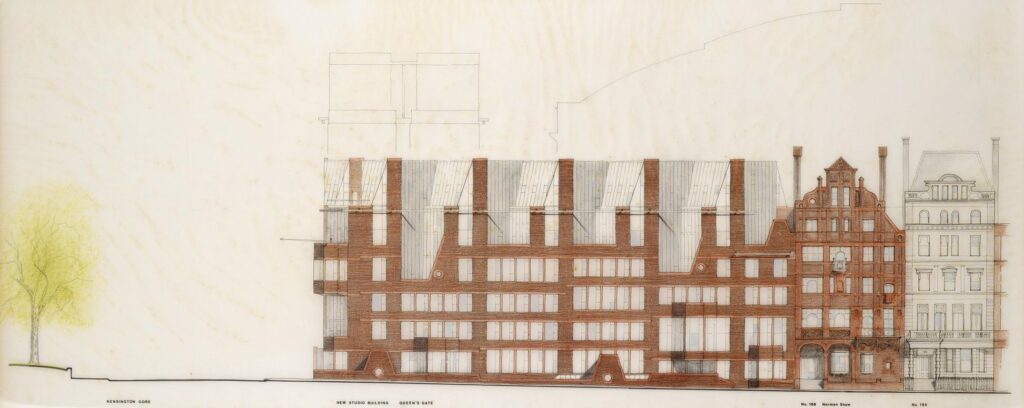

Alternative Histories: Stephen Bates on Henry Thomas Cadbury-Brown

Reading Jim Cadbury-Brown’s transcript of ‘Ideas of Disorder’ delivered at the Architectural Association in 1959, it is clear just how far he had moved from his functionalist modern movement origins towards a more expressive and instinctive idea of what architecture could be and mean.

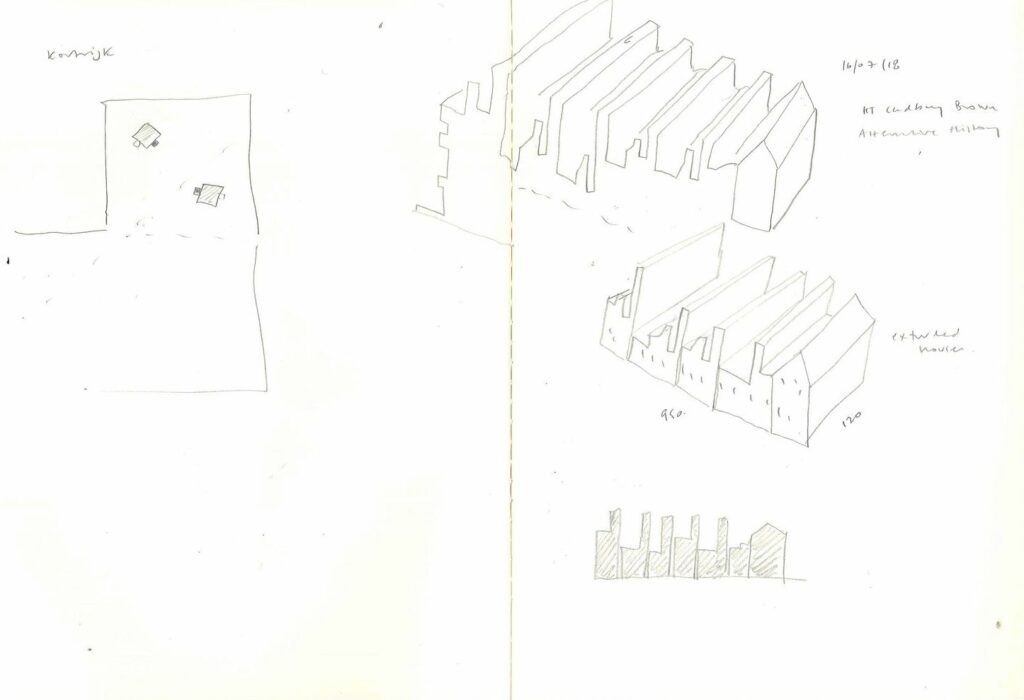

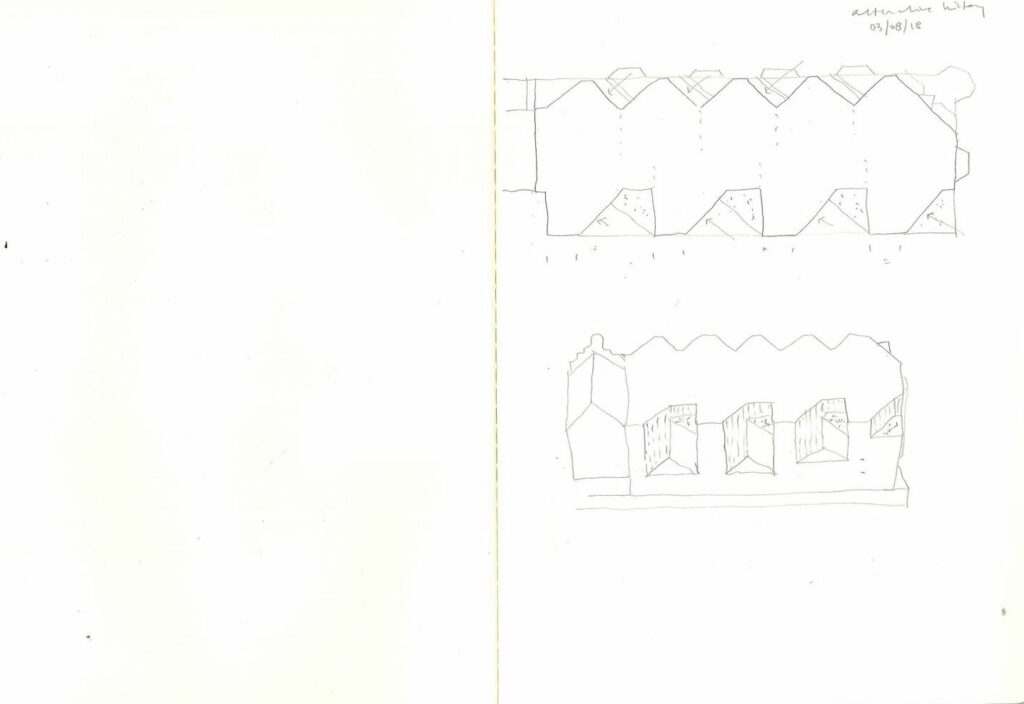

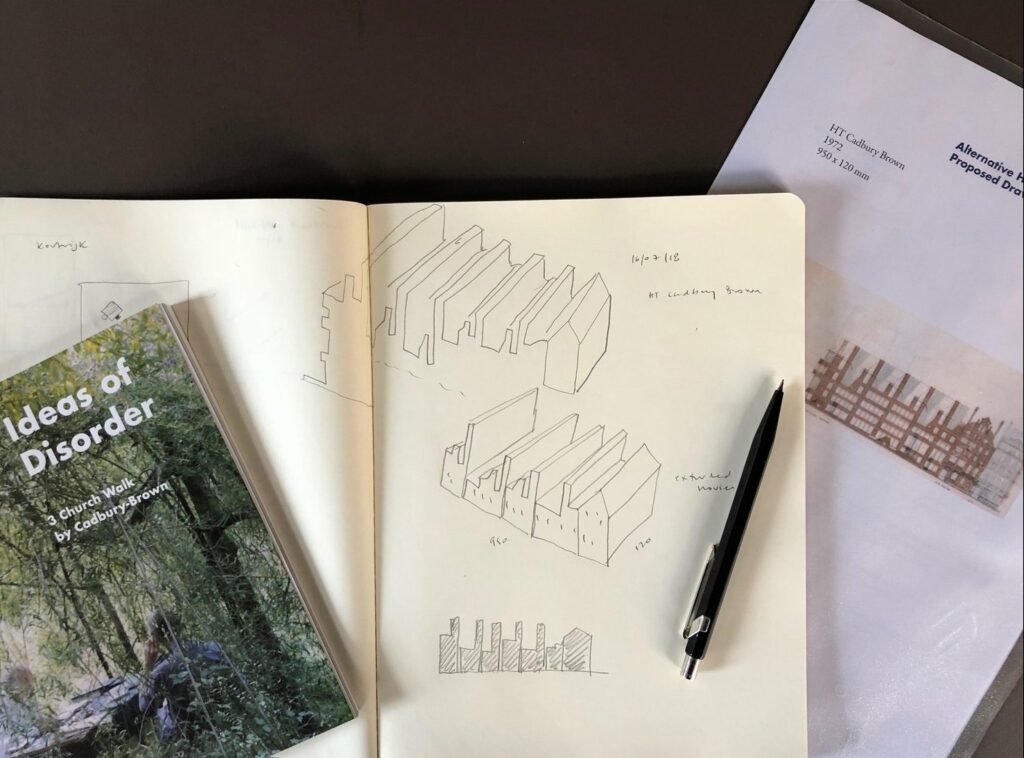

The drawing of a first scheme for the Royal College of Art on Queen’s Gate, just around the corner from the building he finally built in collaboration with Sir Hugh Casson, is a remarkable blend of semi-industrial and muscular forms. It has a frame-like tectonic whose scale and order seem to emerge from a careful reading of Richard Norman Shaw’s adjacent 196 Queen’s Gate. The vertical and highly articulated large-scale villas that characterise the street on both sides are referenced within the syncopated rhythm of brick piers that seem reminiscent of chimneys. This led me at first to see the project as a series of extruded elements. But later, after more careful observation and some attempts at sketching the consequent modelling of the volume with only lines and shadows, I realised that Cadbury-Brown’s intention was to make a more autonomous form, rich in specific moments.

My task was to continue and complete the project, giving form to the gable elevation facing Kensington Gore and the rear elevation inside the block behind Jay Mews. The folded metal roofs and large glazed elements evoke studios and workspaces for which I defined a suitable rear elevation, continuing the articulations of folds and cuts within the building volume. Cadbury Brown’s intention seems to have been to propose a red brick architecture with modern industrial materials and details that pre-date Stirling and Gowan’s early work in Leicester and Cambridge. The building would have stood as a statement of resistance to the decorum of Queen’s Gate’s mid-Victorian villa architecture. I continued and finished the work by slightly editing the front elevation and presenting the whole in a single material – plaster – hinting at its potential as a single conglomerate rather than an assemblage of separately articulated elements.

– Stephen Bates, February 2019