Growing up Modern: Childhoods in Iconic Homes (2021) – Review

What do our birthplaces do to us? Should those homes be considered modernist jewels, the pride of their architects and, sometimes, of their patrons, how would that particular experience be imprinted on their children? Growing up Modern is a highly personal book in which the authors, Julia Jamrozik and Coryn Kempster, themselves partners in practice and in life, as parents, probe the possibilities of oral history as an architectural reflection. It can, they write, add a fourth dimension.

Responding to them, a handful of very old people have looked back at their early experience of childhoods spent in famous examples of pre- and immediate post-war modernism. Their memories are surprisingly varied and even unexpected. These houses were designed ‘as places that harboured life’, yet the children’s provision was largely ad hoc, of their own making and recall, and it was gardens and terraces that had lingered on in their memories, as recalled in 2015. As a useful guide, even summary, there’s a series of carefully annotated plans, plotting memorable episodes and places that the interviewees mention.

Pankokweg 3 was Rolf Fassbaender’s home in the Weissenhofsied for twelve years from the age of two. His father was a singer who moved to Stuttgart from Aachen in 1927 on the offer of a contract by the city. Public housing came with that, for this family in J. J. P. Oud’s self-effacing terraced row for the ‘sensible middle class’. An only child, a high point of his enduring memories were the bonds made through friendships with neighbouring children, maintained long after. These arrangements did not stop at anyone’s front door, certainly not at No. 3. The close quarters in which they lived included very poor sound insulation between the five houses.

As if to compensate, the little gardens and the living rooms (the living room was the centre of life, his family’s focused on a friendly round table), became interchangeable spaces for all. The all-important Erna Meyer-designed ergonomic kitchen may have passed him by, but he brought his own signature to the house. He remembered, his enchantment ringing out decades later, how he colonised the tiny balcony outside his bedroom. By pulling out as much of the mattress as he could, and easing himself onto it, headfirst, on warm summer nights he slept half outdoors ‘under the sky, under the stars.’ Oud’s neat touch, the cantilevered balcony doubling to form a canopy over the door where a little outdoor bench sat, (perhaps a touch of Dutch cottage style slipped into a modernist carapace?), still delighted Fassbaender in his late nineties. There is no more moving moment in the book, resounding evidence of what Gaston Bachelard suggested we take as the ‘motionless’ memories of distant home.

In rather chilling contrast, memories of the Tugendhat house in Brno designed by Mies van der Rohe, as described by Ernst Tugendhat, who lived there for the first eight years of his life, is shot through with antipathy, to the particular as to the general. ‘It was quite unimportant where I lived. I’m a philosopher.’ Later, he convinced himself that he would have been mortified by the palatial extent of the house. In the interview he apologised for not offering a more positive response to the ‘icon’ in which he had spent his early years – a house sufficiently renowned to have even inspired a work of fiction, Simon Mawer’s The Glass Room. There, the three children and parents lived in defined, separate quarters, along with some of their large staff. It was not, he considers, a creative or free environment and the desperate circumstances under which the family left Brno, on the approach of the Nazis, only serve to intensify these feelings. The house, in his mind, only endured via those items of furniture which the family had taken with them into exile to Switzerland, Venezuela and back again to Switzerland. The famous library and Brno chairs offered Tugendhat some affinity, rather ‘than the house itself.’ The photographs, after the rigorous 2012 restoration of the cold house-museum, inadvertently reflect Tugendhat’s measured distance from that terrible past.

The Schminke House is another strong contrast. The family, owners of a pasta factory, lived there from 1933 until 1951 and the interviewee, Helga Zumpfe, the youngest of four children, was the reason her parents commissioned a new, and larger, house. Its architect, Hans Scharoun became part of the family, as sparkling family photographs show, a deep friendship resulting, long after, in Mrs. Zumpfe gaining him a commission for her parish church and community centre in Bochum. The boat-like form, the generous open space and water surrounding it, and the effortless coexistence of children and adults are luminous tributes to the design. ‘My memories of the house are of the light – expanse and joy.’ Their playroom was at the centre of the house and full of child-centred special touches. They could clamber out through low windows into the garden while the doors incorporated coloured ‘portholes’ so that ‘one could … always see the world in different colours.’ Everything was open, interconnected rooms fed into one another. Helga Zumpfe followed that in her own house, removing doors and replacing them with curtains, as Scharoun had done. ‘I still dream about the house in Lobau.’ In reality the house is now a museum.

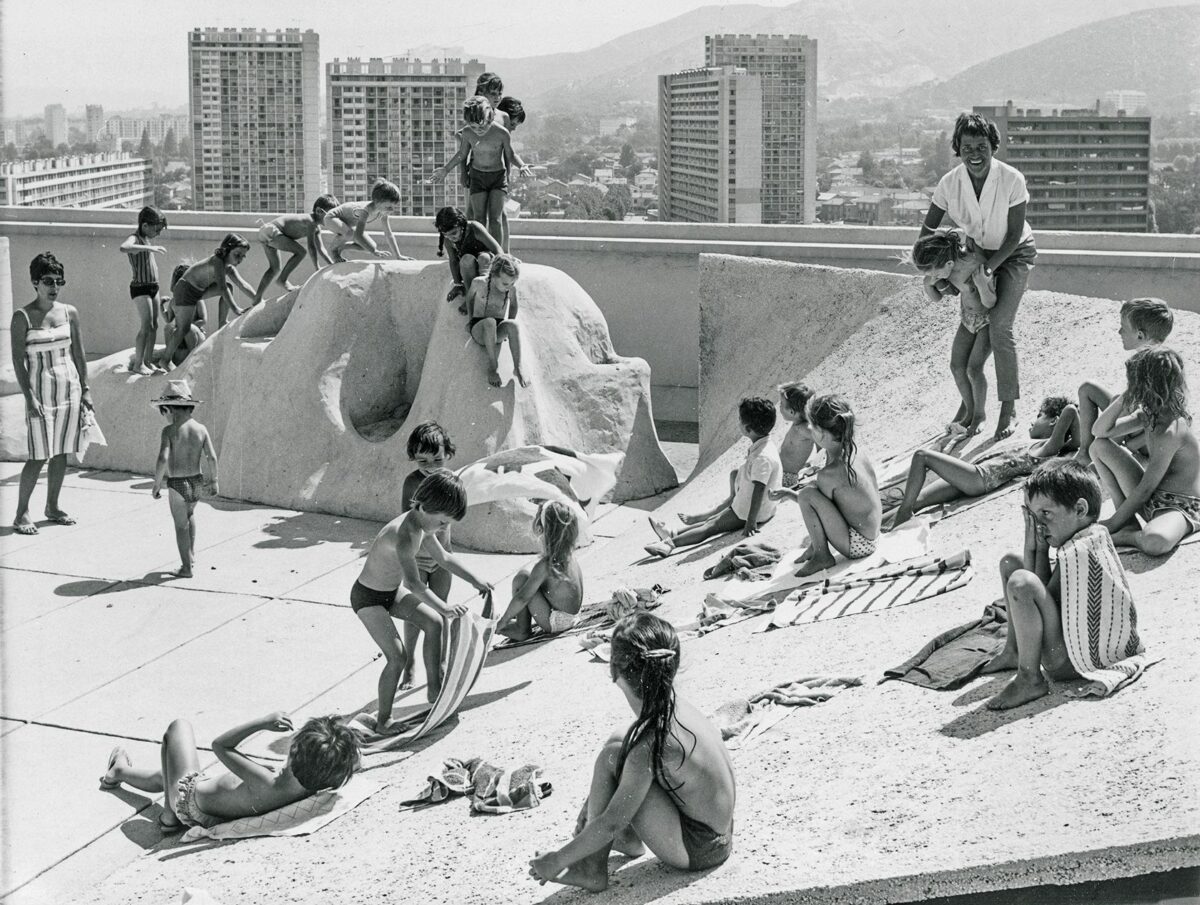

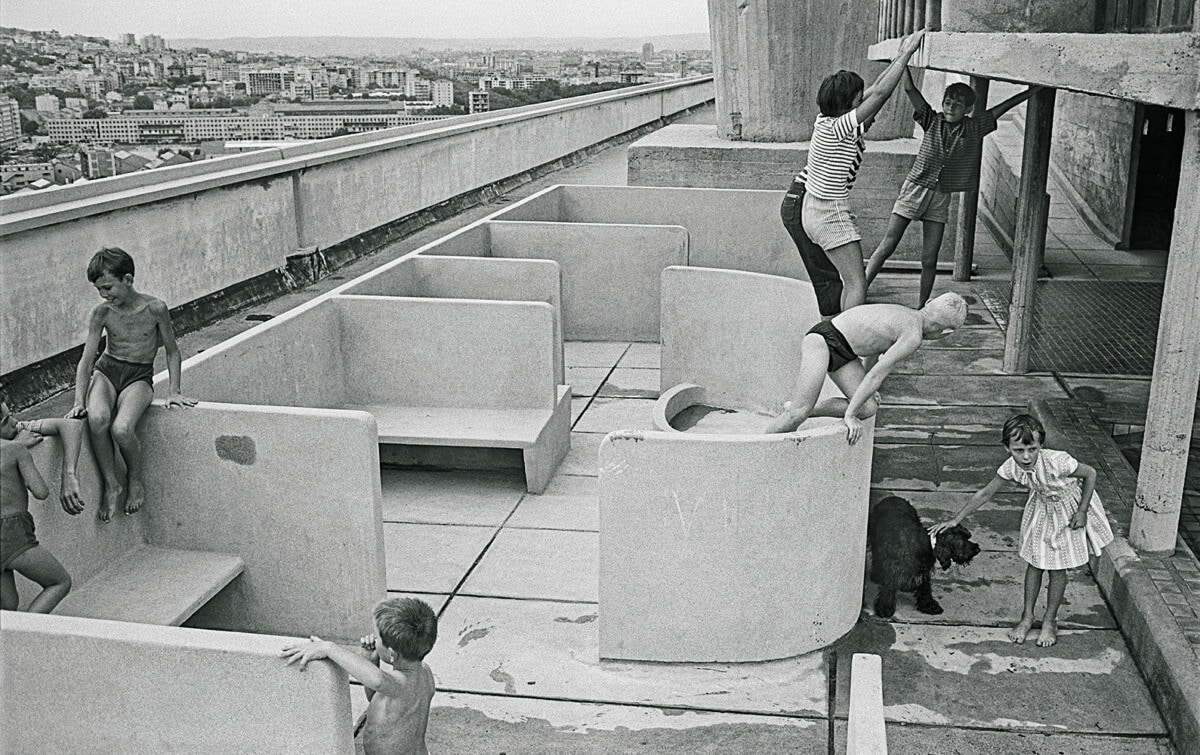

The fourth example is the Unite d’Habitation in Marseille and here the interviewee, Gisele Moreau, has lived in the complex almost all her life – as child, parent and grandparent and as a result ‘the mythology of the place has become a strong part of her personal story’. Her emphasis lies rather with the communal aspect of the place. The dreamscape on the roof, which she still sees as ‘a miracle’, the paddling pool and the concrete rocks of the play area, has helped to make the Unite ‘the embodiment of an idea of the collective’ as the authors write, for all that it is no longer public housing. Yet for Mme Moreau the changes and the enormous expenditure in Marseille, have separated it from other examples. In her opinion ‘in Nantes … they still live in the way that [Le Corbusier] suggested.’ Perhaps the authors should have visited both versions.

As Jamrozik and Kempster write in conclusion, ‘boldness and belief in architecture as a vehicle for creating a modern society’ links their four examples at a moment when the exploration of style per se becomes achingly pointless, set against ‘a broader reconsideration of the amenity of building today.’

Those who commissioned modernist houses are, and were, a particular breed. Textile designer Bernat (‘Beri’) Klein’s house, High Sunderland in the Scottish borders, was commissioned from Peter Womersley in the late 1950s. As his daughter Shelley puts it, ‘My father was the house. The house was my father.’ In The See-Through House: my father in full colour (2020) she returned after many years to care for her ageing, intransigent, father. His immediate response on her arrival was to object to her own possessions. Her wry account, and the knowledge that the house is now a deteriorating shell [1], has a resonance that these interviews, for all their insight and sensitivity, cannot match.

Julia Jamrozik and Coryn Kempster Growing up Modern, Childhoods in IconicHomes (2021) is published by Birkhauser. Copies of the publication can be purchased here.

Gillian Darley is an architectural historian who writes and broadcasts on buildings and landscapes.

Notes

- The house has been recently restored, see: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/buildings/building-study-loader-monteith-restores-peter-womersleys-high-sunderland (accessed 10.06.22)