Poetry and Architecture (2023) — Review

The concluding section of Hegel’s Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics considers ‘the general types of art’ that constitute the self-unfolding of ‘the Ideal, as the true Idea of beauty’, and ranks them in ascending order: architecture, sculpture, painting, music, poetry. Poetry (dependent upon sensuous manifestation, so not yet philosophy) is made the apex of this schema ‘because the artistic imagination [Phantasie] is its proper medium, and imagination is essential to every product that belongs to the beautiful’[1]. We needn’t indulge Hegel’s principle of human or divine freedom self-realising the absolute Idea to recognise that the exhibition, Poetry and Architecture, conceived and curated by Fabio Barry at Hay Castle, seeks to place together the lowest and uppermost levels of Hegel’s schema. Acknowledgement of this intent serves as a starting point for the following discussion, which includes analysis of works in the exhibition.

Dalibor Vesely preserves something of this schema but replaces Hegel’s characterisation of architecture as the least-complete manifestation of the Ideal. For him, architecture is the most-fundamental to culture (architecture as mother of the arts), ‘architecture represents the most elementary mode of embodiment that enables the more articulated levels of culture, including numbers and ideas, to be situated in reality as a whole’[2]. In fact, Vesely’s use of the term ‘embodiment’, which most contemporary readers will associate with the work of Merleau-Ponty, points to the ancient tradition by which the organisation of material things — ‘nature’ — enables recognition of phenomena associated with human mental powers — ‘culture’ — such as spirit, imagination, truth, and beauty. (An example is Heidegger’s reworking of the Aristotelian physis and nomos [nature and culture] as the strife of earth and world)[3].

The priority attached to what Vesely calls ‘the more articulated levels of culture’ is already present in the Socratic notion that the soul has a more perfect apprehension of what is constant, universal, essential (the ‘forms’) than do the senses of the changing, imperfect body[4]. However, it is the Christian development of John 1:14 (‘and the Word became flesh’) that elevates the Latin incarnatus (lit: enfleshment, embodiment) to a principle which grants insight into transcendent Being[5]. John of Damascus defeated the Iconoclasts by appealing to the Incarnation, which he then made into a general characteristic of understanding. Commenting on Dionysos Areopagita’s Divine Hierarchies, John declares[6]:

‘We supply by the variety of sensible symbols the visible order, which is according to our own measure. Those sensible symbols lead us naturally to intellectual conception, to God and His divine attributes. Spiritual minds form their own spiritual conceptions, but we are led to the divine vision by sensible images.’

The last phrase anticipates by three centuries the more familiar lines from Abbot Suger’s verse inscription over the door to the abbey of St. Denis (De administratione, XXVII):

‘The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material

And, in seeing this light, is resurrected from its former submersion.’

Here, indebted to Neoplatonism, we find ourselves within the reality-as-representation known as the Great Chain of Being, the ghost of whose hierarchy of the sensible and the intelligible survives in Hegel’s schema of the arts. In other words, embodiment was invented to resolve the problem of meaning, and seems to have retained its character of a vertically stratified continuity of differences since Plato.

Embodiment still serves this purpose, recast as cognition (or perception), involving, for example, bodily motility between gesture and language[7]. Secularisation has dissolved the symbolic hierarchy, although the sensitivity to ontological levels remains, as in Vesely’s notion, above, that the embodying conditions of architecture support the more articulate strata of culture, not the other way round. Persisting alongside this development is the ancient reciprocity of things and thought (nature and culture) that underpins iconography, but also, in the current understanding, suggests that we acknowledge extended topographies of embodiment. Moreover, our involvements in the claims and affordances of these deep topographies are fundamentally metaphoric, the phenomenon which underlies the famous dictum from the Ars Poetica of Horace: ut pictura poesis, as is painting so is poetry (also, incidentally, collapsing two of Hegel’s levels)[8,9].

Barry eloquently developed the analogic universe available to Ancient Near Eastern and European cultures prior to the collapse of the symbolic hierarchy in his book, Painting in Stone: Architecture and the Poetics of Marble from Antiquity to the Enlightenment (2020). The word ‘poetics’ in his title does not come from the centuries of writing he cites by priests, princes, artists, architects, or authors (of ekphrases, texts, hymns, prayers or poems), largely because these cultures inhabited a cosmos held together by analogy, for which poetry was a specific genre. Accordingly, Barry, drawing upon Bachelard, resorts to the notion of poesie developed by the Jena Romantics. Poesie absorbed poetry along with the other arts as well as nature (endowed with a soul) into a fundamental creative principle. So, for example, Coleridge, an avid student of Schelling, sought to identify the inspired artist with natura naturans (the creative power of nature, generally accorded to God, as distinct from natura naturata, the things created by nature)[10]. The radically expanded analogic field comprising poesie was acquired at the expense of the depth afforded by the symbolic hierarchy, for which early substitutes were found in motifs like emotional intensity and the sublime (combined in Rudolf Otto’s Idea of the Holy). Although the arts are no longer regarded as the basis for a cultural ethos as they were for the Romantics, this generalised creativity still governs what is conventionally meant by poetics. The promise of artistic freedom obliges any specific work to account for its situatedness in a culture. Such acts of justification themselves appear within a possible spectrum from philosophy or theory to sheer vivid performance (as with rap), implying, in turn, the familiar fragmentation of constituencies and criteria for ‘good’ art (by contrast to, for example, communal ritual or the original performances of Greek tragedies). Indeed, the composition of fragments has characterised artistic production for well over a century.

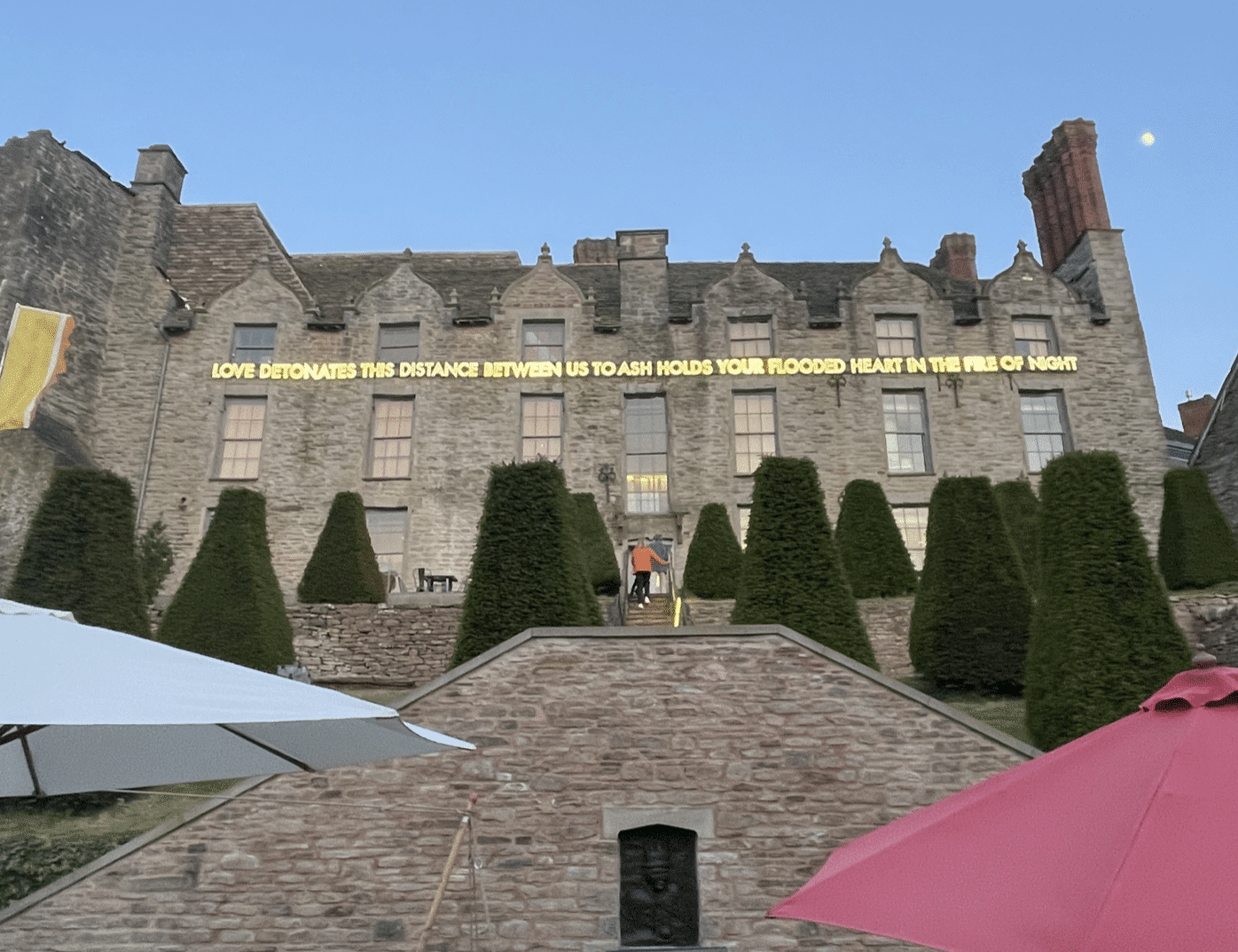

It is in this context, where ‘multimedia’ now tends to imply augmented reality (corresponding to a universe deemed to ‘compute’ information) rather than, for example, Byzantine liturgy, that Barry orchestrates the dialogue between architecture and poetry as a landscape proposition in the installation of Poetry and Architecture. Barry, who trained as an architect, worked with Tom True, Executive Director of Hay Castle, to make an exhibition that responds with sensitivity to the castle’s position on the hill above the town within the Wye Valley, as well as to the architecture of the ruined and rebuilt castle. The castle remains consist of a 12th century fortification tower and a Jacobean wing which, as one ascends the hill and nears the fabric, transform from a distant relic of seigneurial rulership into a vertical garden of stones bruised by history. Stretching the length of the Jacobean wing, visible across the valley and facing the town are Robert Montgomery’s luminous letters reading LOVE DETONATES THE DISTANCE BETWEEN US TO ASH HOLDS YOUR FLOODED HEART IN THE FIRE OF NIGHT. Positioned just beneath the seven dormer windows of the Jacobean range, the installation establishes an upper horizon for the deep entry sequence to the site. This authority is qualified in its realisation by the hundreds of little lightbulbs outlining each letter and evoking the quaint enthusiasm of fairground signs. It is the wry smile of a child on the wizened face of a stony ancestor.

This dual personality is echoed in Montgomery’s words, which seem at once to be both an announcement from God or the civic authorities and an entirely private reflection, and where LOVE might be the subject of both phrases and ASH both the end of the first phrase and the beginning of the second. The confrontation of love and a conflagration resonates with the several fires which have afflicted the castle. As one ascends through the austere lithic atrium of MICA Architects’ recent renovation, the nominally political message installed on the mezzanine of Montgomery’s again luminous ALL PALACES ARE TEMPORARY PALACES takes on local readings. The phrase can be read as an autobiography of the castle, possibly suggesting that its current use as a ‘centre for arts, literature and learning,’ as well as a venue for parties and weddings, makes it a version of a people’s palace[11]. This reflects Barry’s observation in his notes for the exhibition that poets have regularly asserted, since Middle-Kingdom Egypt, that their verses would ‘outlast earthly monuments’. More generally, the thematics of dwelling (in love, in reverie, in rulership or ownership, in the land or in history) and fire (of ardour, of inspiration, of destruction) open broader and deeper speculations regarding transience, ruin and renewal. All this is consistent with a poetics that, like the windows in the stone walls of the castle, creates ruptures within a chthonic topography that open to potential references, evoking the original conditions for possible expression or communication or orientation and, as it happens, echoing Le Corbusier’s summary of the chapel at Ronchamp, ‘word addressed to place’[12].

The lithic ascent concludes in the attic of the Jacobean range (at the horizon marked by Montgomery’s LOVE-ASH sign) where one arrives in a stone-sheathed room with a board floor housing three elegant wooden models from Niall McLaughlin Architects (for the Cafe-Bar, Deal Pier, for the Bishop Edward King Chapel, Cuddesdon and for the International Rugby Experience building in Limerick). Each is exhibited together with a poem whose relatedness to the buildings McLaughlin described as parallel modes of dwelling, so sharing a common ethos rather than, as it were, illustrating each other. The formulation recalls Heidegger’s lecture based on a fragment of Hölderlin, ‘…Poetically Man Dwells…’, where the measure of human finitude ‘on the earth’ and ‘beneath the sky’ is made the basis for ‘poetry as the authentic gauging of the dimension of dwelling … the primal form of building. Poetry first of all admits dwelling into its very nature, its presencing being. Poetry is the original admission of dwelling’[13]. This is not the Hegelian primacy of poetry as an art, nor is dwelling necessarily architecture (although always redolent of earth). Rather, Heidegger seeks to understand how we make (the Greek poiesis) fruitful conditions of situatedness in the play or strife of the natural conditions and language (earth and world), such that ‘the same gathers what is distinct [difference] into an original being-at-one’.

This idea of the ‘one’ (‘being-at-one’) implies a common-to-all, which current preoccupations inhibit being discovered. In the lecture, Heidegger intends ‘measure’ in the sense used by John of Damascus, and he equates it with ‘dwelling’ as the ‘span’ that brings together earth and heaven, whereby the mediation of ‘span’ characterises the making of situatedness. Although Heidegger seeks to suppress the quantifiable or literal aspects of ‘dimension’ or ‘measure’, there are aspects of McLaughlin’s architecture that alert us to how the practical application of measures is rooted in metaphoric meanings. These help to elucidate our place in the tension between earth and heaven common to dwelling and poetry — also expressed as sameness/difference, proximity/distance, intimacy/grandeur, horizontal/vertical, regular/irregular, fittingness/awkwardness, delicate/rough, brevity/longevity, but also including such general phenomena as harmony and, above all, rhythm, which is fundamental to life’s myriad cycles. Measure rarely asserts itself as an explicit topic in either dwelling or poetry; rather it is manifest as an attitude of care and depth of understanding, discretely qualifying relationships of content.

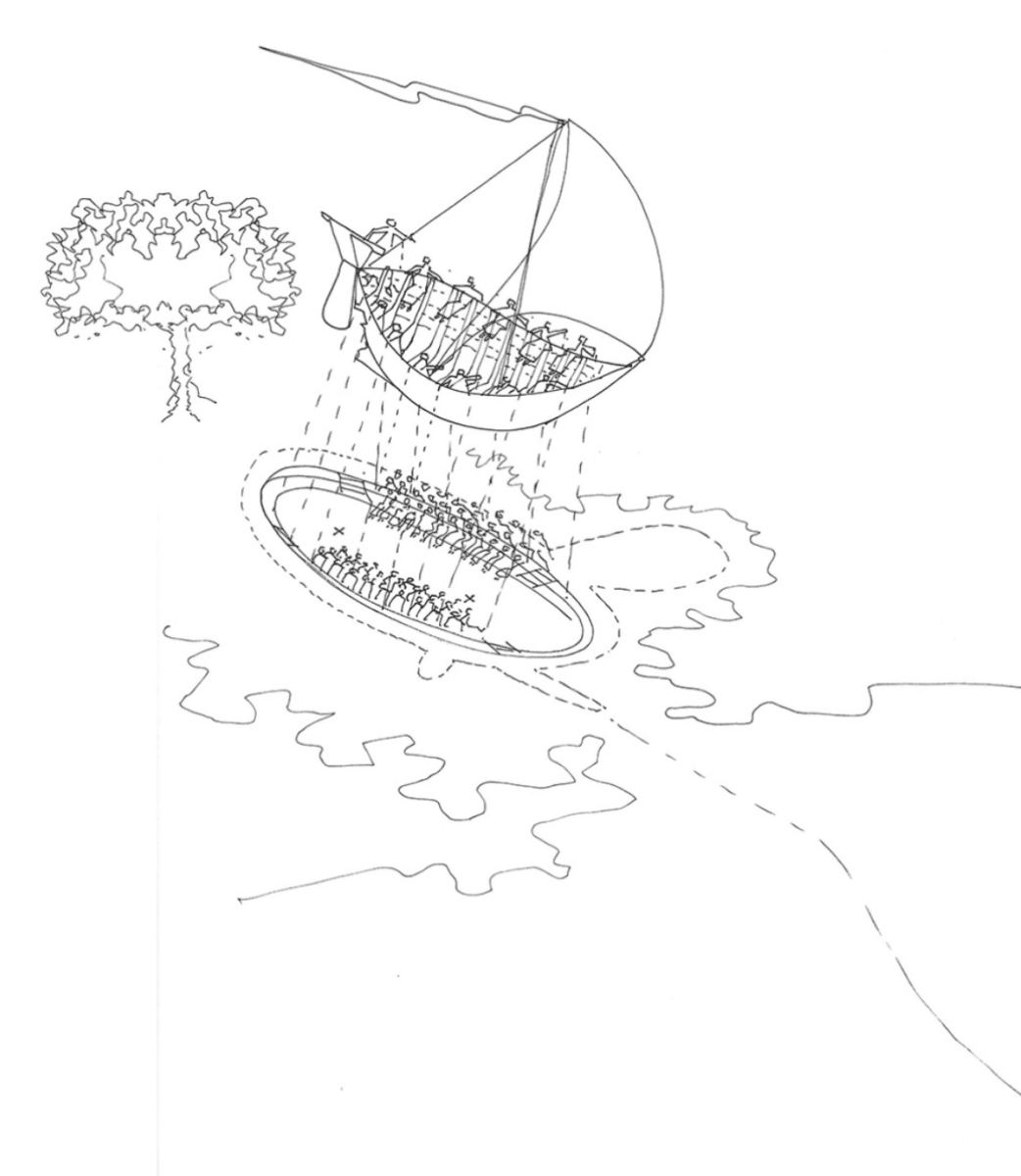

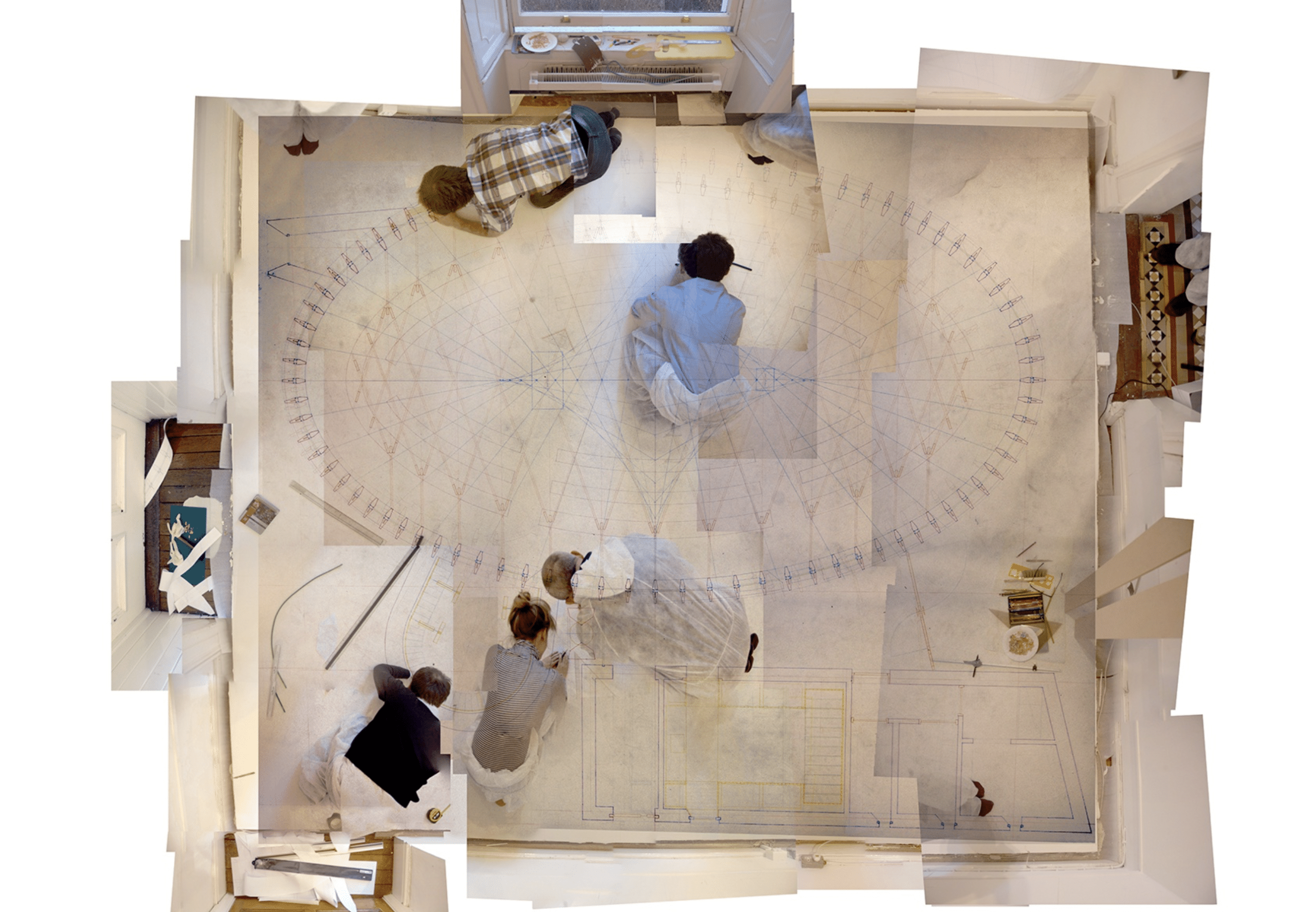

People embody these nuances of measure when performing rite, ceremony or dance, as did the executors of McLaughlin’s remarkable Tracing Floor drawing of the Bishop Edward King Chapel. Indeed, the elliptical Chapel — neo-Gothic, refracted through Rudolph Schwarz — eloquently embodies Heidegger’s argument. This is in part because it successfully interprets a Christian chapel and is consequently oriented to a ‘one’ with a two-millennium tradition. Heidegger spoke of poetry as a principle, presumably intending good poetry (though he favoured the Romantics); but Seamus Heany’s Lightenings VIII, with which McLaughlin affiliates the Chapel, wittily subjects Heideggerian mediation to a rupture between heaven and earth, since its flying ship with a dangling anchor can only continue its heavenly journey if released from the altar-rail — made a sign of human suffering (finitude) — as if to separate not only the saved from the damned but also the nave from the chancel[14].

Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space appeared seven years after Heidegger’s lecture, of which Bachelard makes no mention, although it is possible to detect a similar direction insofar as Bachelard speaks of ‘poetic image’ which ‘reverberate’ (Minkowski) within ‘an ontology’. To this end, Bachelard memorably contrasted the irrational cellar (into which one must bring a light) with the rational attic articulated by the geometry of the roof-trusses (an ancient preoccupation of French architecture)[15]. The renovation of Hay Castle by MICA Architects conforms to this paradigm. A large gallery is created to provide exhibition walls beneath the profiles of the dormer windows, furnished with museum lighting. This is the characteristic Enlightenment setting for critical reflection. The ostensibly neutral background for signifying objects is an important constituent of Barry’s installation in this room, which concerns the spatial distribution of poetic words, phrases, and stanzas. It is an artefact of our alphabet that letters stand forth from their background by comparison to, for example, the calligraphic tradition of Islamic script, which more readily participates in ornamental frameworks. Another, even more elaborate case, is that of Mayan hieroglyphs, whose images not only carry meanings and grammar but also appear in myths painted on pots, in statuary, embedded in regalia, figured in the architecture. These images incorporate the Mayan ecology of celestial events, caves, animals, plants, utensils, foods, wars and religion to create living hieroglyphic topographies, thus radically compacting the Western earth-world distinction. In the gallery installation, the white of the page for poetry veers between substantial materiality and its opposite, the modernist void of space. Two works of architecture that support inscriptions confront each other across the long dimension of the room, whilst examples of concrete poetry occupy the two ends.

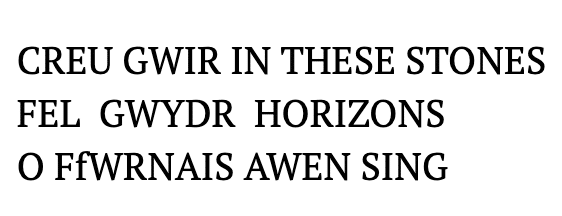

One of these works of architecture is the facade of Jonathan Adams’ Wales Millennium Centre, Cardiff, where the commitment to language and land (world and earth) redolent of Romanticism’s Northern European Celtic Revival results in storey-high window-letters in Welsh and English incised through the copper fascia. Glowing across Cardiff Bay at night, the solemn monumentality is relieved by the wit of Gwyneth Lewis’ arrangement of the words, which allows the Welsh and English portions to be read as two separate languages (in two columns) or one bilingual tongue (in continuous lines):

The English portion sets the Welsh devotion to singing within a familiar trope regarding architecture and music, the latter alluding to celestial harmony with horizons. The Welsh portion (trans.: ‘Creating truth / like glass / from Inspiration’s furnace’) not only allows both stone and glass horizons (when read together with the English) but the copper of the building’s dome and fascia also led Lewis to combine Welsh industry with the cauldron of Caridwen[16].

Caridwen was the sorceress or pagan goddess of medieval Welsh poetry who, after some shape-shifting, consumed and then gave [re]birth to the beautiful and gifted child who became the mid sixth-century Taliesin (tal – ‘gable’ or ‘brow’ – iesin – ‘radiant’, ‘shining’) Ben Beirdd (‘Taliesin, Chief of Bards’). Although poesie is more of a concept than is awen, with its heritage that is at once historical, legendary and symbolic (from the transition to Christianity), they evidently share a concern to participate in the creative power able to disclose the richness and profundity (the Heideggerian span) of a reality that mediates chthonic death and renewal with celestial eternity[17].

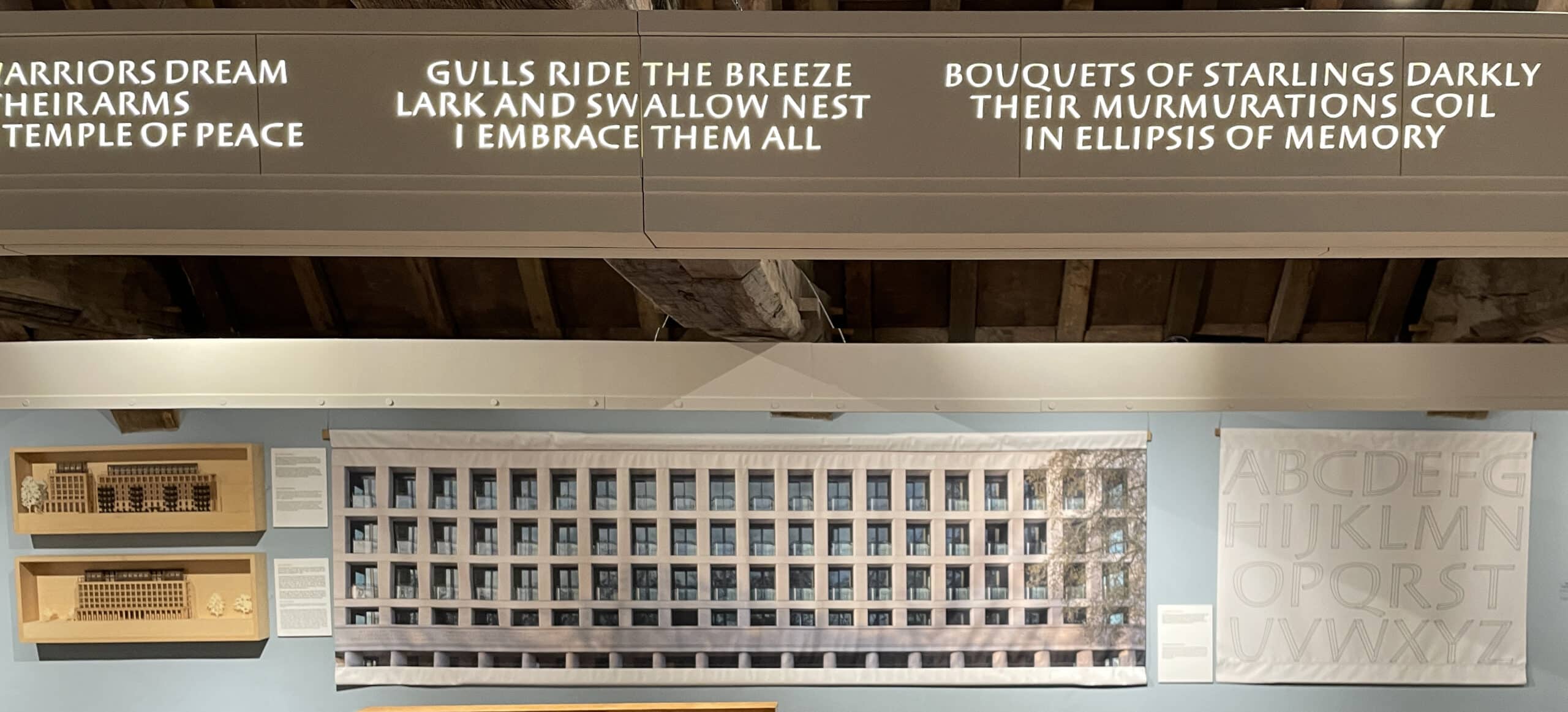

Indeed, Pelé Cox speaks of just such magical inspiration as the forty stanzas fell into place for the inscription carved into the frieze ringing Eric Parry’s residential building that overlooks the Thames and the gardens of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea. Now called 1 Grenadier Gardens, the building is part of an urban intervention replacing the demolished Chelsea Barracks, and Parry’s concern to preserve the local typology and street pattern revives an ancient dialogue between city and garden, which Cox develops in her poem. Several models and drawings in the gallery show that the refined muscularity of Parry’s limestone facade harbours in its depth voluptuous bowed glass balustrades whose railings might be snakes, vines or two hands reaching for each other. Coordinating her three-line stanzas with the rhythmic measure of the facade, Cox responds to the latent figuration by evoking the site’s rich history of gardens. Accordingly, the four stanzas on the west facade refer to the curative herbs and plants of the Chelsea Physic Garden whilst those on the east facade refer to the eighteenth-century Ranelagh Pleasure Garden. The longer, eleven stanza south and north facades are more generally mythic, involving the city and the river, the sun and moon as well as the Green Man and Gilgamesh, whose epic bears comparison with the slightly later story of Eden, insofar as both involve paradigmatic humans, nature, gods, mortality, sexuality (which is beneficent in Gilgamesh and a curse in Eden), and city-founding (heroic for Gilgamesh, the result of a fratricide in Genesis). The play of rhythms (of facade, of poem) becomes a play of temporalities (seasonal, mythic, historical, performative) by the manner in which the poem was composed. Cox titles the poem Cento, which is Latin for ‘patchwork’ and refers to a late Classical form of poem, revived in the fifteenth century, composed of lines from earlier poems. The range of works on which Cox has drawn stretches from Ancient Near Eastern through Classical, Anglo-Saxon, and Romantic sources up to Eliot’s Wasteland. The remarkably seamless continuity in the result is, moreover, itself put in motion by the manner of its incision into the limestone, where the drift of shadows animates the beautiful letters by Tom Perkins and progressively exposes passages of the poem to light. This is made more apparent by its disposition as a horizontal frieze instead of the customary columns of text. This allows them to be read as three-line stanzas, but also encourages discovery of opportunistic horizontal and vertical clusters, introducing a tension between potential chaotic incomprehension and the creativity of new insights, depending upon the reader’s imagination. This as can be seen in the extract below from the south facade, spoken like foliage from the mouth of the Green Man, recalling the Chelsea Pensioners and the Thames:

The parade of relational clusters recalls that of the Parthenon frieze, and one acknowledges that Cox’s poem Cento hosts its verses like the building its residents. This effect is enhanced by the need to circumambulate its four-quartered structure, which is re-enacted in the Hay Castle Gallery in the form of a CNC-milled halo with luminous letters suspended from the ceiling. This completes the horizon announced by Montgomery’s LOVE-ASH sign.

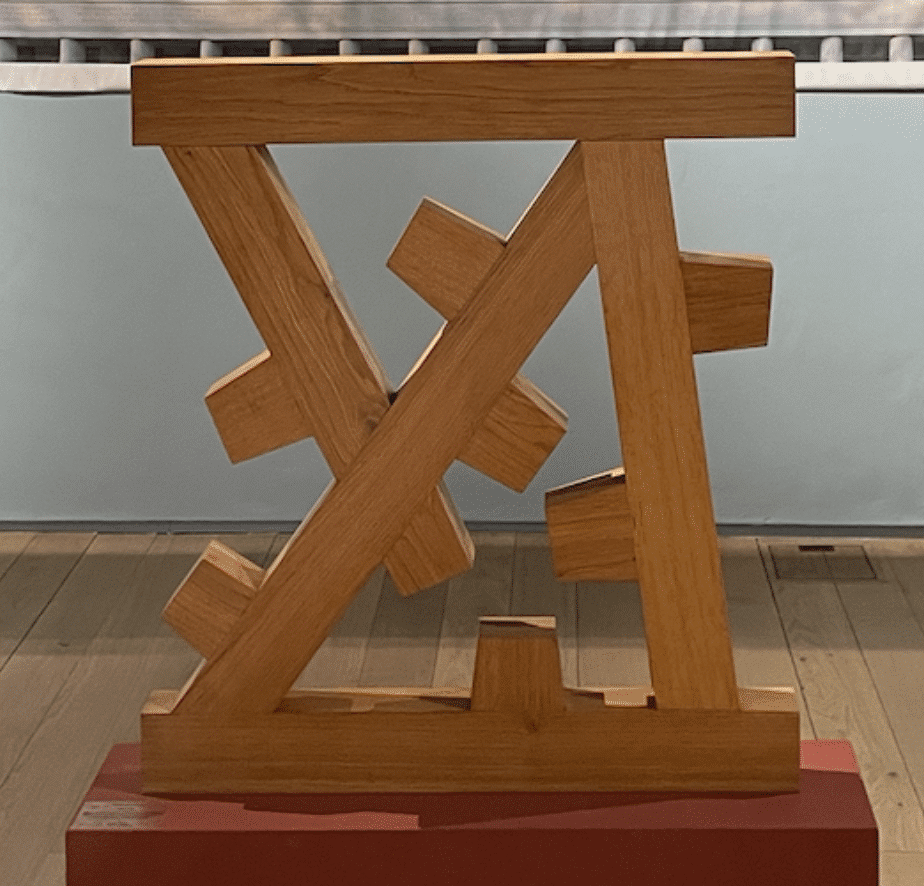

Among the more enduring strategies for reconciling things and thought, earth and world, was the Mannerist and Baroque concetto, the synthesis of image (in the perspective, via the quadrivium) and word (through rhetoric, via the trivium) that developed from the emblem and impresa, and which turned on how the disegno esterno (the realised artefact) embodied the disegno interno (the idea) of an artist who was, in turn, an embodiment of God[18]. Wittily exemplifying the possibilities of the concetto in contemporary terms, therefore only implicitly imbued with the Neoplatonic apparatus that supported the original, is the garden gate by Peter Coates that Barry installed as a link between the architecture and the concrete poetry. Coates is perhaps better known as a stone sculptor and a late collaborator with Ian Hamilton-Finlay; but this sturdy wooden gate is made of the letters Y-A-T. Consensus holds that this is Yorkshire dialect for Old Norse gata, meaning gap, way, passage, as also found in Symond’s Yat, downriver from Hay-on-Wye (indicating that the historical Taliesin hailed from northern England). The three letters are vertically symmetric and so read the same from either side unless one strays onto TAY, whose Middle English cognates include thy, they, though, two and thigh, not to mention the ‘strong, silent flowing’’of the Scottish river or the Irish for ‘tea’, often a euphemism for liquor. As a concetto, the word is the image, particularly when, as here, the gate is extracted from its fence or drystone wall and parades as an object more than a passage. To explicate the term gate requires two full pages of the Oxford English Dictionary, indicating how rich an architectural metaphor it is, poised between allowing (often with considerable ceremony) or prohibiting (with arms or injunctions) transition from one realm to another.

The ludic quality of Coates’ gate is shared by the other examples of concrete poetry that Barry exhibits, whether historical precedent, such as William Gager’s pyramid poem for Sir Philip Sydney and Apollinaire’s Calligrammes) or recent work, such as Made Up True Story, by Sam Winston, which embeds hyperlinked words in earth to suggest a cairn of possible meanings. An exception to this playful spirit is David Henningham’s silkscreen print, Grand Eagle (capitals and columns), where the agonic play becomes outright violence. The translucent skeins of primary colours overlap to leave in white the letters of barely-readable words taken from his mordant forty-two page poem, An Unknown Soldier: A Poem, in Three Parts, on the First World War. This commemorates the war’s centenary, in which the forensic details of ghastly slaughter are interwoven with phrases from letters home, condolences from senior officers to bereaved families, the terminology of official heroisation and, in the poem’s second part, fragments of argot from both sides of the trenches.

Henningham describes the image:

‘The main text is our soldier’s own paradoxical definition of humanity [from Part Two], “Able damned est/ N thing worth saving/ N harvest thrives/ On our mass graving.” We have chosen an epitaph from Preparatory Oratory [Part One], “MCMXIV fire guns at a useless trajectory MMXIV”, screenprinted in gold beneath. The enlarged capitals, as found in medieval manuscripts, spell out ANNO to remind us of the centenary year, but also to suggest capital cities found on a map of the world, surrounded by fortifications in the shape of each sentence, or perhaps columns of soldiers marching towards the vanishing point of a no-man’s land.’[19]

An isometric does not, of course, have a vanishing-point; and, by extruding block solids through the voids within and surrounding each letter, the quartered field of the isometric text manages to be at once a city, a vast cemetery, a trenched no-man’s land, an army in formation, a bandage and a battle flag shot full of holes — the exposed remains of the words. Hemmingham acknowledges Vorticism and Dazzle-Painting as graphic inspirations from the period; and, as Barry’s posted notes indicate, the craft of making the image and poem generates relevant puns: Grand Eagle is a paper size and suggests heraldry; Trench also names a typeface; column refers to typography, to aligned soldiers, to architecture; capital refers to letters, to financial resources, to a centre of government, to that which is excellent, to a crime punishable by death, to the head (from Latin caput, in turn calling up the German kaput) of a column.

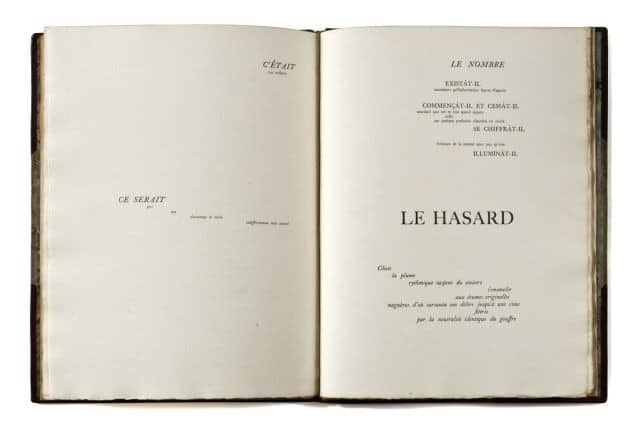

However this self-referential play with the analogic spatiality of typography, present also within the layout of An Unknown Soldier, has its source in Stephane Mallarmé’s epic poem, Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance), first published in 1897, but issued in book form only in 1914[20]. Across twenty-two pages a ship founders and breaks up in ‘the Abyss / raging / whitened’; and, at the end of the poem, the shipmaster, adrift amidst the wreckage, is granted a glimpse ‘towards / what must be / the Wain [Big Dipper] also North / A CONSTELLATION’, as if orientation, even navigation, might still be possible. Again, traversing the span between the earthly abyss and heaven, the poem appeared a year before Mallarmé died. Two years previously, he had published Sonnet III, Dans le doute du Jeu suprême (In Doubt of the Supreme Game), in which he contemplated the end of poesy in its traditional form — what he called, in his 1897 Preface to Un coup de dés, ‘the older verse, for which I maintain my worship’. Adducing developments in contemporary music, that preface devotes most attention to the great areas of vacant whiteness across which the words of Un coup de dés are distributed, in four type fonts (‘the dominant motif, a secondary one and those adjacent’): ‘[t]he “blanks”…the surrounding silence…[t]he paper intervenes each time as an image… this print-less distance which mentally separates groups of words or words themselves….’ The shipwreck of poetry casts its words like jetsam swirling in the gulf (of the white page), from within whose turmoil the ship-master poet catches sight of a constellation in the sky (of the white page), a superimposition which obtains in the white page of thought (‘the print-less distance which mentally separates’). A decade before the advent of Cubism (but contemporary with August Schmarsow), Mallarmé here identifies the characteristics of space as a drama of poesie, the creative power underlying the Romantic project to build a secular culture through Art: the page on which culture is written is a gulf in which the poet-vates might drown, along with the wreckage of tradition, and this page is also the sky offering uncertain hope in the new conditions. The void of space, legacy of the sublime, places all fragments at the disposal of poesie. It flattens every alternative, from quantum physics to individual psychology, to an equal value — a gulf and sky of potentially interesting allusions — provoking Mallarmé to conclude that the Supreme Game had become a game of chance: ‘All Thought expresses a Throw of the Dice’.

The consequence of losing compelling poetic analogy becomes evident when placing Un coup de dés alongside the words equally vexed by space in Henningham’s Grand Eagle image. The ancient Indo-European tradition, still very much alive in the Taliesin cycle, whereby the frenzy of poetic inspiration and that of battle were closely related to each other and to a religion oriented to dying-reviving nature eventually becomes, via the more detached or intellectual Romantic poet, the sardonic wit by which Henningham discovers meaningless slaughter and empty words in World War I[21]. Conversely, it could be argued that Henningham’s position is more honest to the case and more likely to promote abhorrence of war, as the collapse of the symbolic hierarchy is perhaps a natural transition to a universe understood in terms of information entropy. On these terms, some will regard it as nostalgic, others as recovery of orientation, to read Heaney’s angelic navis as an attempt to preempt Mallarmé’s shipwreck, to see the aleatoric aspects of Cox’s cento as challenging Mallarmé’s concern with chance by organising itself as a quartered horizon, and to believe that the works of McLaughlin and Parry have striven to rescue contemporary architecture from space, with its persistent appeal to formal coherence rather than to profound interpretation of its topics[22]. The literary involvement with violence, from Nietzsche through Bataille and the formalism of the Nouveau Roman and Barthes, with their flat language eschewing notions of depth, would seem to have evolved into the ever-deferring verbal ecology of Derrida as the forest in which occurs the Heideggerian clearing. However, this order, like that of the natural world or of any living metabolism, including cities, is so vastly complex at so many different scales, levels of embodiment and varieties of temporal intervals and cycles that its proper understanding calls for new paradigms, styles of thought, representation, and communication. For the most part, we situate ourselves in this milieu by taking it for granted; and the greatest benefit of the current state of so-called artificial intelligence is to have alerted us to how deep are the ordering processes on which we depend. These ordering processes are only partly logical, probabilistic, or systematic, since they also seem to require ambiguity, error, conflict, violence, decay, death and renewal. If some equivalent to the old symbolic hierarchy is to arise from a concrete understanding of this order, it will, like the ancient cosmologies, come from trying to comprehend it ethically.

Fabio Barry ‘Poetry and Architecture, Where Words Take Shape and Poems Become Buildings’ is on show at Hay Castle, Hay-on-Wye from 26th May 26 to 3rd September 2023.

Peter Carl is a teacher of architectural design, history and philosophy, emeritus of the University of Cambridge and London Metropolitan University.

Notes

- G. W. F. Hegel. Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics, trans., Bernard Bosanquet, Penguin Classics, 1993, pp. 88, 97.

- Dalibor Vesely, ‘The Architectonics of Embodiment’, in Alex Stara and Peter Carl, eds., Dalibor Vesely, The Latent World of Architecture, Routledge, 2023, p. 82.

- Martin Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, in Poetry Language, Thought, trans., Alfred Hofstadter, Harper Colophon Books, 1971, pp. 15-87.

- Plato, Phaedo 67d ff., developed into what we would call an ontology in Republic 471c-541b; the beautiful, luminous and true: Philebus 51a ff.

- John 1:14 in the Vulgate, et Verbum caro factum est, ‘and the Word became flesh’.

- Defence of the Divine Images I.32.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans., Colin Smith, Routledge, 2002 (from 1962); Dalibor Vesely, Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation, MIT Press, 2004, Chapter 2; Albert Newen, Leon De Bruin, Shaun Gallagher, The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition, Oxford University Press, 2018.

- George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, University of Chicago Press, 1980, and Philosophy in the Flesh, Basic Books, 1999.

- Rensselaer W. Lee, ‘ut pictura poesis, The Humanistic Theory of Painting’, now a book, originally in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 22, No. 4, Dec., 1940, pp. 197-269.

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ‘On Poesy or Art’ [originally notes for a lecture in 1818], in Walter Sutton and Richard Foster, Modern Criticism Theory and Practice, New York, Irvington Publishers, 1988, p. 39: ‘Believe me, you must master the essence, the natura naturans, which presupposes a bond between nature in the higher sense and the human soul’ (a theme which eventually attracted Nietzsche’s concept of the will to power as art).

- See: https://www.haycastletrust.org/ (accessed 4.7.23).

- Jean Petit, ed., Le livre de Ronchamp Le Corbusier, Les Cahiers Forces Vives, 1961, p. 18.

- Lecture delivered in 1951, now in Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought, op. cit., pp. 211-229.

- That is, the navis, or nave, recalling Noah’s Ark and the boat of St. Peter.

- Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, Beacon Press, 1969 [orig. 1958], Introduction and pp. 17 ff.

- This can be compared to the Gundestrup Cauldron, which contained awen (inspiration).

- The source for early Welsh poetry is the early fourteenth century Book of Taliesin, translated by Gwyneth Lewis with Rowan Williams.

- Disegno = segno di Dio in noi, according to Federico Zuccari, L’Idea de’ pittori, scultori ed architetti, 1607.

- https://henninghamfamilypress.co.uk/grand-eagle/ The Hemingham Family Press paperback edition of the poem, 2014, has rendered the passage from Part Two as: ‘What est n human but / that which est able to est / damned? / What est n man but n thing / worth saving?’.

- All translations are those of A. S. Kline, originally 2007, now collected in Stephane Mallarmé, Un coup de dés and Other Poems, independent publication with illustrations by Odilon Redon, 2018, pp. 75 ff.

- M.L West, Indo-European Poetry and Myth, Oxford University Press, 2007; David W. Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel and Language, Princeton University Press, 2007; Gwenyth Lewis and Rowan Williams, trans., The Book of Taliesin, Introduction, Penguin Classics, 2019.

- This last is the basis of Vesely’s poetics of architecture inspired by Aristotle’s mimesis of praxis, in Divided Representation, op. cit., Chapter 8.