Commonplace

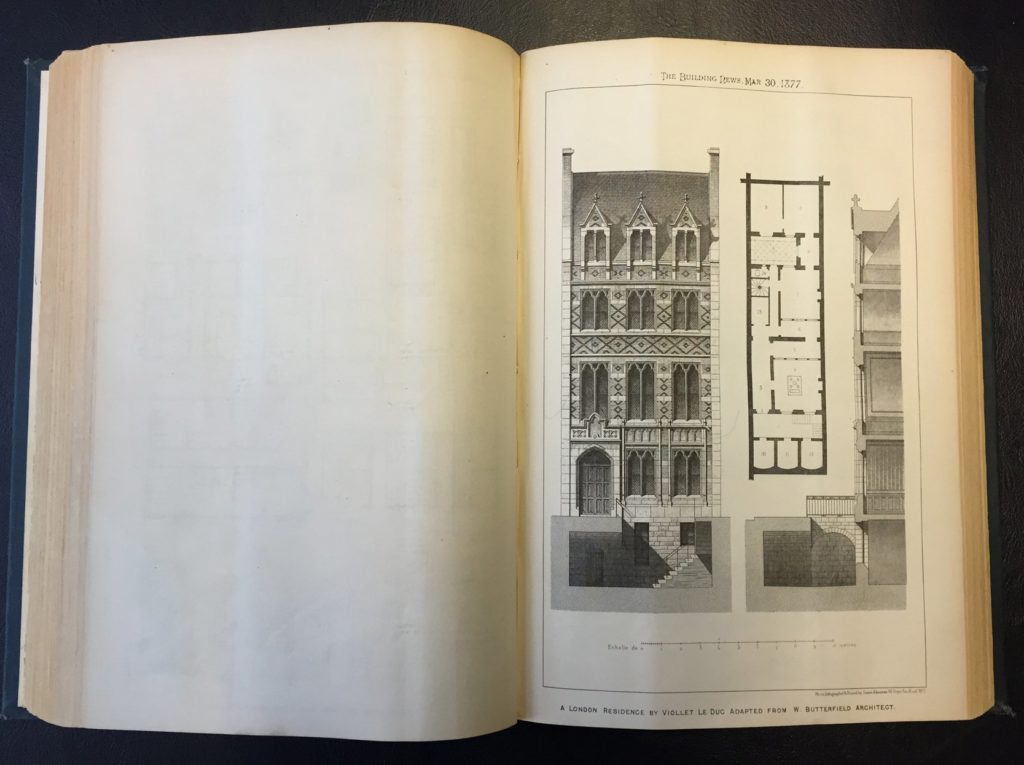

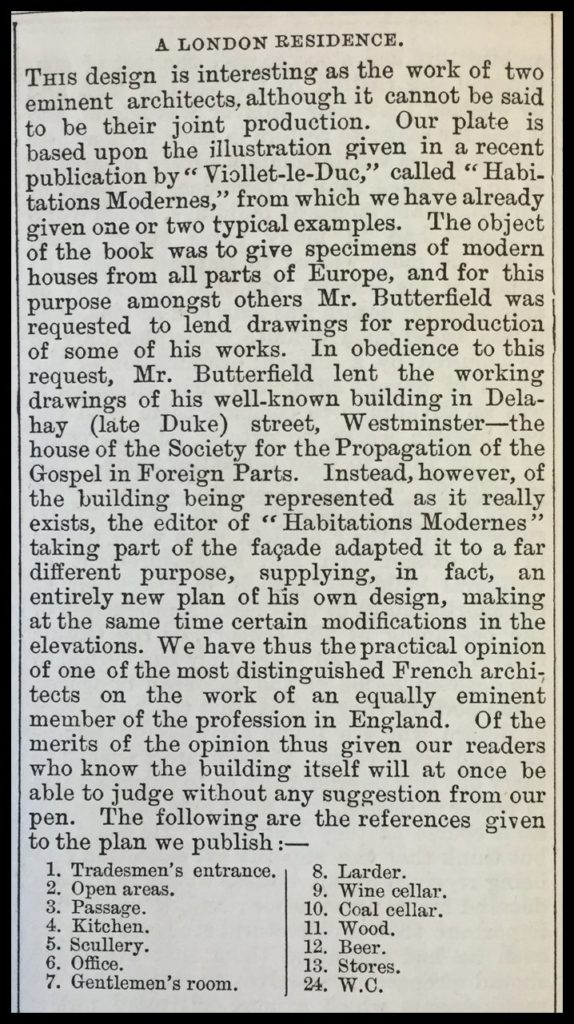

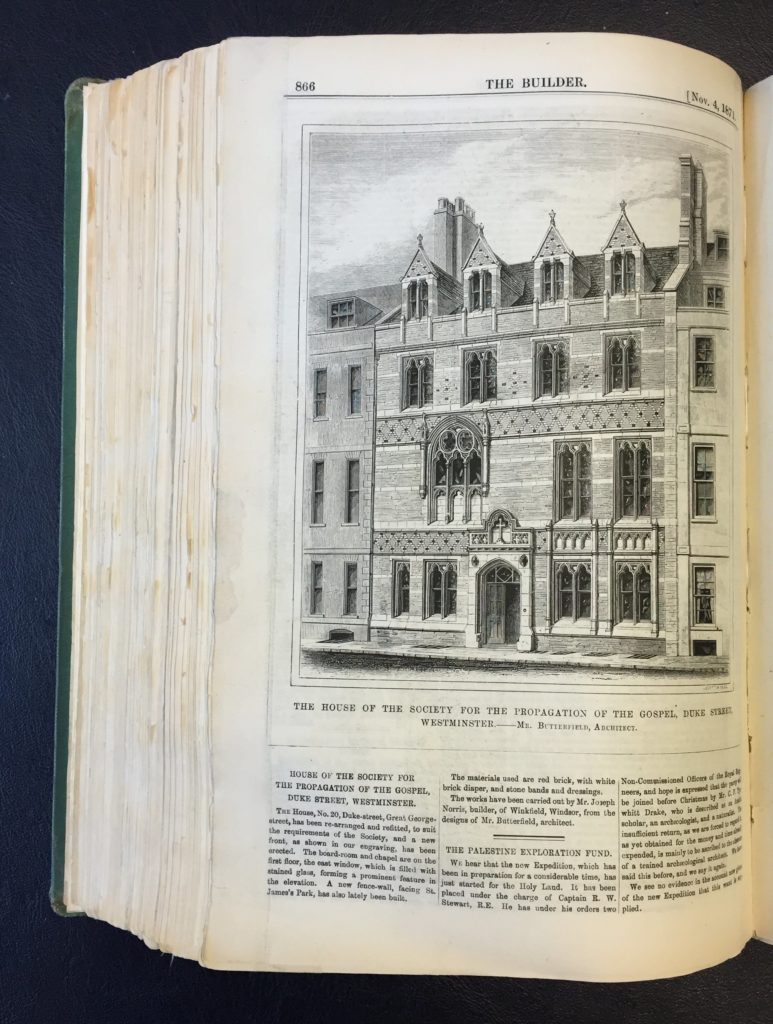

In 1877, London’s Building News reprinted – as the ‘work of two eminent architects, though it cannot be said to be their joint production’ – an elevation, plan, and partial section published by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc as a model town house, noting that this supposed ‘London Residence’ had been adapted – with due if quite deceptive acknowledgement – from a portion of William Butterfield’s offices for the Society for the Propagation of Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) on the basis of drawings kindly lent by Butterfield to the great French polemicist.

The elevation of Butterfield’s SPG building had appeared six years earlier, in the pages of The Builder. This drawing shows the nondescript buildings to either side of SPG, and it is evident that Butterfield was refacing one section of the block and rearranging its interior, but keeping the floor and roof lines of the early nineteenth-century terrace. The London press – unlike Viollet – had then been violently hostile to the built work, finding it brutally vivid and wilfully ‘original’: one critic prayed that ‘time and London smoke will soon tone down the startling look of this work, which is somewhat at present in … the streaky-bacon style….’ Butterfield, growing up above his father’s shop on the Strand, living and working nearly all his life a few doors away in Robert Adam’s own suite in Adelphi, was deeply interested in metropolitan streetscaping, and in the conservation of London’s spatial character. He wrote vehemently in the press to protest the demolitions attendant on the expansion of the Embankment and Trafalgar Square and started the campaign to preserve St Martin in the Fields, which he much admired.

At the same time as the SPG design, Butterfield had actually drawn on it for a set of ‘London residences’ of his own, at 37–38 Bury Street, St James’. These ‘residential chambers of first-class character’, as described by The Architect on 19 November 1870, had an almost identical profile to that of the SPG (which has been long since demolished), but are rendered much more simply, with the end bays beautifully expanded. The 66-foot long frontage, 70 feet in height, was (as it happily remains) ‘in picked stocks, relieved by bands of red bricks, with a sparing introduction of blue Staffordshire headers’. While there are only two entrances to the Bury Street Chambers, the description of the plan suggests that there were four separate units. City directories indicate that they were occupied by professionals in 1879 – serving their purpose as chambers for residence and business. It seems to have been a block of ‘first-class character’ for a while – a ‘gentleman’s servant’ from no. 37 appears in court charged with theft in 1846. Before that it was less grand, but markedly more exciting, since the poet George Crabbe lodged at this address in 1817, and the famous Irish poet and songwriter Tom Moore nearby at no 27. By 1930, the ground floor was occupied – as it has been since – by art galleries.

At about the same time, Butterfield made another row of four model terrace dwellings, in Paddington, just to the west of the new church of St. Michael’s Star Street and its schools, probably at the behest of St. Michael’s leading patron William Gibbs (the great Bristol merchant who funded Butterfield’s chapel at Keble College). Both Gibbs and his friends the Coleridges of Heaths Court lived close by in the grand nouveau-riche enclaves of Tyburnia near Hyde Park that are so mercilessly satirized in Vanity Fair and in Trollope. Gibbs and Coleridge went to the fashionable St John’s Hyde Park church, creating St Michael’s, with its schools and social services, in the 1860s to serve the much humbler and rather riotous district just to the north – a mix of dwellings and commerce of all kinds – often appearing there on Sundays themselves. Butterfield’s terrace – there may be another one adjoining, at larger scale, but this is not proven –seems indicative of the sober tone that such High Church missions were meant to introduce into the more disorderly quarters of London.

In fact, these terraces were so rigorously simplified that most modern eyes, if they notice at all, have been disappointed in their plainness. But Butterfield was as fierce a polemicist on the ground as Viollet was on paper; not least in taking such a different approach between the new front for a public building that must be fussy enough on a nondescript street to announce its purpose and ecclesiastical temper, and a set of dwellings, where he was ruthlessly straightforward, simply making the structure and divisions emphatic – the eyebrows, brick headers and string courses – without breaking the plane, and letting that underlining serve as all the ornament. One can read both domestic ensembles – one for the rarefied atmosphere of St James’ and the other for the bustle of Paddington – as persuasive propositions for a sturdy, well-lit, undemonstrative, rational and subtly expressive domestic landscape, a new ‘commonplace’ that would bring the economies and scale of modern construction and the growing efficiencies of Victorian urban home life into harmony with the everyday characteristics of London’s Georgian street-fronts.