Take One: Colin St John Wilson, MJ Long and Eric Parry on the British Library

– Editors

Take One is a collaboration between Drawing Matter and the Architects’ Lives oral history project run by National Life Stories. Each episode pairs a drawing or visual element with a short audio extract, showing the image alongside the voice of its creator or an informed commentator. The audio extracts are taken from life story recordings created by National Life Stories at the British Library alongside sister projects with a range of people. Many of these recordings can be heard online.

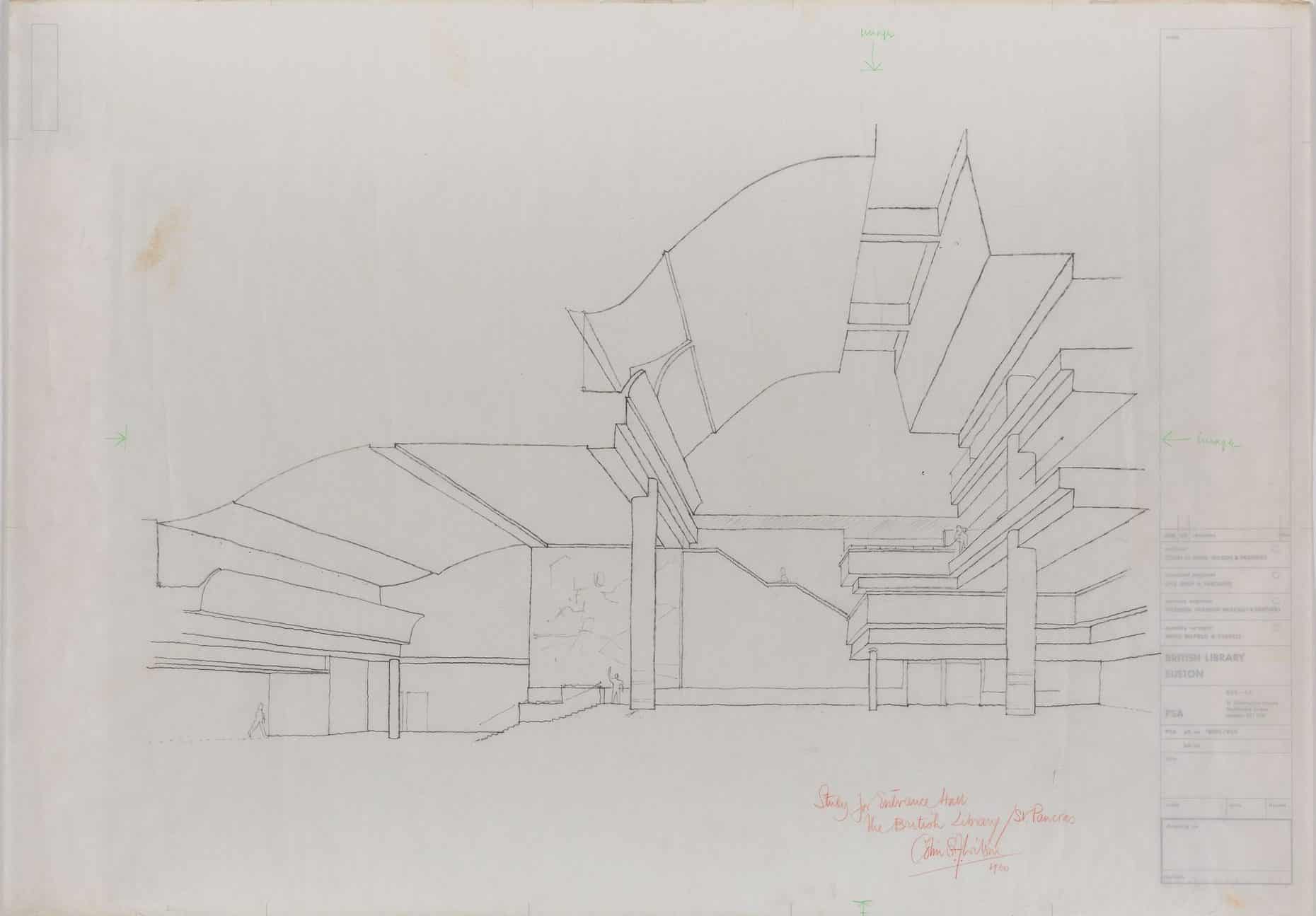

Designed by Colin St John Wilson and MJ Long, the British Library is arguably the most important building to be completed in Britain in the twentieth century. When it finally opened in 1997 it was certainly the largest – comprising two million square feet, over 14 floors (nine above ground and five more that run 24 metres below) and bringing together for the first time the collections of the British Museum Library, which had been dispersed across London since its inception in 1753. Looking back, Wilson described the library as his ‘30-year war’, which started in the early 1960s, when he and then-partner Leslie Martin designed a building for the original seven-acre site in Bloomsbury. After countless redesigns the Bloomsbury location was scrapped and a plot in Euston was identified. Wilson, working with Long after Martin’s retirement, developed the design for what – thanks to budget issues, delays, changes in politics, attitudes and matters of taste – was for a time every critic’s favourite building to hate. While it was under construction the Prince of Wales, likened the reading room to an academy for secret police, not surprisingly preferring Sydney Smirke’s original Pantheon-inspired reading room at the British Museum. But the new design by Long elegantly reconciled both the institution’s myriad parts and the awkward site at Euston with a soaring entrance hall and the six-storey central glass tower, which holds the 65,000 books that make up the King’s Library. Wilson maintained that if he could not design a cathedral, then a library would be the next best thing, and Antonello’s painting of St Jerome, the patron saint of libraries, which hangs at the National Gallery, was an image he returned to throughout the project:

Ensconced in a timber shell raised four steps above the cold tiled floor, the scholar is enveloped in a purpose-made aedicule of bookshelf, ledge and desk like an organist’s console. The whole structure forms a frame of attention focused upon the act of reading: and in its turn this delicate barque is enveloped within a high-vaulted structure of stone. It is the very embodiment of intense silent concentration in a hierarchy of space and a palette of materials each of which responds to purpose by its sale, position, texture and orientation to light for this fortunate scholar.

The following short clips have been extracted from oral histories with Wilson and Long, shortly before and after the building opened; and Eric Parry, who as a tutor at Cambridge used the British Library as a case study and brought students to the building when it was under construction.