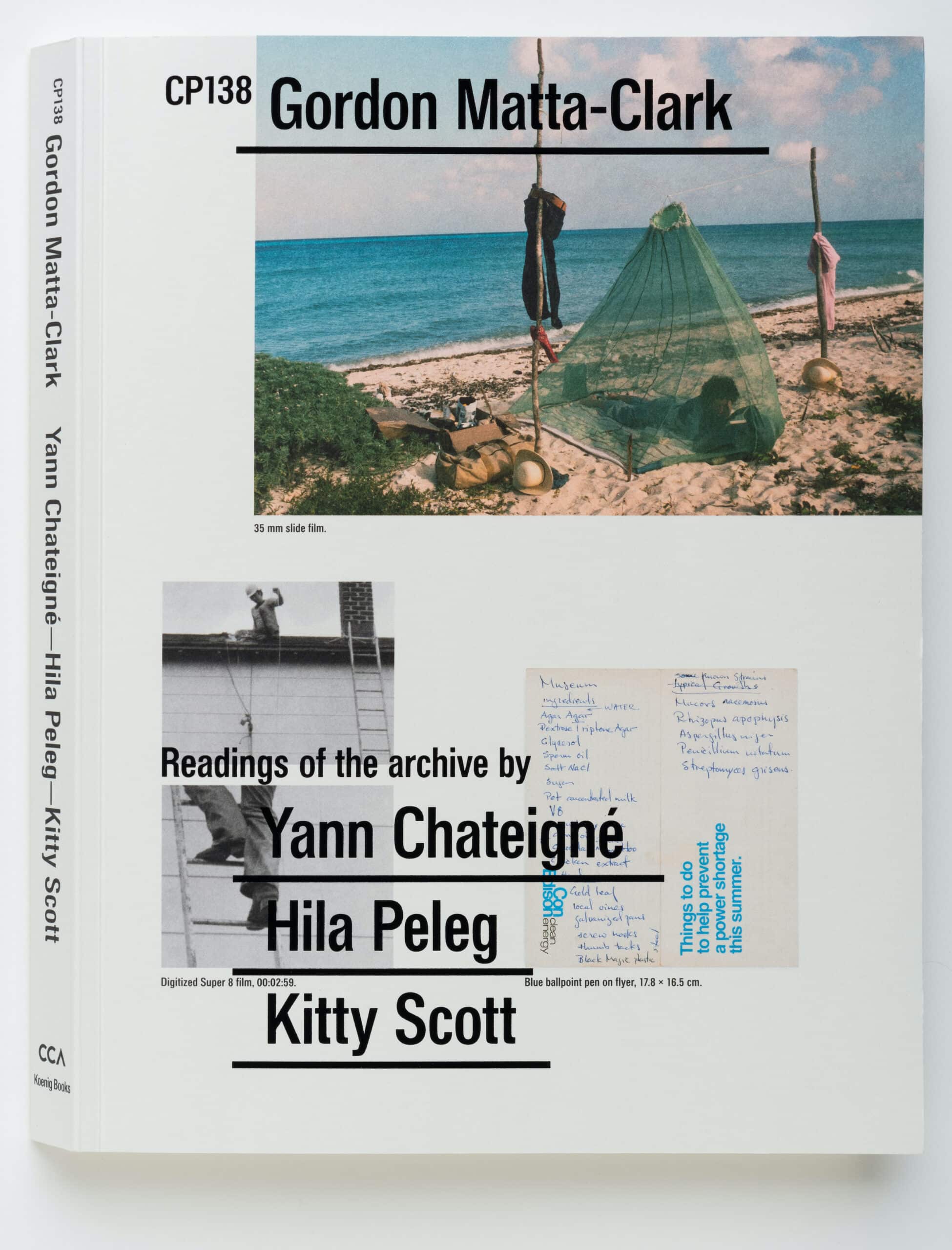

CP138 Gordon Matta-Clark: Readings of the Archive (2020) – Review

The Gordon Matta-Clark archive arrived at the CCA in Montreal 20 years ago. Shortly thereafter, it was used as part of an ‘archival exercise’: Out of the Box: Price, Rossi, Stirling + Matta Clark (23 October 2003–6 September 2004). That first ‘Out of the Box’ prefigures the one undertaken for this publication, which dates from 2020. Despite the apparently repetitive nature of the ‘Out of the Box’ formula, there have only been three editions, using several holdings: in 2003, 2015 and 2019/20. Each group of guest researchers was managed by a staff member, first Mirko Zardini, then Giovanna Borasi, and now Francesco Garutti. The guests this time are only three in number, and women are now included. They are Kitty Scott, Hila Peleg and Yann Chateigné. Each of them was invited to spend time with archive CP138 and then to make a show; their three projects are combined in this book.

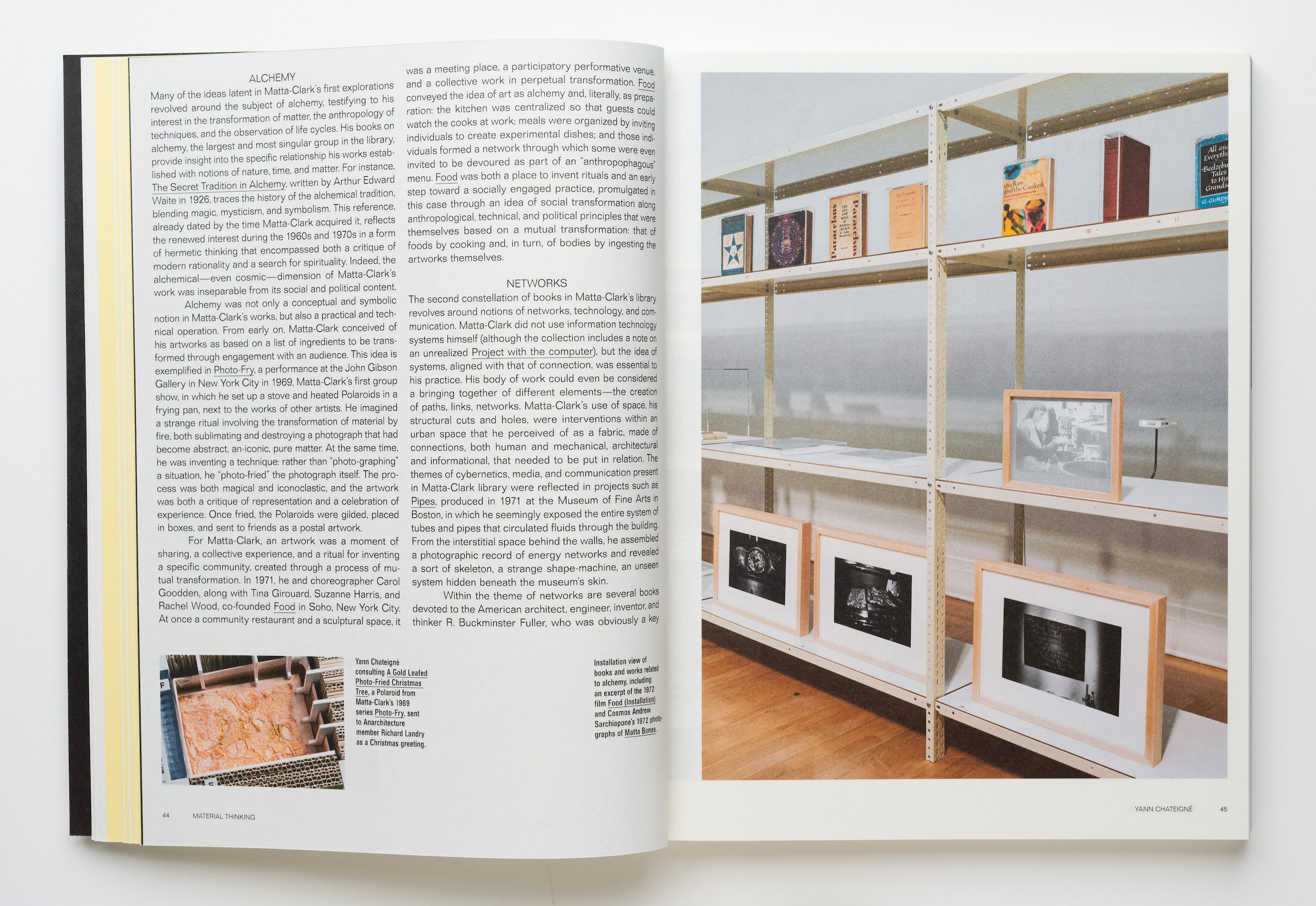

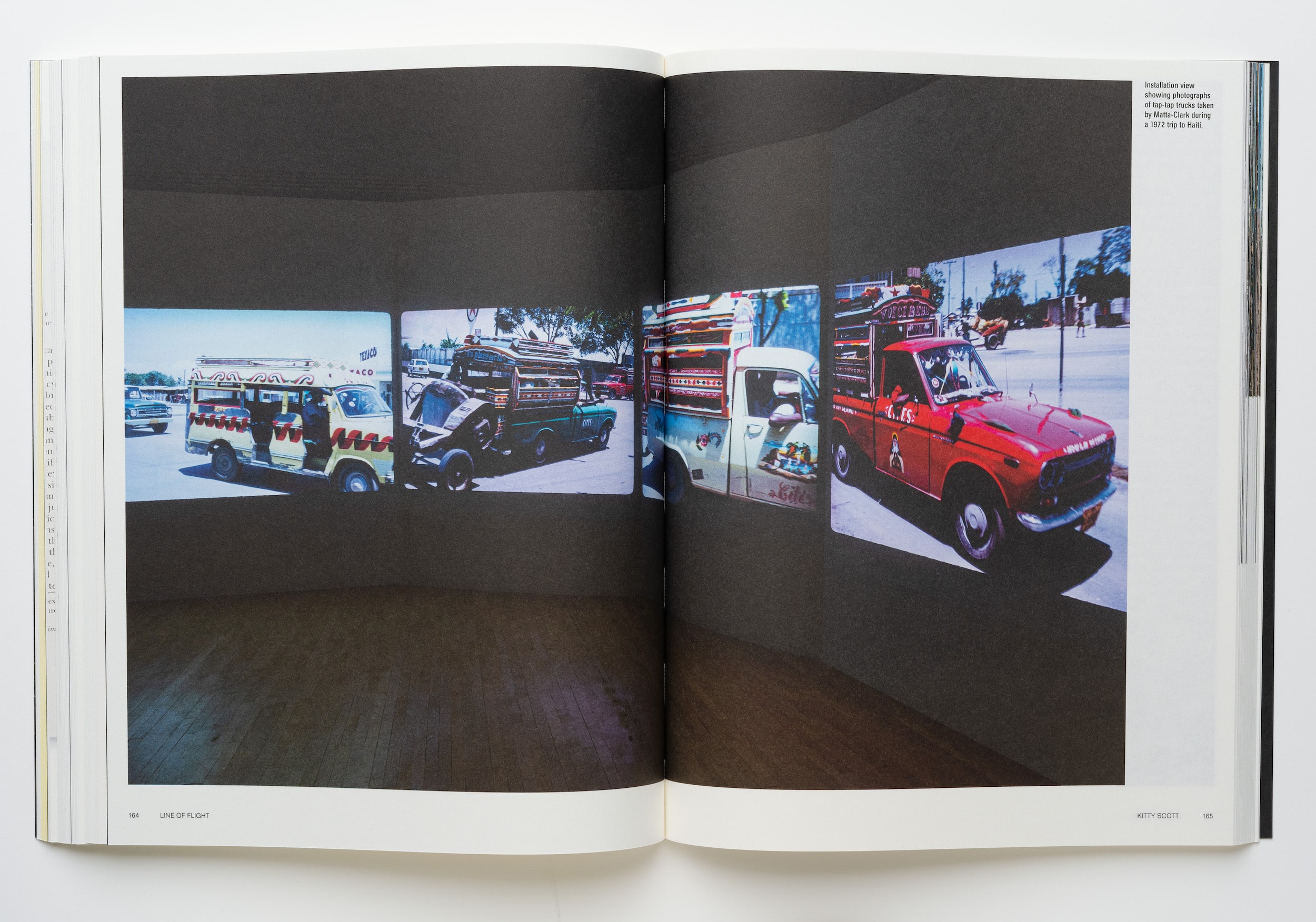

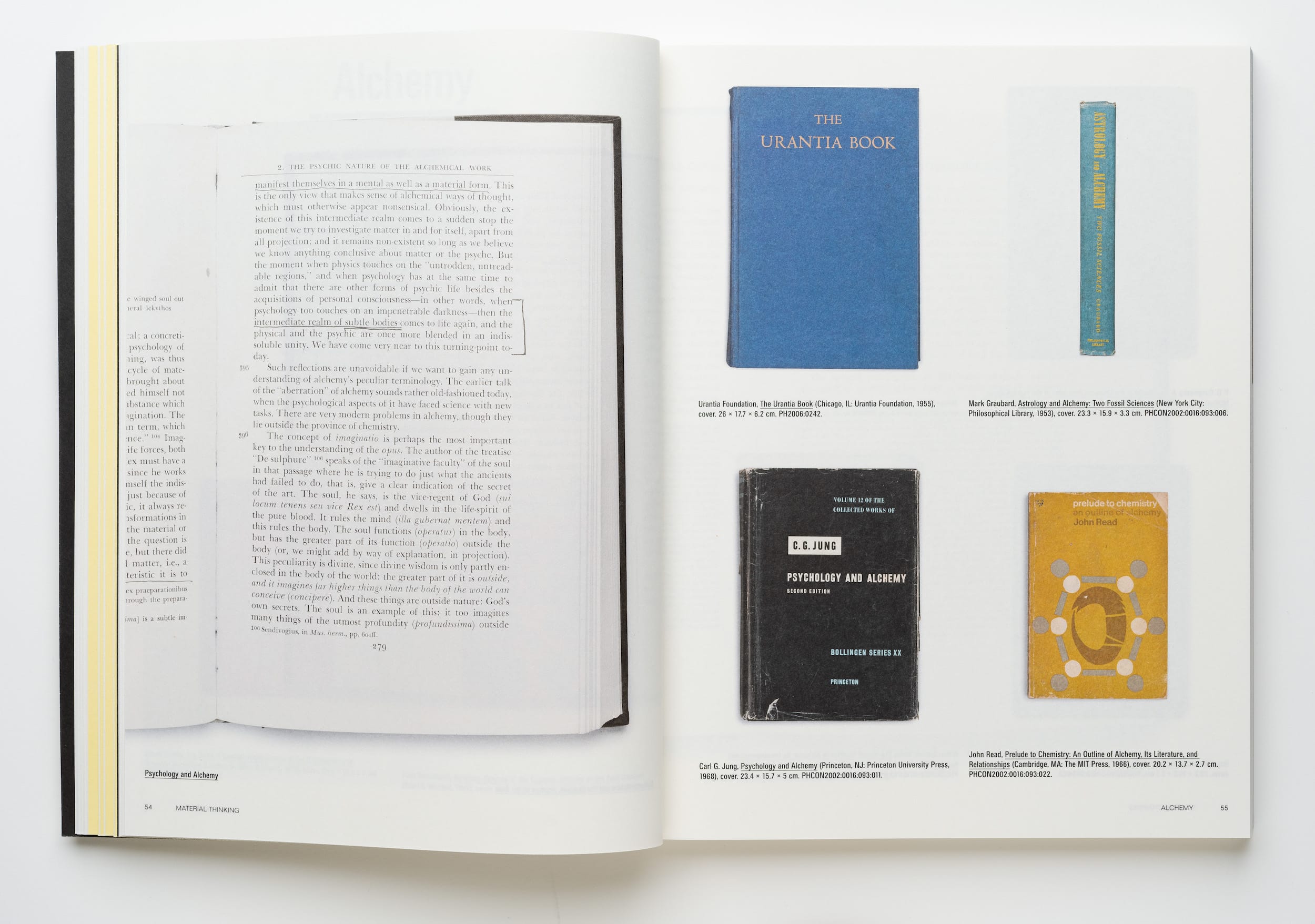

There are ten series in the Matta-Clark archive, which retains the order given to it by the artist’s wife: S1 Text Records, S2 Anne Alpert, S3 Photos, S4 Notebooks, S5 Artwork, S6 Film, S7 Library, S8 Artefacts, S9 Film and audio documentation on the artist, and S10 on his family and friends. These are listed with summary descriptions at the beginning of the book. Each guest chose one series: Scott, S3 the Photos, Peleg, S6 Film and Video, and Chateigné, S7 his Library. Each writes short introductory and section texts and the book includes some documentation of their exhibition installations.

I was asked by Drawing Matter to review this book, and I accepted, despite my protest about not being a specialist, because they said that did not matter. And to a degree I see what they mean, because it is hard to know how to review such a book. I feel a little as if that old adage of the blind leading the blind might apply. It is and it isn’t an exhibition catalogue. It is and it isn’t an archive inventory. It is and it isn’t a research project. It isn’t written by specialists.

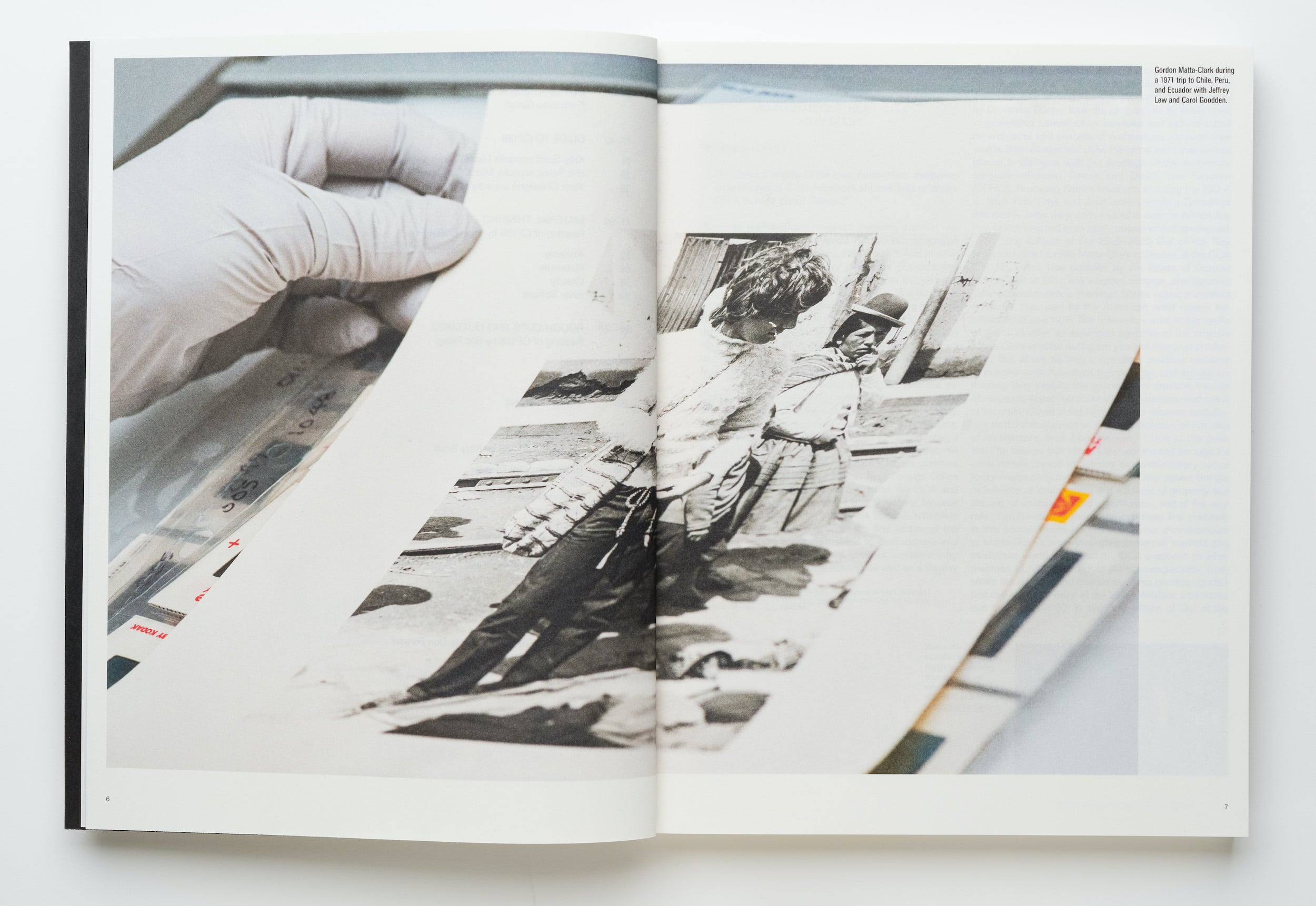

In fact, it would be good to know more about the authors, and why they were chosen as guests. I liked what they wrote and how they wrote it well enough, but I cannot judge how useful it might be to someone studying Matta-Clark for real. I don’t know if what they discovered for themselves are useful discoveries, and if they are, to what extent this publication does them justice. What I see is what I would expect, pretty much; a handsome book showing well-mounted exhibitions, and images of Matta-Clark’s travel photos, the covers of books from his library and of out-takes from his films. Each of the curators writes straightforwardly about their own time with the archive, readily admitting to their lack of specialist expertise. Given that this is a guest residency, it would be good to know what Garutti was looking for when he invited them, and to what extent it was a knowing invitation. Somehow the photographs of their hands holding archive material perpetuates a sense that their larger identity is either secret or unimportant. Surely this can’t be so.

Yann Chategné divides his analysis of the library into four sections: Alchemy, Networks, Gravity, Inner Spaces. His most helpful analogy is that with Kubler, whose famous work The Shape of Time is very much contemporaneous, and the images of the book covers help to implant a more fully grounded idea of Matta-Clark’s spatial underpinnings. Hila Peleg focuses on the rough cuts and out-takes from four films, Food (c.1971-3), Splitting (1974), Day’s End and Conical Intersect (both 1975). The archive yields up substantial amounts of additional film, audio and video recordings, several times longer in each case than the original. This was probably not the occasion for Peleg really to analyse what this additional material actually amounts to. Her brief summary is that it gives us context. Her analogy with the cone film of Anthony McCall, like Chateigné’s with Kubler, is helpful in giving shape to a contemporary idea. Scott’s trawl through the photographs was perhaps the most challenging because it is harder to differentiate it from other similar records made by equally fortunate travellers around the same time. It demonstrates that the artist travelled in Europe, North and South America, but appears to defy close analysis.

Gordon Matta-Clark died when he was 35. His archive therefore has an odd and uncommon relationship to his meaning as an artist; promising more than it (and perhaps he) could ever deliver. This book is something of a curate’s egg, and it is hard (if not impossible) to judge to what extent it does the archive justice, throws new light upon the practice, or suggests new lines of enquiry. It is notable that this research relies rather little on reading and is certainly not about reading letters. It is instead primarily visual. Its subject died in 1978. His parents died 20 years after he did. The box I most wanted to open was in Series 2 and included his mother’s letters to the artist’s father, the painter Roberto Matta Echauren, and her subsequent correspondence with Isamu Noguchi. This woman – an artist named variously Anne or Anna, Clark, or Alpert, or Matta – seems like a fascinating subject, and she would be my choice if I were invited to look inside CP138.

Yann Chateigné, Hila Peleg, and Kitty Scott, CP138 Gordon Matta-Clark: Readings of the archive (2020) is published by the Canadian Centre for Architecture and Koenig Books. Copies of the publication can be purchased here.

Penelope Curtis is a curator and writer.