Roger Katan and Forum

I consider it a good rule for letter-writing to leave unmentioned what the recipient already knows, and instead tell him something new—Sigmund Freud

The first time Louis Kahn ate couscous was some time around 1962 or 1963, at Roger Katan’s house. Katan was relatively new to Kahn’s office but as the only French-speaker he had found himself close to his employer, editing an entire issue of l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui devoted to Kahn. He was soon put in charge of other projects, just one of five employees when he started, but before too long part of an expanding team of thirty-five, assisting on a collaborative project in Islamabad with Doshi and working twenty-four hours straight on designs for the Salk Institute alongside Anne Tyng, Kahn’s mistress, whose work Kahn credited as his own, except for the child that they produced together.

During this period Katan, who rarely had time to see his own wife and kids, often hosted his boss at his house. Hence the couscous – a taste of Katan’s childhood in Morocco (memories of a place so dry that scratching the mud walls of his grandfather’s home made them flake apart) but served on a platter on a dining table with a tablecloth in Philadelphia. Once the children had been put to bed, conversations around the Maghrebi dish would extend long into the night.

I had been trying to track down Katan for weeks. Finally we made contact. It is the middle of the afternoon, and the man himself is talking to me on the phone, reminiscing, while – as he admits – sipping Japanese whiskey somewhere in southern France. ‘Kahn was a special animal, fantastic, but he was so self-centred I couldn’t stand to stay long’.

Up until this point Katan had rarely stayed anywhere for long. He was born in the same mud house as his father and ‘did all my primary strides in that small village’ in Morocco. He attended architecture school in Algiers and then moved on to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. After an enforced three-year period of military service in Paris he moved again, this time to the US and MIT, where he began a fellowship in the masters programme aged thirty. ‘But I was bored. The rest of the kids were twenty-two with no life experience’. Katan had a wife and a kid and was itching to see America and its architects. He’d often walk across Cambridge to Harvard, where the masters students were closer to his age (‘that’s where I first met Doshi’). One day Louis Kahn gave a lecture, and ‘I knew I had met my real father in architecture’, he recalls. Afterwards Katan asked if there were any openings at the office. Kahn hired him on the basis of his fluent French (and Roger was the highest paid member of his staff because of it).

I stayed two years and they were two full years. When I say two full years I mean days where I had time to sleep four hours and would then spend the rest of those twenty hours with Lou. The problem was that he was everywhere even when he wasn’t in the office. It was a sad moment when I decided to leave. I didn’t know where to go, or how.

Instinctively Katan moved in the opposite direction, away from the well-paid, cloistered office job, away from the high-profile projects and celebrated boss, away from his bourgeois Philadelphia life altogether. Instead, in 1965 he moved his family to East Harlem, into a house that was slated for demolition. His father-in-law had set him up to manage the construction of a nursing home, but the project was short-lived. ‘I said for the same money I could build better. They said you have to build our way or you won’t build anything. I told them, Fuck you, and left’.

But East Harlem was already leaving its mark on Katan, and he stayed in the neighbourhood. Since the 1950s the area had been made up of mainly Italian, Black and Puerto Rican families, but the buildings, houses and municipal services had long been neglected by local authorities. Robert Moses had ignominiously authorised the neighbourhood’s swimming pools to be filled with freezing water to discourage Black families from attending, and he was eager to raze entire blocks in favour of highways, erasing the community altogether. There were fights with the police. ‘One day they charged us, they ran us down 3rd Avenue and 124th Streets’, Katan tells me. ‘I lost my shoes and was running in bare feet. There was heat everywhere. All of us who lived there were fed up with the police and official things’.

Community groups were organising. Katan bought a cheap building on 116th Street. He rented the fourth storey to a Puerto Rican family, kept the third storey for himself, and turned the first and second floors into his practice. At any given time, six to fifteen people worked there, and everyone was paid, even if only very little.

The problem of East Harlem was mainly with the local authorities who didn’t want to hear about improving in the manner the community wanted to, but improving instead in the manner they wanted to improve. They wanted to improve with horrible projects that looked like jails. I was so angry with the housing authority, and they were fed up with me, of course.

East Harlem was the turning point in my life because of the participatory experience. It’s another world altogether. In one you impose things. The other you compose things, with the people there. How could you impose things on someone who has nothing to do with those kinds of conditions? I couldn’t impose tacky-tack houses. I refused.

Katan’s idea wasn’t necessarily to serve as the neighbourhood’s architect but to provide groups with the architectural and technical assistance and expertise to submit their own proposals. Out of his teaching at Pratt with Sibyl Moholy-Nagy he created one of the earliest community design centres. ‘I remember working on this project at a time when I wanted architecture to change and be more welcoming to people’, he says. ‘I wanted a facade that would tell people, “Come in. We are here to help you live better”’.

This was the beginning of a decade-long series of projects between Katan and the communities of East Harlem, a timespan in which the community design centre, housing and social projects would be realised.

It is also a period of architectural activism that I knew nothing about, at least until a slim box arrived one day with the message, ‘Can you do something with this?’

* * *

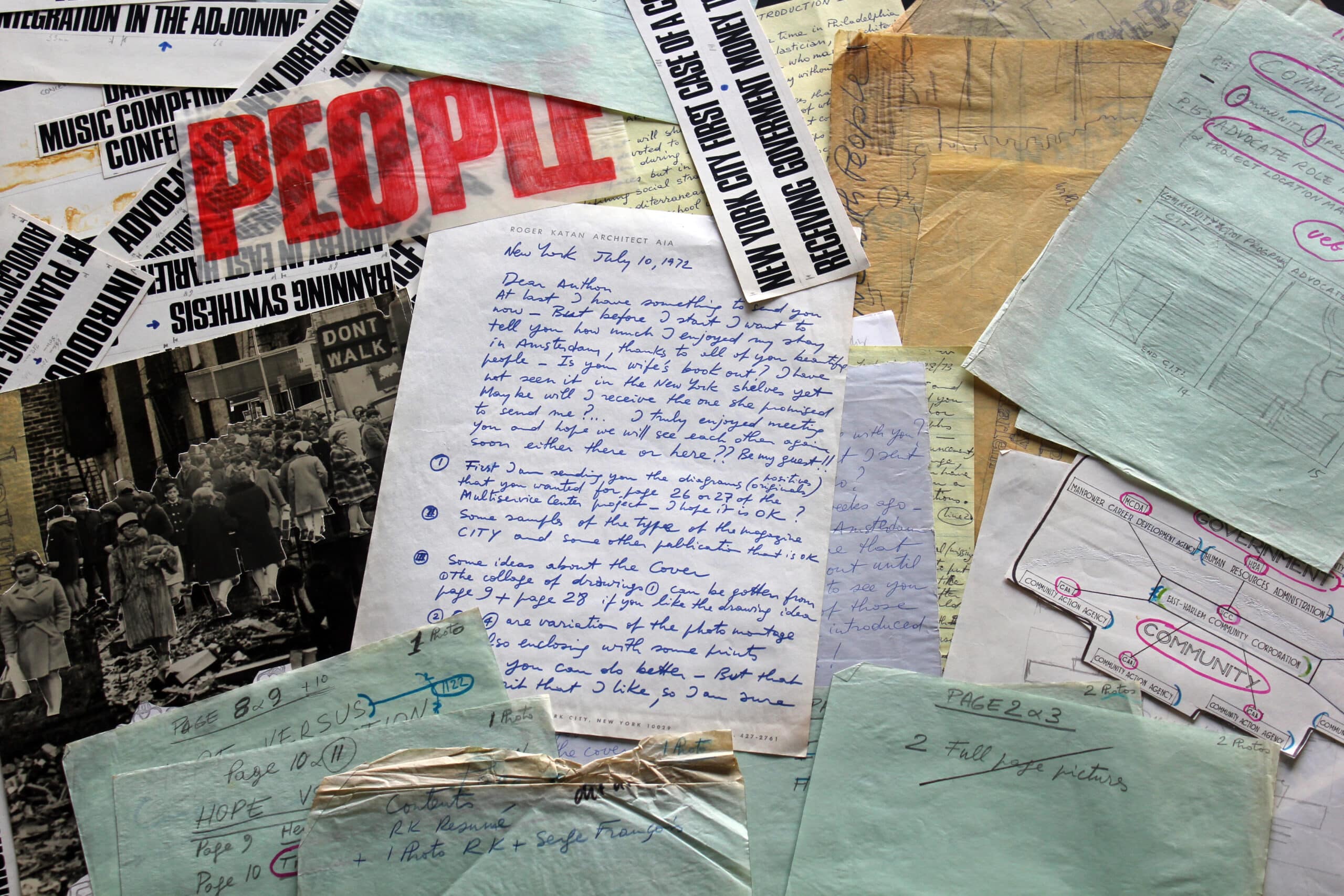

My first pass through the pages is a kind of epistolary sifting of mailed and typographic letterforms. It is an archaeology, a deciphering of characterful hieroglyphics to determine what it all means. Letters sent from the office of Roger Katan in East Harlem to the office of Anthon Beeke in Amsterdam. Ruled sheets of line corrections. Sketches of page plans. Cut-outs of heavy lettering. A collage paste-up of what must be the cover of a magazine, with ‘FORUM’ jotted out in pencil, almost lost in the bottom right corner. The clues are there if you know how to read them.

July 10, 1972

Dear Anthon,

At last I have something to send you, but before I start I want to tell you how much I enjoyed my stay in Amsterdam, thanks to all of you beautiful people […] first I am sending you the diagram you wanted […] some samples of the type of the magazine CITY […] some ideas about the cover […] I know that you can do better but that is the spirit that I like […] Now it is your turn to work…

Roger

Here was the opening gambit for an issue of a magazine all sketched out, but there is no reply from Anthon Beeke. His absence from these artefacts makes sense given that the material comes from Beeke’s own archive, the recipient who kept everything (a brief list of the contents of the slim box confirms this). It turns out Beeke died in 2018 and was the enfant terrible of Dutch graphic design, celebrated for his posters and famous for his letterforms made from photographs of naked women: (‘I admit: it’s absolutely unreadable and hence unusable. But if you’re going to make something unusable, you can at least make something people are able to enjoy’). Evidently it was a small jump from the Naked Ladies Alphabet, later renamed Body type (appropriately, or inappropriately, released in 1969) to editing an architecture magazine called Forum in 1971; a small jump from the previous editors, Aldo van Eyck and Jaap Bakema and their takedowns of CIAM, to Beeke the enfant terrible.

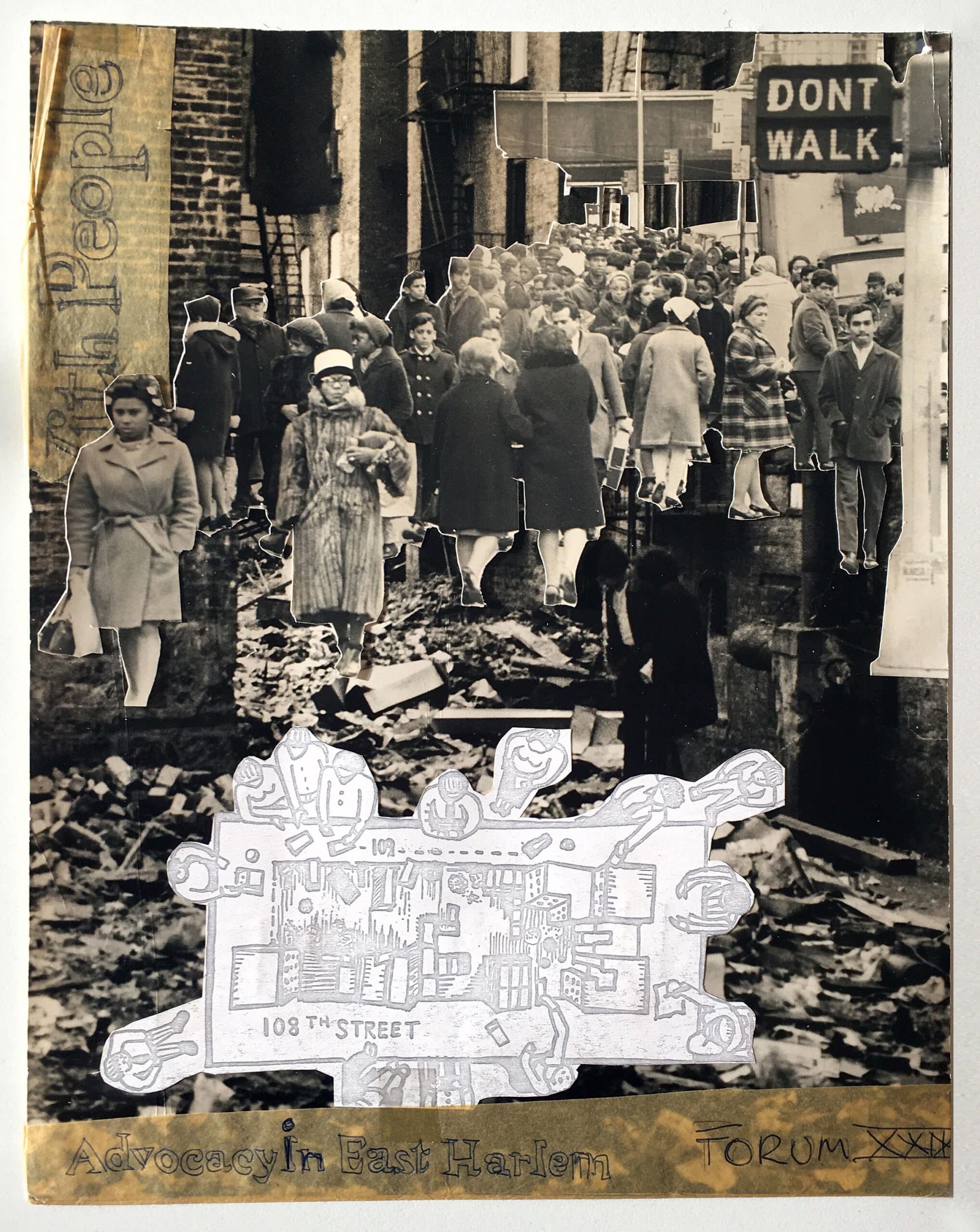

In the absence of any of Beeke’s responses or replies, the slim box instead offers only the one-sided editorial project of Roger Katan, whose ambitions and anxieties creep up fast off the pages. Thumbing the hand-cut layers of the collaged cover – its pictures of people, the hand-drawn table, the taped border with the pencil lettering – his sincerity and dedication to whatever the final outcome might be is unsettling, uncomfortable. So much is going on in the masses of people, glued over one another, that nothing is clear. He doesn’t even have room to run his entire issue title, ‘Planning with People’ – the typographic treatments of this and his wordy misspelled subheadings are enclosed on other sheets.

‘Can you do something with this?’

Yet it’s impossible not to admire Katan’s confidence. Here is all the content. This collaged cover is the right cover. And it’s difficult not to immediately relate to his simultaneous annoyance and fear at not hearing back from his collaborator:

November 6, 1972

Dear Anthon,

What the hell is happening with you? Have you even received what I sent you two or three or four months ago?

At some point it seems Beeke wrote back, and even sent Katan something close to a final draft of the magazine, because enclosed with Roger’s next reply are pages of corrections.

Page 13 1st column, Line 1: Change title to CHURCHES VERSUS PEOPLE

Page 16 3rd column, Line 9: KINGDOM is spelled with a G

Page 22 You forgot the legend of the two maps

Page 23 Too many black lines between paragraphs are meaningless

Page 26 Line 12 PLAGUED with a G

It goes on and on, tiny blue letters squeezed from a ball-point pen across six pages of lined yellow legal paper. The corrections are ferocious in their sheer mass. Underlined and in all-caps they bark from the sheets, and then…

OUF!! That is it for the corrections. It is your turn now dear Anthon.

Just before he signs off, Katan plants a clue:

The cover seems to be dry and stark. I would have liked to see a background of photos of people…you are the BOSS. But I like the lettering.

So unsurprisingly, it seems, Beeke didn’t care for Katan’s cover.

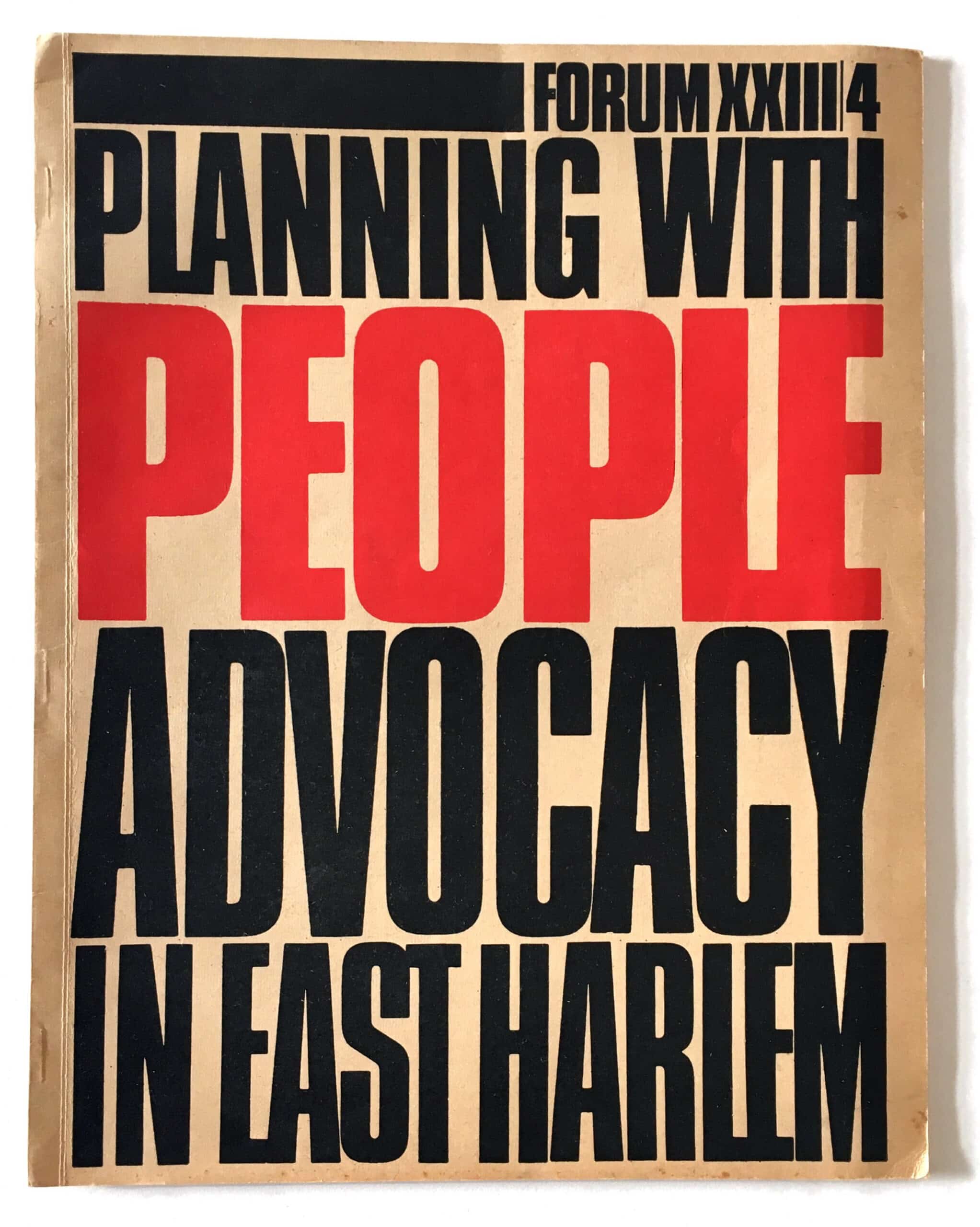

I become obsessed with finding the issue. There are few breadcrumbs on the internet, and image searches yield no promising thumbnails to preview how it might have eventually looked. I can’t even be certain of the issue number listed on Katan’s draft cover because the magazine took so long to produce that others could have been released in the interim. I comb through the online catalogues of Dutch bookshops and finally find an empty grey box where the thumbnail of the cover should have been, accompanied by ‘Forum XXIII – 4 Planning with people advocacy in east Harlem’. I pay €20 plus shipping to Bestelling Boekwinkeltjes.nl. The magazine arrives a month later.

This is in fact Anthon’s reply. A wholly typographic treatment. A literal characterising of Katan’s people on the page. It is not ‘dry and stark’, as Katan suggests, but urgent, clarifying, characterful.

Inside, the pages of the magazine are jammed, almost spilling out of their tight Dutch grids with the community projects of East Harlem. These layouts are virtually identical to what Katan had sketched out and sent to Anthon back in July. But the cover, in its opposition to Katan’s collage, seems to explain the unanswered mail. A give and take. A bargaining. Forty-one pages as you like them, Roger, in exchange for one good cover. It’s all a funny kind of play on words, given than Katan was working in a neighbourhood that was founded by a Dutchman and called Nieuw Haarlem.

This is usually where the story ends. The book gets made. The magazine issue gets printed. We try not to look too closely at the finished object before us for fear of the mistakes, the howlers we let slip through. It goes onto the shelf, and we go onto the next thing. But I keep returning to those fragments in the slim box, abstracted from an archive, devoid of explanation. I have a middle, but no beginning or end.

Roger Katan has a Wikipedia entry, but no email address is listed online. I learn that he wrote a book with the planner Ron Shiffman who is listed as a visiting professor at Pratt. I write to Shiffman who passes my message onto Roger. Another kind of epistolary story transpires.

Dear Professor Shiffman,

Recently I came across a box of material related to Roger Katan’s issue of Forum magazine, produced with the Dutch designer Anthon Beeke, between 1972–73. There are pages of correspondence from Roger, as well as layouts by him, which he sent to Beeke in Amsterdam. I’m writing to ask whether you have any contact details for Roger, knowing that you wrote Building Together with him, and if you would be willing to share these with me.

While I have been able to piece together a lot about the editorial process from Roger’s own correspondence, I would be thrilled to speak to him about his experience making the issue.

Best wishes,

Sarah

One week later I am on the phone with Roger Katan, now ninety-one. He sounds relaxed and sunny on the other end of the line, eager to go back in time for my benefit. He tells me about Lou Kahn and the couscous. About his own father, and his architectural father. About working in Islamabad and about Doshi. About Kahn as an increasingly elusive figure, the boss who would spend time with every person in his office until he was never there. We talk about his work with the UN building mud houses for villagers in Benin and how it reminded him of the mud walls of the house his grandfather built, the one Roger was born in.

The actual issue of Forum is peripheral to all this, simply the happy and deserved result of ten or fifteen years of going to work every day in East Harlem, a period and place whose details still perfectly coalesce in his memory. Fights with the housing authorities, teaching a neighbourhood guy named Henry how to draw (his drawings are in the issue), designing an apartment for the elderly – ‘the building had to be high-rise, and I imagined a tower where each floor would have four apartments, each one communicating with the other through balconies, so the residents would all come and play cards and chat. A building where each floor was a group of friends’.

Finally he tells me that when the issue of the magazine came out, everyone in the community wanted a copy.

But we’ve been speaking for over an hour and Roger is tired. It’s time to hang up, and I still don’t know how this story begins.

The next day, I have my own letter – an email – from Roger.

Dear Sarah,

It is amazing how much our conversation stirred souvenirs of old time, interesting and exciting moments in my life with friendships that have lasted up to these days. Forum started with a call I received from a group of architects who had arrived at Kennedy airport who wanted to visit my office and talk about participation in community projects.

Two weeks later, after their US tour, they told me that of all the work they had seen throughout the country they were most interested in East Harlem. They gave me carte blanche to do a whole issue of the magazine. I went to Holland to put it together.

That’s how it all started.

Best,

Roger

Sarah Handelman is an art and architecture editor.

Click here to read other texts by this writer.