Sweet Disorder and the Carefully Careless: Ideas, Faces and Places (2022) – review

– Eric Parry and Robin Webster

Reviews by Robin Webster and Eric Parry, and notes from Celia Scott.

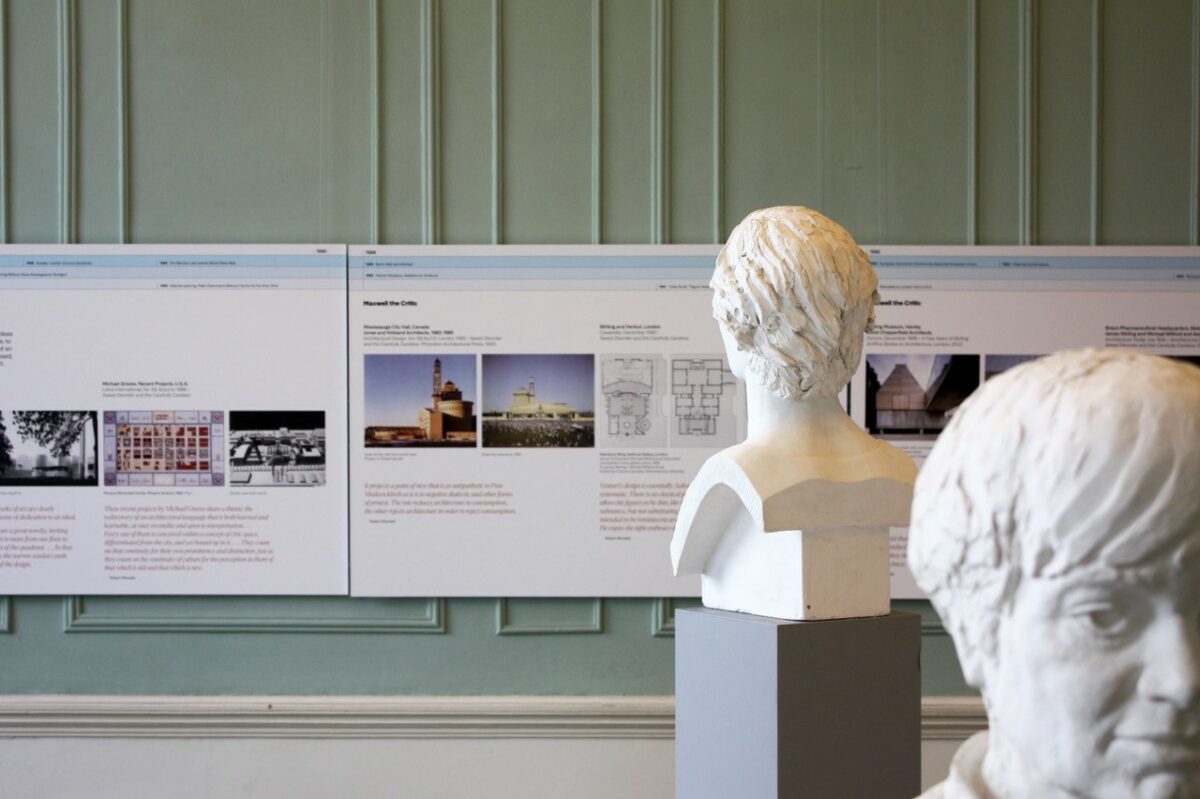

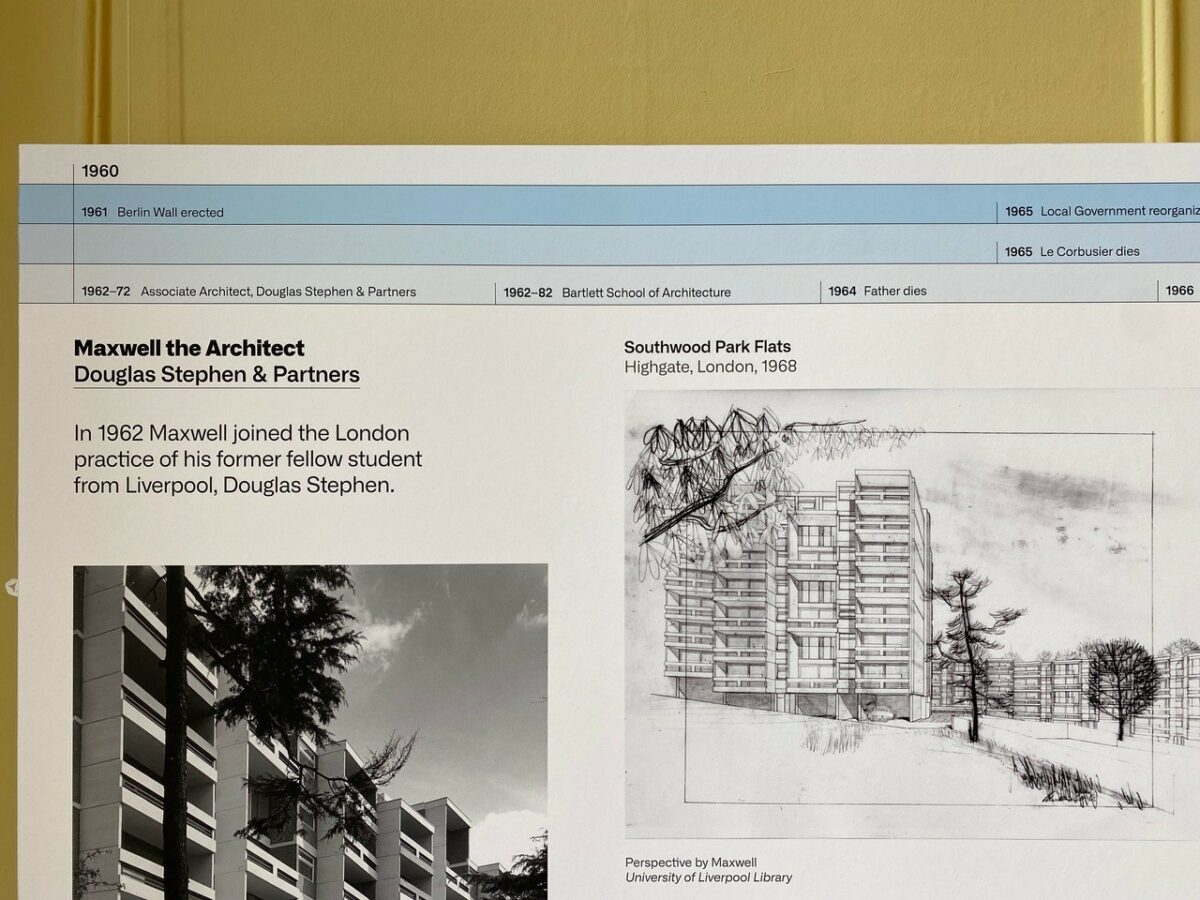

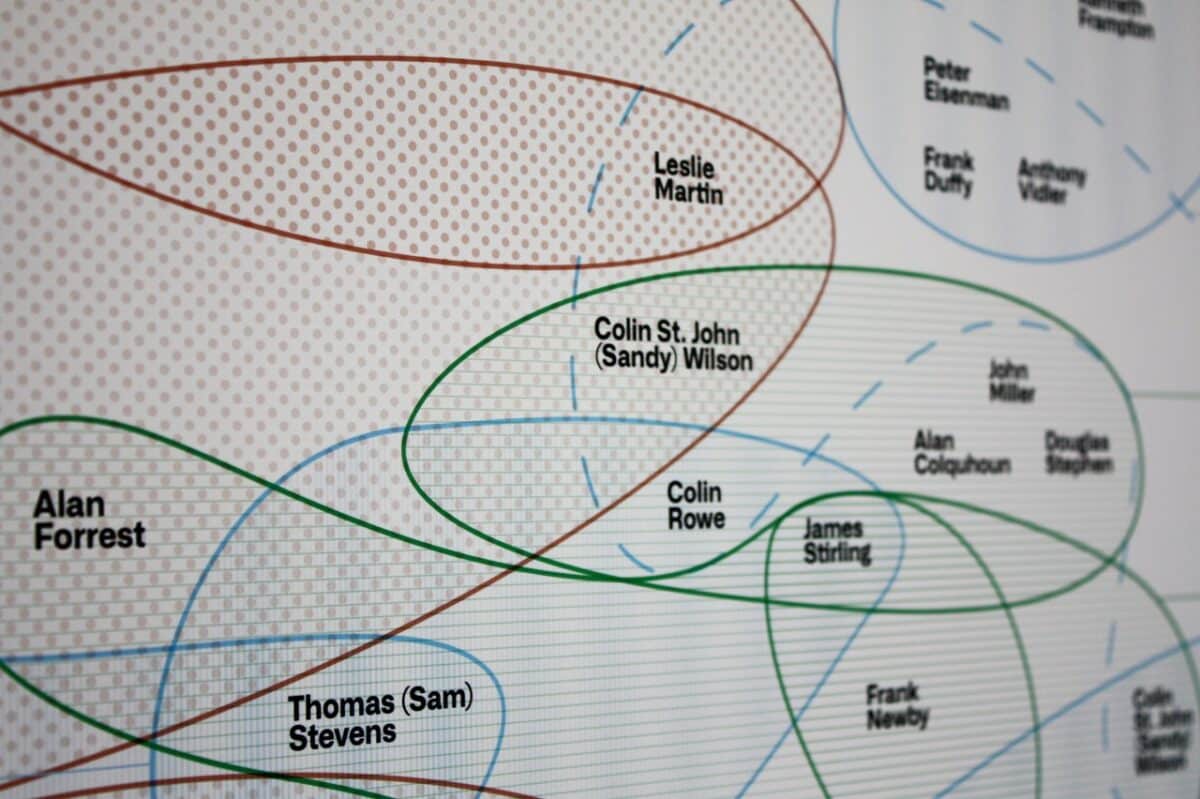

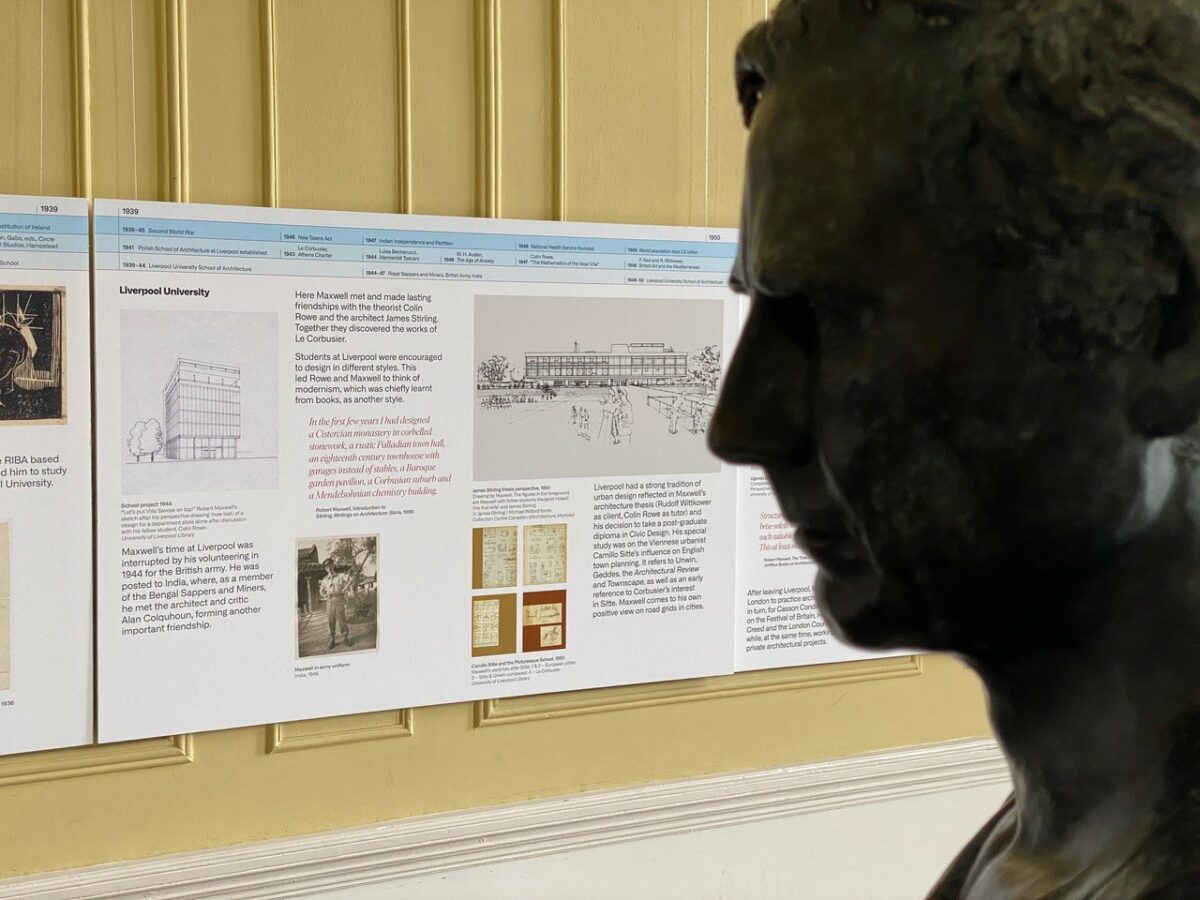

The opening of the exhibition and symposium about the architect Robert (Bob) Maxwell and the sculptor Celia Scott was held in the elegant home of the Irish Architectural Archive, at 45 Merrion Square in Dublin. The focus of the exhibition is a group of fourteen busts by Scott, which are arranged in the centre of two rooms on the first floor, occupying the space like a jury of Roman senators. On the walls surrounding them are panels of illustrations and text on the life of Maxwell, Scott’s husband, and each bust gazes at the section most pertinent to their own part and influence in it. The subjects of the busts are important architects, theorists and teachers, each of whom played a significant role in the architecture of the late-twentieth century. Some of them were also present in the flesh at the opening. The panels on the walls describe the work and life of Maxwell as architect, theorist, critic, author and teacher, and range from his early work at the LCC and the Festival Hall, to his teaching at the AA, the Bartlett and Princeton, and his critical writings about the work of his contemporaries.

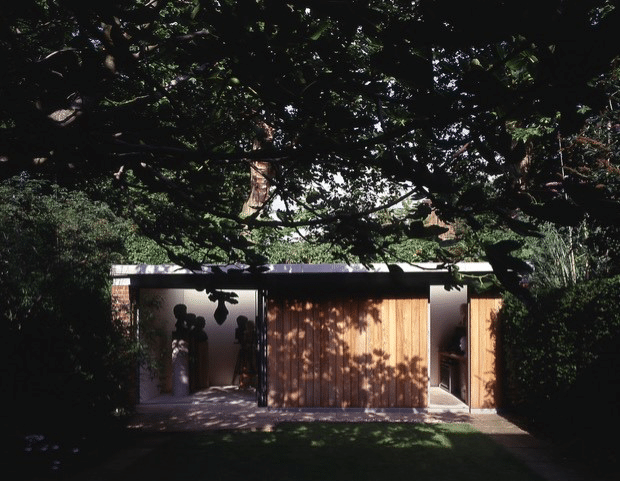

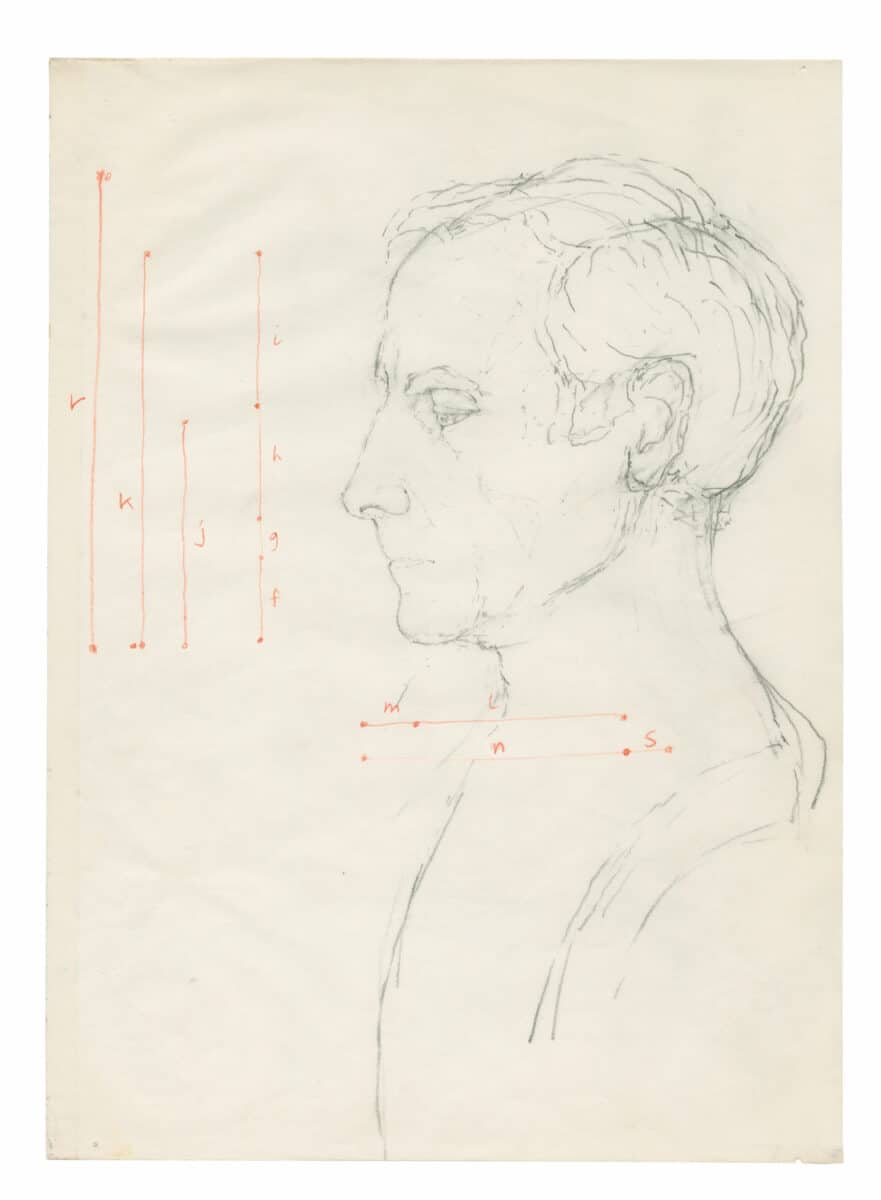

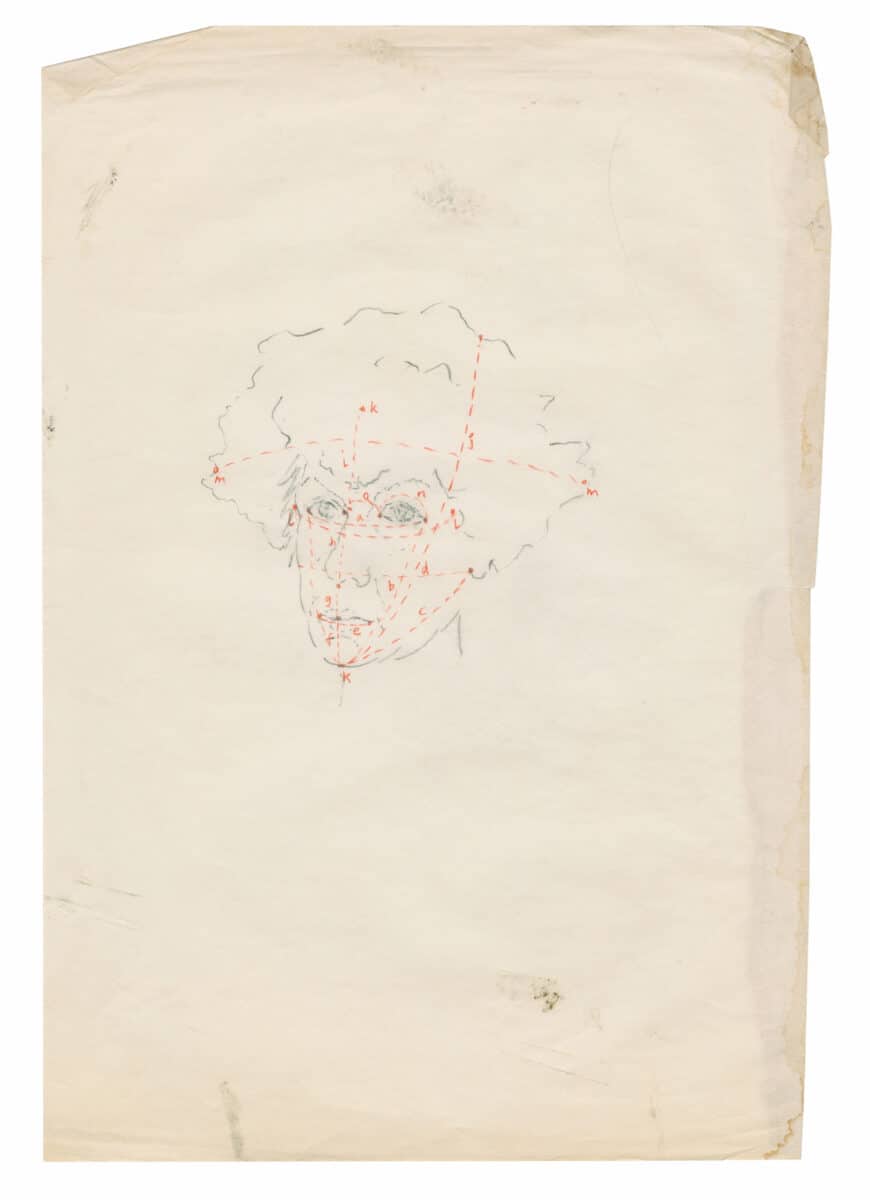

Scott is both an architect and sculptor, having trained as an architect at the Bartlett, University College London, (where she first met Maxwell) and practised as an architect in the UK and in the USA. Her career as a sculptor ranges over some forty years, although she gained an MA in Fine Art at the City and Guilds School of Fine Art as late as 2015, winning the Harriet Anstruther Prize there. Her work has been exhibited widely and internationally, with her sculptures being held in a number of public and private collections.

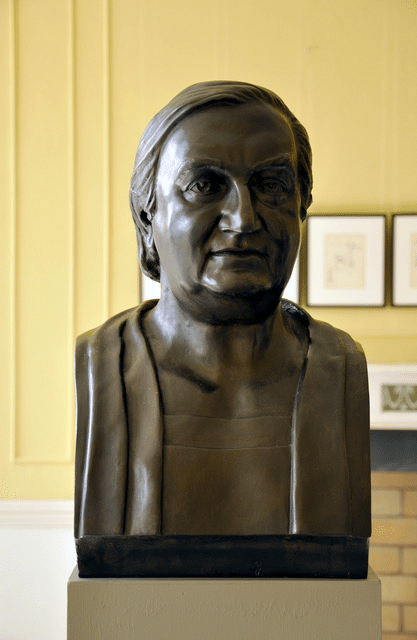

The busts are mostly at the same scale, close to life size, although that of Jim Stirling is slightly larger, cast in bronze and with a dominant presence, while that of Colin Rowe is much smaller, and is perched on the mantelpiece observing the scene like a small cat.* Some of the sculptures are dark, in bronze or with a bronze-like patina, while others are left in white plaster, with occasional faint colouring. The focus of the busts is very much on the character of the individual as evidenced in their facial expressions: they are classical in form, and there is no violent structural or abstract reinterpretation such as one might find with Picasso or Giacometti, nor are they particularly concerned with the tactile qualities of the clay they are formed with, like sculptures by Epstein or Schott. These are people who Scott knew well, and she has reproduced their solid likenesses with a very subtle emphasis expressing their character: for example, the head of M J Long is very straightforward and modestly but plainly challenging, as she was in life, while the head of Alan Colquhoun, the architect and philosopher, is sharply defined in a way that represents his thoughtful and critical nature. Leo Krier, the architectural polemicist, is very striking and has a slightly elongated likeness with a shock of snake-like hair like Circe’s.

At the opening, John Tuomey gave a very entertaining description of each of the individuals, remarking on the similarity of the head of Edward Jones to a rock star, and commenting on their influence on him and other students at University College Dublin as part of the ‘Flying Circus’ of visiting tutors there. The busts themselves remain silent and keep their own counsel, while gazing at the building designs on the walls and the chattering company around them, which included Jones, who spoke movingly of Maxwell’s kindly and inspiring teaching, where ‘he could find something not uninteresting to say about the most uninteresting project’.

Kenneth Frampton, an old friend, spoke about Maxwell’s architecture and suggested that his design for the Southwood Park flats in Highgate (which he designed while a partner at Douglas Stephen) deserved more prominent recognition by architectural historians. Maxwell’s contribution to architectural theory is well recorded in his publications: he remarked that ‘if belief has become questionable, what happens to conviction?’, as the religious conflicts in Northern Ireland where he was born left him with ‘a lasting abhorrence of all dogma and a desire to see both sides of an issue’. This is clearly an ideal attitude for a teacher in order to encourage students to consider alternatives, although there comes a point in the practice of architecture where you have to stick with what you have, which may have led to his concentrating on an academic career. He tackled difficult subjects, focussing on Roland Barthes’ concern for how a viewer’s expectation changed the perception of architecture, and approving the wonderful drawings of Leon Krier and the political ambitions of Maurice Culot as they addressed the urban whole rather than individual buildings. At the end of the symposium, the voice of Mike Gold (who had been following the proceedings on the internet) rang out, reminding us that another of Maxwell’s many talents was as a brilliant jazz pianist, who Gold had accompanied on the saxophone on many occasions.

The exhibition is an important tribute to a group of people who were significant players in British architecture (and beyond) in the latter half of the twentieth century and, perhaps more importantly, to those who have educated and influenced the architects of the first quarter of the twenty-first century.

Robin Webster

*In an email exchange between Celia Scott and the reviewer Robin Webster, Scott explained that: ‘Jim’s head is actually life-size, but probably looks larger because of the adjacent smaller heads. Alan Colquhoun had a small head, and I think probably Sandy’s head has become smaller than life-size. Just by way of explanation, I count myself a modern artist and the heads are meant to be ironic. I was playing games. They consciously do not show the hand of the artist, in order to show the difference between the sitters. I was using the bust form to reflect an idea about their public persona, so Leo’s head is done in strict 1850s style akin to his own passion for the architecture of that era. Jim was done as a German baron (he was doing a lot of work there and highly thought of in that country at the time), and the curved undercut of the front of the bust reflects the giant cornice at Stuttgart. Alan Colquhoun as Seneca.’

This is a hugely rewarding exhibition, relatively small in scale, installed in two first-floor rooms at the Irish Architectural Archive Dublin, but like the rooms grand in proportion, ambition, and extraordinary in its importance to an understanding of contemporary practice and thinking. The walls are hung with a continuous band of panels exhibiting the chronology, context, critical thought and inventiveness of Robert Maxwell’s long career. They invite a dialogue and an entry into diverse rich episodes of collective consciousness drawn into focus by Maxwell’s palpable presence – like a narrator of an epic novel see-sawing between object and subject. As a brief example while Maxwell was a student at Liverpool University School of Architecture, eyes and minds were keenly aware of European traditions of urbanism and ‘Civic Design’, and his study of the work of Camillo Sitte reverberate presciently now as then. There follows the post-war, post-Festival of Britain soul searching and emerging centres of radical practice at the London County Council and the receptive atelier of Douglas Stephen, through whose encouragement Maxwell strides between teaching and practice, with the former, gradually coming to dominate, culminating in his appointment at Princeton University, USA. Now begins the exhibition sequel: a surreal juxtaposition of fourteen heads sculpted by the very gifted eye and hand of Celia Scott, the exhibition’s curator, all caught at a moment in time, the cycle of which has already turned passed several lives. One finds oneself a participant in this theatre of contributors, set on herm-like pedestals, and in Scott and Maxwell’s own journey, one happily littered with deep friendships and convivial and generous encounters.

Eric Parry

Sweet Disorder and the Carefully Careless: Ideas, Faces and Places is on display at The Irish Architectural Archive until 25 November 2022.

Eric Parry is founder and principal of Eric Parry Architects.

Robin Webster is emeritus professor, Scott Sutherland School of Architecture at The Robert Gordon University, and partner at Cameron Webster Architects.