Alternative Histories: Bardakhanova Champkins on Virgilio Marchi

Had the Zuev Worker’s Club competition (Moscow, 1926) been won by Konstantine Melnikov, and not resulted in the well-known building by Ilya Golosov, perhaps a different strand of rationalism would have emerged in pre-war Italy. This could have extended the earlier speculations of Futurists such as Virgilio Marchi; Terragni’s NovoComum housing might have been quite different.

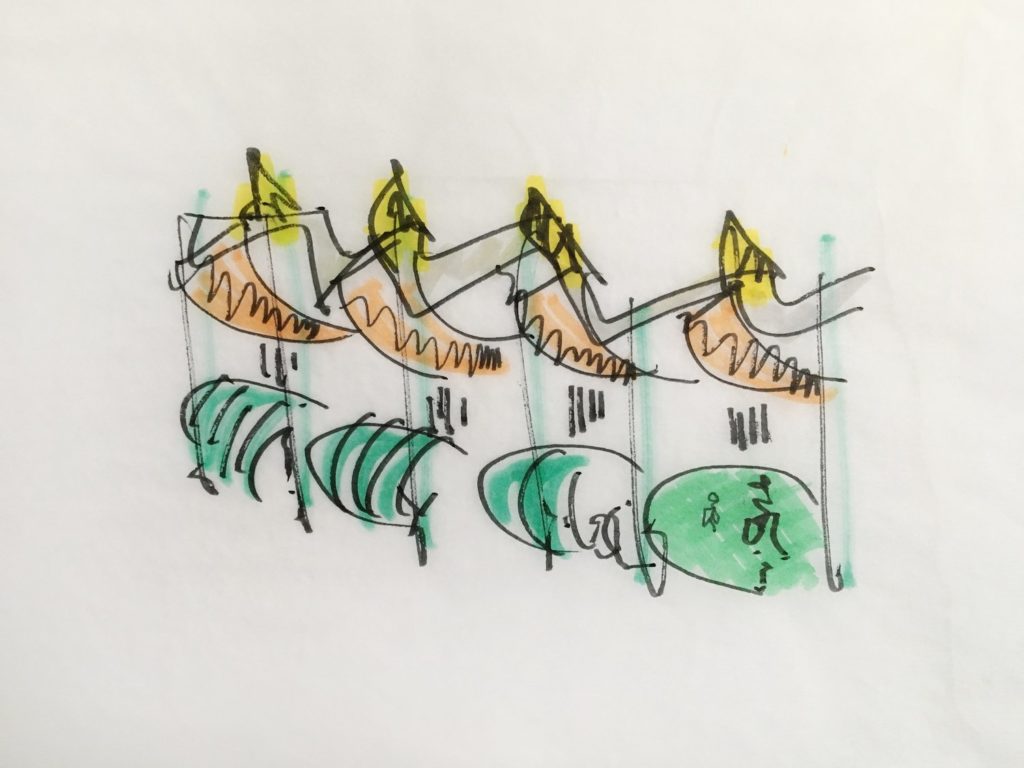

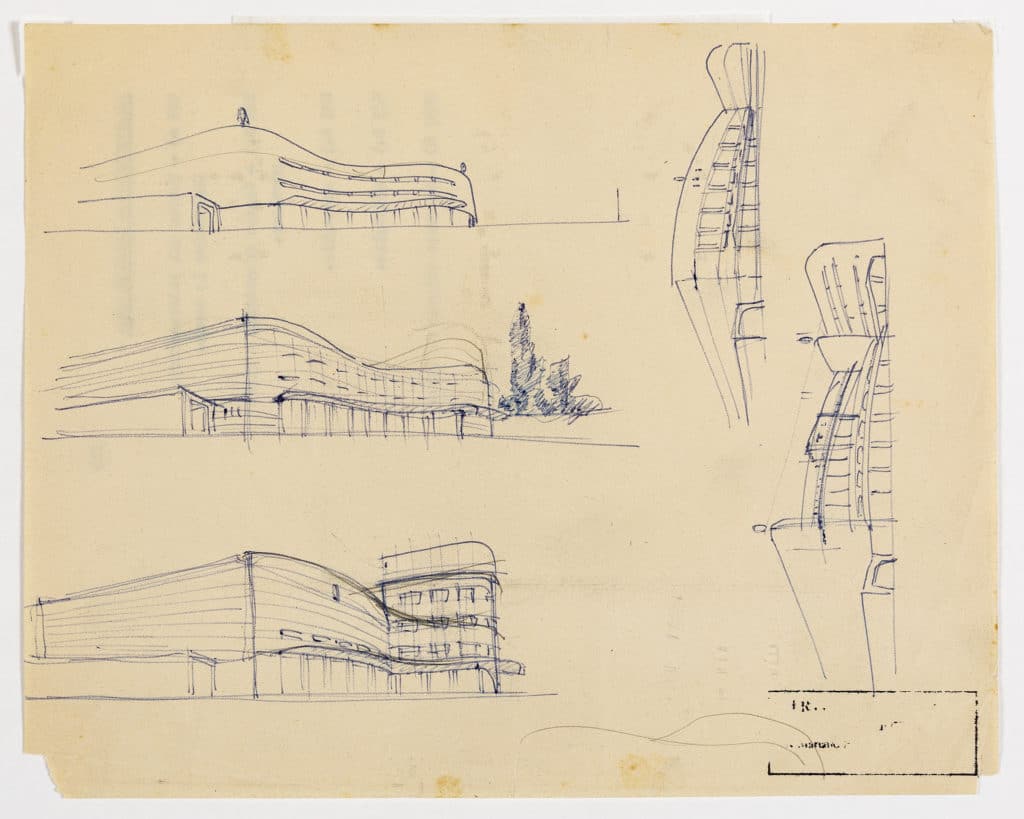

In Marchi’s drawing for the Odeon Cinema (1940) we recognise the beginnings of a certain anxiety and retrenchment of ambition that is also evident in contemporaneous buildings in Russia, a decade after Golosov’s Zuev and Melnikov’s Rusakov Worker’s Clubs. We see almost a retreat from, and loss of confidence in, the agency found in spatial, volumetric and organisational vigour that characterised Marchi’s work of the early 1930s. The later drawings are polite, mannered and more conventional compositions, furnished with academic styling; analogues for each approach illustrated can be identified across Europe.

Externally the cinema as-built (1952), with a compact plan and simple two-storey massing, took this initial trepidation to a logical conclusion and is quite unlike the sense of ambition, even if somewhat neutered, that is captured in the drawing. Moreover, none of the breathtaking sculptural and spatial dexterity that defined his early, more explicitly Futurist proposals, is manifest – no doubt reflecting the radically changed political and economic context of post-war Italy.

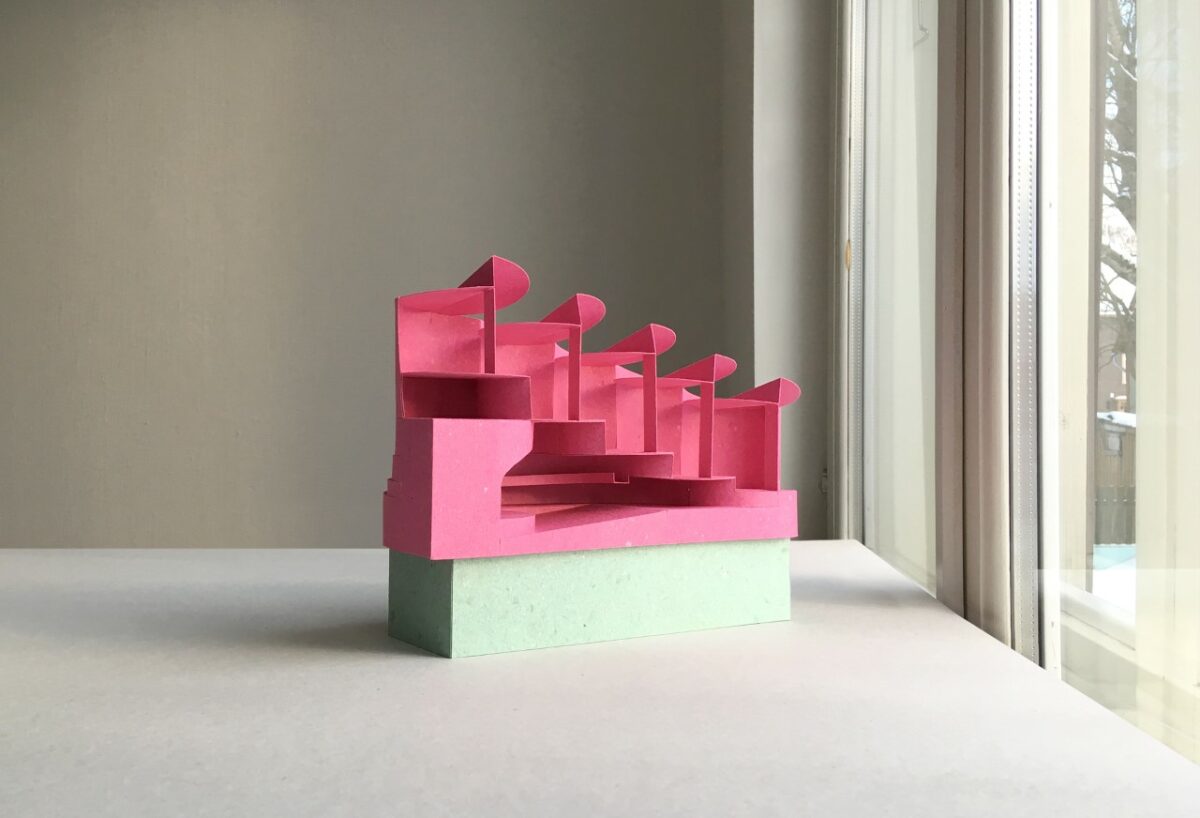

Though few photographs of the cinema exist, it is clear that Marchi placed his emphasis on the spatial and expressive qualities of the internal volumes. From the two-storey elliptical and colonnaded entrance hall with a deceptive perspective, flanked by the ticket offices, bar and two sweeping staircases, cinema-goers were led via a horseshoe-shaped corridor to the main hall. Originally with 2,500 seats, the cinema hall was a subtly organic trapezoid in plan balanced by exuberant cantilevered and parabolic gallery floor. This forms the first element of ‘slipped’ ceiling terminated by a generous exedra, within which the stage and screen are placed. The parti is formed by several carefully controlled and intersecting circular and sinuous geometries that are celebrated and articulated by the expressive use of ribbons of light as a surface. This was a wonderful space, quite unlike our contemporary mono-functional and self-centric cinema ‘experience’.

– Irina Bardakhanova and Nicholas Champkins