A Fragment of Wright’s Great City

Wright, Wagner and the Idea of the Great City

We become greater in service to the general effect, more harmonious as part of the whole.

– Frank Lloyd Wright, ‘To my European Co-Workers’, 1925

‘I came upon the Secession during the winter of 1910,’ Wright wrote in An Autobiography, noting with great enthusiasm the work of Klimt, Olbrich, Metzner, and above all, ‘Herr Professor Wagner, of Vienna, a great architect’. With a gracious nod to the impact of Louis Sullivan, he would go on to describe Wagner as ‘the greatest native force at the base of European modernism’. As late as his final Testament in 1957, Wright still listed Wagner, along with Berlage, van de Velde, and Loos, among the four European architects critical to the evolution of a modern language of design. The admiration was apparently mutual, students recalling Wagner’s remark – looking through Wright’s great Wasmuth portfolio of 1911, and drawing particular attention to the Larkin building and Unity Temple – that he might now pass the torch to one who could bear it better.

Though Wright says he met no architects on that first visit to Vienna, it seems highly likely that he and Wagner knew each other. This is strongly suggested by the particular though deferential terms in which Wright consistently referred to Wagner, the nature of their correspondence, and the high regard in which the fiercely anti-academic Wright held the teaching of the Wagnerschule. To give but two examples, he referred his son Lloyd directly to Wagner as a potential student in 1913 and, when engaging Richard Neutra some years later, announced that training in the Wagner stable was full and sufficient recommendation for working with him. Indeed, from 1916 into the mid-1920s, nearly all of Wright’s principal assistants – Antonin Raymond, Rudolf Schindler, Neutra, Vladimir Karfik, and Werner Moser – had trained in the broad orbit of Wagner and his followers.

In light of the studied posture of Americanism that Wright would later adopt, it is easy to forget how thoroughly he was tied to philosophical, scientific and artistic cultures grounded in the German language. He trained with the part-Swiss Louis Sullivan (who had been a student in Germany, adapted his own theory of natural geometry from the Idealists, and whom Wright famously referred to as his own ‘liebe meister’) and with Sullivan’s partner, the engineer Dankmar Adler, born in Prussia and a German-speaker from his youth. He built a collection of prints by recent German artists from the turn of the 20th century, went on to acquire a Klimt portfolio, and was so excited by the Olbrich pavilion at the St Louis Fair of 1904 that he visited twice and despatched his office to see it, too. It was a shared passion for the Romantic philosophers that brought Wright and his companion Mamah Borthwick Cheney together, and their decision to move to Europe in 1909 was motivated as much by her projected biography of Goethe (Wright’s ‘greatest German’, whose work they translated together) as by the invitation of Kuno Francke for Wright to develop a portfolio of his work with the German publisher Wasmuth. And that great portfolio bears a striking resemblance, in the manner of its illustration, in its points of view, and in its presentation, to the fourth volume of Otto Wagner’s Einige Skizzen…, which began publication in 1910.

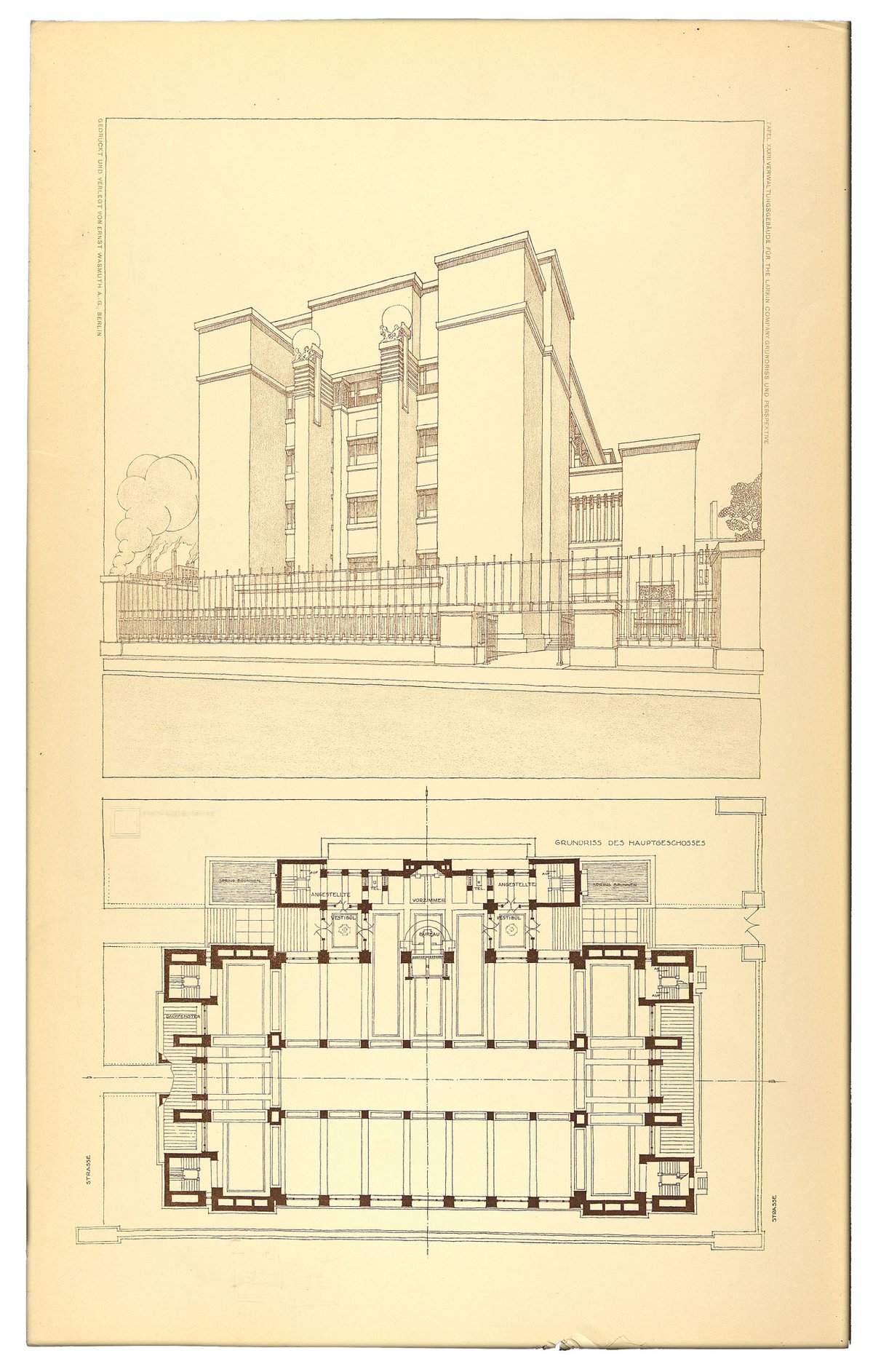

Wagner’s Grossstadt (his grand vision of how the artistry of the architect might give coherent aesthetic shape to the life of the modern city) and Wright’s Wasmuth portfolio appeared in the same year. Not only did the Wagnerschule learn from Wright’s portfolio (and from Berlage’s subsequent lectures on his work, published in German in 1912), but Wright’s work in the first years after his return to Chicago was clearly inspired by the great-city thinking of Wagner’s magnum opus. He came back to America alarmed by the chaotic development of its burgeoning cities and towns, full of the lessons he had learned in Vienna and Florence of the integration of sculpture, decoration and architectonic form, and determined, like Wagner, to discover a new universal language of space, shape and representation by employing the possibilities of new materials and structure. The result was a set of extraordinary propositions for the constituent elements of a vivid and harmonious metropolitan landscape.

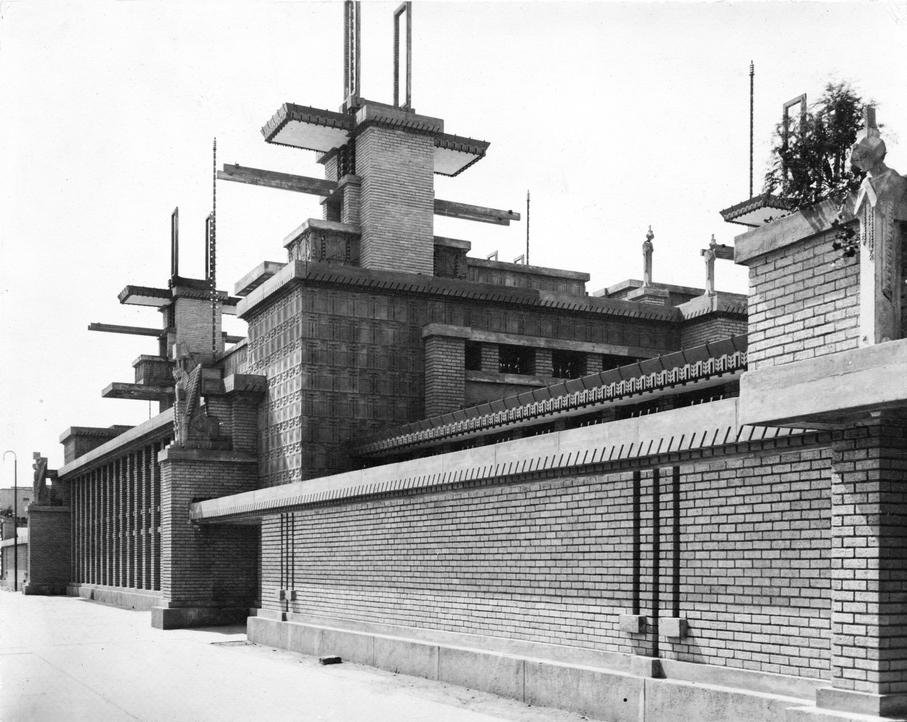

A Metropolitan Pleasure Ground

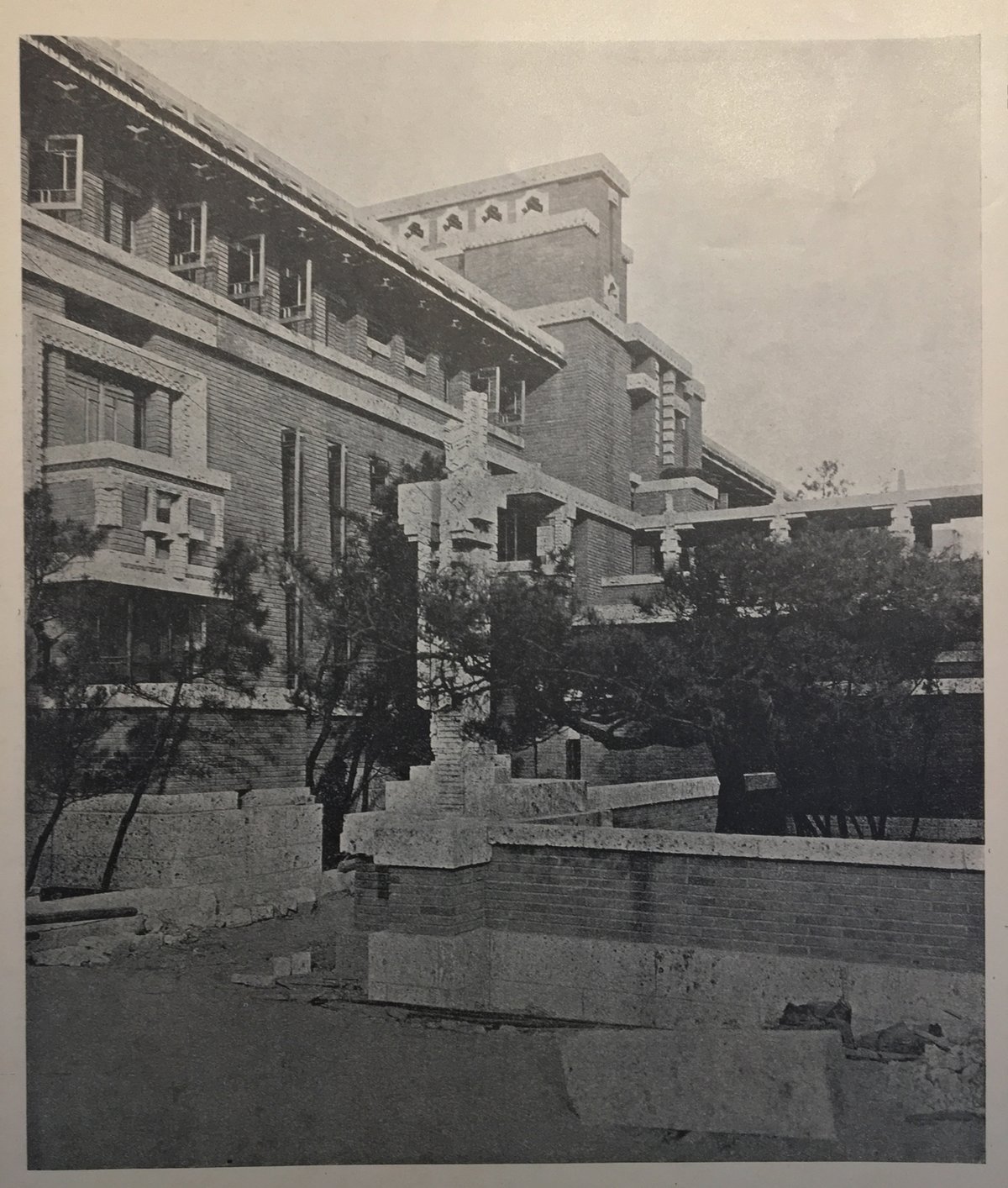

The range of urban typologies Wright addressed in these first years home is remarkable. There are unbuilt projects for a dance studio, a Chinese restaurant, a cinema, suburban rail stations, a townhouse and studio, a small bank and a small church, and a merchandise mart. Built examples include the kindergarten (or ‘little playhouse’) for Coonley, the Munkwitz garden apartments, two different ‘model city houses’ (for Bogk and Bach), and the sculpted hardscape of a garden suburb at Ravine Bluffs. Together they represent the vision of an integrated, spacious and horizontal metropolitan scheme in a new and markedly Wagnerian language. It is based on structural concrete and structured ornament, on intense articulation, on the punctuation of the cityscape through rising geometries, pylons, small towers and finials, and on a new palette of incised or inlaid surface decoration using ceramic tile or cast cement on the exterior and abstract painted figuration or sculpted bas-relief inside. Three massive projects, all starting life in 1913, constitute little cities of their own within this visionary metropole: Midway Gardens in Chicago, built in 1914; the Imperial Hotel for Tokyo, evolving over 10 years and moving from concrete to brick and tufa in the process; and the Olive Hill development in Los Angeles for Aline Barnsdall, of which only the hilltop residences were completed, its luscious street-front of theatres, studios, shops, apartments and parkland living only on paper.

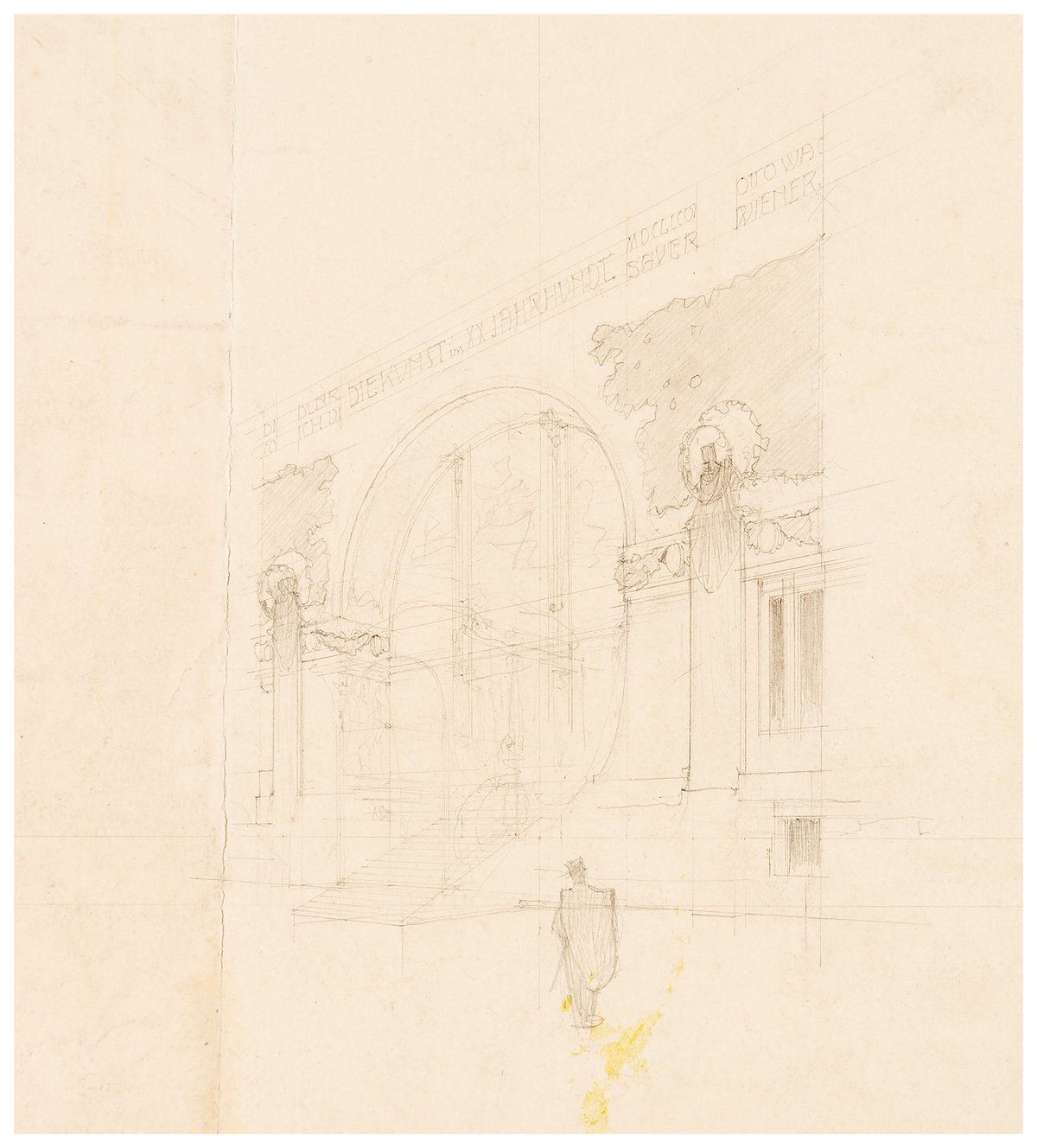

Wright presented the first elements in this vision of a new city in his Art Institute exhibition of April 1914. Chicago – now in love with its own skyward train of thought – was variously baffled, shocked, or simply indifferent. But Europe somehow noticed, and it was these radically expressive city works that formed the core of Wright’s ‘Life Work’, as he presented it – glancing lightly over the essential precedents of his Prairie Years – in the seven special issues of the Dutch magazine Wendingen in 1925. They constitute 100 of its 162 pages, with almost half of the entire series devoted to its three great landmarks: Midway Gardens, Imperial Hotel and Olive Hill. Each is shown, in a startling departure from the Wasmuth portfolio, through an extraordinary emphasis on the sculptural, their details and decorative elements, and on views incident to the eye on passage rather than through the general perspective.

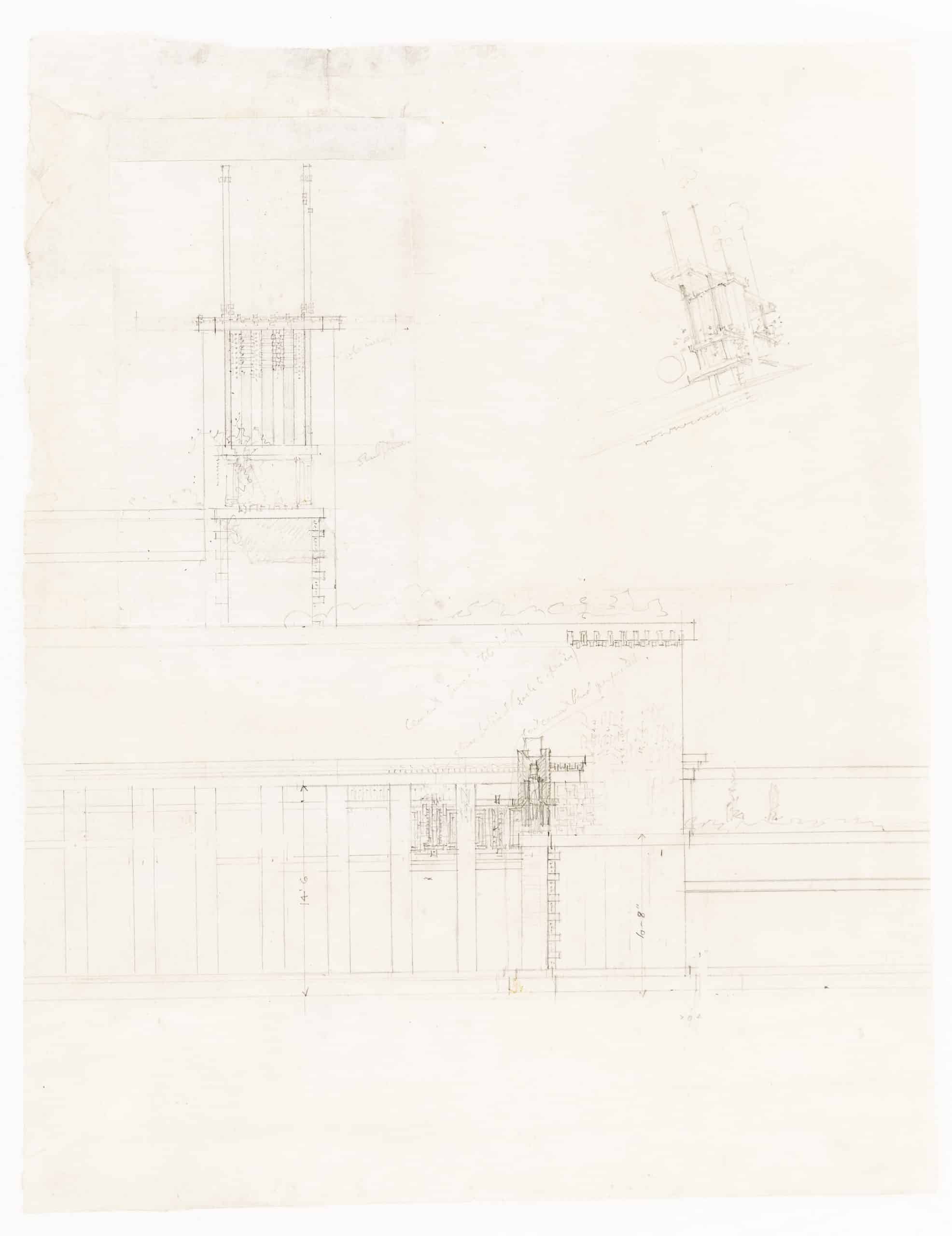

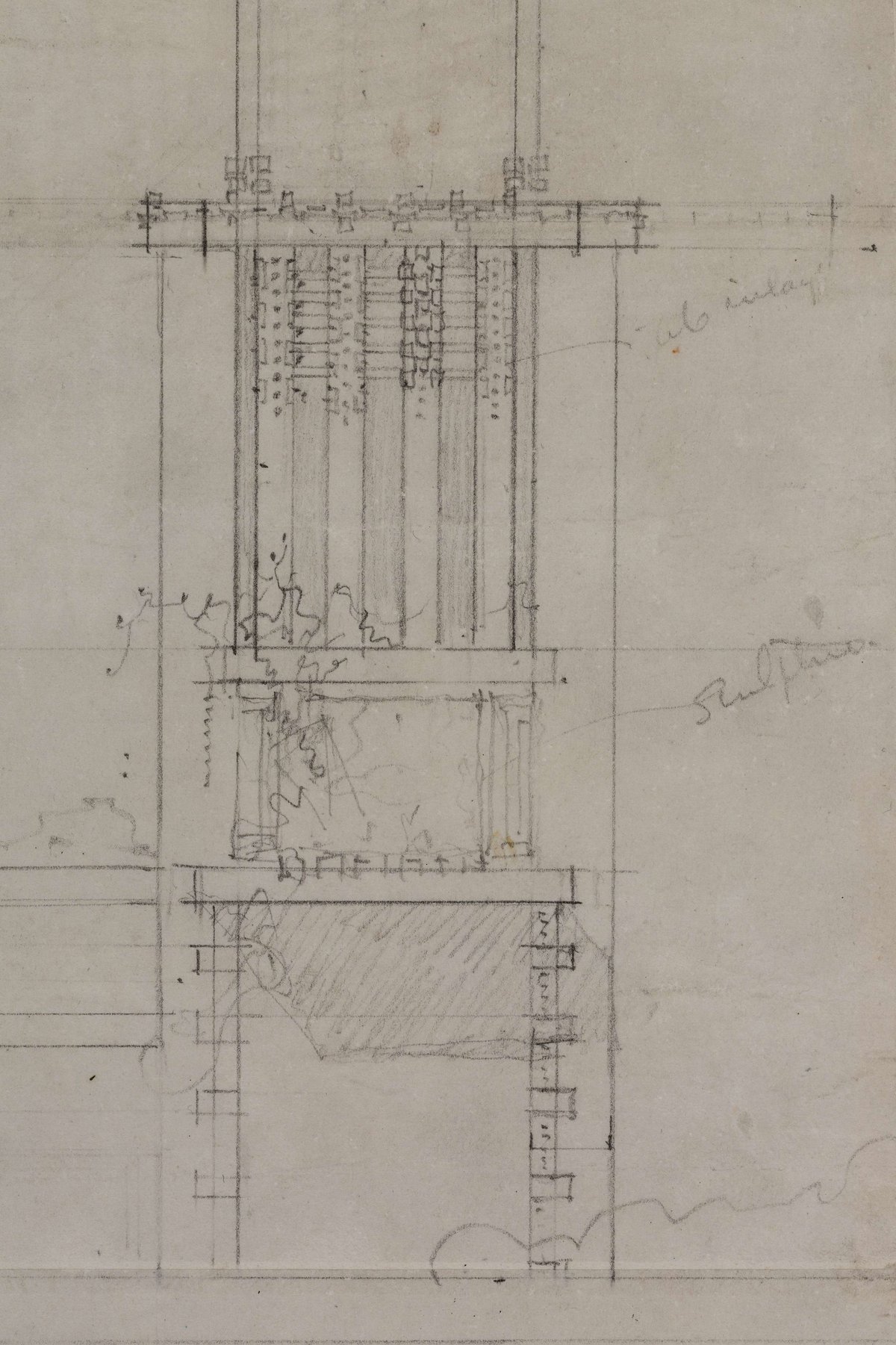

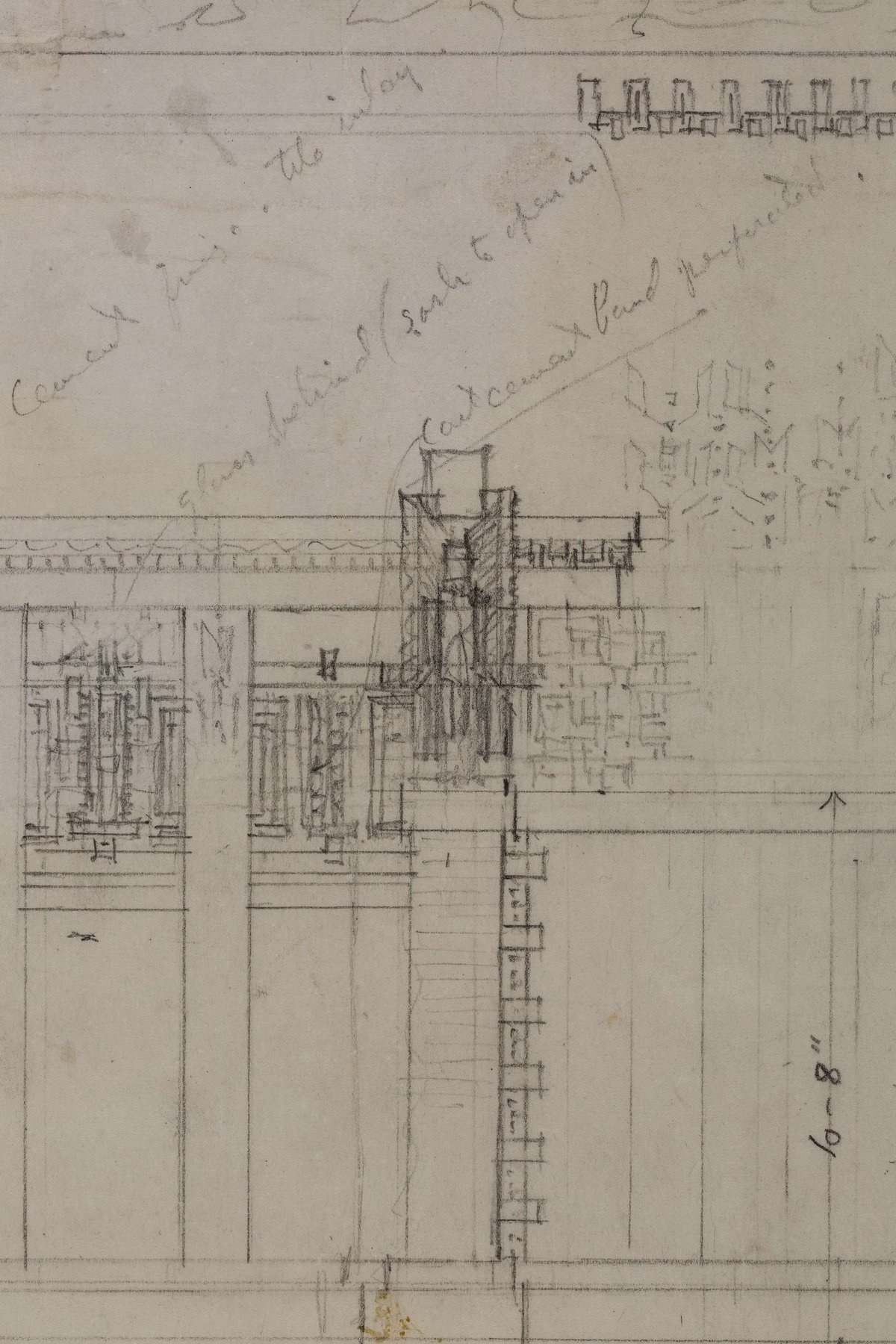

In this sheet of pencil studies for Midway Gardens we see, largely in his own hand, Wright’s intense re-workings of those particulars – the placement, function, materiality and effect of the details that will catch the eye and make sense of a complex whole. The project was an elaborate combination – on what had until recently been the southern edge of Chicago – of outdoor theatre, symphony hall, cafés, restaurants, palais de dance, clubs, cabarets, gallery promenades and hanging gardens. The whole venture – first appearing in drawings as a ‘Concert Garden’ in the spring of 1913 – was always an uncertain and changing proposition, and it had begun to fail even before Prohibition sounded its death-knell in 1919. But in order for its investors to begin to recoup initial costs it had to appear in time for a summer season the following year, and there were extraordinary demands on Wright and his office to produce designs for a new building type largely in the new material of concrete block reinforced with metal bars. Wright makes it clear that he was looking to evoke a sense of fancy, vitality and gaiety, and he used both sculptures and incised or extruded patterns throughout to catch light and animate space and surface. As a result hardly a moment of surface was left plain, and the investigation of each detail was exhaustive.

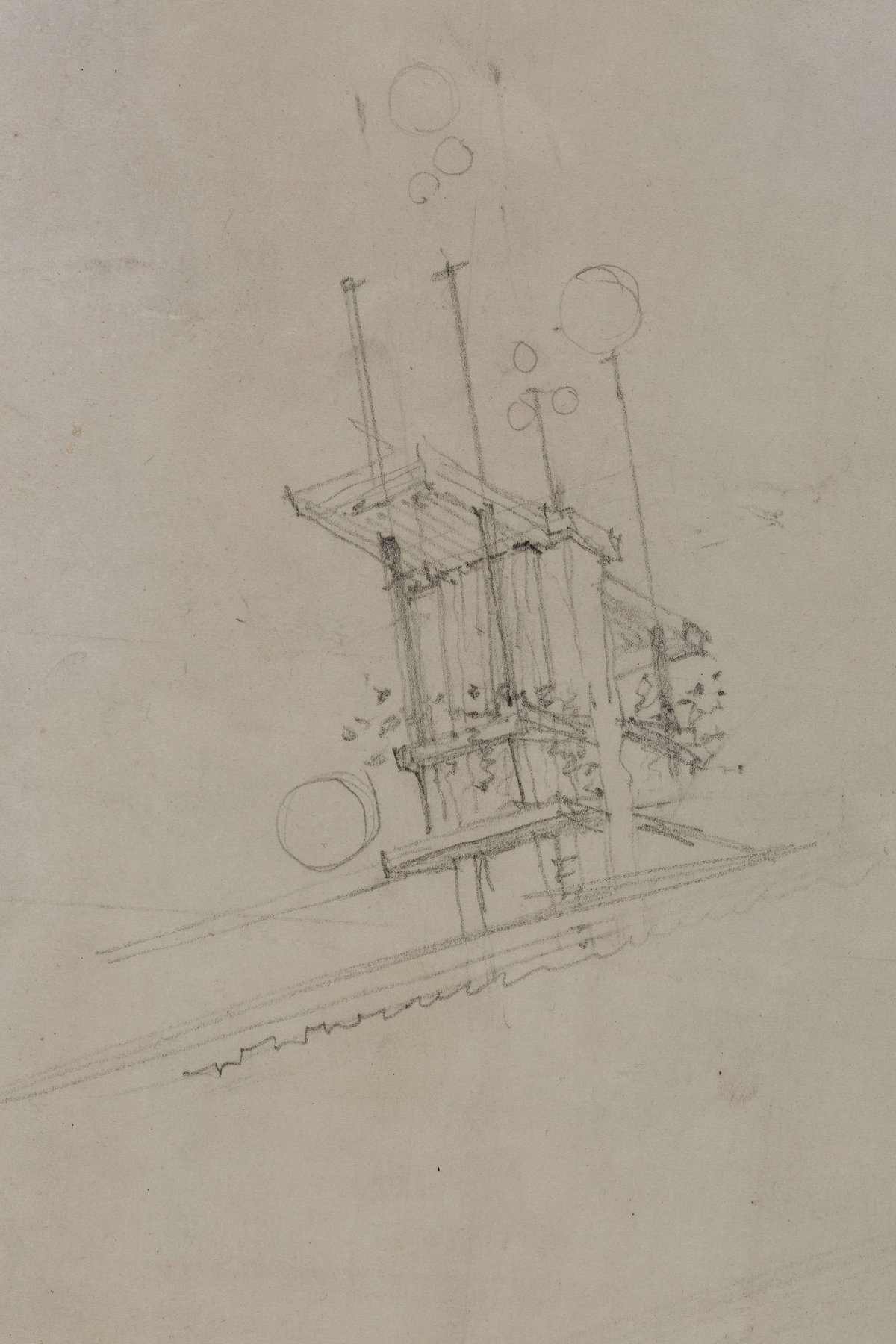

The principal architectural element was the ‘winter garden’, essentially a closed shell for performance that would screen the huge inner courtyard from the thoroughfare to the south and would present, with its two flanking ‘belvederes’, a principal façade to the street. The three parts to this sheet are all concerned with ways to enliven and frame that low blank shell, and to signal this place of entertainment on the outer city skyline, where traffic moved at speed. On the upper left is an elevation of one of many variants examined for the four matching observation towers above the winter garden, probably as it would be seen from the open courtyard to the north. The version here is close to the simplified form of the towers as they appear in some of the earliest presentations. The drawing has apparently been cut and inserted from a separate sheet, or removed from another sector of this sheet (which has itself been torn from a larger whole) and repositioned. On the upper-right is a rougher perspective sketch at a much smaller scale of a second variant, closer to the shape of the towers as they were finally erected some months after the opening of Midway in June 1914 (at a point when Wright, after the tragedy at Taliesin in August, had passed much of the final work on the project to others in his office). The third drawing, at yet another scale, looks at the patterns and materials for the decoration of the eastern segment of the front, or south, façade, including one of the spirits raising the fundamental forms of architecture – in this case the cube – that were to appear at a number of points in the project. This is essentially a study of the project as built. The placement of the drawing of the tower above – though at a larger scale, not positioned quite as it would appear, and showing its adjacency to elements that neither match the scheme as built nor relate to the same façade – seems intended nevertheless to suggest the relationship between the two elements.

The City Imperial

This leaves us with a sheet that is close to a collage, and something of a puzzle. Perhaps the mystery might be solved by considering its provenance, and by noting the very unusual presence of notes on materials and the addition of sketch diagrams of pattern geometry: ‘Cement frieze… tile inlay… Cast cement Band perforated… Sculpture.’ At some point the sheet passed to Wright’s son David, who received it rolled on a scroll and housed in a Japanese print box, and who referred to it as a sheet of studies for the Imperial Hotel. The Imperial Hotel was not just a hotel but in effect the Emperor’s guest house for foreigners: an urban resort, a symbol of modernity, and (by decree) a dedicated meeting ground for the Japanese to do business with the West – its gardens, terraces and public rooms being as important as its accommodations for residents.

We know that Wright, when presenting ideas for the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo in early in 1917, took with him and exhibited there drawings of concrete blocks and decoration, and that the Japanese had analysed and approved the suitability of concrete to the local climate as early as 1913. Early studies for the Imperial actually show towers not unlike that in the elevation here, and above a rather similar adjacent structure. Noting this, and the erasures of certain lines, it might even be possible that Wright has in fact adapted a Midway study to fit more closely his ideas for the Imperial. At all events, it seems at least reasonable to think that Wright put together this assembly of drawings to demonstrate a decorative and material approach to the Imperial Hotel – a most unusual use of study sketches – and that, with his hand and design spirit so powerfully and delicately present, he later valued it enough not to return it to his archive but to make of it a gift to his son.

– Esther McCoy