Archives, or Ardor

Butter, fire, ardor: Roberto Calasso tells us that Vedic India is one of the earliest civilisations and one about which the least is known, having left nothing behind but a few fragments of enigmatic texts about worship and sacrifice. No buildings, no palaces, no traces of temples. Just the simple instructions of lighting fires and pouring ghee over and over again, to generate enough heat to bring down the gods.

What was the underlying reason for not wanting to leave any traces? The Westerner, with his usual euphemistic presumption, would immediately suggest the materials have perished in the tropical climate. But the reason is another—and it is mentioned by the ritualists. If the only event of any importance is the sacrifice, then what should be done with Agni, the altar of fire, once the sacrifice is finished? They replied: ‘After the completion of the sacrifice, it rises up and enters that bright [sun.] Therefore do not worry if Agni is destroyed, since he is then in that yonder orb.’ Every construction is temporary, including the fire altar. It is not a fixed object, but a vehicle. Once the voyage is complete, the vehicle can be destroyed. (Calasso, Ardor, 6)

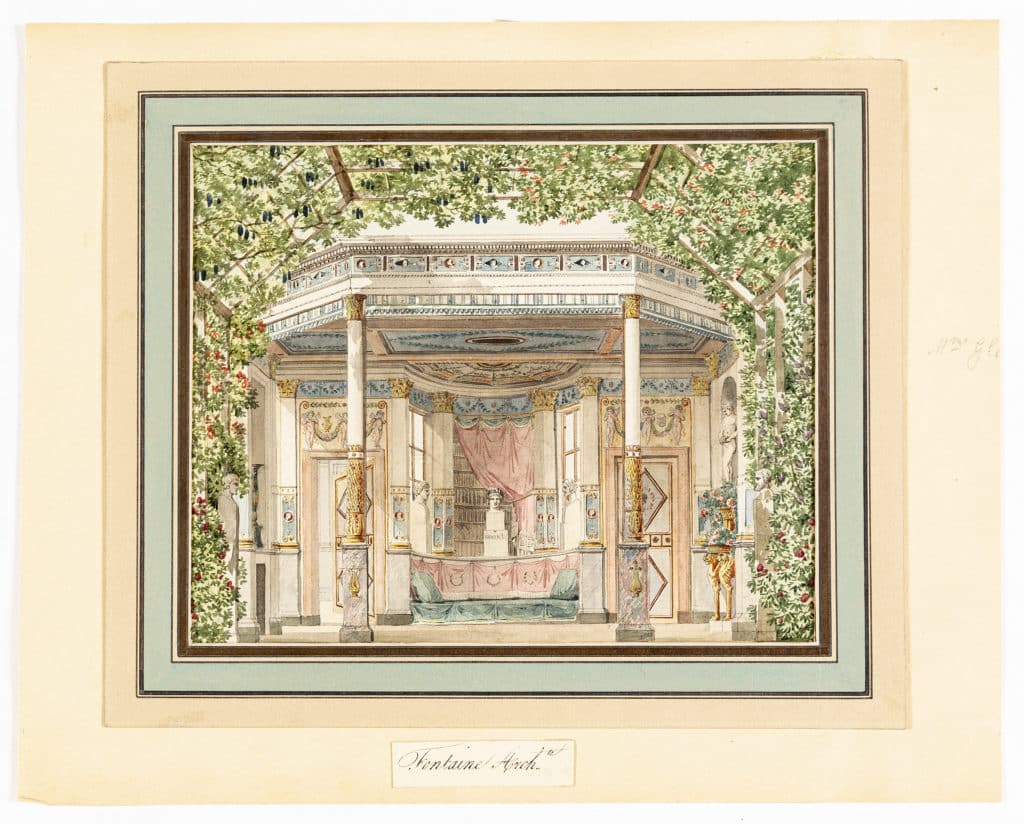

I thought of this heavy, mysterious stuff of Vedic India (but only retrieved the citation once back in New York) as I stood staring into the warm stove in the Drawing Matter archive at Shatwell farm. Now I can’t remember exactly, but there might have been some fur coverings (or lamps stitched and covered with skins) in this space, along with wooden furniture, shelves for the drawings, and some cabinets. And the black stove. The fire in the stove, lit by Niall before 8 am, is what worried me. That and the steaming hot coffee positioned precariously between a thick folder full of files on François-Joseph Belanger and Jean-Démosthène Dugourc, and the actual drawings the French architect-designers had made over two centuries ago. You see, I was alone, and worried that the place would catch fire and burn down the old farm in which the collection was now housed. And then I would have to use the coffee to put out this imaginary fire, adding an unwanted patina to drawings that had been made for a Spanish king or a French ballet dancer, the latter of whom Belanger married only after the two had been thrown in jail for being enemies of the French Revolution. A similar fear gripped me the previous evening at the thought that my son Egon, who crawled about on the floor of the archive, would pull a rare pen and wash drawing of a theatre down and crumple it in his greasy but adorable hands…

These imaginary scenarios of destruction didn’t come to pass, but did make me realise that archives often induce a fair amount of anxiety and paranoia in researchers, propelled by the worries about old objects being handled too roughly in the process of being studied. Conservators, curators, and archivists fight against time, seeking to preserve pieces that perhaps were never conceived to last so long. In the process, research becomes difficult if nearly impossible. Some places make you put white fabric gloves on to prevent your sticky hand grease from touching the paper and soiling it. Others limit your viewing time for fear that a drawing will disappear before your very eyes because of the carbon dioxide being expelled in your breath. Forget about children and mothers wandering about. Coffee? Out of the question. The strange thing about working in archives is that some strive to create impossibly clinical conditions, as if everything can be controlled like a trial for a new toothpaste that promises things that can be tested and approved. Archives do not exist in a vacuum.

This desire for pristine preservation undoubtedly has ties to the fact that so much of Western history has revolved around commemoration, about building things that last so they can be remembered forever and honored by future generations. The archive too has traditionally been placed on the side of this official history, as the place where the archons preserved the laws and defended them. Jacques Derrida tells us that the word archive stems from the Greek arkheion, meaning ‘a house, a domicile, an address, [of] the residence of the superior magistrate, the archons, those who commanded….On account of their publicly recognized authority, it is at their home, in that place which is their house..that official documents are filed’ (Derrida, Archive Fever, 2). What has often gone unnoticed in Derrida’s account of the archives is that this originary notion of the archive was already the home and the house of the archon. This means that official documents were first housed in a domestic space, an inside, a sheltered inner place where they had to have come in close contact to the hearth, the burning fire that was the original site of the inside. But also the making of its potential destruction.

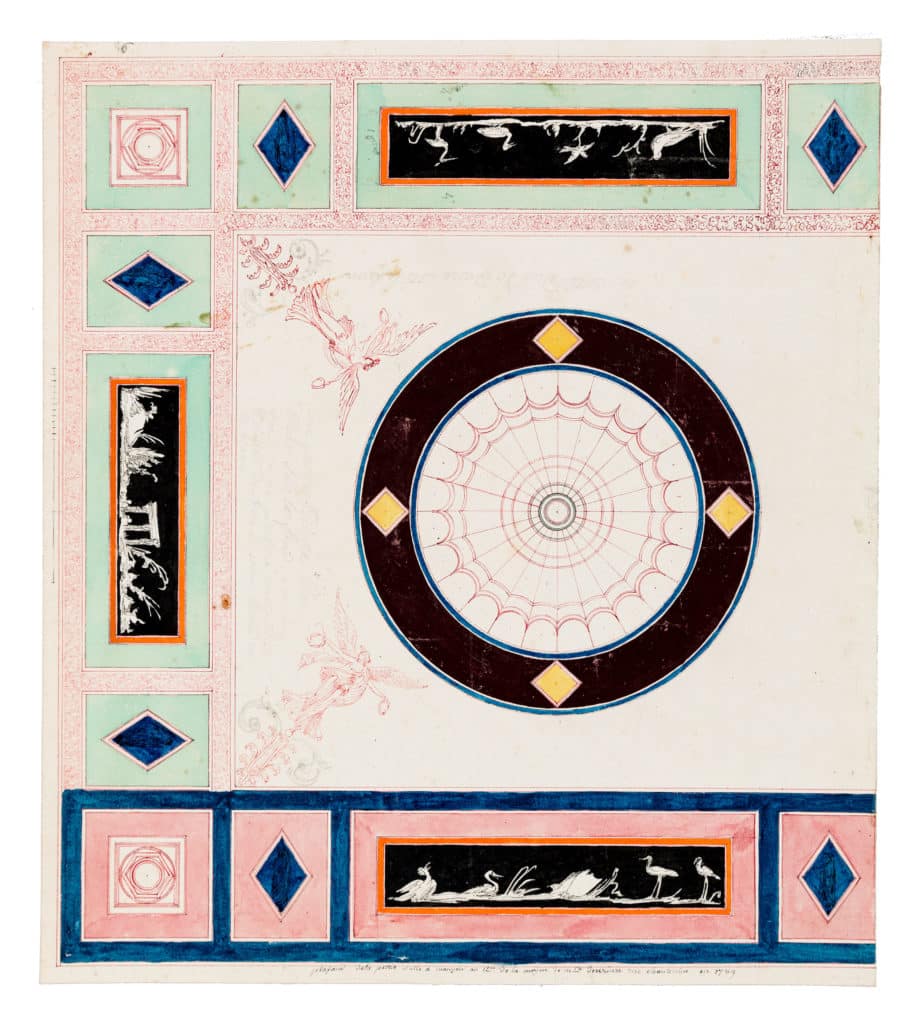

This is a long-winded way of saying a simple thing: archives have the power to spark fires. For when the fear dissipates, there is ardor: the flash of recognition in a space or representation that calls to mind other images in your head. Touching a drawing in a strange shape that makes you think: if most rooms are square, why is this one in the shape of an octagon? What rooms did an architect like Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine design in the shape of an octagon? And why would he need to lay a decorative skin over the whole room, instead of designing each individual piece one at a time in careful consultation with his client (as his partner Charles Percier certainly would have done)? Based on this scheme, his client clearly didn’t care about carefully selecting the contents of the room; he needed something sur-le-champ, a taste of haste that squares with the sort of military soldiers hired by Napoleon to keep his crumbling, fragile empire alive. Napoleon’s story of conquest is a part of the past now. But the drawing? A vehicle for something else.

A word of advice if you plan a visit: bring the fire; leave the butter at home.

– Niall Hobhouse