Some Thoughts on Sheds

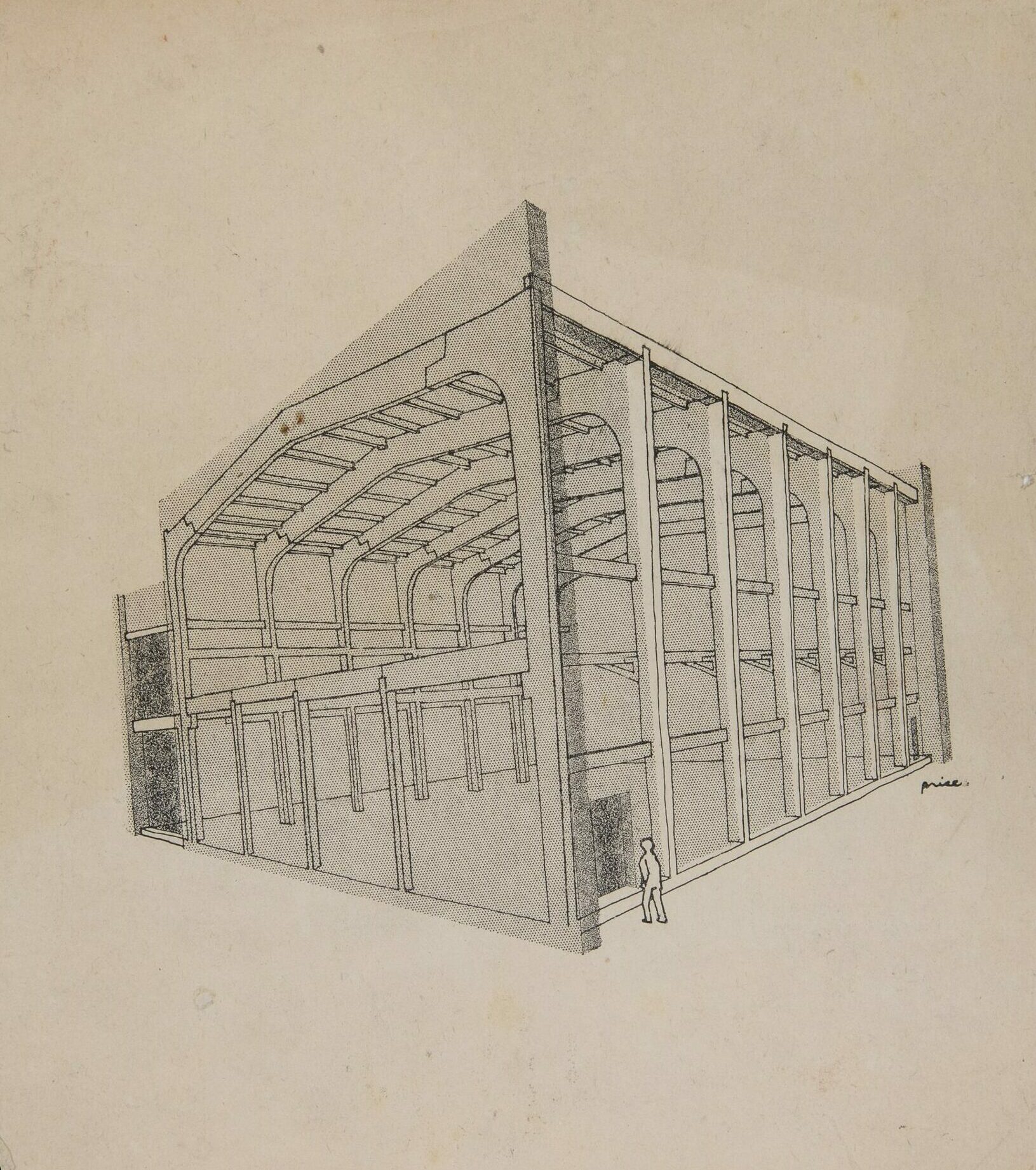

In architectural terms I take ‘shed’ as a neutral word, meaning a structure at any scale open at one or two ends, devoted to storage, display or industrial activity, in which the roof providing shelter is its primary element – in effect a cover with minimum foundations and form: train shed, goods shed, customs shed, wood shed, tool shed, bike shed, aircraft hangar being its most notable expressions and the 19th century railway station and 20th century aircraft hangar its most admired, though my own favourites are the bow-truss sound stages (closed but still on a shed system) of the Hollywood studios. Sheds used to carry a ‘shed roof’ – meaning a canted cover providing an open span with no internal supports, but the curved metal and shaped composition roof of the 1920s onwards also fits. In these terms it is in no way a synonym for any temporary or informal structure, nor for improvisation, nor for the use and reuse of cheaply available materials. But – with the ubiquitous garden shed in mind – this seems to have become the common usage.

Indeed, in cultural terms the word has increasingly come to define the garden shed or the lean-to, no longer conforming to the architectural meaning but now referring to a small, enclosed space without infrastructure – in effect a hut or cabin. In that sense it is not neutral at all: it is the extra-domestic or counter-domestic escape ‘shed’ that in many places – most notably in Australia, where they have manly associations devoted to it – is now part of a huge and disturbing masculinity cult. In English language culture there are a few benign readings in storytelling – like the joyful allotment shed that stars in Mike Leigh’s Another Year – but the domestic or agricultural shed is primarily associated with something sinister and often violently erotically charged, or associated with loneliness, secrecy, hiding, exclusion, psychic disturbance and desperation, for which it serves as a metaphor: ‘put him in the shed’, ‘something in the woodshed’, ‘bury him in the shed’.The slave shed is a particularly important and volatile topic. The forgotten black half of America lived effectively in ‘negro cabins’ or sharecropper cabins, shacks that were little better than the plantation’s animal sheds, until well past Emancipation. Cities were full of them: the built domestic landscape of Los Angeles until the 1940s was studded with sheds and lean-tos (kitchens, toilets and wash-houses), and the campaign for the hygienic modern house was largely designed to get rid of them.

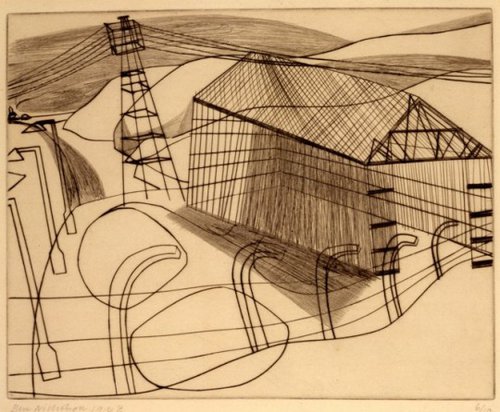

Most of rural and suburban America, built of wooden frames and boards, carries either within its structure or on its surface an echo of the shed; and sheds may be the most important single architectural feature in American art, where it is fraught with meaning – it is a subject in the two most popular ‘national’ paintings (Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World and Grant Wood’s American Gothic); the fisherman’s shed (or ‘shack’ in American usage) at Rockport is known as ‘motif number one’ – for ‘the most often painted subject in American art’; and it goes on forever – Rockwell Kent’s Adirondack scenes, Georgia O’Keefe and Alfred Stieglitz at Lake George, early Clyfford Still on the prairie, and just about every photographer of American landscape.

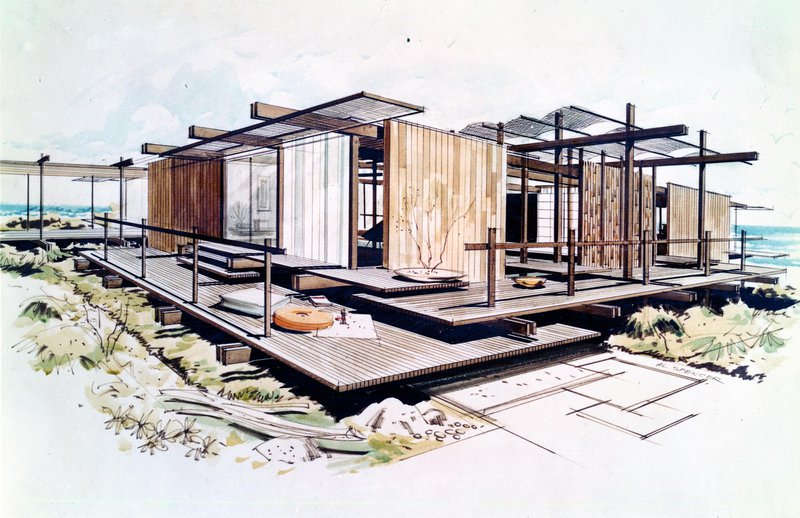

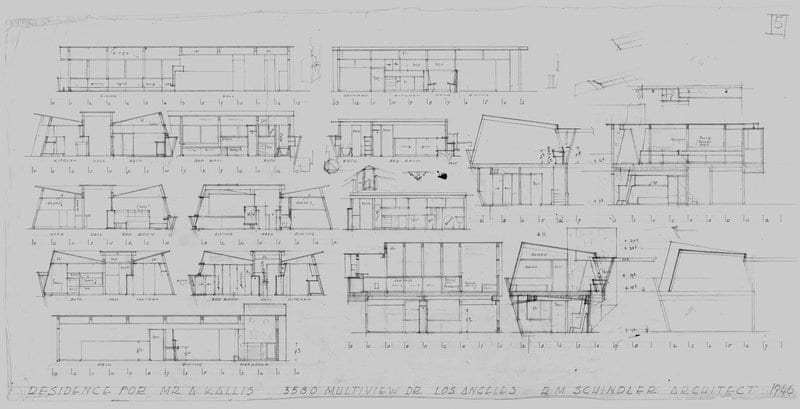

The shed was the principal subject of California scene painting (and indeed a lot of ‘American Scene’ work too) and critically important to California architecture: for great historicists like John Byers in the 20s reminiscing and romancing the Mexican rancho; for Gropius/Wachsmann in their panel system and Cliff May in his prefab ranch-houses of the 50s; for proto-modernists like William Wurster in his pioneering Gregory farmhouse of 1926; and above all for Rudolf Schindler – not just in the famous ‘Schindler Shelters’ of the 1930s but right to the end when Schindler on his afternoon job was assembling his houses from shed materials in the builders’ yards (his morning job was designing them).

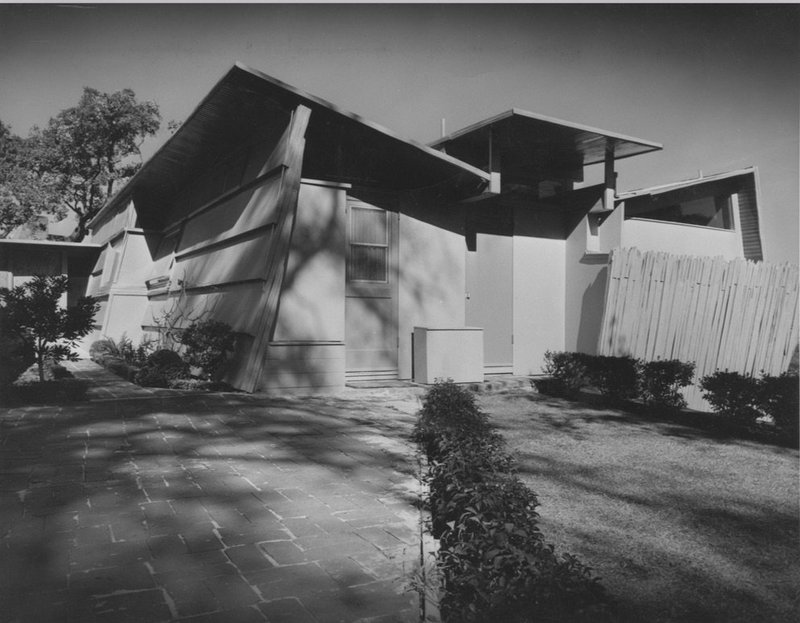

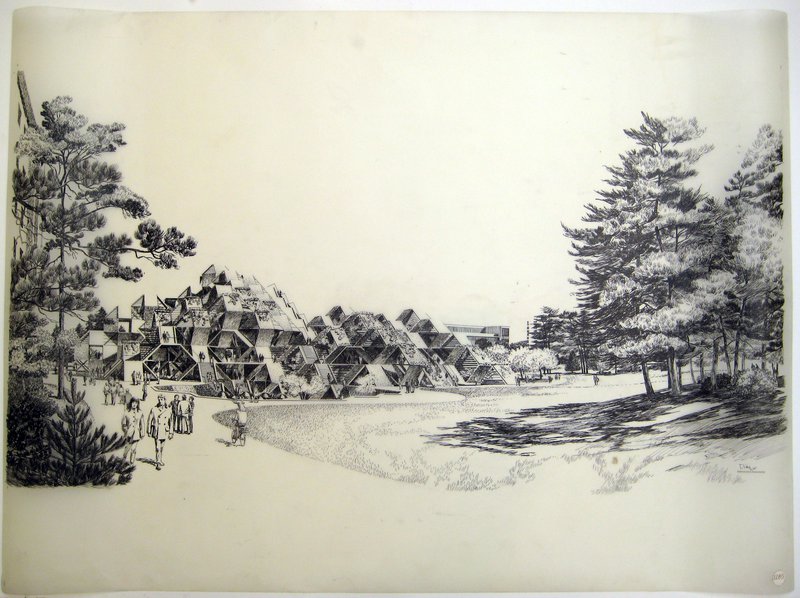

Right through to the radicals of the 60s and 70s when the industrial shed becomes a sort of genetic reference for Frank Gehry, for Thom Mayne and the other members of the Venice Beach confederacy of the early 1970s, and for Moshe Safdie’s concatenation of open sheds in the unbuilt student union for San Francisco.

The rural shed, fraught with sentiment, not only sets a material and constructive vocabulary for Charles Moore at Sea Ranch and his residential college at Santa Cruz, but – once Moore and Venturi had first applied the traditional single canted shed roof to dwelling space – ended up producing an entire suburban landscape of what became known as ‘shed-roof’ townhouses and condominiums, slickly dressed in stucco. Precedent bred precedent, as the near vernacular of LA ‘industrial’ and ‘hi-tech’ in the 80s and after, moved the conversation with industrial sheds too into fashionable everyday housing. Now, hot off the press, Diller, Scofidio, Renfro at the Berkeley Museum marry a gleaming shed of a new type to a converted urban shed of the old, and we all wait to see what Google does for the shed revival in the vast hangars of its new campus.

– Nicholas Olsberg