Christoph Schlingensiefs Operndorf Afrika (2020): Review

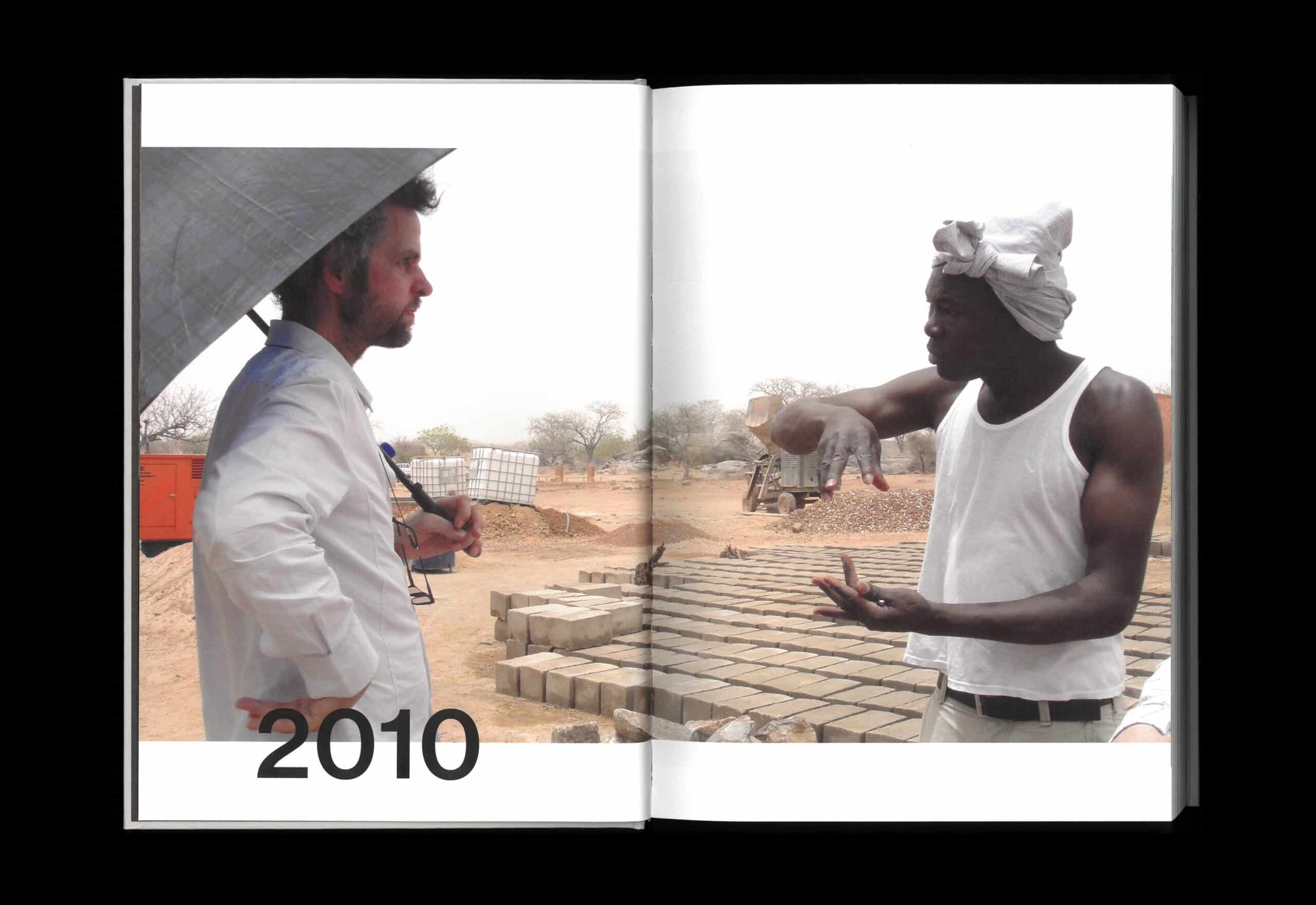

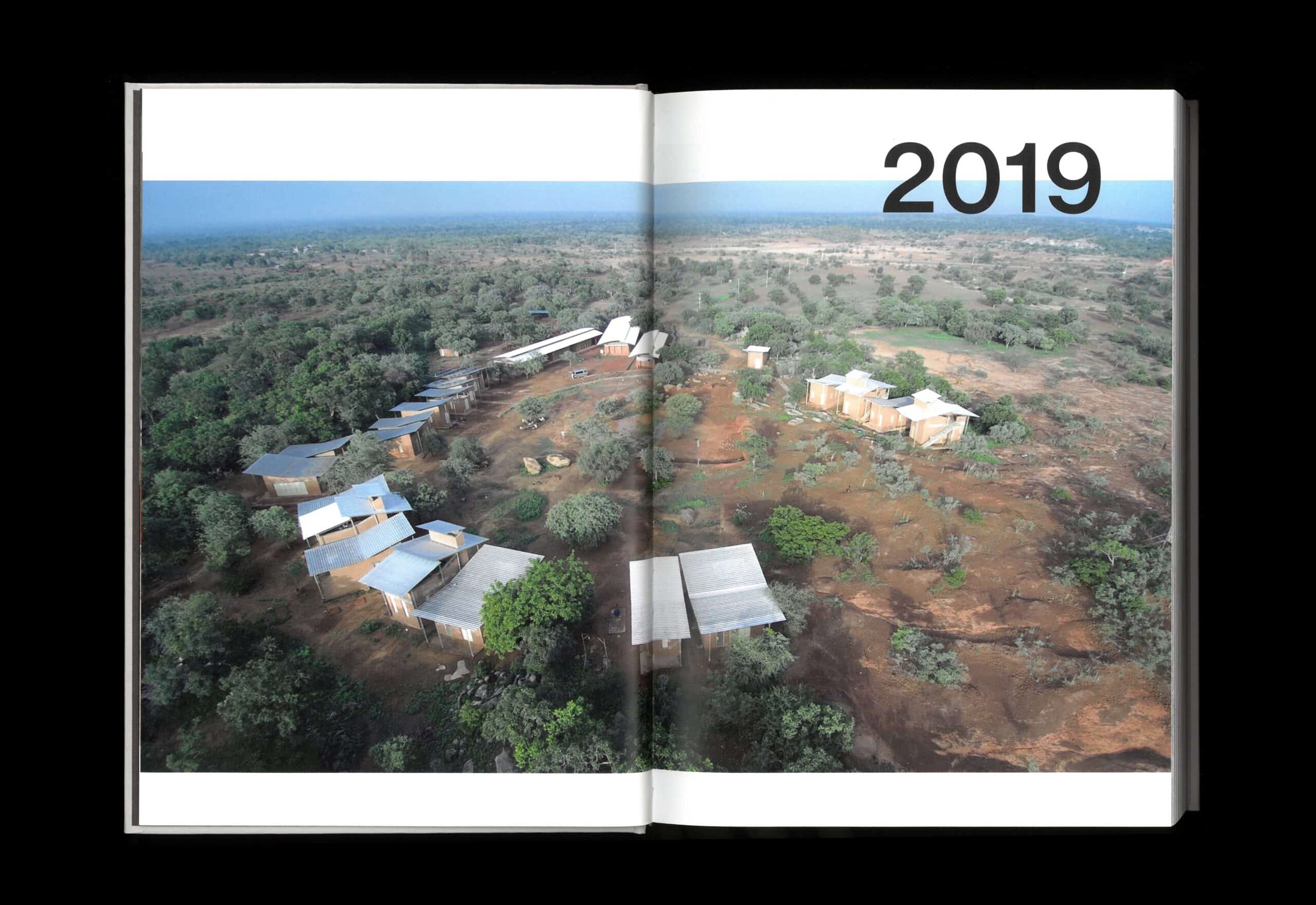

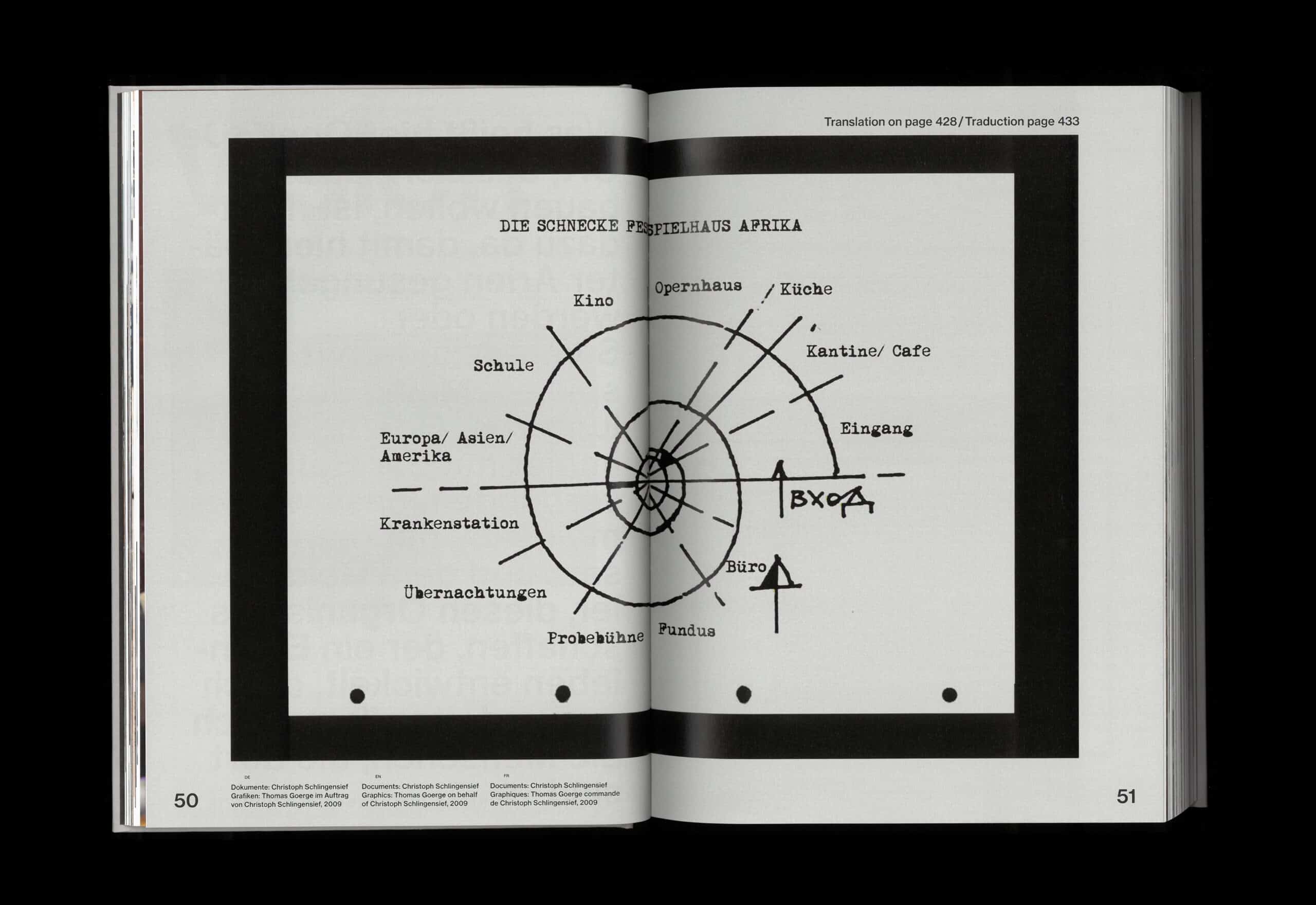

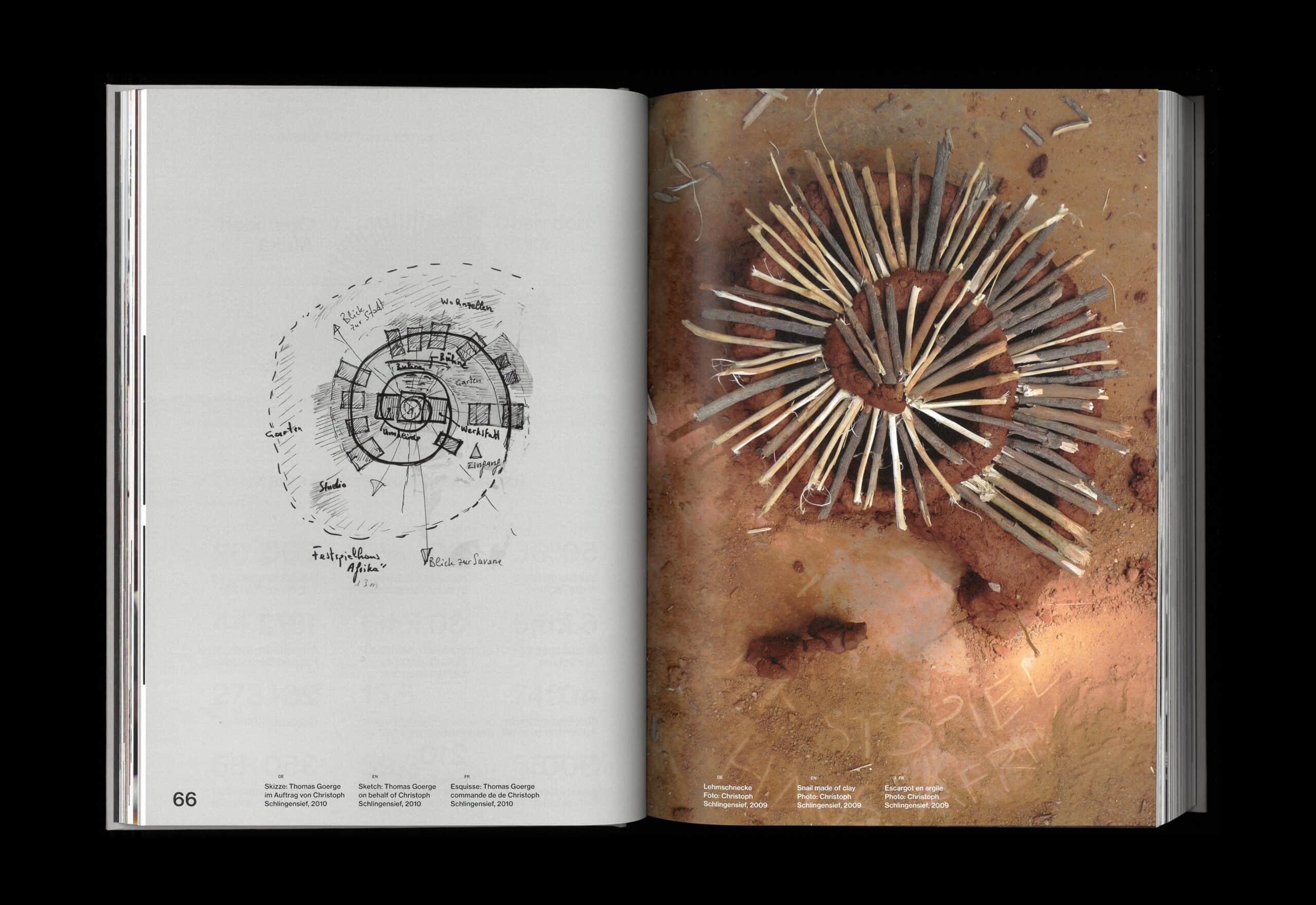

The Opera Village is a complex located thirty kilometres from the capital of Burkina Faso that was initiated by the late German film, theatre, and opera director, author, and action artist, Christoph Schlingensief and envisioned as a site centring African artists and enabling cross-cultural creative exchange. The ever-expanding project combines a school with an arts-based primary education, arts programming (which includes an intra-African art exchange), and healthcare facilities. The earthen complex is designed by the Berlin-based Burkinabé architect Diébédo Francis Kéré, with the initial foundation stone having been laid in 2010. Christoph Schlingensiefs Operndorf Afrika is a recent hardcover publication by German publisher Spector Books that gathers photographs, interviews, speeches, correspondence, as well as architectural documentation, to tell the story of the first decade of this project. This book is edited by Aino Laberenz who is Chair of the Operndorf Afrika Foundation and a managing partner of the non-profit that oversees the project (Festspielhaus Afrika gGmbH). Mario Lombardo and his team, who have been responsible for the corporate identity of the Opera Village since 2014, are the designers of the book. Operndorf Afrika’s content is presented in a relaxed manner, with minimal hierarchy, easing the reader into the subject and providing a holistic understanding of this work, from a variety of perspectives, including the everyday.

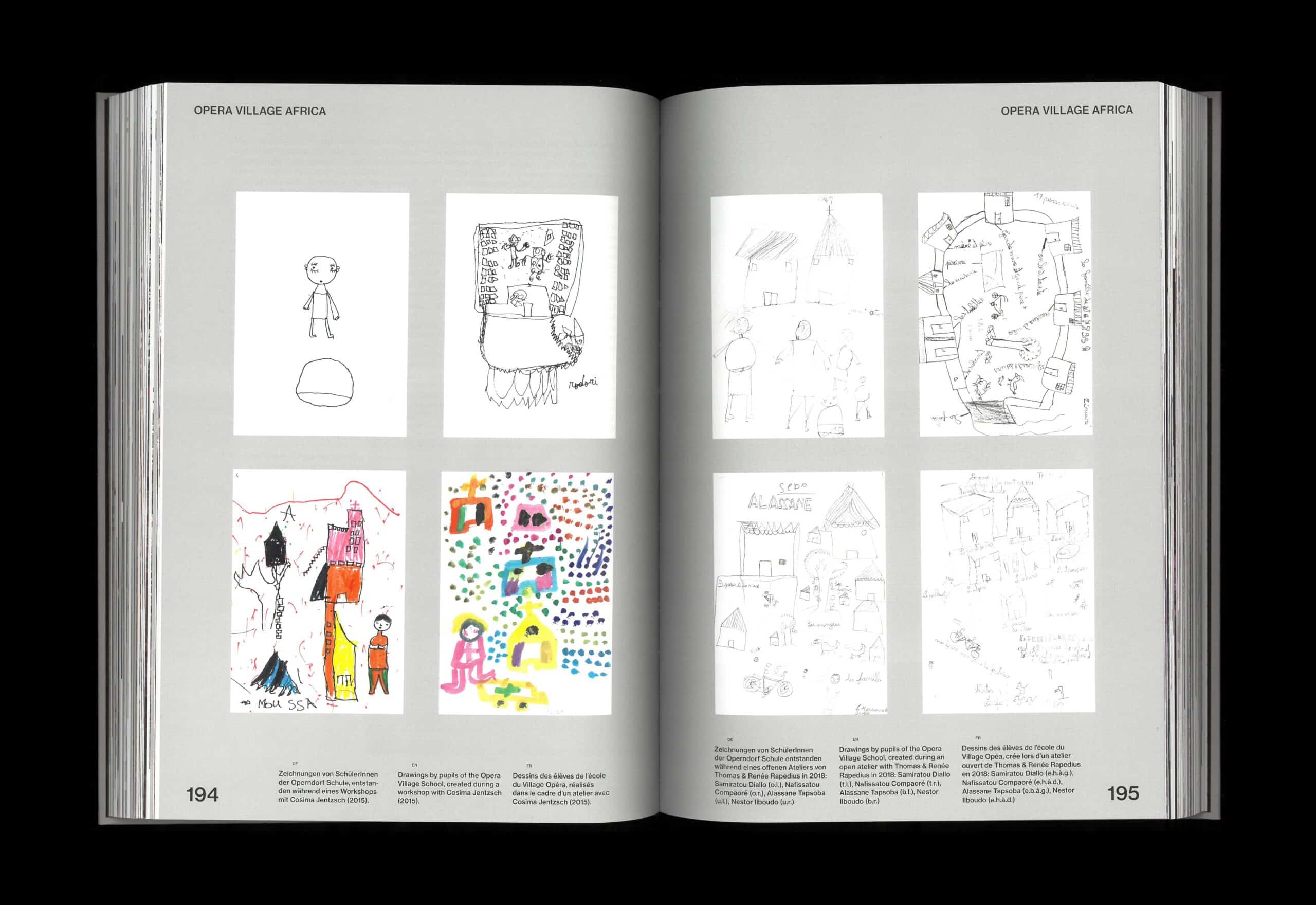

Providing care is an important part of the work carried out at the Opera Village. Burkina Faso’s Ministry of Education acknowledges the model character of the on-site primary school, upholding it as an example to strive towards. In its promotion of gender equality, girls complete four more years of education than they typically might, and they are encouraged to continue their studies. Additionally, the school emphasises art education, as a means to cultivate increased self-awareness in students, in order to encourage them to seek future employment that is aligned with their strengths. This is a thoughtful and ambitious offering. Alongside the school is an infirmary, which consists of an emergency room, a maternity ward, a pharmacy, and a dental practice, with attached housing for the staff. This facility was opened in 2014 and provides around-the-clock access to medical care for the region.

The complex hosts an accessible cultural programme that includes theatre and dance performances, film screenings, and concerts, as well as creative workshops for the community. These events are designed and organised, by the local program director Alex Moussa Sawadogo, in cooperation with various local cultural institutions and artists from Burkina Faso, as well as with the Goethe Institute. All the various programmes that are hosted by the complex, along with the building’s construction and maintenance, have the added positive impact of bringing jobs to the community.

The large-scale undertaking of the Opera Village is driven by Schlingensief’s vision, one that was not initially embraced by the Burkina Faso-based, German development community. In an interview that appears in the book, Kéré provides some interesting background:

They thought he was a provocateur, an artist who would damage Germany’s reputation in the field of development aid … Yet Christoph was someone who genuinely appreciated this continent and its people and took them seriously.

This is not easy terrain to navigate, especially for a foreigner such as Schlingensief, who seemingly had limited experience with such work and the German government’s concern seems appropriate as it takes effort and experience to understand how to be useful in an unfamiliar environment.

Eventually, the German development community came around. The Opera Village initially received financial and logistical support from the German Federal Cultural Foundation, the Goethe Institute, the German Federal Foreign Office, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, the Association Grünhelme, as well as private individuals. Since 2011, the project has been under the patronage of the former Federal President of Germany Hörst Köhler. Alongside that of the Germans, Schlingensief describes the positive support from local community leaders: ‘The councils of elders interrogated the building site and the spirits and ancestors living there, who decided that the Opera Village is very welcome’. In the end, the long-term community involvement in the realisation of the project will do the most to ensure that the community feels the necessary pride and ownership to perpetuate and maintain the Opera Village.

The Opera Village team approaches their work outside Ouagadougou with a grounded openness. There is an apparent questioning of their role in the process and of how to make the community central, from the immediate to the larger scale. For example, some important considerations when building in many low-income countries are highlighted in the book, Operndorf Afrika. Kéré explains how, ‘The land the government wanted to give us went against the vision of [Schlingensief’s] project, namely, to build and provide access to more than just the upper classes’. This is significant because while the difficulties brought on by Western intervention in low-income countries are well documented, what is less known or acknowledged is the negative impact that the existing class systems in many low-income countries can have on their citizens. The Opera Village project seeks to address this, intentionally and relevantly making a space that is: ‘Not only built for the elite few, in the rich neighbourhood of a capital city, as people expected both in Germany and Burkina Faso’.

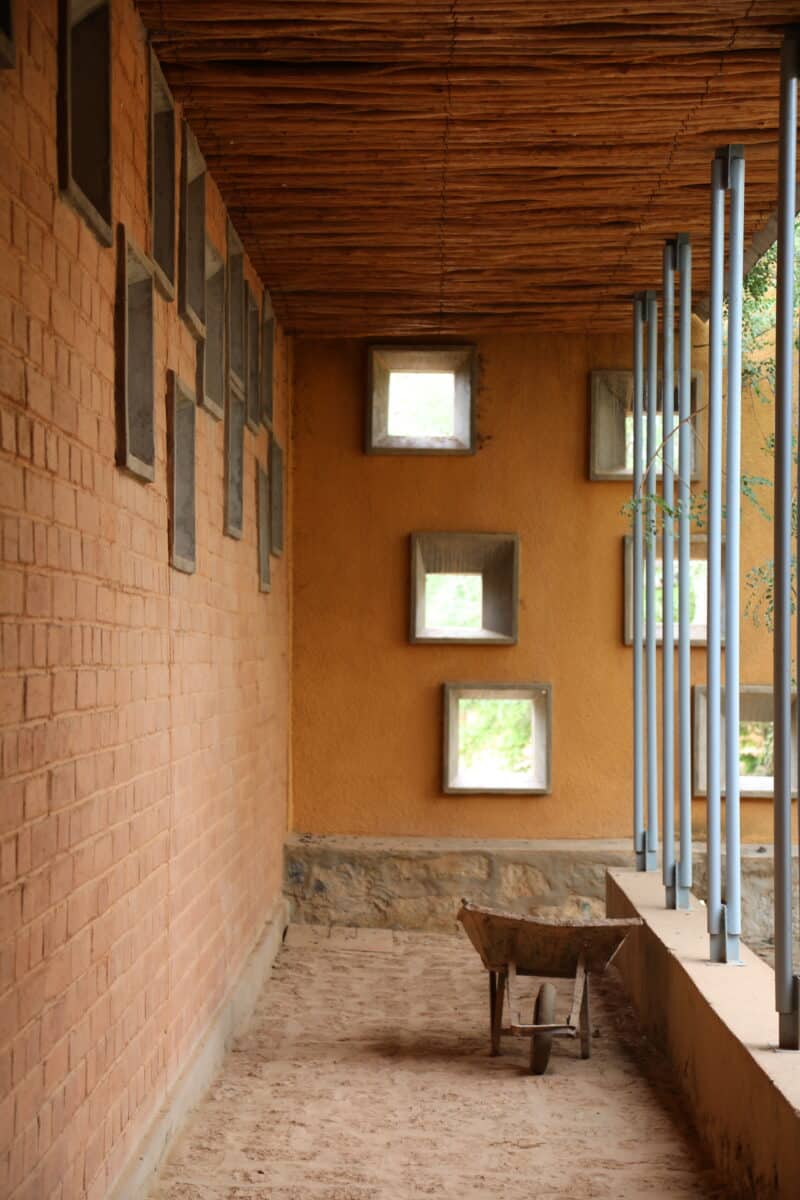

Schlingensief’s motto for the project was: ‘the place defines you; you don’t define the place’, and in this, client and architect were aligned. Both Schlingensief and Kéré viewed the work as a joint project with the community. They employed local people and worked with found materials. On site, the existing rocks and trees remained while the compressed earth block architecture with passive ventilation, incorporates traditional designs and contemporary methods.

There are moments in the book where further clarification and contextualisation would be useful. When non-Western narratives are presented within a Western architectural context, there can be a tendency to attribute methods and approaches to an individual architect or project, without understanding that these ways of doing are bound to a context and may be regional. This novelty may be an expression of a writer’s lack of familiarity with their subject, where local construction approaches are confused for a larger paradigm shift. The book does not adequately distinguish how the methods used to make this project sit in the larger context of production in the region. Doing so would better enable the reader to understand how the Opera Village conforms to its context and how it differs in this regard.

Similarly, a provocative statement is made by Laberenz, who says that the Opera Village is shaped by various approaches that are critical of conventional development methods. It would have been useful to unpack how the Opera Village both intersects and departs from traditional approaches to development. The reader is left to fill in the blanks here, which may be problematic for a Western audience who may be unfamiliar with Sub-Saharan Africa and Burkina Faso in particular.

Reflections on approaches taken by ‘conventional’ development projects would provide greater clarity to where the Opera Village is situated within a wider field of similar initiatives. In this regard, the publication could perhaps have benefitted from some expert insights on topics like low-cost architecture, West African architecture, or architecture for development. Another useful addition may have been to include interviews with artists who have participated in their intra-African exchanges, which would help to generate a better understanding of the scope, experience, and potential of the programme.

Related to this there are some foundational questions that go unanswered in Operndorf Afrika an important one being: What motivated Schlingensief’s artistic, social, and architectural engagement with Burkina Faso in particular? Alongside questions such as this, there are larger conversations around both this book and the project itself that go unexamined. The opportunity to offer a project like the Opera Village to a community, one supported by influential people, is not available to just anyone. Accordingly, not many schools in Sub-Saharan Africa, let alone the world, have European design publishers documenting the effort and the vision that brought them into being. Schlingensief’s privileged position is not lost in these pages and addressing it in more depth may increase the relevance of this book.

The publication presents a mix of commitments that have been made and questions that have yet to be answered. For example, Schlingensief’s 2010 suggestion of limiting himself to funding the Opera Village and not intervening in the organisation’s future affairs. While this open-ended thread reads as an acknowledgement of the complex issues that a project like this must navigate and even possibly the realisation of the critical importance of enabling Burkinabé people to determine their own future, the chance to explore these conversations, is not taken in this publication.

Operndorf Afrika’s pages hold a confession that things are ‘not perfect’, but the nature and location of this imperfection is left ambiguous. Nevertheless, there is something positive and reassuring in the simple acknowledgement that there is work still left to be done.

Christoph Schlingensiefs Operndorf Afrika (2020) edited by Aino Laberenz is published by Gall Editions. Copies of the publication can be purchased here.

Erandi de Silva (@erandidesilva) is a Ghana-based architect. She is the editor of Loké Journal (@lokemaking) which features inclusive, cross-cultural, and global perspectives on design.