Banham in Buffalo

[Our] main emphasis in this course has been on using primary sources in studying architectural history. By this I mean that we have been using the building itself as the first source of information about the history of the building.[1]

Reyner Banham moved to America in 1976 to take up an appointment as Professor of Architecture at The State University of New York in Buffalo. Located on Lake Erie, the city has direct connections to North America’s Midwest and the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 forged links to the eastern seaboard that brought new industries and increased prosperity. Shipping, railways, and the storage of grain were supplemented by steel making, car building, and food processing, and, with plentiful supplies of electricity generated nearby at Niagara Falls, the city prospered. By 1901 Buffalo’s population included more millionaires per capita than any other American city and those wealthy citizens sought out notable architects, engineers, urban planners, landscape designers, and craftsmen to create a city that was planned around impressive infrastructure and signed by significant buildings.

On his arrival in Buffalo, Banham found a place that had declined economically yet remained architecturally intact. It was, he suggested, ‘a fossil industrial city where nothing much had happened since the 1930s’.[2] That city, its history, people and buildings were to significantly shape Banham’s teaching and research.

With encouragement and support from the Buffalo Architectural Guidebook Corporation, Reyner and Mary Banham worked together to study the place and Buffalo Architecture: A Guide, a comprehensive view of the city, was published by MIT Press in 1981. It traced the development of the city and recorded notable buildings: landmarks designed by Louis Sullivan, Daniel Burnham, H.H. Richardson, Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Upjohn, Eliel and Eero Saarinen, Albert Kahn, Raymond Loewy, Minoru Yamasaki, Paul Rudolph and Gordon Bunshaft, located within the radial city plan devised by Joseph Ellicott and networks of parks and parkways designed by Frederick Law Olmsted.

The book, an invaluable reference for architects, residents, students, and those with an interest in architecture and cities, also included contributions by Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Charles Beveridge. Banham’s introduction noted: ‘This book is intended to make it impossible, ever again, for anyone who cares about architecture to say, “We drove to Buffalo on the Thruway, but decided not to stop because there’s nothing there to look at—is there?’[3]

Banham taught courses in architectural history and design at the State University of New York at Buffalo that focused on the city. He initiated ‘field studies’—a format that required students to leave campus, examine local buildings, draw, write and document what they saw as a basis for learning.

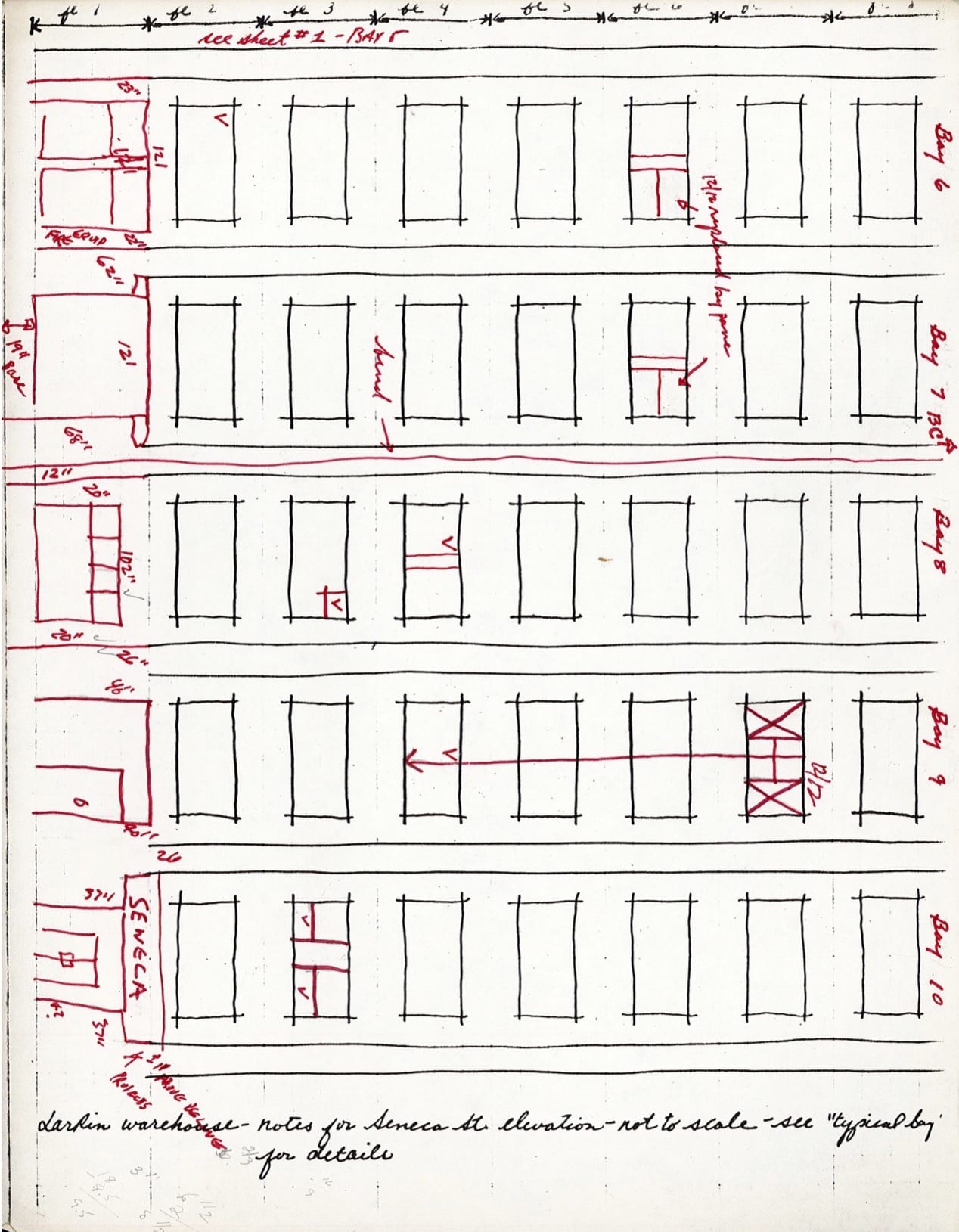

The Larkin Company was a popular destination. Established in 1875 to make soap, the company prospered, moved from modest premises, and developed a complex of buildings on Seneca Street where its proximity to an extensive network of rail lines facilitated a transformation into a mail order conglomerate. By 1920 the Larkin Company employed more than 2000 people, distributing products across the continent and had an annual turnover of $28.6 million.

Frank Lloyd Wright had been commissioned by Darwin Martin, the Corporate Secretary, to design a new Administration Building for the Larkin Company in 1904; it was a tiny block in a vast industrial complex and was demolished in 1950, yet it is a building that continues to inspire.

When Banham went to Seneca Street with his students, he encouraged them to look closely at the industrial warehouses, as well as remnants nearby, and their close examinations revealed how changing uses, ingenuity, and time shapes architecture.

Simultaneously, Banham pursued his own research with ‘field studies’ focused on grain elevators, warehouses, and daylight factories. They revealed links that connected modernism in the Americas to the preoccupations of contemporary architects in Europe. That research prompted the publication of A Concrete Atlantis: U.S. Industrial Building and European Modern Architecture by MIT Press in 1986—a book that traced links connecting Buffalo with European Modernism and which concluded with a chapter entitled ‘Modernism and Americanism’.

Notes

- Letter 20 July 1977 from Linda Sichel to Reyner Banham. University at Buffalo, Special Collections 44/5/1133 BOX 1 Buffalo: The industrial heritage, course records.

- ‘Larkin and Buffalo’, lecture by Reyner Banham at ACA, 1982

- Reyner Banham et al, Buffalo Architecture: A Guide (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1981), 1.

Brian Carter is a registered architect and Professor of Architecture at the University at Buffalo. The School of Architecture and Planning at the University at Buffalo awards an annual Banham Fellowship to emerging designers and scholars.