapter ‘Architecture as Art’, Pier Paolo discusses the relationship of language and architecture. He describes architecture as an indirect form of art, an art that has its own content and maybe can provide a meaning but only as an artistic expression.

Spoken and written language can have a direct meaning, but architecture cannot have that direct meaning. Pier Paolo uses the example of a palace of justice to explain this. In this case architecture is incapable of prescribing what kind of justice will be done in the building. And even if the building was made with the best intentions, people could still behave cruelly and unjustly within it.

TP: Exactly, for Pier Paolo, Bramante’s architecture is about providing room for public space. Architecture is seen as a calm and stubborn background to life. Bramante’s architecture creates a stage for public life. This separation between architecture and life allows Pier Paolo to use Bramante as a witness for an architecture of autonomous form. Tacitly, he puts him in a lineage with Aldo Rossi and Giorgio Grassi.

He even cites Margaret Thatcher, who famously said there’s no such thing as society, only to disagree with her! For him, architecture provides the space for society to exist in the city.

OL: And therefore, Pier Paolo has so much optimism for the power of space – Bramante’s spectacle of space, as he puts it.

There is a paradox in Bramante’s work. His buildings have a specific programme, yet formally they are autonomous. The separation between function and form is one of the key ideas in the book. I think this is a strong and inspiring point he is making.

TP: Oliver, we know Pier Paolo as a practising architect. We cannot avoid reading his position on Bramante as a direct reflection of baukuh’s creative trajectory.

The continuous conversation we have been having with Pier Paolo and his partners over the past 15 years through and about our work is circling around the issue of the autonomy of architecture. Some of our recurring questions are: Does architecture exist in constant reaction to the things that happen in the world? Or does architecture express a laid-back generosity, a detachment, an autonomous discipline that needs to keep a distance from the chaos of life to exist? Or does architecture need or exist within both conditions – a kind of constantly moving, oscillating and tormented organism AND a self-sustained construct? In baukuh’s work, and to a lesser degree in Pier Paolo’s reading of Bramante, both tendencies strangely and beautifully coexist.

I am just wondering whether this position of saying that architecture creates a background while also saying that architecture exists mainly in its own realm, could be also an answer to the pressing question of sustainability. In the sense of working with limited resources and thinking how that could relate to the unexplainable relationship between function and form.

OL: Of course, if we build a building today, how can we be so sure about the longevity of its purpose and its function? Will these remain the same or change in the future? If architecture is more than a short-lived machine, isn’t autonomy the only way that architecture can relate to reality?

TP: There is another parallel between Pier Paolo’s view of Bramante and baukuh. Both deal with very powerful formal configurations. For instance, Bramante’s design for the St. Peter’s Basilica could be seen as an assembly of the Maxentius Basilica with the dome of the Pantheon on top. I think Pier Paolo proposes that Bramante’s design method involves a seamless montage. When Bramante combines the Maxentius Basilica with the dome of the Pantheon and the result is St. Peter’s, there is a continuous combination of both.

OL: Yes, I agree, and this really calls into question the idea of universality. For instance, baukuh could look at OMA’s Zeebrugge Terminal in the same way that Bramante saw a Roman ruin. Baukuh use the shape of the Terminal, and then add a portico by Schinkel to it. These are very specific and recognisable sources and baukuh are clearly enjoying the conflicts that appear within such a combination. It is bricolage. Existing things are put together to create a new unity.

TP: In the case of St. Peter’s, Pier Paolo puts it very clearly. Bramante took the Maxentius Basilica, and he puts the Pantheon dome on top of it; and then he has a project. Then Bramante starts to work on that project.

To me this is very fascinating. Bramante starts with a clear idea – a spatial idea that he is trying to resolve in space and as form. And he tries to find an adequate expression. Bramante eliminates a lot of questions at the beginning but then accumulates them, step by step.

OL: What I am missing in the book is a discussion on detail. Maybe that’s part of my thing when looking at architecture, believing that in certain details architecture reveals so much more about its condition than in the overall concept or in the general plan. In the book’s Intermezzo there is an intriguing discussion on the artistic sensibility shared by Dante, Giotto, Piero and Bramante. This sensibility reveals an intellectual distance and coldness that is in favour of a certain flatness of things.

However, looking at Bas Princen’s pictures I miss a detailed discussion on the pilaster in the corner of the cloister of Santa Maria de la Pace. This pilaster is so thinned out it’s almost disappearing. It is such a specific Bramante moment for me. I am also curious about the columns in S. Ambrogio in Milan. These are granite columns, like tree trunks with of branches sticking out and they have Corinthian capitals. They are so special because they are next to normal columns, and I do not recall having seen anything like this anywhere else. To me these moments speak about a different sensibility of Bramante – a sensibility with a soft spot for pathos.

TP: I hope this book, now that it is out, could open the discussion on a new generosity of architecture.

On Bramante is going to enter the English-speaking world – we are recording this conversation for the Drawing Matter website – it is going to address architects in the UK, but also internationally. In recent years, there has been tendency towards highly specific articulation in architecture. This book directs us back to a generous generic sense of beauty. It will be interesting to see how an English audience reacts to the idea that the generic and the generous could be as beautiful and as humanistic as the specific. I say this, because culturally, one could claim that the idea of a generic sense of beauty runs counter to an English artistic sensibility, where the truth can only be found – but perhaps I am exaggerating – in the specific.

Pier Paolo Tamburelli On Bramante (2022) is published by MIT Press. Copies of the book can be purchased here.

Oliver Lütjens and Thomas Padmanabhan of Lütjens Padmanabhan Architekten currently run a studio at Harvard University Graduate School of Design.