Drawing Architecture: Conversations on Contemporary Practice (2022) – Review

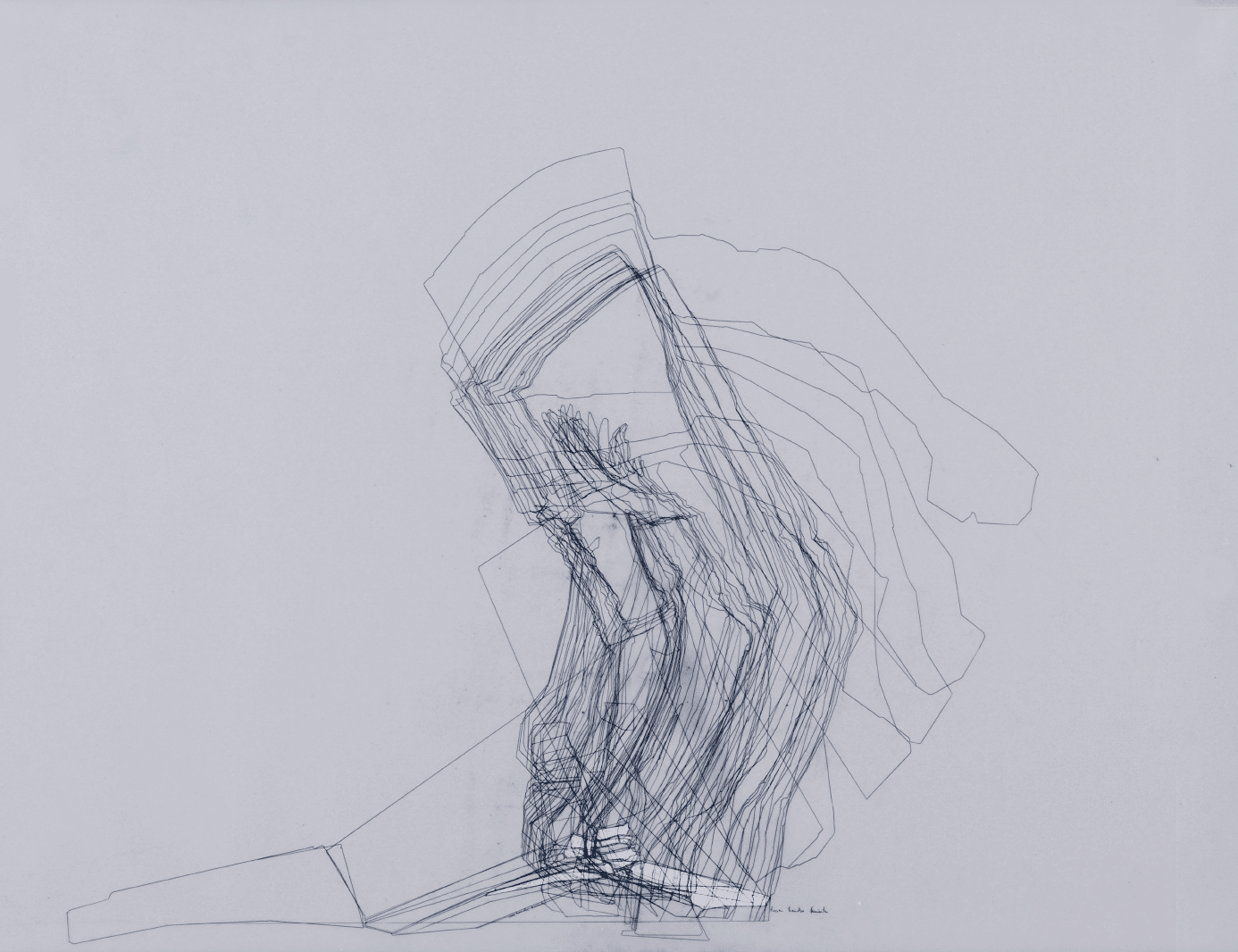

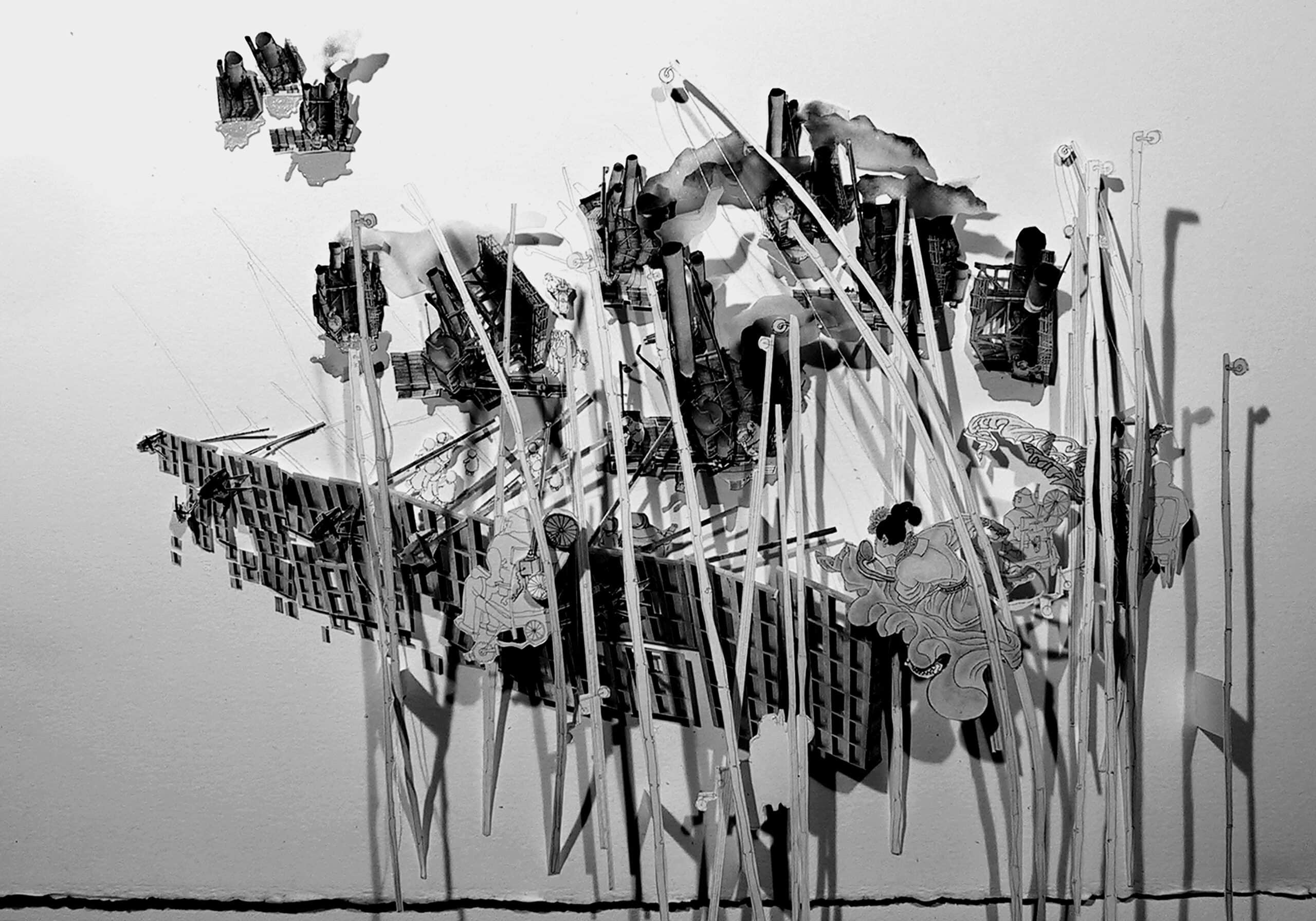

Flipping through the book for the first time, I discover its contents with a feeling of true ignorance and great excitement. The drawings are both very familiar and yet totally foreign. I am plunged into an intense atmospheric world of fantastical stories, cosmic adventures, archaeological excavations, and biological investigations in which architecture and spatial representation perform with playfulness. Some of the drawings are appealing, others are darker and almost repulsive, but a kind of cosmic joy sweeps over it all. The further I dive into the book, the more outrageously the different media blend together with increasing acceleration. Hypercreativity and hypertechnology frame images that become machines that propel emotions.

There is something euphoric and fascinating about these drawings that reminds me of a recent visit to the Graz Art Museum: a large, dark, plastic, glittering blue whale dressed with white, semi-circular LED lights, like small seashells, that flash through the cloudy Austrian night as Christmas approached. Experiencing it incited the memory of an epiphanic moment; why are we all craving for this? My encounter with this book poses a related question: what are the sculpting modes and mechanisms behind these drawings? Incidentally, ‘The Whale’ is one of the few projects built by Archigram Group member, Peter Cook who, along with fellow member Michael Webb, is one of the first voices taking part in the book’s fourteen conversations.

Research into the subject was initiated by editors Riet Eeckhout and Arnaud Hendrickx at KU Leuven University in Belgium. In 2019, they gathered a cohort of architects with the aim to produce and exhibit a collection of contemporary architectural drawing. For two years, they met every six months in different cities to discuss drawing. The book itself is an ambitious and dense report of these four sessions. Eighteen architects were invited, all of whom hold professorships or are involved in teaching and all of whom practice architecture through drawing, some exclusively so. They share a faith in drawing practice as a zone of inquiry, discovery, and exploration. The community defined by the book includes, in order of appearance: Mark Dorrian, Riet Eeckhout, Arnaud Hendrickx, Michael Webb, Peter Cook, Neil Spiller, Laura Allen, Mark Smout, Carole Lévesque, Thomas-Bernard Kenniff, C.J. Lim, Shaun Murray, Nat Chard, Bryan Cantley, Perry Kulper, Natalija Subotincic, Michael Young, Mark West, Metis: Mark Dorrian and Adrian Hawker.

In its formal density, the publication has the same sense of academic completeness that a manual might. The core material contained in the transcripts of the discussions was dissected, structured, reframed, summarised, and presented in various text formats for educational purposes. This creates a sense that the book cannot be fully grasped in one read, inspiring readers to revisit it multiple times to uncover new stories behind the drawings as they hone their own drawing skills. The book’s grand title suggests that it contains the essential knowledge of architectural drawing theory.

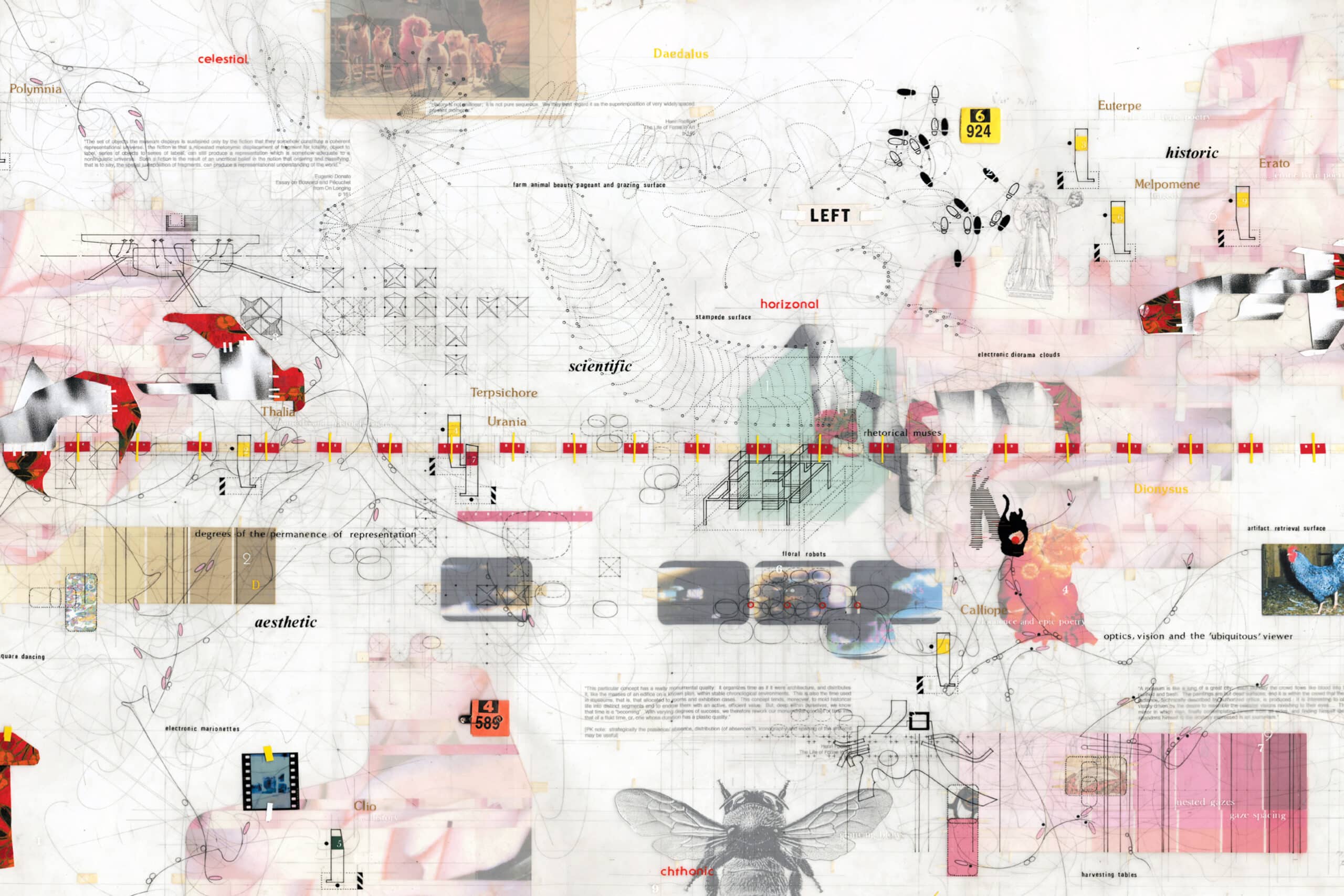

Organised into four sections: ‘Drawing as Material Practice’, ‘Methods and Modes of Working’, ‘Agency of Drawing’, and ‘The Limit Conditions of Drawing’, fourteen transcripts, four essays, and four glossaries weave a theoretical thread in search of a common thesis. Several black-and-white photographs of the symposium show the cohort gathered around large-scale drawings. Evident in the facial expressions, the images convey the sense of a post-pandemic joy of exchange and camaraderie along with the seriousness of the task at hand. Folded in between this varied content is an extensive collection of the drawings produced by the book’s participating authors between 1993 and 2022. The essays introduce and provide useful historical context to the open, sometimes vivid, discussion transcripts. Directly extracted from the architects’ distinctive lingo, the glossary keywords give polyphonic resonance to the common thesis. They allow the drawings to be approached from another level of interpretation that helps the reader to penetrate the complex mechanisms and meanings. The format of the book successfully supports a non-linear interpretation of the subject and its theory, which can be enjoyed equally by the amateur and professionals.

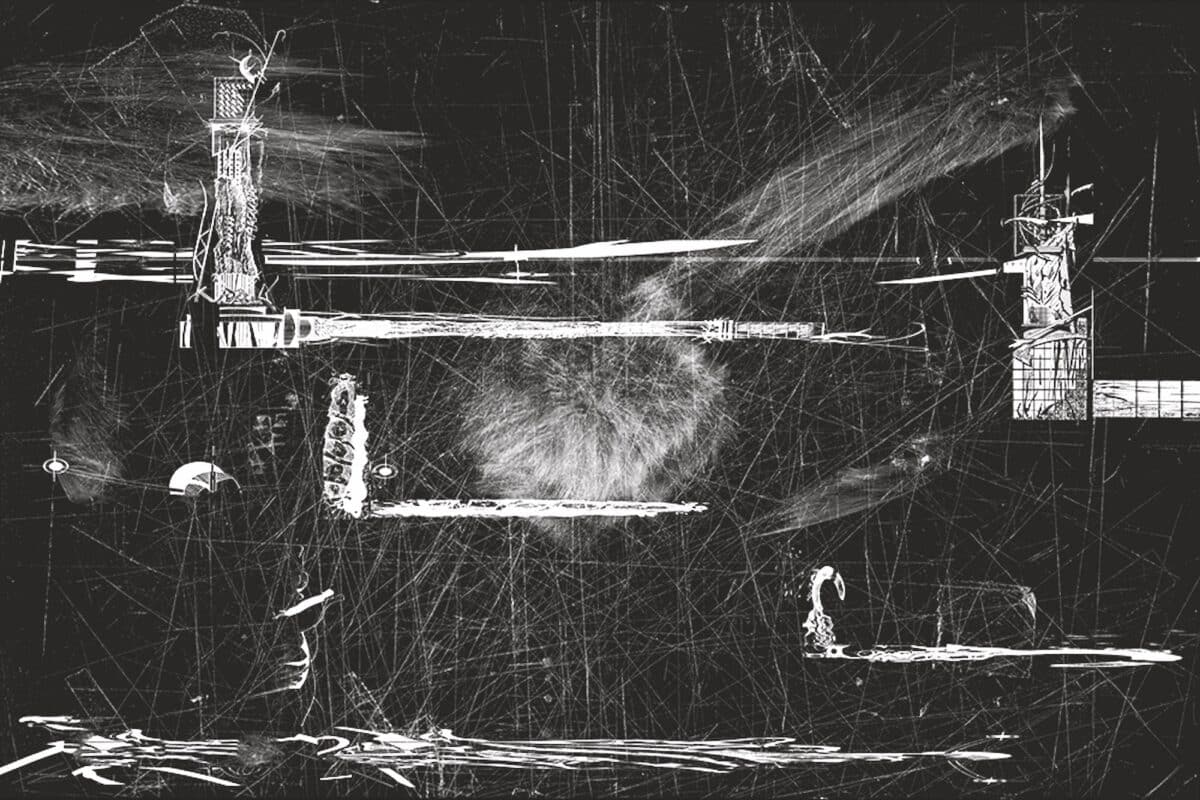

Some of the questions raised by the drawings seem self-evident in an academic context but, for students especially, there are some useful reminders. Peter Cook helpfully dwells on the power of failure, or ‘how to deal with fucked-up drawings’, as he addresses the ‘fetishisation of drawing’ trap. The obsessions of the participants emerge in personal anecdotes told during the conversations. Neil Spiller, in his conversation entitled ‘Prerequisites for Discovery’ with Michael Young and Mark West, for example, focuses on the choreography of the random. He leaves place for chance and noise, the opposite of cleanliness. The traces of the tables notched by earlier coups of cutters on which he draws appear in his compositions. Scratches appear here and there, evoking landscape or meteorology elements. They become an integral part of the narrative conveyed by the drawing, and anchor the image in the place where it is made.

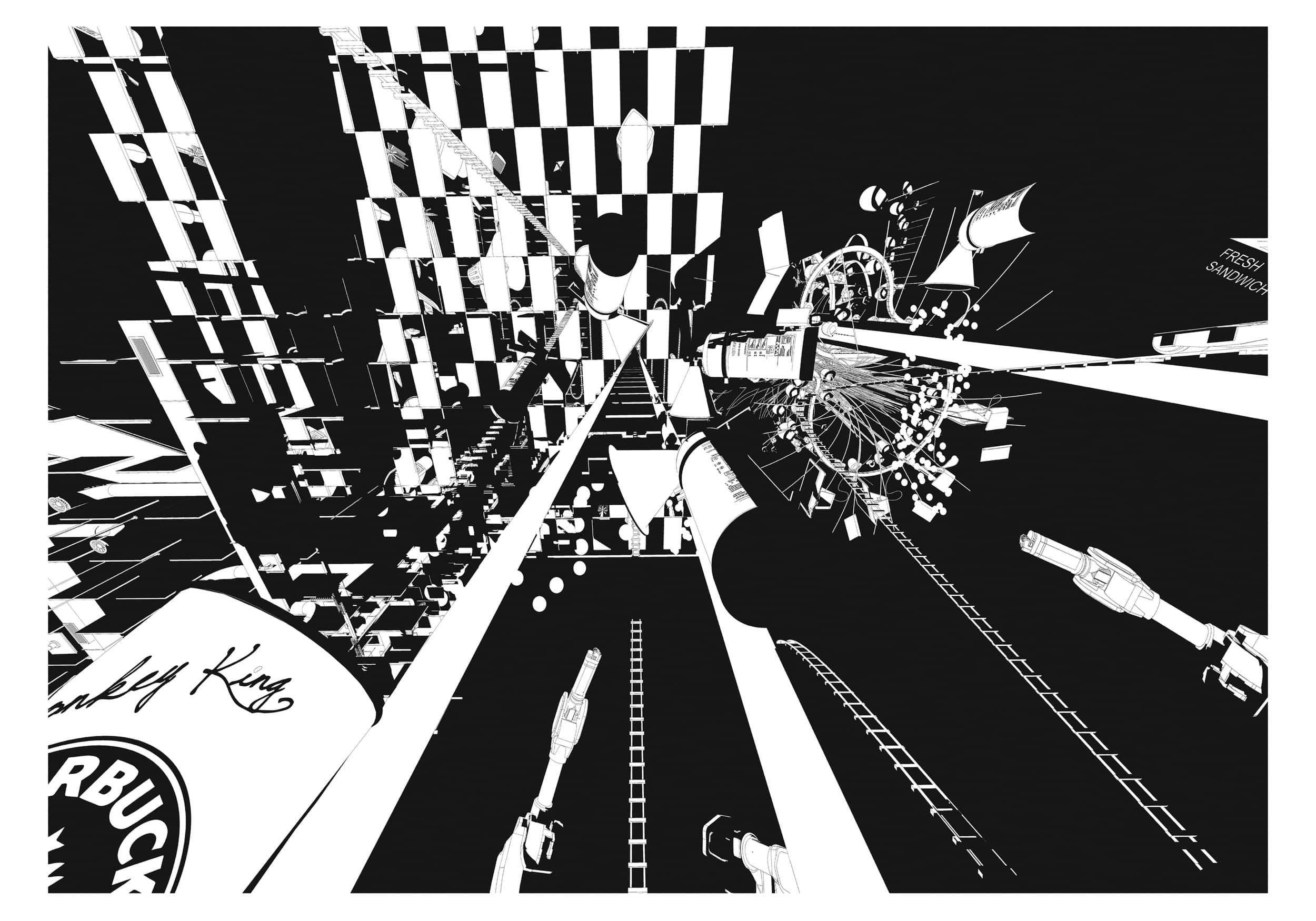

Bryan Cantley, in a conversation headed ‘Media-specific Impregnation: the Drawing as Subject’ with Nat Chard, addresses the mechanisms which make drawing an act of communication. He makes us aware of the architectural policies contained in the lines by playing with the annotations specific to the representation and the description of construction. The architect-duo discuss image-making tools that are changing, hyper-expanding, and yet easy for everyone to use thanks to the open-source support of the web community. How we appropriate them, regardless of technique, is what pushes the limits of architecture. It is the vision that counts. Throughout the book there is a systematic celebration of the role of intuition, the experimental, and the speculative as a form of freedom, accompanied by the sense that architecture as a conduit of cultural debate raises questions beyond the resolution of functional and programmatic problems.

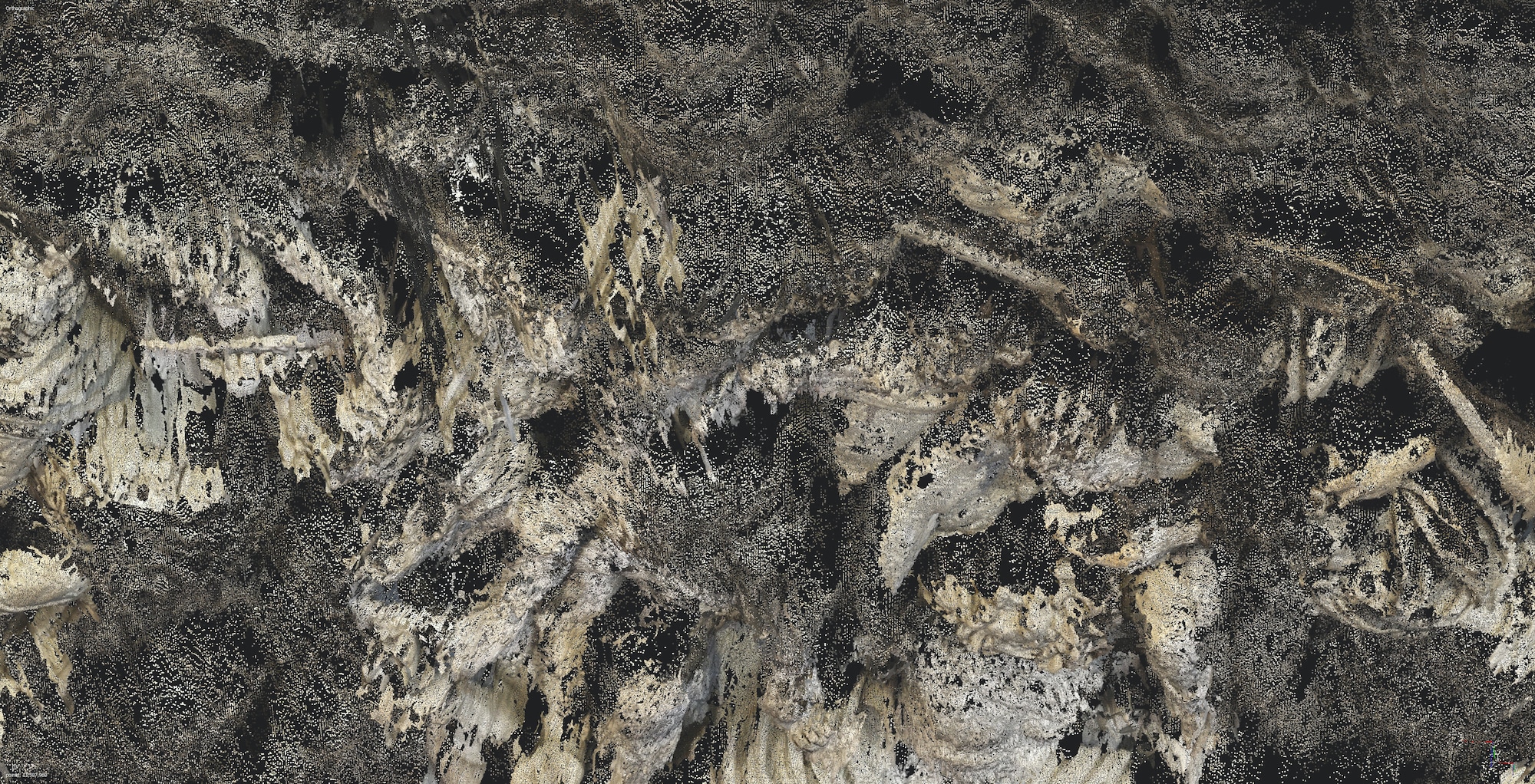

Michael Young’s work around photogrammetry engages with tools that provide a new way of perceiving and describing our environment: a world where spatial qualities are shifted; a world of millions of points where proximity does not increase realism, but increases abstraction. This raises the question of how to deal with the overwhelming amount of data it is possible to survey and collect. Nat Chard places the ‘Picture Plane’ and the perspective invented by Brunelleschi at risk with his spaceship-like drawing machines that spit at each other during paint battles. His creatures deconstruct our conventional relationship to space and challenge us to think about a world we cannot truly grasp. ‘Is this work art? Do you consider it art?’ asks Anthony Morey, ‘or is this architecture?’, in his conversation with Mark West. The ambiguous friction between art and architecture looms large throughout the book in its investigations into the mechanisms that drawing convokes for the different practices. We learn how the creative process of architectural drawing contains the reveries that help architects to answer questions around how we should live in this world, and what this world could be like.

Visual constructions have the ability to change an architect’s conceptions of reality, to influence and seek the interpretation of the work which, in turn, transforms the mechanisms into a new form of knowledge. The contributors oscillate between discovery and invention to the point of losing control. In my mind, this raises a question of particular and urgent concern to today’s generation of students, which is how are the architectural practices represented in the book funded? The book provides valuable insights into alternative approaches to practicing architecture that challenge the dominant capitalist framework, but also offers room for further development.

Mark Dorrian, Riet Eeckhout and Arnaud Hendrickx eds. Drawing Architecture: Conversations on Contemporary Practice (2022) is published by Lund Humphries. Copies of the book can be purchased here.

Emilie Appercé is an architect founder of Zurich International, diploma/studio assistant at the Department of Architecture, ETH Zürich and an editor of Women Writing Architecture.