The Drawing as Actor

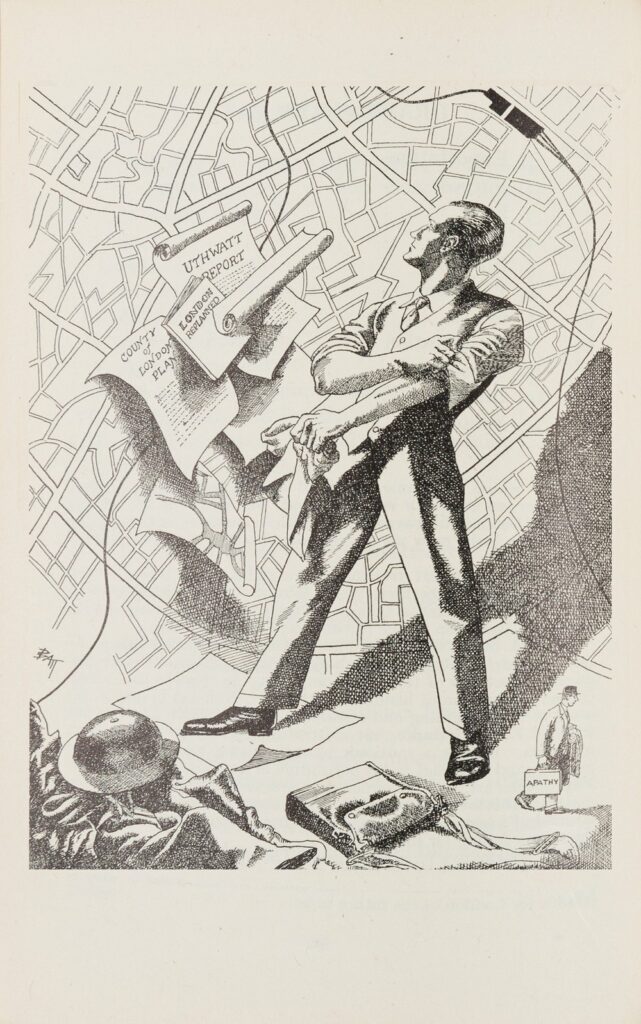

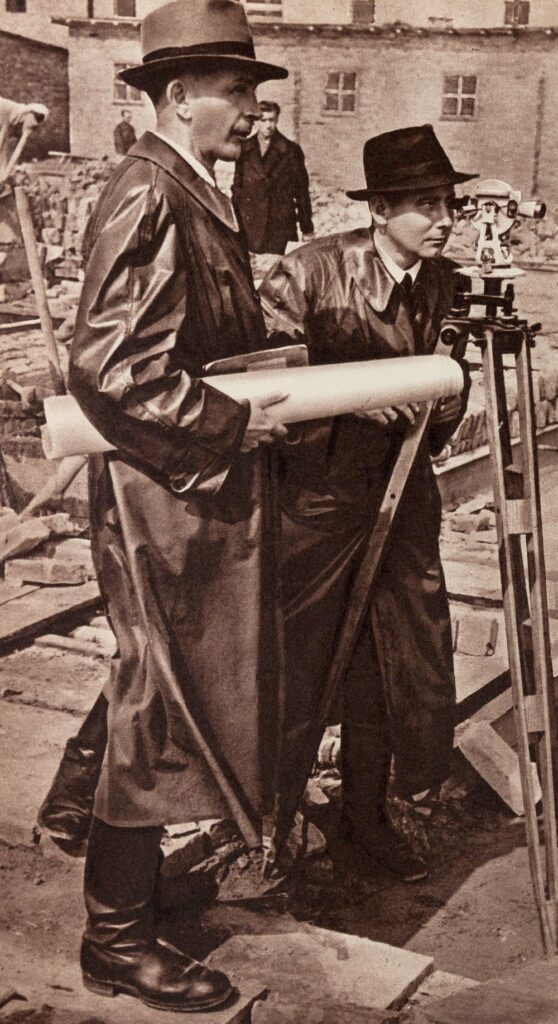

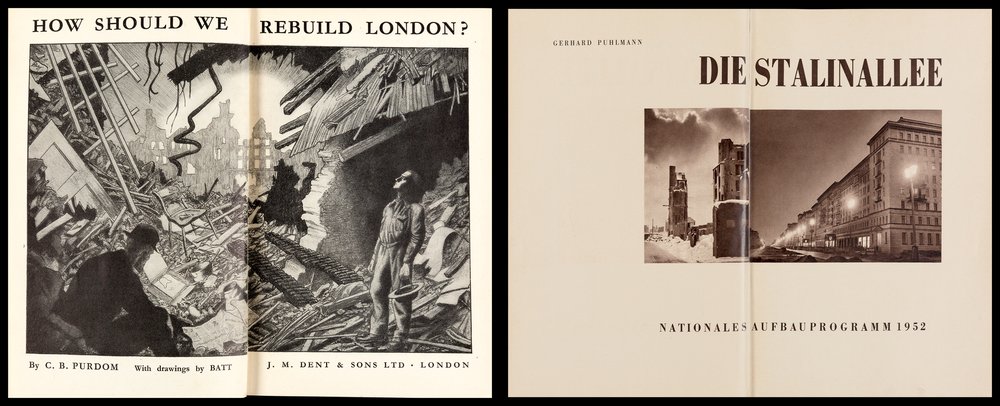

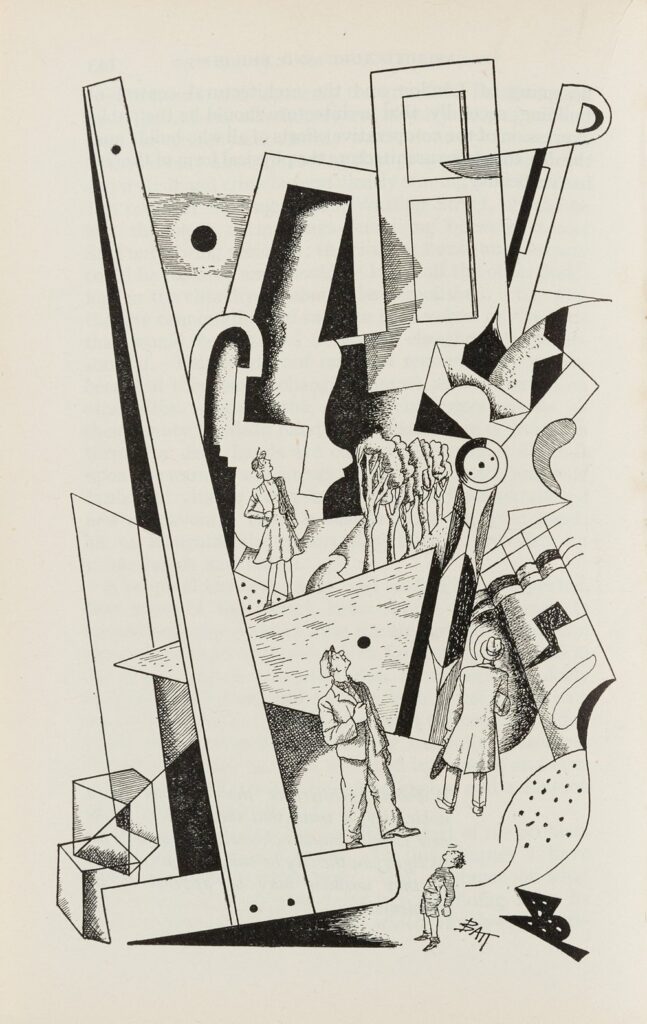

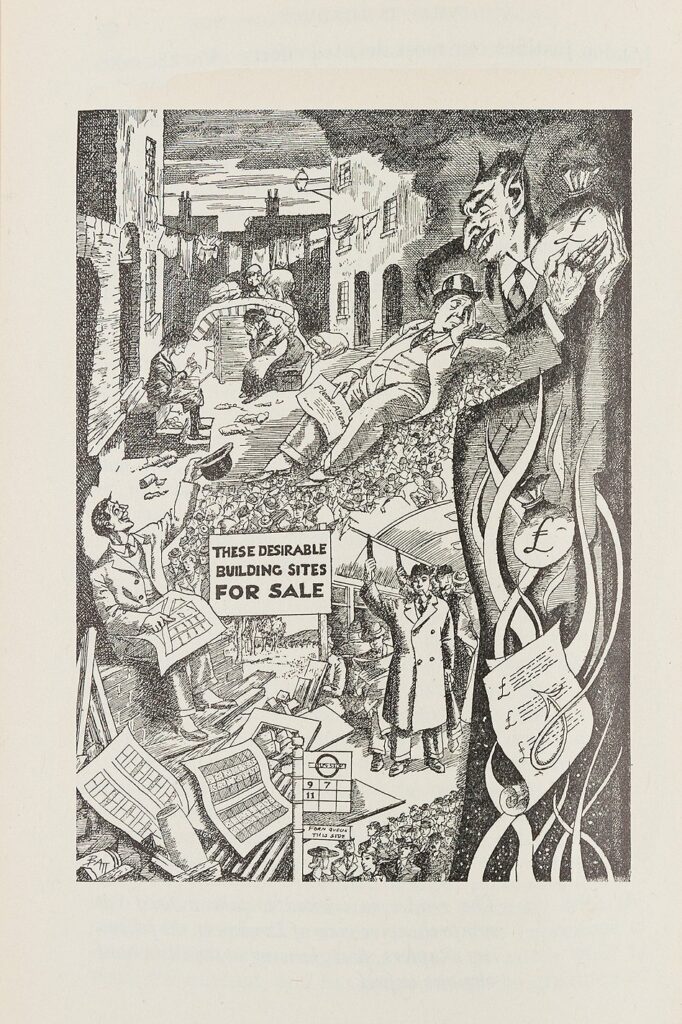

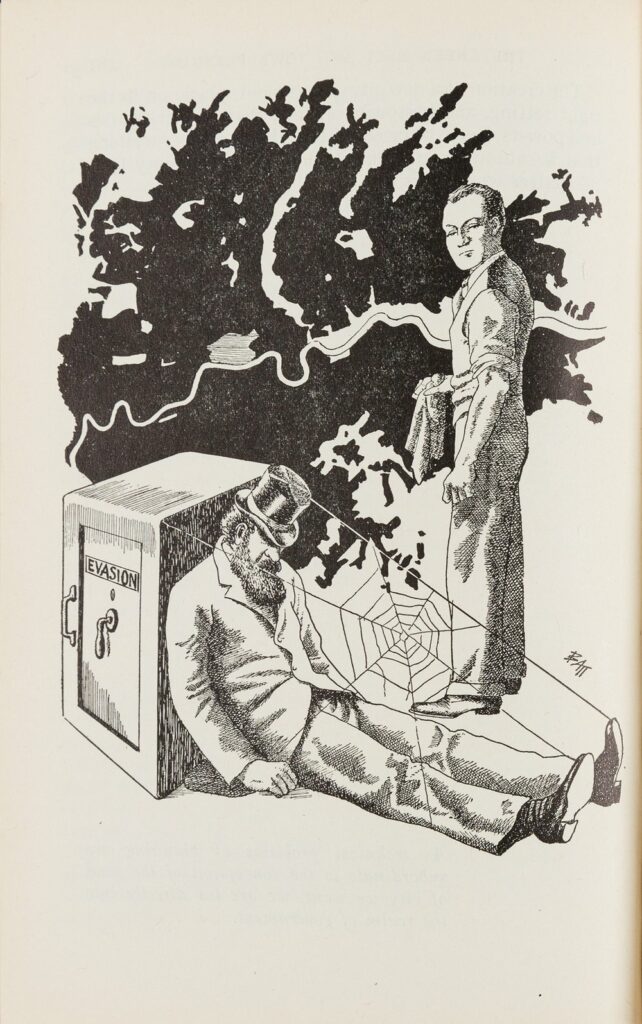

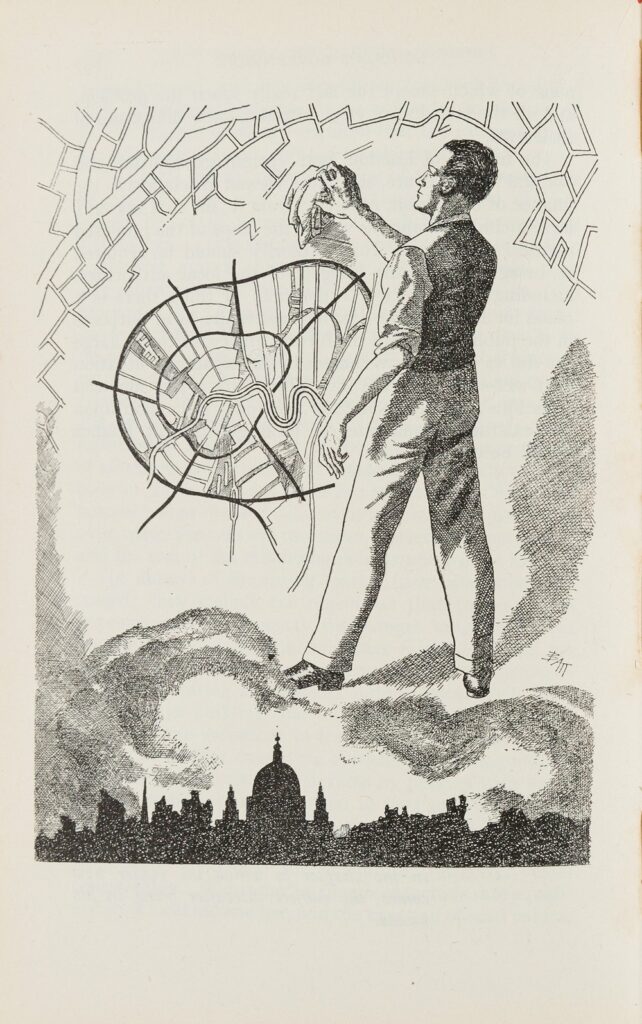

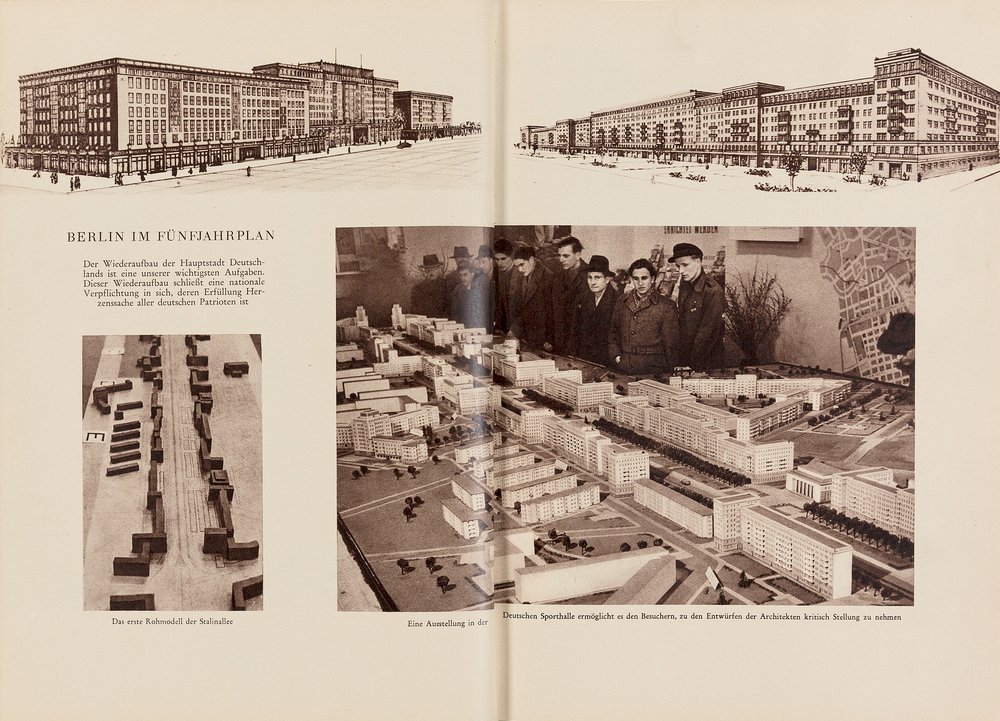

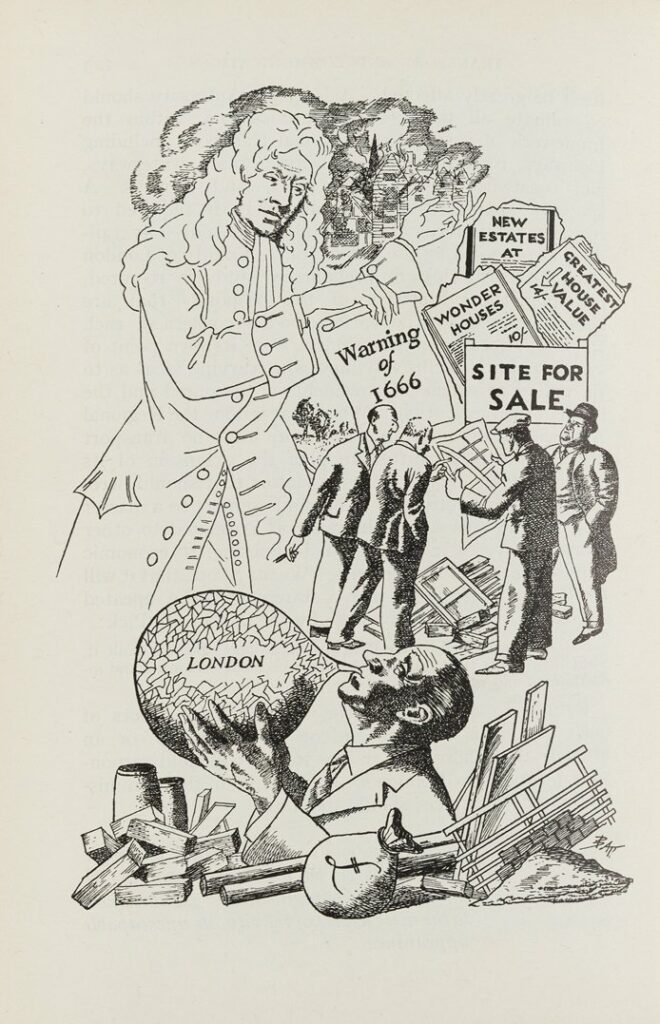

In two publications about post-war reconstruction, How should we rebuild London? (J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd, London, 1945) and Die Stalinallee Nationales Aufbauprogramme (Verlag Der Nation Berlin, 1952), the planning ferment in London and Berlin becomes a performance in itself, revealed through the choice of the media and subjects which they each adopt for illustration. For London the illustrations were graphic with drawings by ‘Batt’, Oswald Barrett, who used drawing as a freedom to dream sentimentally about the agency of the planner. For Berlin they were photographic: Gerhard Puhlmann was able to pose his photographs with all the authority of the DDR propaganda machine at his back. Both were of course handicapped by the absence of buildings that were substantial enough to be drawn and photographed.

How should we rebuild London? was written by C. B. Purdom in 1945 in the closing months of the war. To the author’s chagrin it was published after the County of London Plan, which it had sought to influence, had been completed. The text is an undigested mix of planning doctrine and 1930s xenophobia. The author lived all his adult life in Welwyn Garden City, which he helped to create and direct. In the book, he describes the villages of England as ‘neighbourhood-unit conceptions’ and the people of Southwark, which he wanted to rebuild from the ground up, as ‘real Londoners, with practically no Jews or foreign-born inhabitants’.

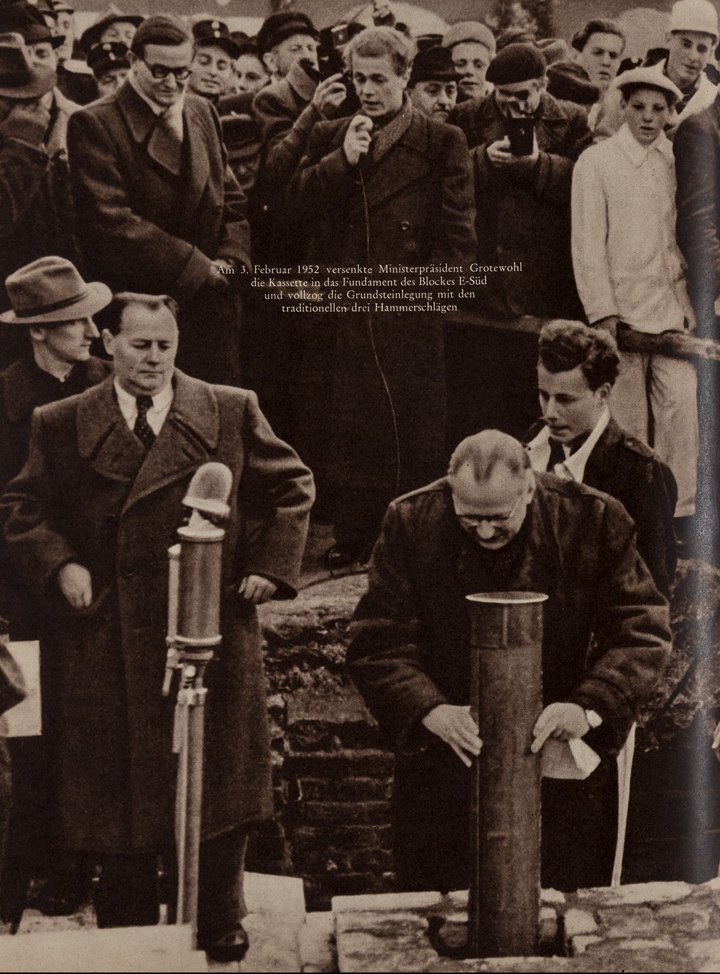

Die Stalinallee was published in 1952 but seems to have been reissued under an identical imprint in subsequent years with a new dust jacket and photographs of the buildings as they were topped out, as though the first Five Year Plan had been completed in less than eighteen months.

Ambitions

How should we rebuild London? : ‘Without architecture there cannot be a noble city; only in its light can the city be envisaged as a whole so that wisdom may be applied to its problems…’

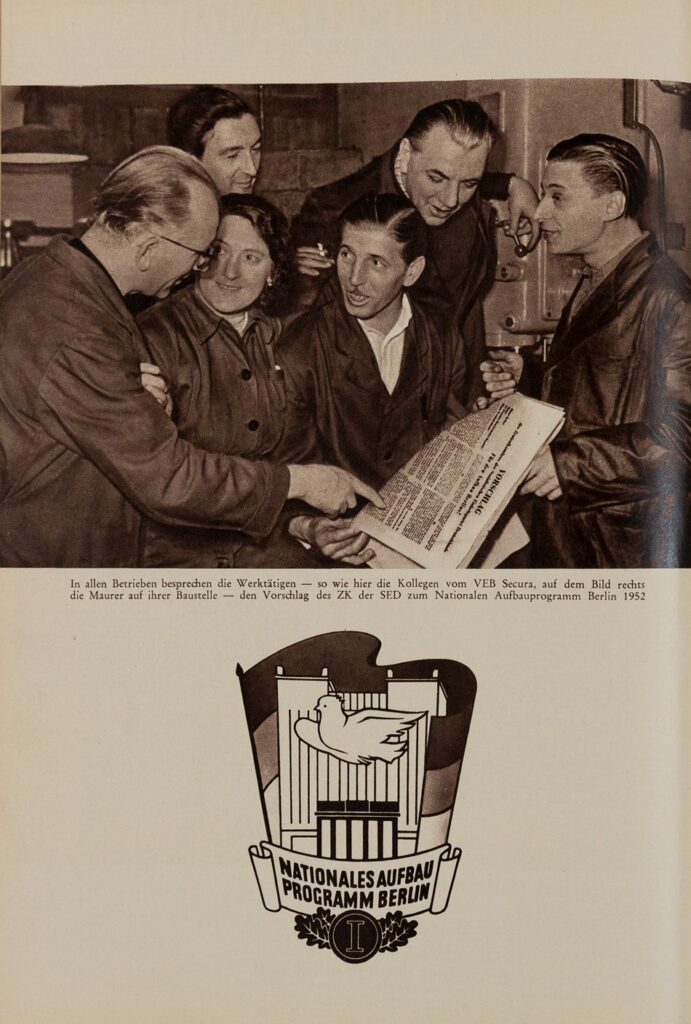

Proclamation of the National Committee for the Reconstruction of the German Capital, addressed to all Germans, East and West: ‘With the People’s Movement for the National Construction Programme we are entering a new phase in the history of our Nation’s struggle for independence. Every German shall be able to claim with pride to have been involved.’

Purdom’s London

‘London Rebuilt: London requires to become a perceptual object, visualised in memory and imagination, and interpreted in terms of human life. By visualisation, thought, and discussion, and by the exchange among its citizens of mental as well as physical objects, London can be transformed.’

‘The reader is invited to take a brief but comprehensive view of London in the following chapters, first glancing at the city’s most obvious aspect… London as a Home’

‘London’s Government: As technical problems of planning are subordinate to the conception of the kind of city we want, we are led directly into the realm of government’

Puhlmann’s Berlin

‘The reconstruction of the German capital is among our most important tasks. It is a duty keenly felt by all German patriots.’

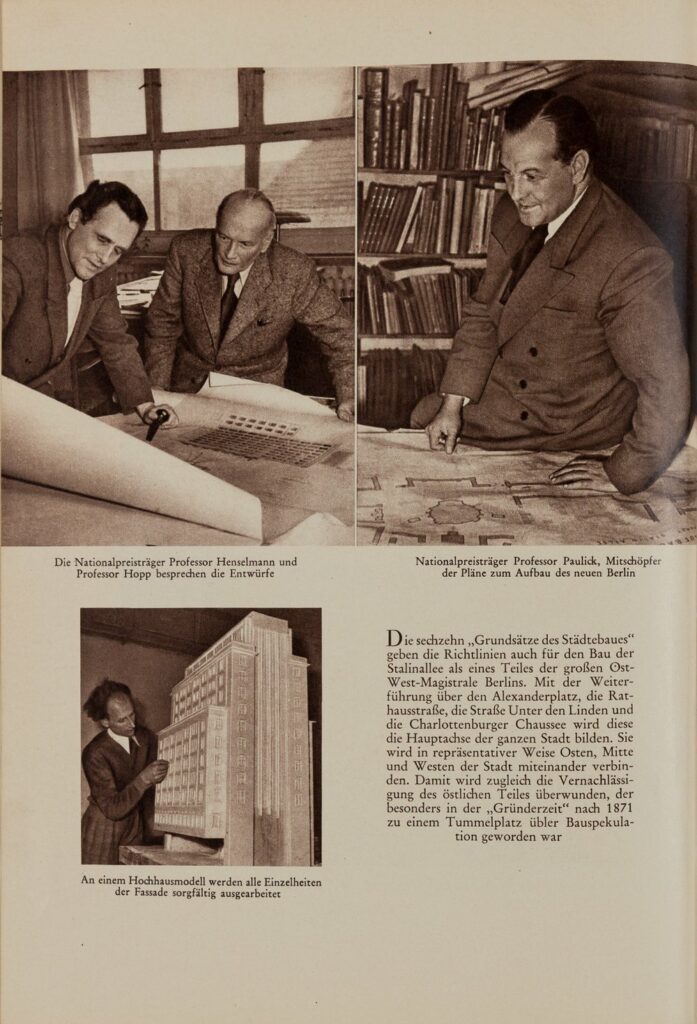

Right: An exhibition at the Deutsche Sporthalle offers visitors the opportunity to comment critically on the architects’ drafts

‘The “sixteen principles of urban design” also guide the construction of Stalinallee, which will form part of Berlin’s great Ost-West-Magistrale. Running through Alexanderplatz, Rathausstraße, Unter den Linden and Charlottenburg Chaussee, connecting east, centre and west, it will form the definitive axis of the whole city. This also means new attention to the formerly neglected eastern part of the city, where speculative building at its worst was once rampant, particularly during the Gründerzeit years from 1871.’

Upper right: National Prize-winning architect Professor Paulick, co-author of the plans for the construction of the new Berlin

Below: Every detail of the facade of a high-rise block is worked out with care using a model

Arm in arm

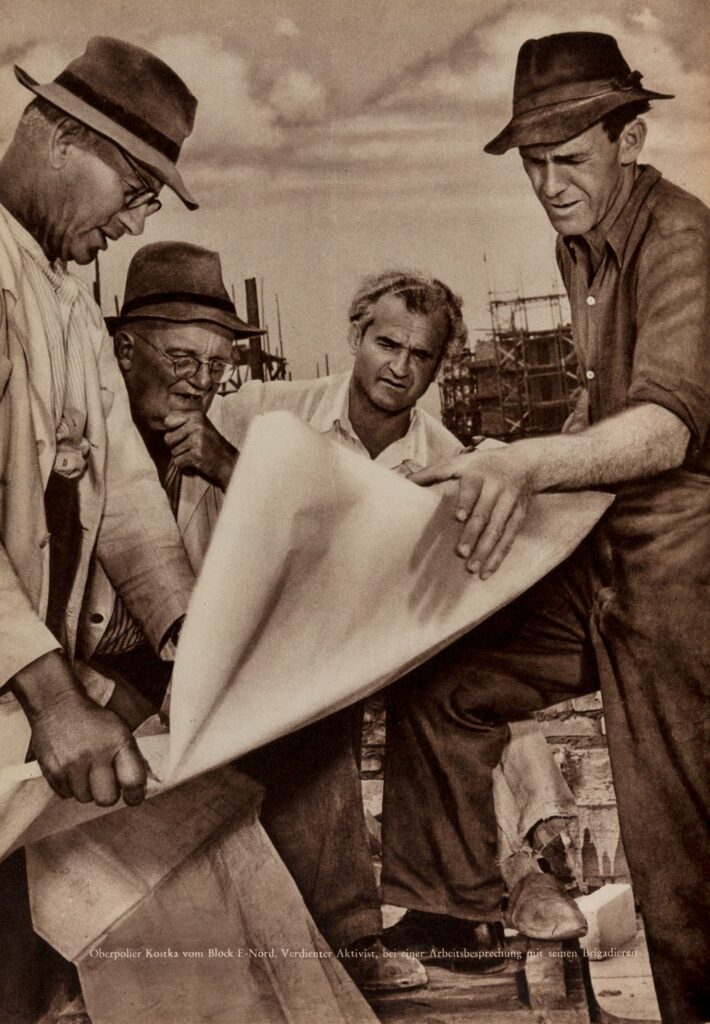

Each image here is its own careful construction, even as it is presented as enthusiastic argument or innocent reportage. In the illustrations of both books the architectural drawing, at once a stage prop and a leading actor, becomes the powerful stand-in for the yet-to-be-built; and, caught in the limelight, the drawing assumes multiple roles in the drama of reconstruction.

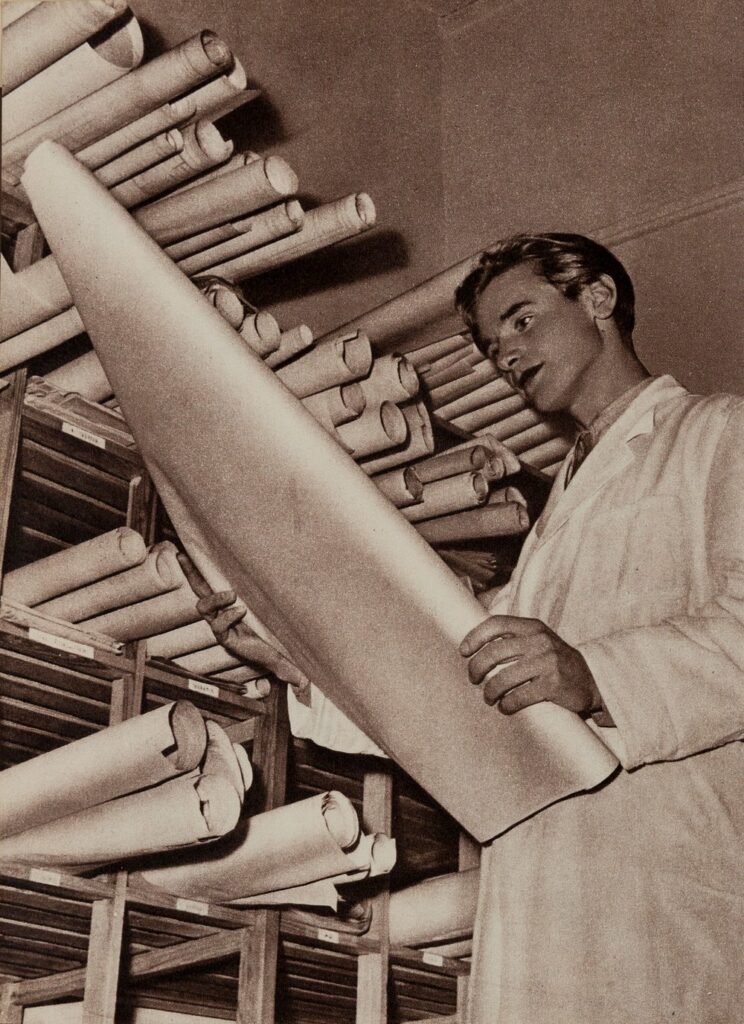

Sometimes it is the act of drawing which itself becomes the literal proxy for the dreams the drawings encapsulate. We are shown technical drawings that are active agents of discussion or execution as they are consulted by politicians, professionals and construction teams; or, as viewed instead by the public, symbols of consensus and inclusion in a destroyed world.

Within these pages the dreams come full circle. Politicians, planners, architects, engineers, construction workers, the homeless and the dispossessed, can march arm in arm down wide new streets that exist only on the sheets of paper they clutch.

The production of this short article involved too many thoughtful collaborators for them to be gratefully acknowledged individually. They know who they are. Niall Hobhouse