The Religious Architecture of Alvar, Aino and Elissa Aalto (2023) — Review

There is an ongoing debate within the field of theology and the arts concerning to what degree ‘theology’ must guide the discussion. Those on one side of the divide argue that unless the terms are clearly staked out within traditional discourses and literature in theology, we do not know what is being talked about by such a relationship. On the other stand those who proclaim that, for the typical person walking down the street, there is no such thing as a clearly defined theology—there are only those glimpses of meaning that suddenly appear in unexpected experiences of everyday life, make an impression, and dissipate as quickly as they came.

The more specialised discipline of theology and architecture stands within the field of theology and the arts, bearing the weight of this debate all the same. While many perceive the relationship as one concerned with prescriptions on ecclesial designs, on formulas for making a ‘church look like a church,’ the more recent voices in the discipline are emphasising that the importance of theology for architecture is in cutting through functionalist tendencies to seeing that ‘architecture is a poetic activity.’[1] Architecture builds out of necessity, but it creates for the sake of what is not necessary. In doing so, architecture defines space and helps to make possible the very experience of place. It creates the meaning of place.

As with all interdisciplinary endeavours, theology and architecture partially grounds its legitimacy through interaction with architectural studies. When it comes to the monumental temples of the ancient world, the haunted basilicas of the classical period, the fanciful Medieval cathedrals, or the innovations during the Renaissance, this exchange is rather straightforward. Religion is accepted as a historical fact, and the conversation is at most to what are the specific contours of such religions and the sacred structures. When it comes to the modern period, however, things are much more tenuous.

Sofia Singler has put forth an important contribution to these various discourses and fields with The Religious Architecture of Alvar, Aino and Elissa Aalto. Her argument tempers both sides of the theology and architecture conversation. To the latter, she develops a substantial case for religion as a constitutive factor in Aalto’s designs and built works; to the former, she does so in such a way that will cause theologians to hesitate before claiming Aalto as another of their own.

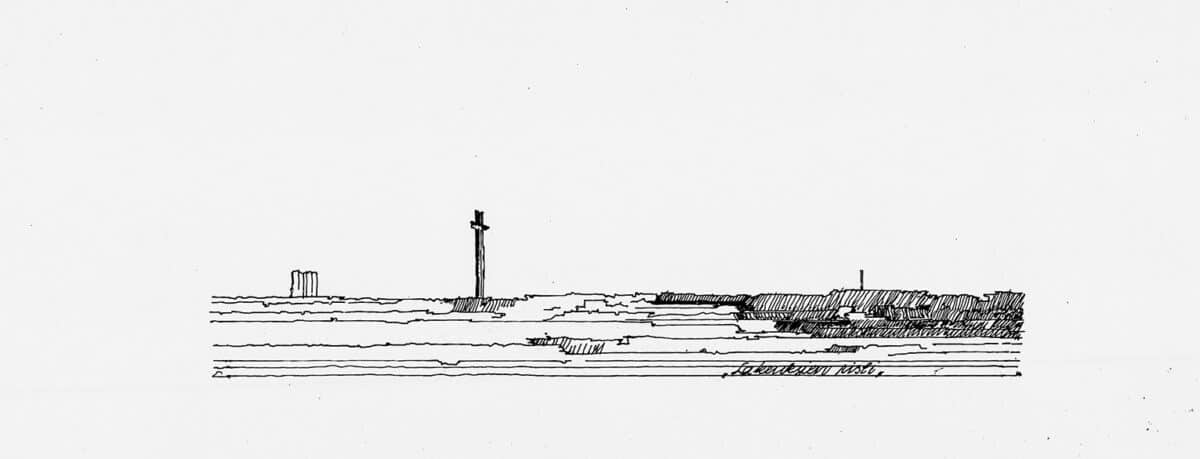

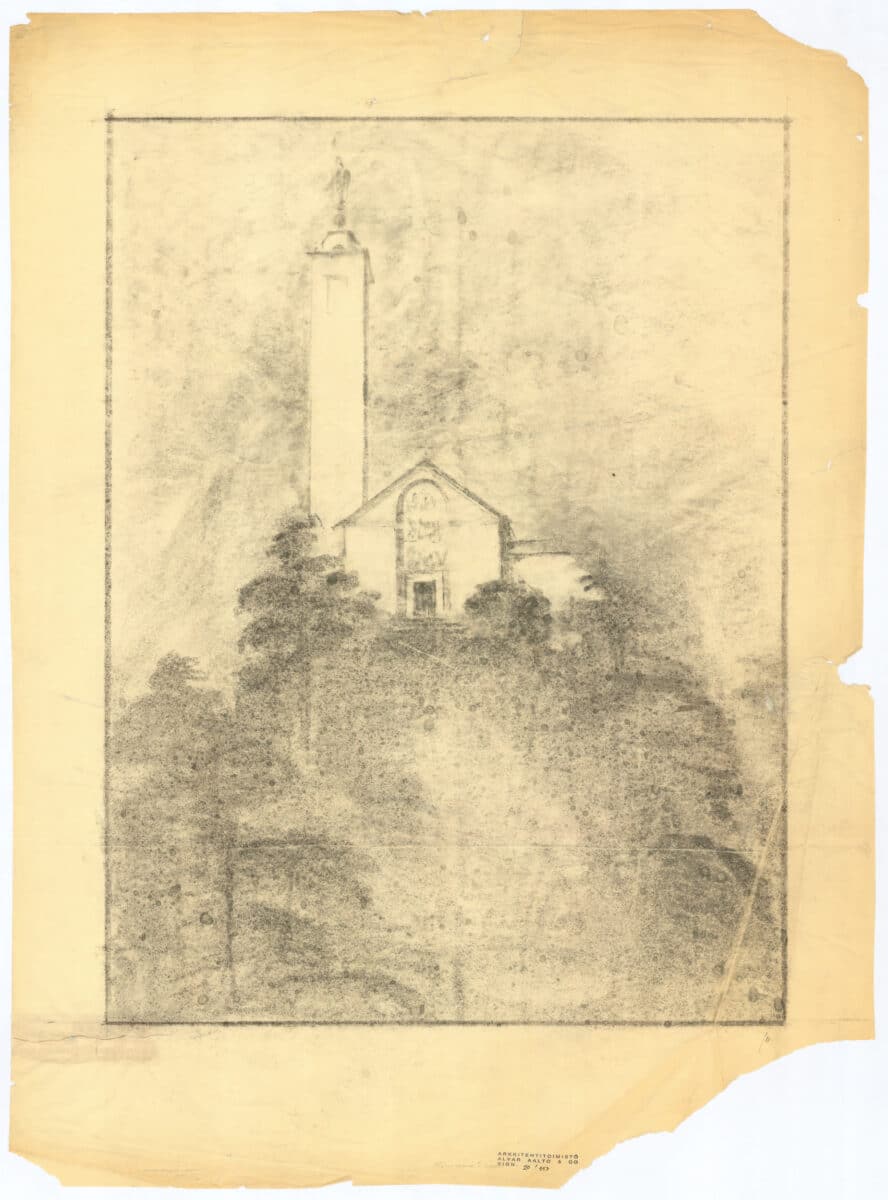

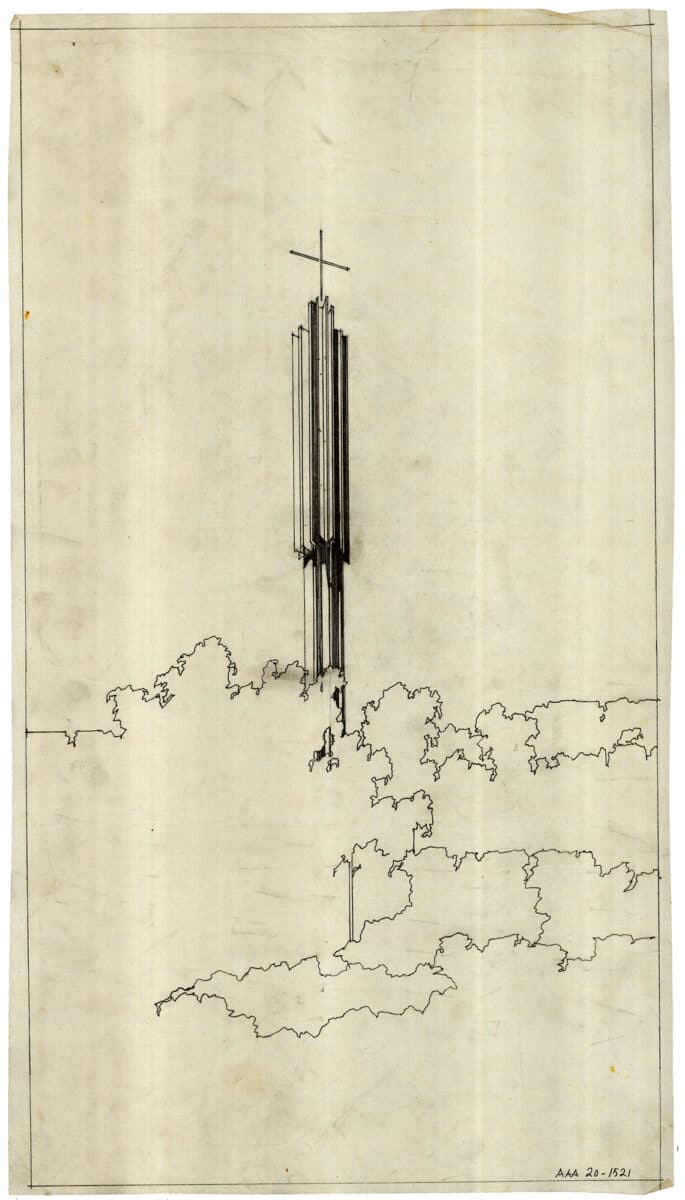

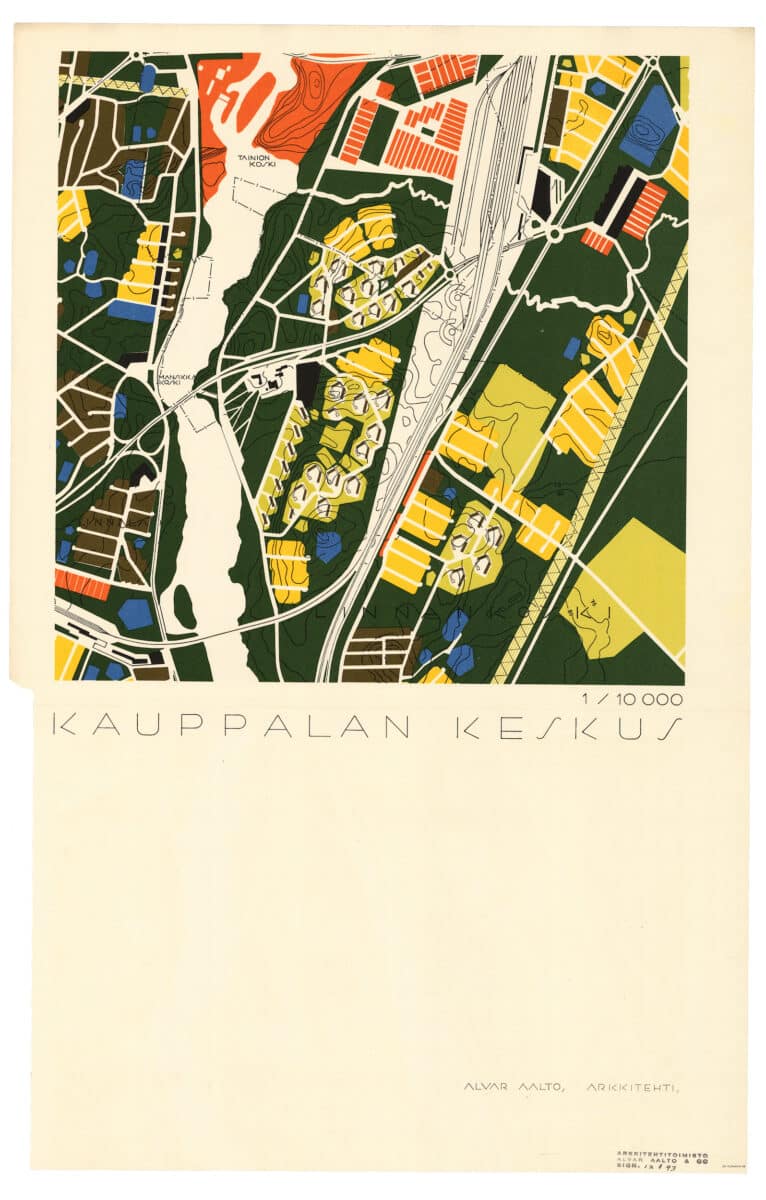

Several relevant works come to mind which have achieved similar feats in the past. From the side of artistic literature, Aalto takes a place alongside such discourse-shifting works as James Elkins’ The Strange Place of Religion in Modern Art (2003), Charlene Spretnak’s The Spiritual Dynamic in Modern Art (2014), and Thomas Crow’s No Idols of Art: The Missing Theology (2017). From the theological side, it adds an important voice to the conversation begun by Michel de Certeau’s Walking in the City (1980), continued by Graham Ward’s Cities of God (2000), and Murray Rae’s Architecture and Theology: The Art of Place (2017) which introduces Finland’s most famous architect to the young discipline. Additionally, Singler works through previously untouched material in the archives at the Alvar Aalto Museum, as well as beautifully illustrating the pages with various photos and numerous sketches of Aalto’s design process, making it a significant contribution to Aalto’s studies on content alone.

Singler’s argument in Aalto is that religion is just as noteworthy a facet of Aalto’s modernism as are architectural trends, technology, economic, politics, and geography. In fact, given that Aalto engaged with some three dozen religious projects that span the length of his career, one of the biggest puzzles of secondary literature is the motivation behind such a large ecclesial oeuvre. These designs are typically explained away as opportunistic instances to play with new ideas, as Singler notes [2]. However, there are a substantial number of details which simply do not fit easily into the common reading. Singler works from these outliers to construct an intriguing theory of the religious intimations and tendencies of Aalto’s design.

The primary obstacle for Singler to overcome is the rather clear lack of personal faith in Aalto’s biography. Singler clarifies that her argument does not pertain to the convictions of Aalto, but only to display how the ‘religious and theological discourses’ of his context influenced his ecclesial projects [3]. Within these discourses were several shared concerns between Aalto and his religious clients that helped to ally against tendencies developed in the wider context of building, city planning, and design. Thus, it is not so much that Aalto is championing a religious position as much as he is consciously engaging in religion for the sake of his architecture. Yet, in doing so, he finds himself growing sympathetic to the depth of meaning upon which the church stands—a foundation which he builds upon even outside his explicitly religious designs.

Singler concentrates on eight of Aalto’s completed projects: The Church of Muurame (1926-9); The Church of St Stephen in Wolfsburg (1965-8); Church of the Three Crosses in Imatra (1955-8); The Alajärvi Parish Centre (1966-70); Cross of the Plains in Seinäjoki (1958-60); Church of the Cross in Lahti (1975-9); Church of the Holy Ghost again in Wolfsburg (1960-62); and Church of St Mary the Assumption in Riola di Vergato (1975-80). All but three of these projects are located in Finland, the context that Singler uses to establish the basic tenants of her overall argument. When she turns to the churches in Germany and Italy, she shows that similar religious impulses are also in operation, at least implying that Aalto has taken something from the Finnish projects through which he is interpreting his tasks and responsibilities more widely.

The book is structured along two different trajectories. The first is in the chapter topics, which approaches the general argument from a unique perspective. The first full chapter after the introduction, ‘Building Country and Community,’ paints a narrative of how shifting geo-political boundaries between Finland and the USSR after WWII produced the need for a unification of several townships and their associated ecclesial dioceses. The resulting project—Cross of the Plains—indicates direct influence from the religious voices involved in such matters. These voices were spurred on themselves, however, by concerns about reinstating the church’s need and presence in an increasingly secular context. This discussion is continued in a similar vein in chapter three, ‘The City and The Sacred,’ highlighting the association between nature and religion in the Finnish social imaginary. These two consolidate against a push towards industrialisation and technological advancement of society, further complicating any clear division between secular and sacred motivations of Aalto’s relevant projects. Singler also shows that Aalto’s post-war work in Germany and Italy comes to form in a similar fashion. This sort of toeing the line from both sides is one of the more elegant features of Singler’s presentation.

The next three chapters discuss Aalto’s idiosyncratic style in terms of modernist designs, attempting to mark out the distinct role religion plays in his influences. The core of chapter four, ‘Making a Modern Church,’ is an interpretation of Aalto’s monumentality as a critique against both ‘modernism as a style or movement’ and the secularisation mission it often brought with it [4]. This claim is augmented by a discussion of Aalto’s stance towards functionalism which, as Singler explains, shifts following a series of rejections for church buildings in the 1930s. While not wholly rejecting the imperative of designing a ‘church that looks like a church,’ Aalto enfolds a ‘sense of mystery’ within his modernistic tendencies [5]. The result was the Church of Three Crosses, which is likely Aalto’s ecclesial masterpiece, and reveals his tendency to draw on more traditional architectural ideas than his contemporaries. In a parallel discussion, chapter six makes the much stronger claim that Aalto was drawn to religion not only as a common enemy to the wider cultural movements, but specifically to a ‘more traditionally Christian understanding of religion’[6]. Chapter five, ‘Resisting Reform,’ is the most relevant portion of the book for theology and architecture. Here, Singler compares the interior organisation of Aalto’s churches to that of his contemporaries, such as Le Corbusier. What she details is that Aalto took special care with the placement and detailing of the altar, pulpit, and organ in each project, which are three elements particularly predominant in Lutheran theology. The discussion shows how Aalto’s sensibilities to acoustics and sonic performance played a key part in the overall design, making this one of the more interesting sections of the book. The chapter ends with a sustained analysis of Aalto’s use of the cross, both as a monumental symbol and architectural shape, which aligns with the Lutheran message of the sufficiency of grace over works in faith.

In chapter seven, Singler takes to task the common interpretation that Aalto’s seemingly religious sensibilities are a resonant echo with the German Romantics, as set forth by Sigfried Gideon. She takes note of a significant number of ecclesial voices involved in Aalto’s projects—either as clients or colleagues—and the degree to which they appear to steer his decisions. This fills in an important gap in Singler’s position and helps to double down on her claim that Aalto’s religious impulse cannot be reduced to a vague notion of postmodern spirituality. The final chapter, ‘The Gift of Doubt,’ punctuates this claim by asserting that Aalto’s choice to engage with ecclesial projects was seen as ‘opportunities to deepen and further develop’ his critical stance on the modern situation [7].

The second trajectory that runs through Aalto takes its form through several key themes which support the claims of the argument. The more architecturally related of these include: issues of increasing industrialisation and the ‘forested character’ of Finnish communities [8]; the related question of the location of churches in relation to urban density and city planning [9]; the physical delimitation of inside-outside in the design itself [10]; and the pressing concern of secularisation of religious space in modernism [11]. For more theologically oriented themes, Singler discusses: the important influence of Aalto’s personal relationship with Bishop Simojoki [12]; the presence of biblical passages in Aalto’s notes and conversations [13]; the architect’s attention to sacred spacing [14]; his liturgical concerns [15]; and his explicit resistance to pantheistic ideas, which would include the description of his ecclesial works as engaged in a postmodern spiritually [16].

These themes typically appear in each chapter, showing how the various topics add something to the weight of the chapters’ claims. They effectively detail how religion deepens Aalto’s design. The recurring use of these themes does tend to make the argument repetitive, which is perhaps the strongest criticism of the book. The writing is also dense, at times losing the thread of the argument or topic. But these slight faults do not outweigh the value of the project.

Sofia Singler, The Religious Architecture of Alvar, Aino and Elissa Aalto (2023) is published by Lund Humphries. Copies of the book can be purchased here.

Charles Howell is a PhD student in Theological Aesthetics at the School of Divinity, University of St Andrews.

Notes

- Murray A. Rae, Architecture and Theology. The Art of Place (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2017), 2.

- Sofia Singler, The Religious Architecture of Alvar, Aino and Elissa Aalto (London: Lund Humphries, 2023), 6.

- Ibid., 8.

- Ibid., 61.

- Ibid., 69.

- Ibid., 156.

- Ibid., 182.

- Ibid., 16; 34-43;130-8.

- Ibid., 54-60; 80-9.

- Ibid., 59-60; 190-9.

- Ibid., 61-9; 182-90.

- Ibid.,18;189; 97; 203.

- Ibid., 27; 75;125-9.

- Ibid., 89;162.

- Ibid., 109-18; 59-60.

- Ibid., 144-56.