The Garden Transcripts

For the past two years, our Writing Prize has attracted a large number of thoughtful texts from participants all over the world. This year we partnered with the Architecture Foundation to sponsor one of their three writing prize categories. The Drawing Matter category, titled ‘Architecture and Representation’, invited entrants to submit a short piece of writing on a drawing or series of drawings that they had studied or made.

Like storytelling, speculative architectural drawing engages with fictive worlds beyond our own. It is through drawing that architects fantasise, suspending the material and temporal limitations to look towards other worlds of untruths, strange logic and alternative realities. It is through drawing that they translate such acts of fantasy: rationalising their architectural imaginings according to terms set out by a scale rule, topographic map or the dimensions of a brick. This act of architectural speculation, which Marco Frascari calls cosmopoiesis, [1] calls upon the multiple layered existences of its subject: the tangible and intangible, social, cultural, political, temporal, phenomenological, anthropological, etc. – reaching towards ever-more-remote fields of reference until entangled in a complex network of relations. To unravel this network of relations is to partake in an act of translation.

Kate Briggs describes the role of the translator as the ‘writer of new sentences on the close basis of others’. [2] While Briggs’s essay refers to translation from one written language to another, it seems not too far from the network of cosmopoietic relations from which architectural drawing emerges. Translation is relational: the translator’s equipment for world-making reaches far beyond what can be gleaned solely from even a very good pocket dictionary. It emerges from the lived experience of a place, from fiction, conversation and repetition — those hours spent conjugating a verb or drawing at various scales until doing so becomes an unconscious act. To translate is to suggest a few possible ‘truths’ of the subject matter and try each of them on for size. Some make sense of others before casting doubt on the very things one once took to be certain.

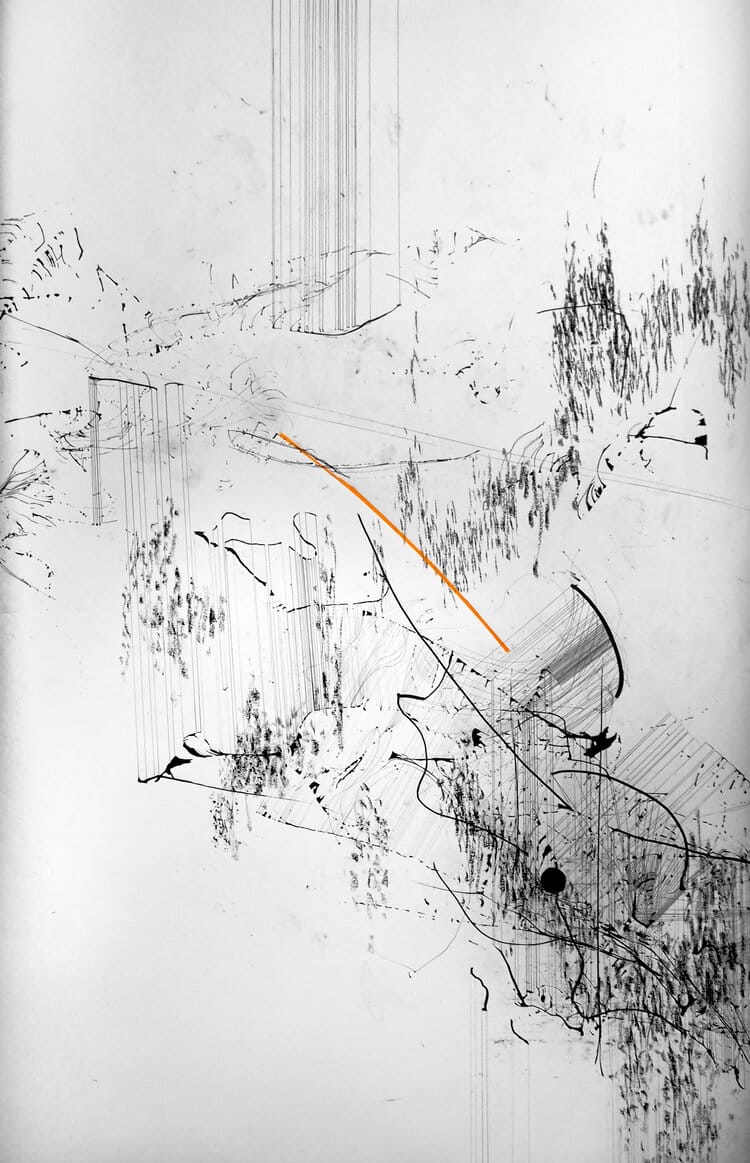

It is these relational fringes that architect and experimental cartographer Kirsty Badenoch teases through The Garden Transcripts. Where spatial design might typically be passed on through a drawing that visually and dimensionally represents the space being drawn, the ‘plan’ of the traditional Japanese garden would have been passed on verbally, or through written notation more akin to a score of music. Drawing from a translation of one such text, Badenoch invents a system of gestural notation that references conventions of architecture, choreography and cartography to draw the garden. It calls upon a range of human and non-human participants, using proprietary drawing equipment as well as invented tools particular to the work. Pilfered brushes of sorrel and oat grass impart their voice directly like phrases passing untouched from one language to another. And of course, there must be those half-truths and misappropriations that pepper any product of oral history: haphazard translations or the shortcuts of a lazy gardener. These make it into the garden, too. The drawing becomes a glimmering imbroglio of memory and metaphor. A new garden starts to emerge: a translated garden, drawn on the close basis of others. She tends to it barefoot, the paper crumples where she treads.

Eleanor Evason is a London-based MArch graduate whose research explores the narrative potential of drawing tools and tool agencies.

This text was selected as one of the runners-up in the Drawing Matter category, ‘Architecture and Representation’, of the Architecture Foundation Writing Prize 2022.

Notes

- Marco Frascari, Eleven Exercises in the Art of Architectural Drawing: Slow Food for the Architect’s Imagination (Oxon: Routledge, 2011), p.21.

- Kate Briggs, This Little Art (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2017; repr., 2020), p.45.