Le Corbusier and the Poetry of Objects

The consideration of objects shapes the mind, providing it with resources: sliced butcher’s bones, shells that are whole or broken by the tides. . . . Nature also teaches sharpness, the rigour of functions.

— Le Corbusier, Unité [1]

Around 1928, Le Corbusier abandoned the universe of manufactured objects, having exhausted all the devices and formal resources he could discern in that realm. In this way, he escaped the demanding intellectual limits imposed by Purist doctrine. Returning to the original milieu of childhood – nature – he discovered freedom of expression ‘at the tip of a pencil’, a practice he would continue to embrace for the three decades that followed. He was now preoccupied with ‘witnesses of organic life’, collected during his travels and walks:

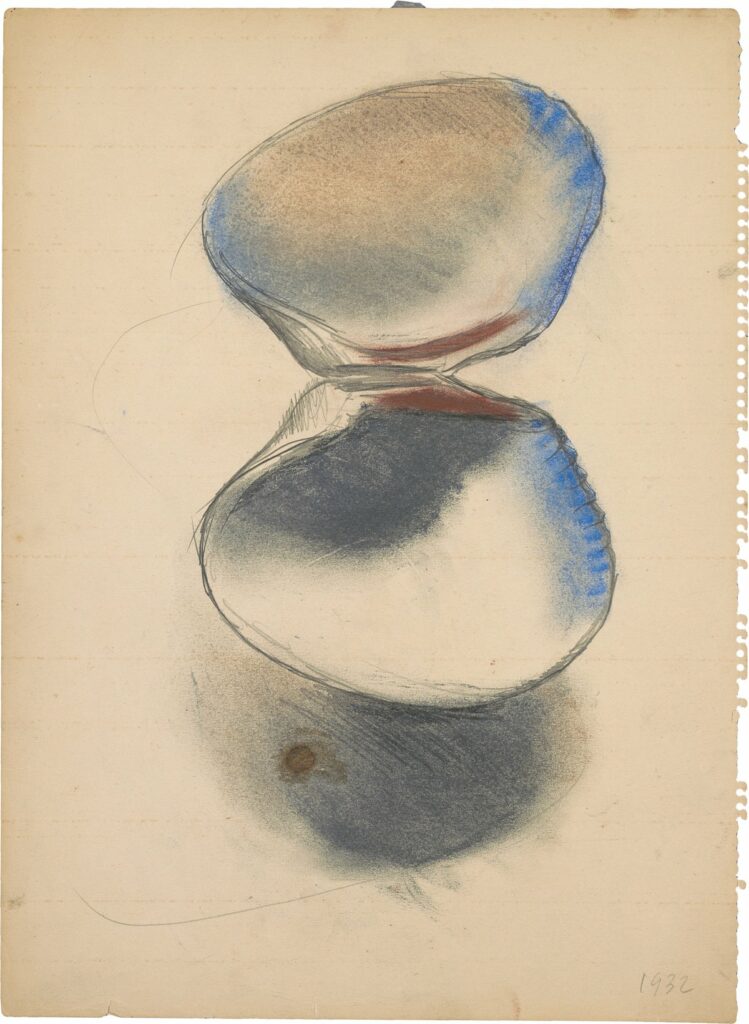

‘Witnesses qualified as objects which evoke a poetic reaction are those which by their shape, size, substance and durability are worthy of a place in our homes. A pebble polished by the ocean is one example, another might be a broken brick rounded smooth by lake or river waters, or bones, fossils, tree roots or algae, sometimes almost petrified, or whole shells smooth as porcelain or carved in Greek or Hindu fashion. Broken shells reveal their amazing spiral structure to us. All these seeds, flints, crystals, pieces of stone and wood form the vast panoply of spokesmen who speak the language of nature. They are caressed by your hands, your eyes gaze upon them, they are evocative companions…; By means of them friendly contact between nature and ourselves is woven.’ [2]

During one of his summer sojourns at the Bay of Arcachon, he completed an album of pastel studies of seashells, pebbles, roots, and bark found on the beach at Le Piquey. [3] ‘Natural fragments manifesting physical laws, wear, erosion, rupture, etc., possess not only plastic qualities but also an extraordinary poetic potential.’ [4]

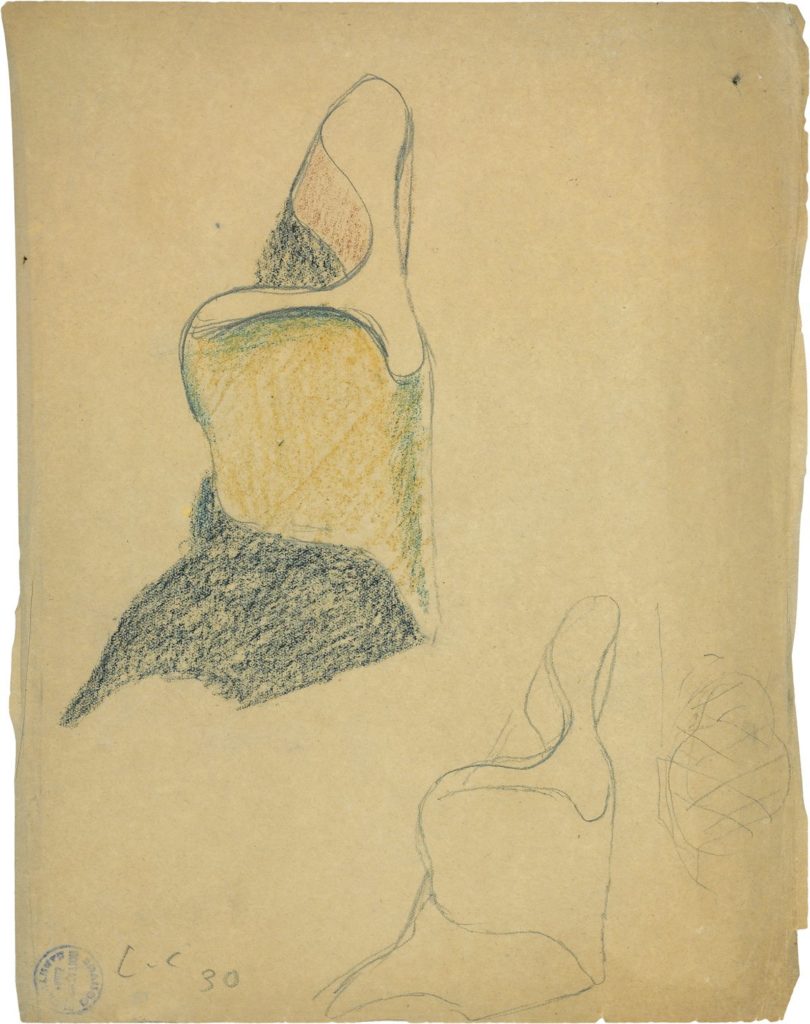

While objects from the earlier thematic repertoire still appeared at the beginning of this creative phase, they were transformed into strange shapes, and the drawings became the vector of the imaginary. The approach Le Corbusier had employed since his early years in La Chaux-de-Fonds overtook the mere depiction of the real and the simple visual description of things. Drawing, which from the beginning had been a ‘way of seeing’, now became the tool revealing ‘the secrets of form.’ If at the beginning of his graphic work drawing was the way to transcribe the structure and the hidden order of natural forms, it was now the engine that drove the artist to explore an inexhaustible plastic universe.

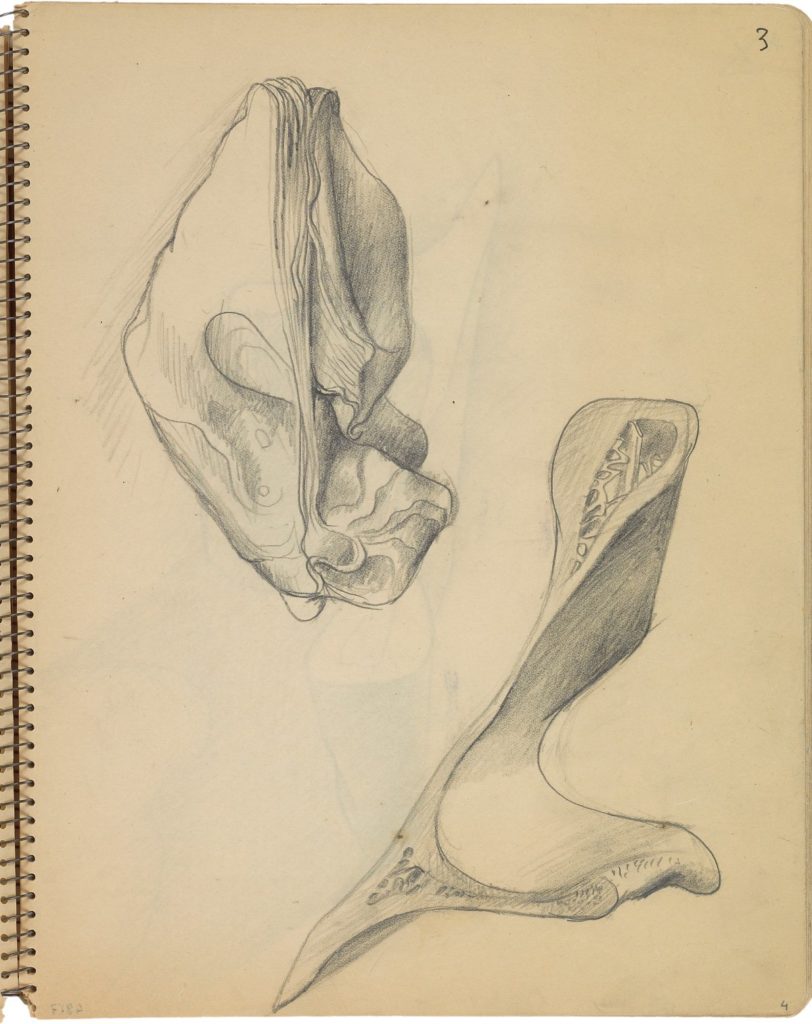

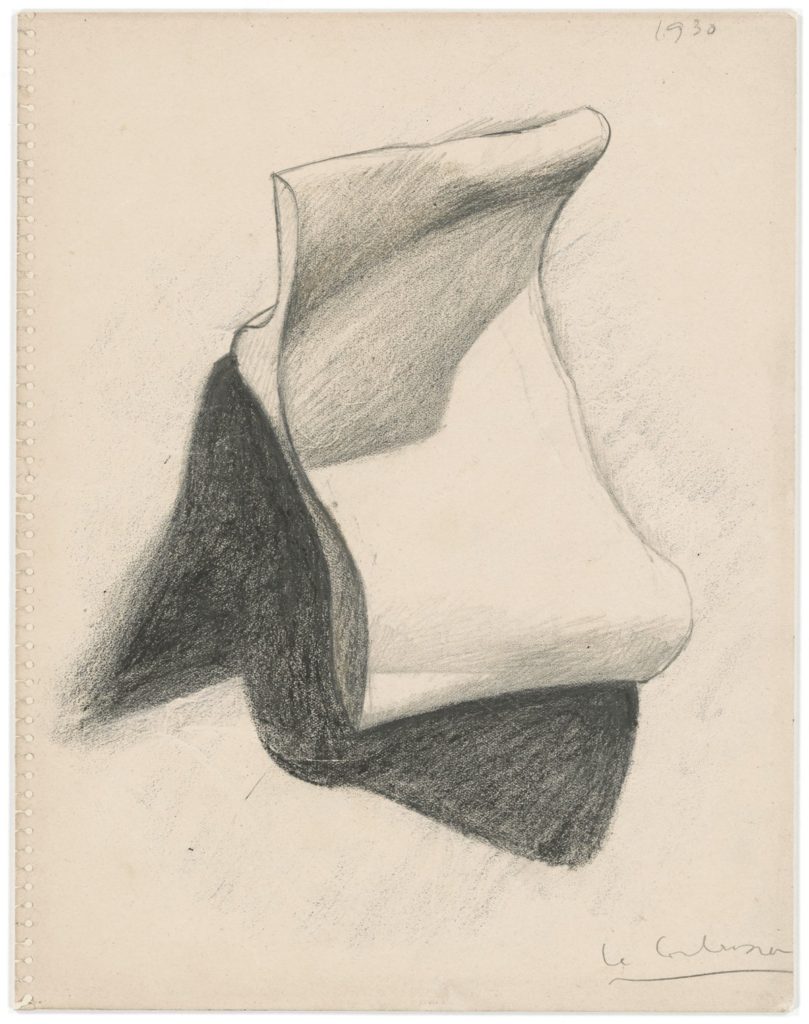

In his 1960 publication L’Atelier de la recherche patiente, Le Corbusier published three drawings representing a shell and a bone whose shape is split by a wide shadow. These drawings represent the continuation of studies made three decades earlier in a spiral album, the support he began to use in the early 1930s. [5] He described them thus:

‘These objects are prevalent everywhere under your feet. If you have a pencil in your hand, you will look at them and you will understand many things; you will now have a stock of meaningful values which are the lesson of natural phenomena. And even arbitrary intervention: the shattered shell or the blow of butcher’s saw in a scapula brings riches that the mind alone cannot detect.’ [6]

In one of these studies, he carefully analysed a butcher’s bone from its various angles. [7] This element seems to be the ‘object of poetic reaction’ that most fascinated the draughtsman. He delightedly drew in pencil the serpentine lines, the sinuous and feminine shape, the dancing silhouette. His favourite version shows the bone balanced on the thin and rounded part of one of its sides, lending it an almost human form. The bone inspired a dozen themes in his paintings. [8] From 1929 to 1931, it was linked with a box of matches, a glass, gloves, and a female body in Sculpture and Nude; with a violin in Composition with Violin, Bone, and Saint-Sulpice; with human forms in Black Woman, Red Man, and Bone; with a stylised head in Mask with a Pine Branch; with an oyster in Léa; and, finally, with other organic elements in Still Life with Root and Yellow Rope. [9]

Extracted, with permission, from Le Corbusier: Drawing as Process by Danièle Pauly, translated by Genevieve Hendricks, and published by Yale University Press © 2018. The publication is available at YaleBooks.

Notes

- Le Corbusier, Unité, p. 44

- Le Corbusier, Entretiens avec les étudiants des écoles d’architecture (Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1957), n.p. translated into English as Le Corbusier Talks with Students from the Schools of Architecture, trans. Pierre Chase (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1961).

- See album FLC CA2, notably FLC 4817 to 4832, and album FLC CA13, from which Le Corbusier tore pages [FLC 1967 and FLC 1968] to include in two large travelling exhibitions in the 1950s. See also the notebooks from Le Piquey.

- Georges Charbonnier, ‘Entretien avec Le Corbusier’, Le Monologue du peintre, vol. 2 (Paris: Julliard, 1960), p. 107.

- See the album from 1932, FLC CA13, and drawing FLC 5953.

- Le Corbusier, Creation Is a Patient Search, p. 209

- The butcher’s bone was drawn from all angles in album CA2. The first drawing of the mask appears on page 12, dated 1930.

- See also the hypothesis set forth by Claude Prelorenzo in ‘Gammes cinématographiques’, Le Corbusier: Aventures photographiques (Paris: Éditions de la Villette, 2014), p. 71. The author published two sequences of Le Corbusier’s cinematographic attempt to represent the elements and captioned ‘Three sawed butcher’s bones—a study model for Ronchamp?’ (p. 83).

- See Bruno Reichlin, ‘C’était Léa . . . ,’ in Le Corbusier, le jeu du dessin, p. 68.

– Robin Evans