Richard J. Neutra

EXPERIMENTAL SCHOOL, CORONA AVENUE, LOS ANGELES, 1935

‘Richard J. Neutra has carried on the Wagner tradition of experimentation in new forms, materials and methods of construction… an impetus to the intelligent solution of new problems.’

Ernestine M. Fantl on the Corona Avenue School, ‘Modern Architecture in California’ (Typescript Mimeograph, MoMA Archives, 1935)

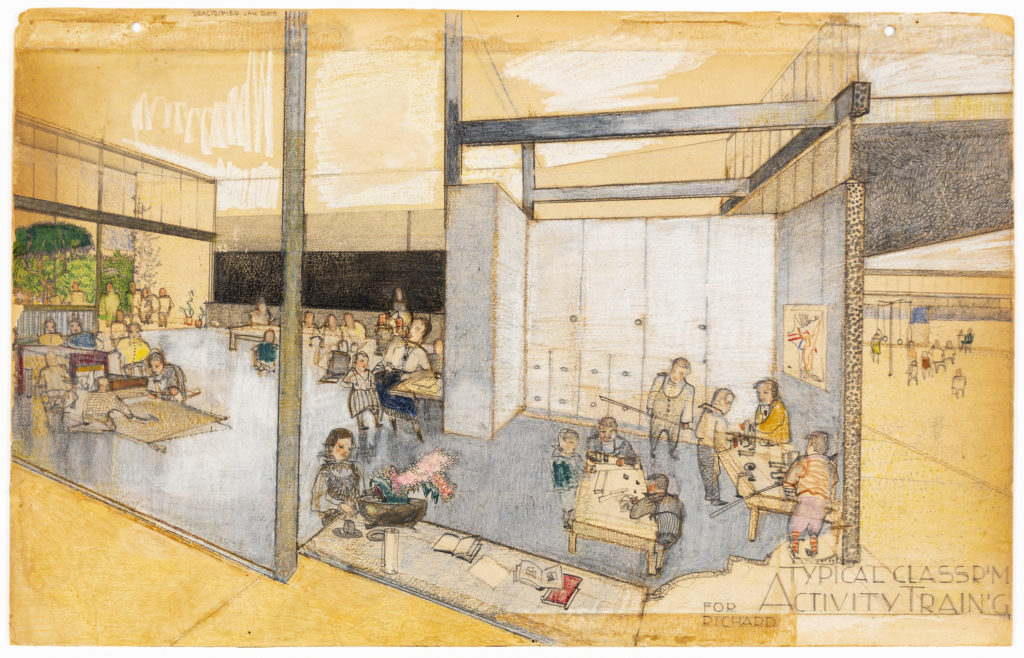

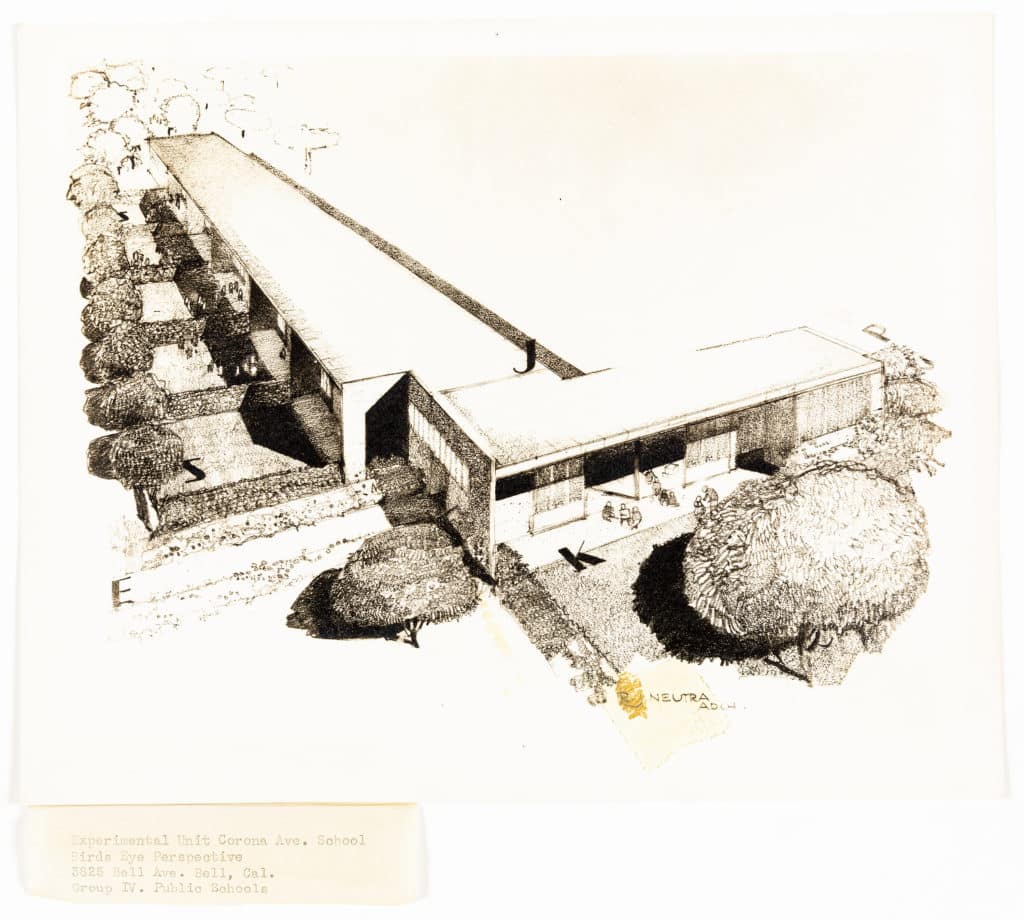

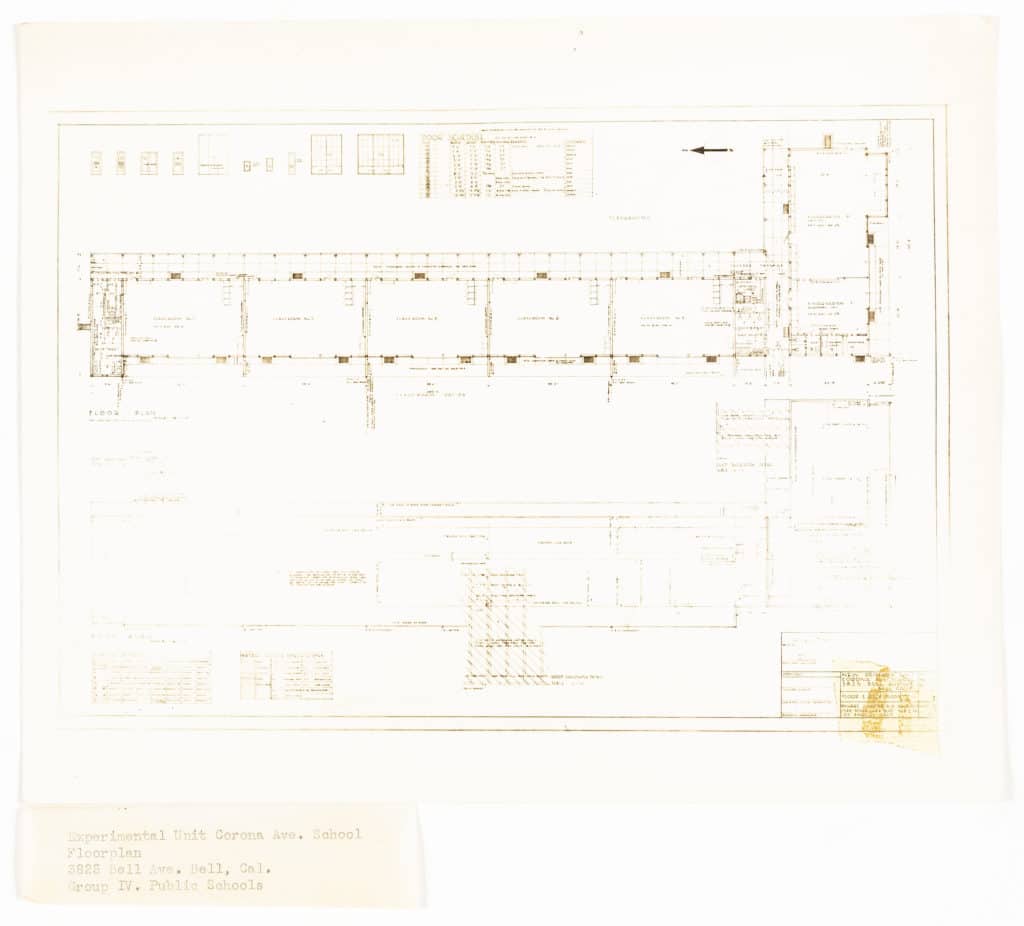

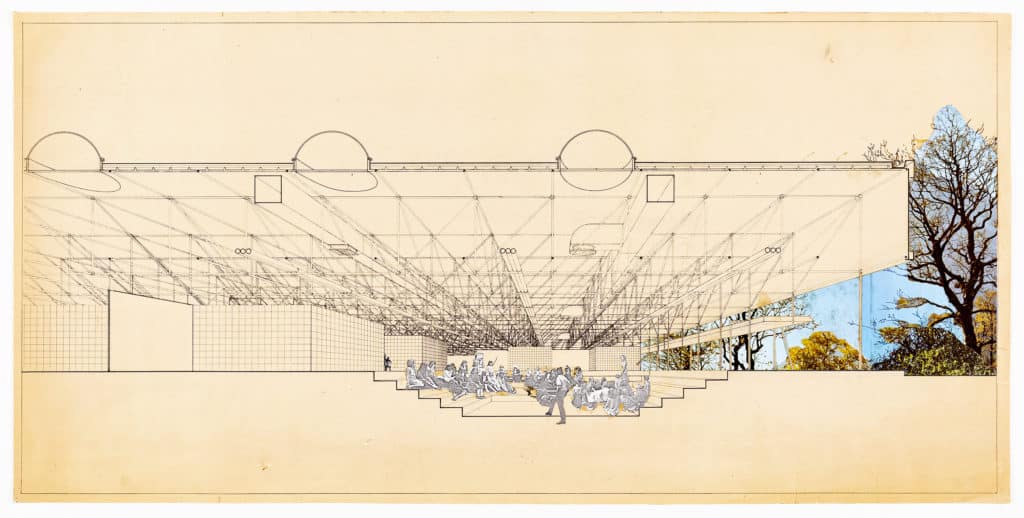

Just before 6 o’clock on an evening in March 1933, a devastating offshore earthquake, probably triggered by deep drilling for oil, struck the southern districts of Los Angeles. More than 230 schools, most built in brick and lath, and all thankfully empty at the time, were left either in ruins or in too unsettled a condition to be occupied. Within a month, an urgent programme of earthquake-resistant school building and re-building was commenced. Architects were encouraged to experiment with open plans, lightweight materials, single span construction, and low profiles. Neutra’s additions to the Corona Avenue School, among the first to be completed, took the ‘experimental’ brief much further, envisaging free forms of learning through movement and activity, establishing fluid connections between interior classroom and outdoor court, and employing a repeatable module that could be extended at will. The general perspective and plan here appear to have been exhibited in Los Angeles in 1934, showing the scheme with slight variations from the finished building, perhaps along with the remarkable pastel rendering of the concept for the typical classroom (dedicated to his precocious son Richard Raymond Neutra).

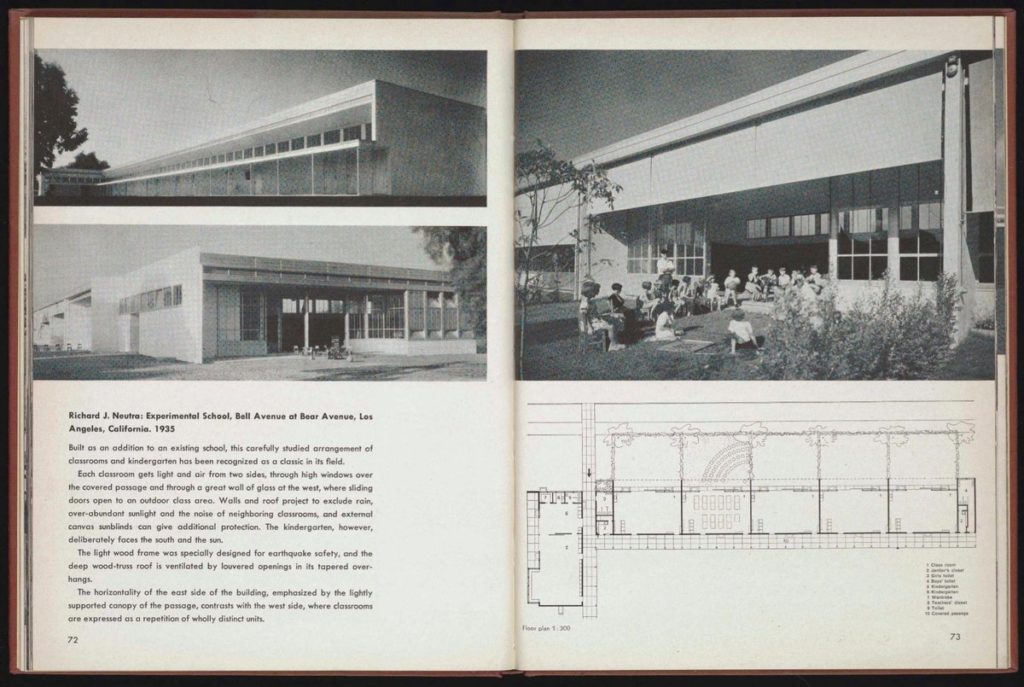

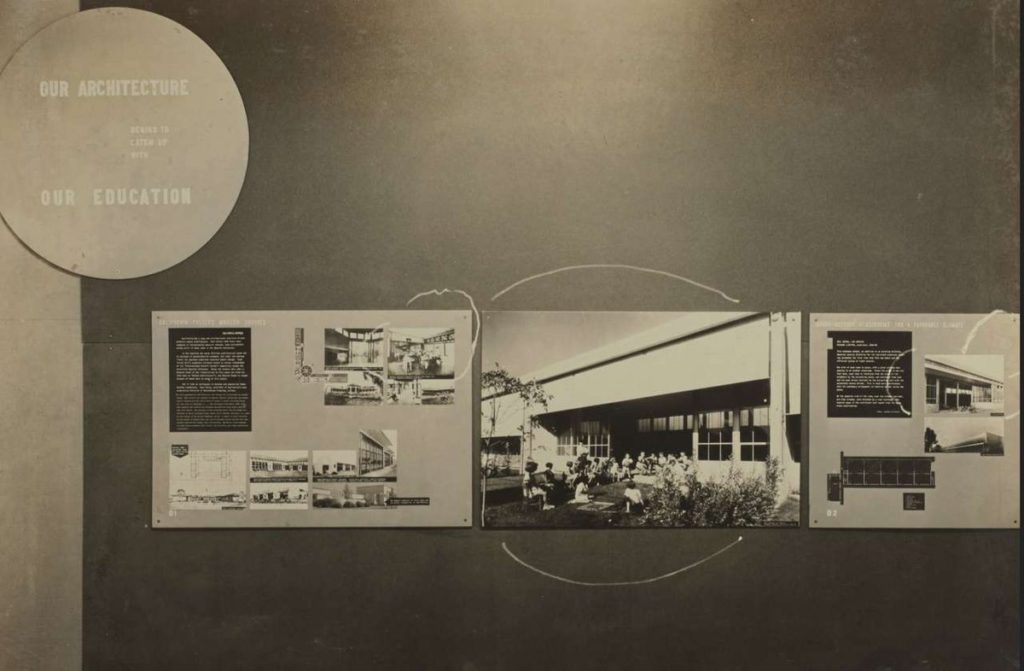

A ‘general view of the school’, probably the same general perspective, then appeared to great acclaim in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1935 exhibition of ‘Modern Architecture in California’, travelling across the country to more than 40 venues.

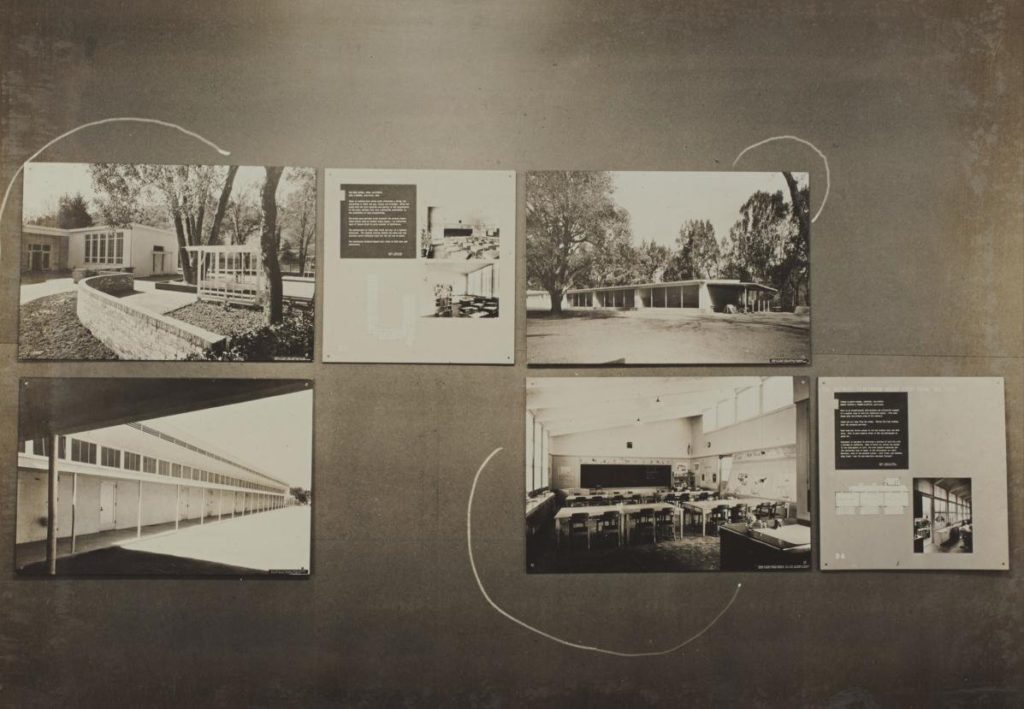

In 1942, plans and photos of the project played a central role in Elizabeth and Rudolph Mock’s panel show for MoMA on ‘Modern Architecture for the Modern School,’ which travelled to schools and community centres throughout the war to propose models of the free school for new defence communities and for the more expansive life anticipated in the postwar world. Mock’s text identified the Corona school as the first, pioneering model of an elementary school that reflected the new philosophy of child development and learning, ‘designed in relation to the child’s psychological as well as his physical needs… a place where the child can feel that he belongs, where he can move in freedom, and where he can enjoy immediate contact with the outdoors.’

The influence of these images of the school spread even further with Mock’s great MoMA show of 1944 ‘Built in the USA: since 1932,’ versions of which travelled throughout the Americas and Europe in the immediate postwar years, with an extraordinary impact on the architecture both of European reconstruction and of the developing world. By then, as the catalogue recognizes, it had become a classic example of the language of American modernism, as a model for school building on a free-flowing system, and as a demonstration of the efficiency of building along a line of repeatable but variable and spacious lightweight modules.

There are immediate and readily recognizable echoes in Giuseppe Terragni’s Asilo Sant’Elia in Como designed a year after the Corona school first appeared in print, and its fundamentals continued to resound in such works as the Smithsons’ Hunstanton School (1949–53), and in the imagination of such architects as Superstudio – not only in their school for La Spezia but in the Wagnerian notion of a continuous repetition of distinct units along a horizontal grid.

Neutra had entered architecture school in Vienna in 1910, eventually studying with Max Fabiani, Adolf Loos and others, in the deep shadow if not the direct tutelage of Otto Wagner. Though he went on to work with Erich Mendelsohn and Frank Lloyd Wright, critics and curators readily and immediately recognised the genetics of his Modernism as deriving fundamentally from the principles and methods of the Wagner school, and continued to see in his work, as it emerged on the national and international scene through the 1930s and 1940s, the most powerful American expression of Wagner’s ideas as they might be adapted to changing American conditions, and to hold up the planar language of the Corona Avenue School as its signalexample.

– Niall Hobhouse and Nicholas Olsberg