Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild at Waddesdon

– Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild

The following extract, a personal account by Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild, describes the imaginary and real processes of constructing and maintaining a country home, from the ground up, in late-19th-century England. Written for the Red Book in 1897, a family album of sorts, it is one of the key sources relating to the creation of Waddesdon and evidences the Baron’s dialogue with the French architect Hippolyte Alexandre Destailleur, drawings by whom are held by Drawing Matter and the Kunstbibliotek Berlin.

In the autumn of 1874 I purchased from the Duke of Marlborough, by private treaty, his estate of Waddesdon and Winchendon, which had been put up for sale at Tokenhouse Yard in the spring of the year but withdrawn as the reserve price had not been reached. It then consisted of 2700 acres, to which I have since added about 500 more. I had been looking out for a residential estate for some time, and could I have obtained one I should not have acquired this property, which was all farm land, arable chiefly, with neither a house nor a park, and, though comparatively near London, was at a distance of six miles from Aylesbury, the nearest railway station. But there was none other to be had; there was not even the prospect of one coming into the market, and I was loth to wait on the chance. So I took Waddesdon with its defects and its drawbacks—of which more hereafter—perhaps a little too rashly. I was buoyed up with illusions and beguiled by the belief that within four years it would be connected with Baker Street by a direct line of railway, the first sod of which had not yet been turned. This much could be said in its favour: it had a bracing and salubrious air, pleasant scenery, excellent hunting, and was untainted by factories and villadom.

As soon as the contract was signed I set out for Paris in quest of an architect, and decided on the late M. Destailleur, whose father and grandfather had been the architects of the Dukes of Orleans, while he himself had risen to fame by his intelligent and successful restoration of the Château of the Duc de Mouchy. M. Destailleur accompanied me back to England to choose the site for the house. This being settled, he left me fully supplied with instructions, while M. Lainé, a French landscape gardener, was bidden to make designs for the terraces, the principal roads and plantations. It may be asked, what induced me to employ foreign instead of native talent of which there was no lack at hand? My reply is, that having been greatly impressed by the ancient Châteaux of the Valois during a tour I once made in the Touraine, I determined to build my house in the same style, and considered it safer to get the designs made by a French architect who was familiar with the work, than by an English one whose knowledge and experience of the architecture of that period could be less thoroughly trusted. The French sixteenth century style, on which I had long set my heart, was particularly suitable to the surroundings of the site I had selected, and more uncommon than the Tudor, Jacobean, or Adams, of which the country affords so many and such unique specimens. Besides, I may mention that M. Lainé was called in only after Mr. Thomas, the then most eminent English landscape gardener, had declined to lay out the grounds for reasons he did not deign to divulge.

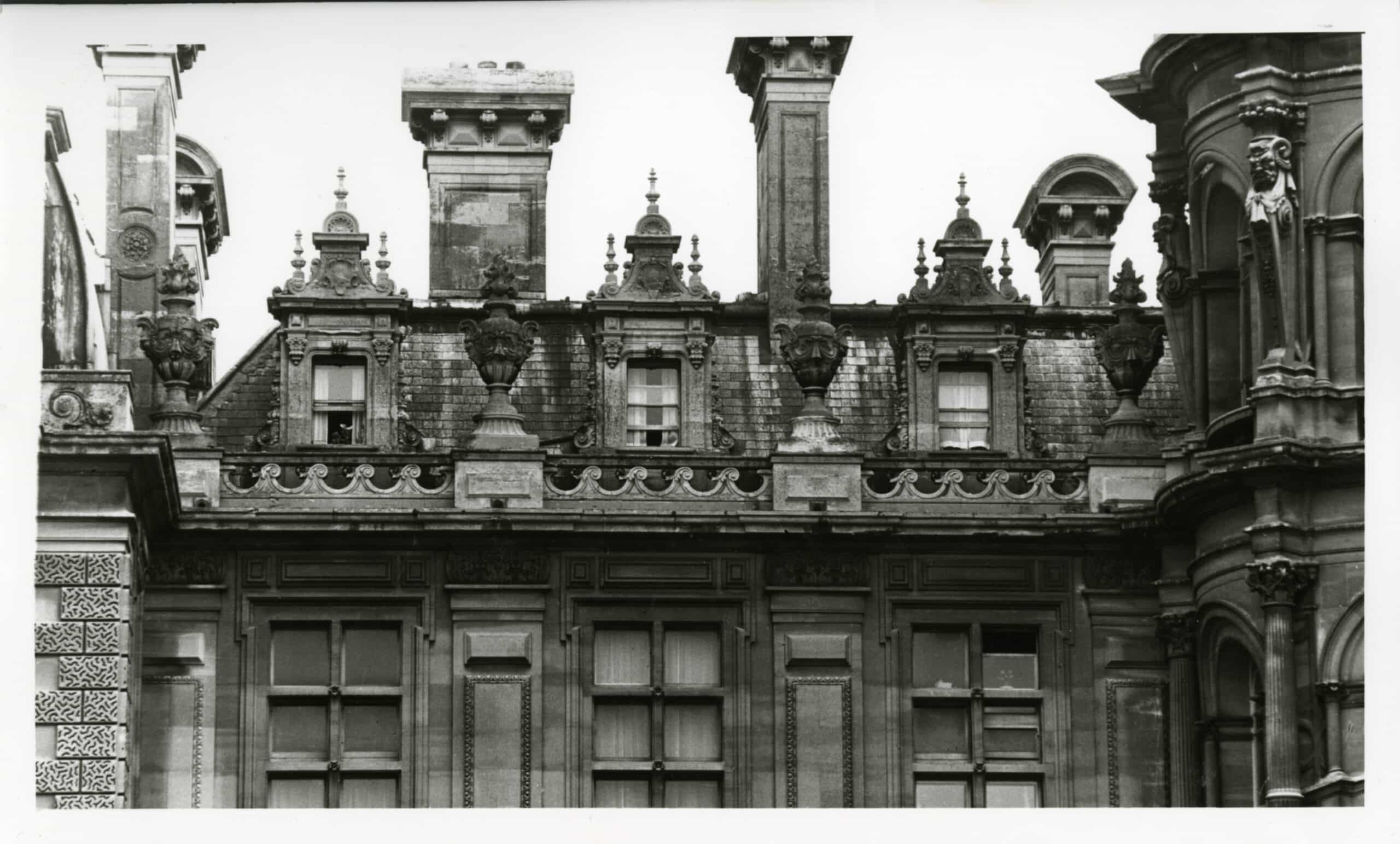

By the side of the grand châteaux of the Touraine, Waddesdon would appear a pigmy. The Castle of Chambord, for example, contains 450 rooms, the smallest of which would dwarf the largest of Waddesdon. But its main features are borrowed from them; its towers from Maintenon, the Château of the Duc de Noailles, and its external staircases from Blois, though the latter, which are unglazed and open to the weather, are much more ornate. Though far from being the realisation of a dream in stone and mortar like Chenonceaux, M. Destailleur’s work has fairly fulfilled my expectations.

M. Destailleur was a man of the highest capacity in his profession. He was a purist in style, painstaking, conscientious, and of the most scrupulous honesty. During the eighteen years of my relations with him there never was the smallest difference between us. But he was dilatory and unpractical. He had not the faintest conception of the needs of a large establishment, sacrificed the most urgent household requirements to external architectural features, and had the most supreme contempt for ventilation, light, air, and all internal conveniences. This, perhaps, need not have surprised me, for he and his numerous family lived huddled together in a small and musty house in a dingy back street which I never entered without a shudder. It took me many an hour to convince him that ladies need space for their gowns and their toilette, and men want rooms in which they can move at their ease and perform their ablutions. The delay in the first start, however, was only partly his fault. He submitted a plan to me at the end of a year on a scale of such grandeur that I begged him to reduce it, and another long year was spent on the preparation of a second and more modest proposal. This I sanctioned, though it did not quite satisfy me. ‘You will regret your decision,’ he said to me at the time, ‘one always builds too small.’ And he prophesied truly. After I had lived in the house for a while I was compelled to add first one wing and then another; and a greater outlay was eventually incurred than had the original plan been carried out, not to speak of the discomfort and inconvenience caused by the presence of the workmen in the house. Though more picturesque the building is less effective, and while spreading over as much ground it is less compact and commodious.

Lodge Hill, as the small but steep hill on which it stands is called—its highest point being 614 feet above sea-level—commands a panoramic view over several counties. On the north is the long range of the Chiltern Hills; on the south-west the Malvern Hills loom in the far distance; on the west is Wootton, the former abode of the Grenvilles, a corner of which peeps out of a dense mass of woodland. Towards the north the eye travels over a boundless expanse of grass-land, and on the east the Vale of Aylesbury winds along. Lodge Hill when first taken in hand was a misshapen cone with a farmhouse on its top, to which a rough track for carts led direct from the village. Often when hunting I had noticed its singular formation—the result probably of a volcanic eruption—and its fine hedge-row timber. When it came into my possession nearly all the timber had vanished, and but for a few hollies round the farmhouse there was not a bush to be seen, nor was there a bird to be heard; but luxuriant crops of wheat and beet told of the richness of the soil. A deep gash was made in its side by a limestone quarry which proved most useful in the construction of rockeries, and has since been converted into a basin and fountain.

The estate was bought in 1725, three years after the death of the great Duke, by Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, from the trustees of the Duke of Wharton, of whose romantic and eccentric career we may well regret having such scanty records. The residence of the Whartons, who had inherited the land from the Goodwins to whom it had been granted in 1623 by the King, stood about two miles south from Lodge Hill, near the village of Upper Winchendon, and at the end of an imposing avenue of elms which led up hill and down vale to Waddesdon. Its gardens and kennels were famous, and the whole of the property was studded with fine timber. Lodge Hill was outside the boundaries of the park, and had always been let for farming, but in the middle ages a monastery flourished close to the village of Waddesdon, where traces are still to be seen of its fishponds. Since the days of the famous Duchess, the Dukes of Marlborough had never set foot on the domain, except on one occasion, when the grandfather of the present Duke spent a brief hour in the village when the church was reopened after its restoration. Having been bought as an investment, the estate was only valued thereafter for the grist it brought to the mill, and was abandoned to the most cruel neglect. The land on the roadsides was encroached upon and built over; footpaths were made in every direction—the most objectionable of which, however, there being then no Parish Council in existence, I was able to close; short-sighted agents cut up the farms into small fields, and felled most of the timber. Stately avenues of elm, chestnut, and beech, all of which I have replanted, were ruthlessly cut down. Even the small Winchendon Wood was doomed and would have gone with the rest had I not stepped in in the nick of time.

Of the house of the Whartons only a wing of the offices, which was my own abode during the progress of the works on Lodge Hill, and is now occupied by my bailiff, was allowed to remain; while a high-road leading from Aylesbury to Thame has been constructed past its windows, precluding the possibility of erecting a new mansion on the old site. The gardens, which may still be identified by the lines of their terraces, have long disappeared, and when I first saw them, were covered with sheds, squalid cottages, and pigsties, presenting an indescribably repulsive appearance.

Nestling in the wood and fronting Lodge Hill stands an ancient cottage, round which hangs a curious tale. It was said to have once been a kind of Rosamond’s Bower, where a Lord Wharton secreted a French lady, deeming her secure there from the jealous eyes of his wife. But Lady Wharton discovered her rival, whom she soon got rid of by poison. I attached little credence to this story. But recently, when the crypt of the Winchendon Church was being restored, a coffin was found among the tombs of the Whartons with a brass plate bearing the inscription, ‘Madame B.,’ and the date corresponded with that assigned to the French lady’s death by tradition, which was thus—in part, at least—vindicated.

As soon as the architect, the landscape gardener, and the engineers had settled their plans, we set to work, but at the outset were brought face to face with a most serious consideration. This was the question of the water supply, as the few springs in the fields were not to be relied on in a drought. The Chiltern Hills fortunately contain an inexhaustible quantity of excellent water, which an Aylesbury Company works with much skill to the advantage of the immediate neighbourhood and profit to its shareholders. Not a moment was lost in coming to terms with the Company, laying down seven miles of pipes from the county town to the village and thence to the projected site of the house, and building a large storage tank in the grounds. This subsequently proved insufficient for our wants, as one dry summer the water supply failed, and but for the Manager’s energy, who sat up all night at the Works sending us up water, we should have been compelled to leave the next day. To obviate the recurrence of a similar difficulty another and a larger tank was constructed.

Then we had some trouble with the foundations of the house. The part of the hill we had selected for its site consists of sand, and the foundation after having been proceeded with for some months proved not to have been set deep enough, as they suddenly gave way. The whole of the brick-work had then to be removed and thirty feet of sand excavated until a firm bottom of clay was reached. I now began to realise the importance of the task I had undertaken. But the difficulty of building a house is insignificant compared with the labour of transforming a bare wilderness into a park, and I was so disheartened at first by the delay and the worry that during four years I rarely went near the place. Slowest and most irksome of all was the progress of the roads, on which the available labourers of the neighbourhood were engaged, supplemented by a gang of navvies under the direction of Mr. Alexander, a London engineer, and M. Lainé. The steepness of the hill necessitated an endless amount of digging and levelling to give an easy gradient to the roads and a natural appearance to the banks and slopes. Landslips constantly occurred. Cutting into the hill interfered with the natural drainage, and, despite the elaborate precautions we had taken, the water often forced its way out of some unexpected place after a spell of wet weather, tearing down great masses of earth. Like Sisyphus, we had repeatedly to take up the same task, though fortunately with a more permanent result. The stone for the house, which came from Bath, and most of the bricks, which came from all parts of the country, were conveyed on a temporary steam tram from the railway direct to the foot of the hill, up which the trucks were drawn on rails by a cable engine. Other materials for the building, as well as for the farmsteads, cottages, and lodges, and the trees and the shrubs, had to be carted some miles by road. Percheron mares were imported from Normandy for this purpose, and they proved most serviceable, for though less enduring they travelled faster over the ground and were much cheaper than Shire horses. They have since doubled in price. When worn out they went to the stud.

These horses were employed principally in connexion with the cartage of large trees which were brought from all parts of the neighbourhood, and for the moving of which on to the highways the telegraph wires had to be temporarily displaced. They were transplanted with huge balls of earth round their roots, and were lowered into the ground by a system of chains, having been conveyed to the required spot on specially constructed carts, each drawn by a team of sixteen horses. The trees answered their purpose for the time, for they quickly clothed and adorned the bare hill. But if I may venture to proffer a word of advice to any one who may feel inclined to follow my example—it is to abstain from transplanting old trees, limes and chestnuts perhaps excepted, and even these should not be more than thirty or forty years old. Older trees, however great may be the experience and skill of the men engaged in the process, rarely recover the injury to their roots, or bear the change from the soil and the climatic conditions in which they have been grown. Young trees try your patience at first, but they soon catch up the old ones, and make better timber and foliage.

But much that was of far greater moment had to be accomplished before any appreciable show was made. Small properties that ran into the estate on all sides had to be obtained from a variety of owners, of whom some were unwilling to sell, others held their land by a complicated title, and others again had let it on long leases. Tenants had to be dispossessed and otherwise provided for; a large silk factory and three public-houses had to be acquired; the dilapidated homesteads pulled down and rebuilt elsewhere; over 150 cottages and a huge flour-mill purchased and demolished to make room for the proposed improvements and then rebuilt further off; the whole of the land had to be drained, interminable double hedgerows dug up, ridges and furrows levelled, the arable fields sown with grass, and, last though not least, extensive coverts and shrubberies had to be planted.

It would be wearisome to give a more minute account of the protracted and vexatious, nay exasperating negotiations which attended the purchase of these small properties, or to enter into a detailed description of the various works which had to be carried out, and which at one time seemed hopeless of final accomplishment. The removal of one nuisance frequently opened out a vista to another which it became equally imperative to sweep away, and the acquisition of one plot of ground usually necessitated the purchase also of the plot adjoining it. In the same way, the planting of a covert or a shrubbery on one naked spot showed up the bareness of its surroundings which had then also to be planted; and as we kept on extending the boundaries of the park fresh alterations were constantly demanded. Even when after many years we had virtually come to an end of our labours the park could not be enclosed in a ring fence, for on one side some of the Duke of Buckingham’s land came to the very edge of the principal drive, and on the other, thirty acres, which belonged to a tenant farmer, stood in a direct line with the terrace. Neither the Duke nor the farmer would hear either of purchase or exchange. ‘I am anxious for this ground of yours,’ I once said to the Duke, while on a visit to Wootton; ‘for were you to put up buildings on it my view would be spoilt.’ ‘Come,’ he replied with a smile, and he took me to a window on the first floor of his house. ‘There; look out,’ he said, pointing to the spot; ‘were you to build on it, and you might, my view would be spoilt.’ After the Duke’s death his successor, Lord Temple, proved more tractable. I owe the possession of the farmer’s thirty acres to the passing of the Parish Council’s Act. They skirt the high road, and if turned into allotments or small holdings would have been a terrible eyesore. It was most unlikely that the Parish or County Council would use their compulsory powers for this object, the village being sufficiently provided with allotments; but on my hinting to the farmer the possibility of the danger which threatened him on that score he at once closed with my offer.

In 1880 I first slept in the so-called ‘bachelor’s wing’, and in 1883 in the main part of the house. We had a grand house-warming in the month of July of that year, though the stables were not yet built, and the horses and carriages we required had to be accommodated in tents and in the village inns. The stables were built in the following year from plans made by my stud-groom, my builder, Mr. Conder—than whom I have never met a more trustworthy business man—and myself. Only the elevations were designed by M. Destailleur, and no other architect was ever called in for the alterations and additions subsequently carried out at Waddesdon. The whole credit of the work is his. I must take my full share of whatever blame there may be. ‘You should always begin with your second house,’ a lady once wittily said to me. But could this paradox be put into practice the second house would be as much open to criticism as the first. However great your experience may be, you cannot arrive at perfection. I was anxious from the outset to sacrifice every consideration to ensure comfort, and for this reason determined against the introduction of a central hall, which, in my opinion, is fatal to all comfort; or if made into a cosy and liveable apartment, condemns every other sitting-room to complete solitude. But a hall is, nevertheless, an indispensable feature in a country house of any size, and the want of a large room where my friends could all meet, and read and write without disturbing each other, was so much felt, that in 1889 I built one of this kind, which though not in a central position has to some extent at least redeemed the error I had made.

A word may be expected from me concerning the internal decoration of the house. In this M. Destailleur took but a very small part. I purchased carved oak panelling in Paris for several of the rooms, to which it was adapted by various English and French decorators. Most of this panelling came from historic houses; that in the Billiard Room from a chateau of the Montmorencis; that in the Breakfast Room and the Boudoir from the hotel of the Marechal de Richelieu in the street which was named after his uncle the great Cardinal, and which has now been transformed into shops and apartments; the Grey Drawing Room came from the Convent of the Sacre Coeur, formerly the hotel of the Duc de Lauzun, who perished on the guillotine; and the Tower Room from a villa which was sometime the residence of the famous Fermier-General Beaujon, to whom the Elysee also belonged.

The ornamental ceilings are either exact replicas of those of the rooms from which the panelling was taken, or copied from ones still in existence in Paris. The old mantel-pieces I secured from the houses for which they were made; the one in the East Gallery was in a post-office, formerly a residence of the celebrated banker, Samuel Bernhard. The modern mantel-pieces are copied from old models.

I have refrained from going into an elaborate description of the pictures, furniture, and ornaments, which are photographed in this album, as it would be as tiresome reading as a catalogue. But so much I may say: their pedigrees are of unimpeachable authenticity. In my young days I burnt my fingers pretty often and severely, but experience taught me caution, and from the time I seriously entered the lists as a collector, I have only acquired works of art the genuineness of which has been well established.

My grateful thanks are due to those who from first to last assisted me in my undertaking. They, too, may have remembered me kindly. M. Destailleur was entrusted by the Empress Eugenie with the construction of her house and church at Farnborough, and M. Lainé by the King of the Belgians with important works on his estates. These commissions they owed—the former indirectly, the latter directly—to me. Of M. Lainé I have nothing to say but praise. Still, I may be pardoned for mentioning that he only designed the chief outlines of the park; the pleasure grounds and gardens were laid out by my bailiff and gardener according to my notions and under my superintendence; while all the farm buildings, model cottages, and lodges, were built by a local architect, Mr. Taylor, of Bierton.

Waddesdon now has its hotel, its hall and its reading-room, its temperance and benefit societies, and its inhabitants are prosperous and contented. The Metropolitan, now called the Great Central Railway, sets down passengers at a station not a mile from the park gates, and my visitors are spared the tedious drive from Aylesbury, on which I expended many a strong epithet during twenty-two long years. A few more plantations are required to furnish the park, and some hovels should be removed, which obstinate proprietors will not be tempted to part with. Otherwise, save a judicious ‘Keep,’ there is little the hand of man can still do. Time must be relied on to improve the house by colouring the masonry and giving it that rich mellowness of tone which age alone can produce, and beautify the grounds by allowing the trees to grow and expand. A future generation may reap the chief benefit of a work which to me has been a labour of love, though I fear that Waddesdon will share the fate of most properties whose owners have no descendants, and fall into decay. May the day be yet distant when weeds will spread over the gardens, the terraces crumble into dust, the pictures and cabinets cross the Channel or the Atlantic, and the melancholy cry of the night-jar sound from the deserted towers.

Waddesdon Manor was built by Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild between 1874 and 1885 to display his collection of arts and to entertain the fashionable world. Opened to the public in 1959, Waddesdon Manor is managed by the Rothschild Foundation, a family charitable trust, on behalf of the National Trust, who took over ownership in 1957. It’s home to the Rothschild Collections of paintings, sculpture and decorative arts. For more information about Waddesdon Manor click here and to learn more about the Red Book click here

Waddesdon Manor is a partner in the research project Jewish Country Houses—Objects, Networks, People, in collaboration with the University of Oxford and others, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. As part of this initiative, Waddesdon Manor have digitised the writings of Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild held at Waddesdon, making them accessible to the public and offering new perspectives on his life, interests and collecting.