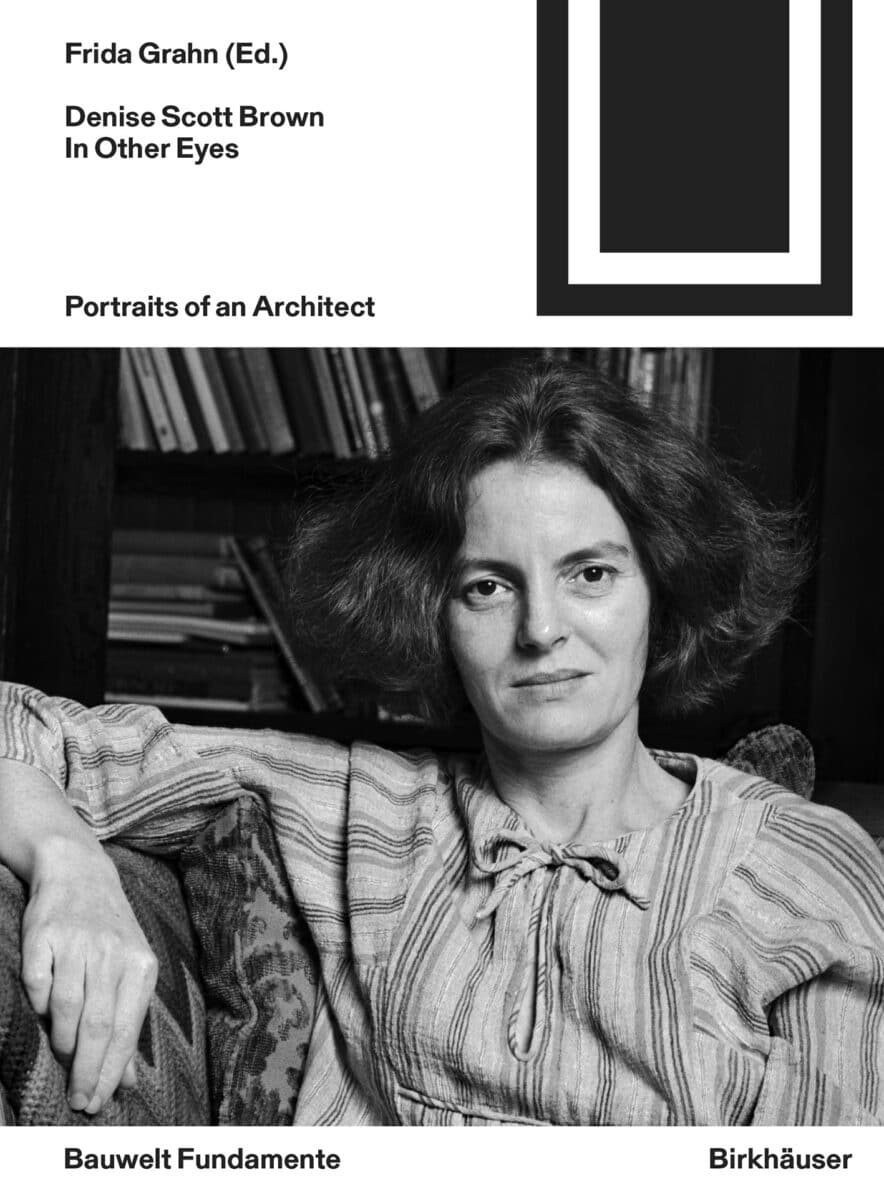

Denise Scott Brown. In Other Eyes: Portraits of an Architect (2022) – Review

Denise Scott Brown In Other Eyes: Portraits of an Architect is a welcome and necessary publication. Its overview of the ideas and career of Denise Scott Brown establishes the rich foundations of her work in education, urban planning, and architecture, as informed by her attentions to the city as it is lived in, used, and experienced. It is also a beautifully curated book, the sensitive work of its editor Frida Grahn who, in her own research trying to assess the reception and impact of Robert Venturi and Scott Brown on Swiss architectural practice, came to focus on Scott Brown’s specific and somewhat obscured contribution.

The award of the Pritzker Prize in 1991 to Venturi alone (although Scott Brown is mentioned in the Jury’s announcement and citation, and deep into Venturi’s acceptance speech) is a notorious example of this studied negligence, which can only be explained by a deeply ingrained misogyny regarding the role of women in joint architectural practices and a notion that the complex work of urban design, in which Scott Brown was exceptionally skilled, was not architecture. The denigration of the authority of women in male-dominated scenes of academia and professional practice is a strong theme throughout this collection of essays and clearly marked their protagonist.

However, this book demonstrates through a series of portraits of Scott Brown, the specific character, originality, and relevance of her contribution from the period of her early development, through her work as an educator bridging the work of architecture and urban planning, and then in her practice with Venturi and Rauch, which finally became Venturi Scott Brown Architects. And it is about time. For too long, her rigorous work, particularly in its reading and sensitivity to prevailing urban conditions and the forces that played upon and shaped them, was seen as a mere surface. It served to extend the thesis Venturi postulated in Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) and the outward appearances of Learning from Las Vegas (1972). This situation also reveals something of the tragic dimension of a creative being always finding herself an outsider in worlds that tend to exclude anyone other than insiders. Being Jewish, being a foreigner who, although English speaking, is other, doubly so, in being a woman.

The book achieves the promise of its title. It portrays Scott Brown through the eyes of others, who speak in a chorus of voices. In doing so, it is varyingly objective and personal and frequently moving, particularly in the portraits made by those who have worked with her, been taught by her, or know her. The book opens up for its readers the very significant contribution made by Scott Brown not only to the architectural practice of Venturi Scott Brown Architects (VSBA), but to architectural education and the practice of urban design. Scott Brown’s omission from the Pritzker Prize awarded to Venturi remains an anomaly and an injustice especially when confronted with the substance and invention of her contribution, without which, the work of VSBA would have been profoundly diminished. The voices gathered here so gracefully by Grahn are involved not only in creating portraits of Scott Brown, but also sing odes to her work in education, urban design, and architecture.

The book is divided into three chronological sections that correspond to major shifts in Scott Brown’s life, career, and foci of attention. They include essays by those who knew her early in her career, those who have accompanied and analysed her work throughout its transitions and developments, and those who have been affected by its significance anew. These distinct kinds of voices, or ears, speaking of and listening to the lives of Scott Brown’s work, lend the book both vitality and intimacy. They evoke the memory, appreciation, and excitement of a first encounter.

This sense of the personal, of the work and agency of individuals, of real people—Scott Brown herself, her colleagues, her collaborators, her clients, and those who have encountered and attended to her work, is palpable. The book’s design, consistent with that of the entire Bauwelt Fundamente series published by Birkhäuser, to which it belongs, enhances a sense of intimacy for the reader, who holds a life and a set of episodes and encounters in their hand. The communiative way that the different voices have been gathered together, and the relationships between them, is the editor’s great achievement.

The first section, ‘1950s: Learning’, concerns Scott Brown’s beginnings. It examines her upbringing in Rhodesia and South Africa and her experiences and studies in Johannesburg, when the reader meets the people she met and worked with, including Robin Middleton and her first husband Robert Scott Brown. Themes such as the formation of her receptivity to the idiosyncratic expressions of local popular culture, her ‘African view’ on African Pop that would help her later read both Main Street and the Strip; her exposure to international practices in architecture and urbanism alongside Robert Scott Brown in London and Venice, are explored. These years, which included a period of study at the Architectural Association and contact with British architectural culture and its figures, a return to South Africa and a deeper understanding of its specificities, an international design workshop in Venice, and time in Giuseppe Vaccaro’s office, all served to establish foundations, relations, and ambitions that would mark her entire career.

Her ‘education’ unfolded in a functionalist milieu, through contact with CIAM figures in Venice, and later, Team Ten figures in London, that reinforced both analytical and critical tendencies, particularly in relation to the ‘as found’. What is striking about this period is Scott Brown’s evident sensitivity to the natural and constructed environment, her readings of popular expression and urban conditions in South Africa, shared with her colleagues at the University of Witwatersrand including her contact and relations with many very special people; her ongoing education and contact with architectural culture internationally; and the setting of major concerns that would both guide and give urgency to her work in the future. Reading this section as an accumulation of episodes reveals a fascinating life in architecture. It is palpably human, and the character of the various portraits—an essential aspect of the book with effects well beyond its subtitle—is very affecting. The reader becomes the witness of a mind and its project. The contextualisation of these episodes in essays by others situates Scott Brown’s experiences within the preeminent tendencies in contemporary architectural thought, and among new thinkers who would have profound influences in the development of architectural culture.

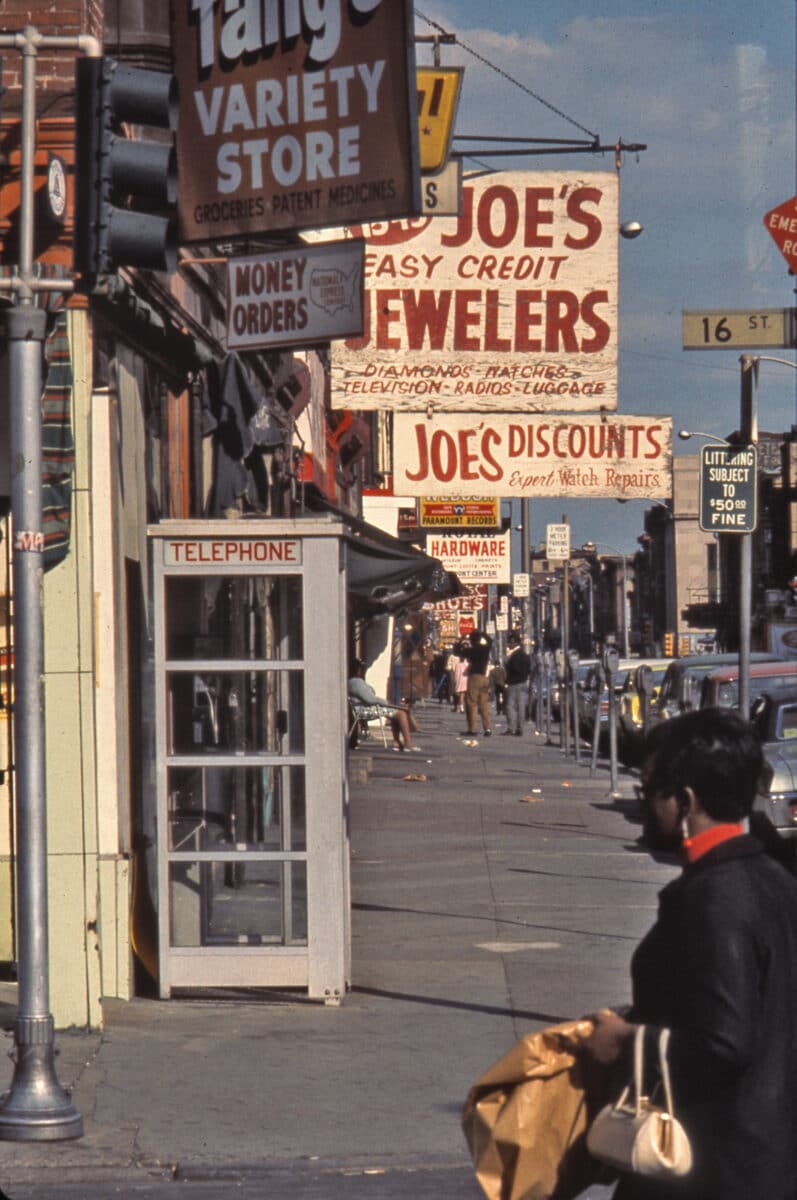

The second section, ‘1960s: Teaching’, is focused on Scott Brown’s work in education. She taught both urban design and architecture in her course ‘Determinants of Urban Form’ at the University of Pennsylvania from 1960 to 1964, at UCLA in Los Angeles from 1965 to 1966, and then to Yale. This is a rich chronicle of a period of pedagogical and methodological invention, of the building of foundations of a practice in urban planning, and of struggle against male-dominated academic environments. Through the testaments and analyses, it is possible to follow the refinement of Scott Brown’s attention on the city as it is, her approaches, methods, and attentions to those who live in it and how they live in it, especially in the face of the violence of urban renewal projects. The essays’ authors attest to her working methods, the forging of her position through her capacity for listening and ‘city-watching’, and her creation of a pedagogy at odds with the projective nature of both urban planning and architecture. Her educational practice is by nature interdisciplinary, crossing the concerns of urbanism, social studies, and architecture, and required collaboration and collegiality. Using methods of field work taken from the social sciences—documenting, speaking to people—requires observation and analysis of the economic, social, cultural, and political ‘forces’, as Scott Brown calls them, that affect and distort urban conditions and impose themselves upon the city and its citizens. Particular attention is paid to the so-called ‘urban renewal’ of large-scale expropriation, demolitions, and demographic change. In the face of this, a variety of tools are used to structure her students’ work so that they may come to know, in profoundly real ways, what (and who) the city is.

The essays highlight the kinds of relations Scott Brown established to pursue this work; and the profound value and the difficulty attached to it, especially as a woman working within academic (and professional) environments dominated by men in which one’s validity, and the nature of one’s visibility and agency, were unnecessarily and perpetually an issue. At UCLA, for example, she was constantly subject to misogynistic policy and pressure and Sylvia Lavin’s essay, ‘Positioning Denise Scott Brown: Los Angeles, 1965-1966’, touches on the various margins she occupied as Jewish, ‘foreign’, woman. An especially egregious example was her inability to publish what was effectively her thesis, ‘Form, Forces and Function in Santa Monica’, due to lack of institutional support and funding, while Venturi’s contemporaneous manuscript received the full support of the Graham Foundation and the Museum of Modern Art.

A positive spin might have it that her ‘outsider’ status also permitted her to work around conventions. The interdisciplinarity of her approach to urban planning is an example of this, as was her ability to look at Los Angeles and its environs in ways that could recognise the forces that formed it. This skill was learned from her experience of urban conditions in Johannesburg, her ‘stage’ in Rome, and her time in contact with the British post-war architectural scene, with its special political dimension. There is so much here: Scott Brown’s work on South Street, Philadelphia; the epochal studies of Las Vegas’s Strip in Yale’s design studio she initiated and then conducted with Venturi and Izenour; its means and mechanics of communication; the vehicles (literally, automobiles) used look at it and its privately-owned public spaces, immortalised in Learning from Las Vegas (1972); and her acute sensitivity to camp and her ‘African View’ of Pop. There is a special atmosphere to this section, which is alive on the page. This feeling was especially evident throughout a day-long symposium concerning the book at Yale University (8 February 2023). This featured many of the book’s contributors, and the atmosphere could be best described as something like an academic, professional, and sisterly solidarity, affection, and love for Scott Brown.

The third section, ‘1970-2020: Design’ follows the time between Scott Brown’s studies and her joining the architectural practice of Venturi and Rauch, which at first she manages before becoming a full partner. Her work in planning becomes essential to the practice as a whole, not only in terms of the projects that become its bedrock, but the influence of social sciences in its ongoing thesis, from the methods of its work in urban planning to its exhibitions, notably Signs of Life: Symbols in the American City (1976), and publications. Impossible to describe in all its aspects, this section also concerns the reception of Venturi and Scott Brown in Europe, or at least by European protagonists of Modernism, with telling reflections by Stanislaus von Moos, Jacques Herzog. There was something that could not stick; their work could not be dismissed, and furthermore, it was bound to concerns for the city and its future that were appealing for that generation of architects that would emerge not only post-CIAM, but post-Team Ten.

An essay by Grahn herself is concerned with Venturi and Scott Brown’s invitation from Pierre Bechler to speak in 1978 at a symposium on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of CIAM’s first conference at La Sarraz, Switzerland. They were invited to speak due to their new ideas about communication in architecture. Both partners gave talks, with Scott Brown speaking about their urban projects, community participation, and small interventions. Grahn cites Scott Brown’s inverting riposte to Daniel Burnham’s pronouncement: ‘make little plans’. The enthusiasm of the young audience is recorded alongside the subdued and chauvinistic treatment of Scott Brown as the wife of the architect.

The essay by von Moos returns to lessons learnt from Venice and the CIAM Summer School, 1956, which Scott Brown and her husband Robert Scott Brown (who died in a car accident in 1959) took part in. It looks at how readings of the city, its form, its accommodation of daily life and the representations embedded in the very stones of Venice played a role almost continuously in the unfolding of Scott Brown’s academic practice and the professional practice she shared with Venturi until his death in 2018. The section ends with an analysis of Scott Brown’s working methodology as it unfolded in and informed the Venturi and Scott Brown’s design of the Capitol of the Département de Haute-Garonne in Toulouse (1999), a building that responds to the forces at play in the town in which it is embedded, through lessons drawn from the town and its ‘desires’.

The book concludes with an epilogue, in the form of email letters from Scott Brown to Biljana Arandelovic and Grahn. These are both personal and charming descriptions of a life; a life’s work and life with Bob. It is difficult not to become emotional at their openness. The book finally bids adieu with photographs made by Scott Brown in South Africa, Venice, and Las Vegas. Although some were taken up to 70 years ago, all have the wide-eyed vitality and hopefulness of footage of the Beatles writing songs for ‘Let It Be’.

Frida Grahn, ed. Denise Scott Brown. In Other Eyes: Portraits of an Architect (2022) is published by Birkhäuser. Copies of the book can be purchased here.

Mark Pimlott is an artist and assistant professor of architectural design/interiors at TU Delft.

Personal Note

The work of Scott Brown and Venturi has had an influence on my attentions to architecture from the beginnings of my studies at the end of the 1970s until the present.

Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966) was the second architecture book I ever acquired (following Michelle Stone and Allison Sky’s Unbuilt America (1976) that featured Venturi and Rauch’s ‘Bill-ding Board’). The first guest of a lecture series I coordinated at McGill University’s School of Architecture was Steven Izenour, who showed us lantern (or large plate) slides of Main Street and Las Vegas and their exhibition Signs of Life (1976). My fellow university colleagues—staff and students alike—were all troubled, one way or another, by the ‘post-modern’, particularly as it landed in an educational environment dominated by Bauhaus principles and open-frame geometrical structures in the design studios, and Auguste Perret’s concrete rationalism in the history course led by Peter Collins.

Our attraction to the architecture and corresponding regard of the city exemplified by Venturi and Scott Brown on one hand and Aldo Rossi on the other were considered dangerous; and as students, we regarded any architects that could simultaneously address mannerism and Main Street as beguiling. Later, as I followed the work of Venturi Scott Brown with either surprise or bemusement, their proposals bewitching (such as the small, perfect beach houses), or simply too much: the floral phase of façades perhaps being the least digestible; these were quite often disputes with the language of surfaces.

But then, other events would remind me of the power of the architects’ arguments. For example, the arguments embodied in their 1987 RIBA lecture on their design for the National Gallery extension in London (the Sainsbury Wing) were compelling. These included the suggestion that Wilkins’s weak façade to Trafalgar Square was best experienced obliquely (made almost obligatory by the arrangement of roads around the square at the time), and that this consideration rendered their compressed composition of pilasters and half-engaged columns a necessary conclusion to Wilkins’s attenuated design. They also proposed different logical systems determining and distorting the plans of the ground floor and piano nobile, that reflected the competing forces, from desire lines to notions of perspective composition, at play. This lecture was largely greeted as an exercise in aesthetics, however, consistent with the speech given later by Venturi at the Pritzker Prize award ceremony in 1991.

In 2001, I had the pleasure of sharing a stage with Izenour in Washington DC. Using his lantern transparencies of Main Street and the Strip, he brought to some classic Venturi Scott Brown projects the life and intelligence of the Las Vegas Studio and the publication Learning from Las Vegas (1972) back to the surface. This surface concealed, under its gaudy exterior, a rich and substantial—and specifically American—interior: a portrait, a document, an analysis, an inquiry, a true piece of research, a revelation.

One way of knowing Venturi is through the modest manifesto of Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, with its pairing of a theoretical and conjectural text on architectural expression and composition with examples of early works of the practice of Venturi and Rauch. This is but one aspect of more complex movements lying beneath the almost parallel work in Las Vegas. This seems, in its embrace of a specific total environment and its thorough analysis, to have been asking the perhaps never before asked questions—what is it? and how does it work?—in order to come to terms with the world as it is made. This was a messy, vital and compromised but much deeper practice. The work on Las Vegas, which emerges from the special studio run by Scott Brown, Venturi and Izenour for Yale University in 1968, was the outcome of studies Scott Brown had begun while teaching at the University of California in 1965. There, the structures she created for the analysis of urbanised conditions bound the consideration of architecture with methods drawn from the social sciences, and inquiry into the conditions and desires of those who lived within them and who were affected by policy and speculation formed the core of her work.

Scott Brown’s methods, which would be refined over the years to become a substantial urban design practice within the firm of VSBA, gave additional structure to that practice, and deeper foundations to architecture that could occasionally be dismissed as mannered or superficial. Of course, both of these terms would likely be welcomed by the architects, embraced not as pejoratives, but as legitimate aspects of their work.

In 2005, Venturi and Scott Brown visited TU Delft to give lectures apparently dedicated to communication and coinciding with the publication of VSBA’s book Architecture as Signs and Systems for a Mannerist Time (2004). The event was dominated, at least in my memory of the event, by Scott Brown’s lecture on urban planning and design. This included the practice’s work on projects such as the Strip in Las Vegas, South Street, Philadelphia, the National Gallery, and a variety of university campuses in the USA and China (Penn, University of Michigan, Tsinghua University). Here, the notion of ‘forces’ germane to local conditions and desired uses were demonstrated to be influencing factors in determination of the plan. The object of campus planning was to enhance the utility and pleasure of existing resources, and create spaces where people would want to be, and so meet and exchange ideas. This was, in Scott Brown’s words, the ‘90% of their practice, land-use and infrastructure planning that runs through their buildings’. I thought, at the time, that this work gave substance to all the work of the practice; and that outward appearances were somehow reflections of the forces acknowledged and grasped in the large- and micro-scale urban studies forming the bases of their plans.