Frank Lloyd Wright, House for Edith Carlson, 1939, Part I

This is part one of the true story of librarian Edith Carlson, who in 1938 commissioned a house from Frank Lloyd Wright. The letters that document the project are now in the Drawing Matter collection.

Extracted from Stories from Architecture: Behind the Lines at Drawing Matter by Philippa Lewis, published by MIT Press © 2021. Order the book here. Some of the texts were first published as ‘Behind the Lines’.

My dear Miss Carlson: we’ll see what can be done –

Sincerely,

Frank Lloyd Wright

June 14th, 1939

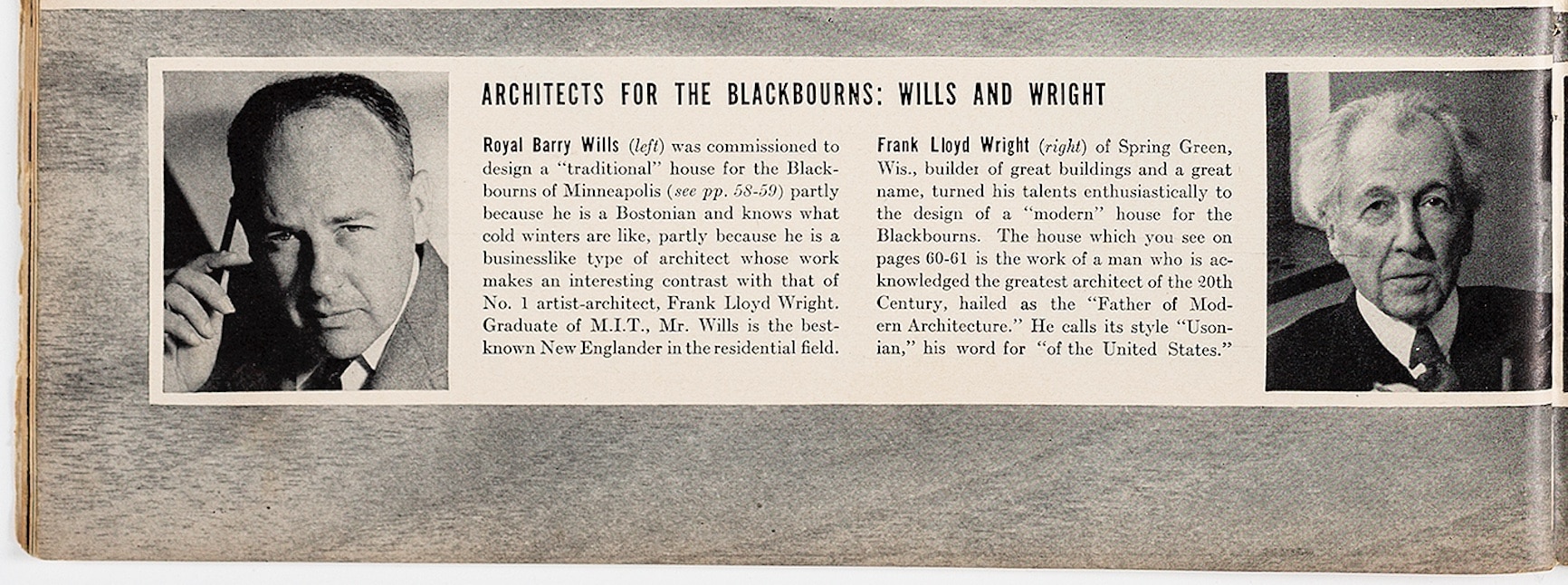

Written on cream paper printed in red with two addresses – Taliesin Spring, Wisconsin, and Paradise Valley, Phoenix, Arizona – this was the only letter that Edith Carlson received from the man described in her copy of Life magazine as ‘the greatest architect of the twentieth century.’

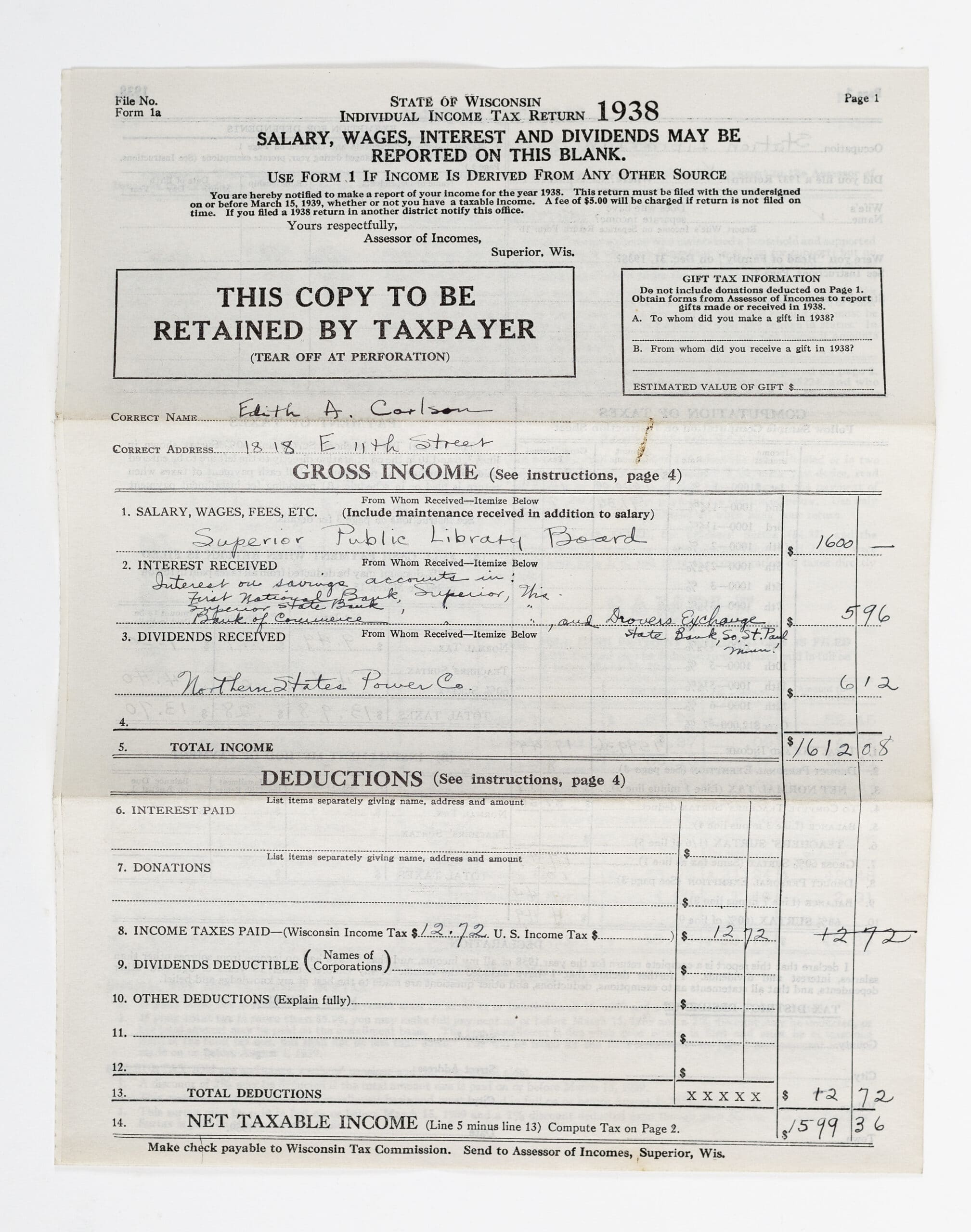

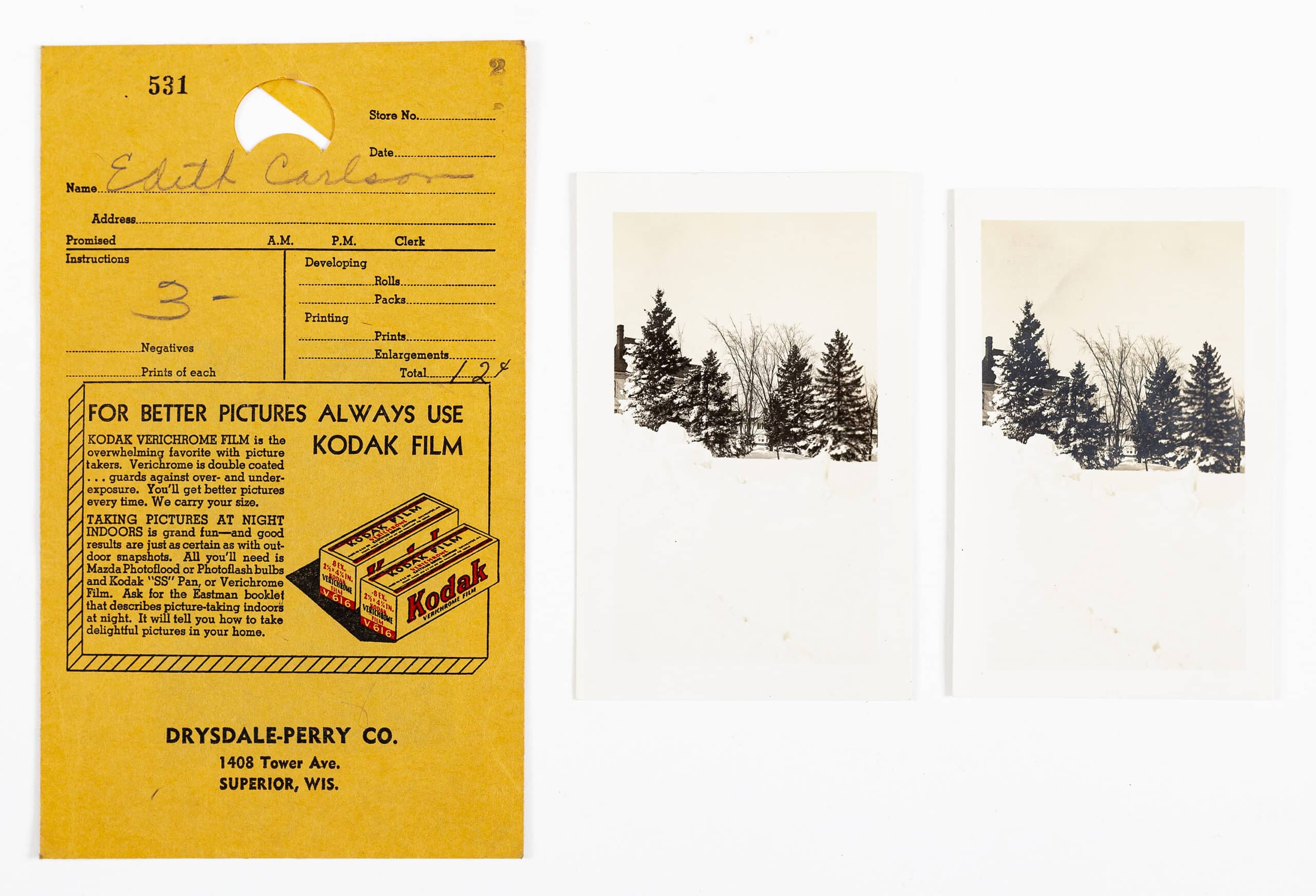

Edith lived in Superior, Wisconsin, where winter can be 35 degrees below zero and frost penetrates to six feet. In 1938 she described herself and her project on a Personal Data sheet sent to Frank Lloyd Wright’s office.

Edith A. Carlson, 1818 E 11th Street, Superior, Wisconsin 39 and single, with no dependents, at present

Work: Librarian

Present Position: Station Librarian, Superior Public Library I am living at home now, but I have no room of my own and no place to keep my belongings. They are here and there. I sleep in the living room and read there, too, when I can.

Present Annual Salary: $1,600

Personal Insurance: $1,000; 40-year endowment with Central Life Insurance Co.

Annuity policy with Metropolitan Insurance Co. Accident policy

Sickness reserve $100 Debts: None

Money in bank now for house: $700. I should have $300 more by August 1939. I do not want to build before that time. I am planning to apply for a loan from the State Building and Loan Association, Superior, for the remainder.

She wanted:

Simple, comfortable shelter for three adults, for my mother and me on the first floor, and for a roomer on the second floor, with a maximum of privacy for each. Maximum cost to be $5,500 for house, including furnishings, grounds, architect’s fee, etc., but not including the lot.

As a librarian Edith had the inclination and the resources to research a subject thoroughly. Frank Lloyd Wright inspired her and she had no compunction in writing a peremptory letter to the owners of another Wright residence, the Jacobs family, whose house ‘Westmoreland’ was in Madison. Edith addressed the letter to Mrs. Jacobs but it was duly returned with the answers written in thick pencil by her husband Herbert.

August 20th, 1938

My dear Mrs. Jacobs,

Will you please answer a few questions about the house that FLW planned for you and your family? I read about it recently in Architectural Forum for January 1938 and would very much like to know what you think of your house after living in it almost a year.

Do you like your house?

Do you feeel at home in it?

Do Mr. Jacobs and your daughter like it?

Do you find your house comfortable and convenient?

Is it easy to keep clean?Emphatically yes.

Is it winter air-conditioned?

No.

Are the heating and lighting systems adequate? Are they economical to operate?

Yes.

Are the carport, glass doors, and cement floors satisfactory in winter as well as in summer?

Yes.

Is there anything about your house that you do not like?

No.Is $5,500 all that it cost you?

Yes.

Have any photographs of the interior been taken?

None satisfactory.

Edith Carlson must have read with attention the article on the Jacobs house in Architectural Forum. But maybe she skimmed over the sentence, ‘The house of moderate cost is not only America’s major architectural problem, but it is the problem most difficult for her major architects,’ and instead fixed on the one that followed: ‘As for me, I would rather solve it with satisfaction to myself… than build anything else I can think of.’

In later years, long after her dream of living in a house designed by the great man had finally been extinguished, Edith might have picked up that first single-line note from Wright – ‘We’ll see what can be done’ – and retorted ‘But nothing was done.’ Pragmatism had been defeated by idealism.

It had all started with such optimism. The town of Superior would have an architectural gem, and she would have the house that met her specifications in every detail. In September 1938 Wright’s secretary, Eugene Masselink, had written positively:

Dear Miss Carlson,

Mr. Wright would be glad to build you a house in Superior and believes one could be built for $5,500.00. The size of your lot is adequate. One need not have an acre of land but the more ground the better.

A great moment. She had already made notes from Modern Architecture magazine and knew that Frank Lloyd Wright believed that modern architecture

1. Is clean

2. Is honest

3. Is functional

4. Is organic

5. Is beautiful

But Edith’s attempts to engage directly with her architect were met with a trail of evasive replies from Masselink.

January 14th, 1939

Dear Miss Carlson,

Mr. Wright has your letter containing the information about your lot and your requirements. He will be able to go ahead with the plans for your house. He would be very happy to see you to discuss the plans with you personally but unfortunately he is in Arizona with his winter camp until spring…

February 2nd, 1939

Dear Miss Carlson,

Mr. Wright has your letter of the 25th. He will keep in mind what you say when designing your house.

However, spring did not bring the green shoots Edith was hoping for.

April 29th, 1939

My dear Miss Carlson,

Mr. Wright left for England before your letter came. He is lecturing there from May 2nd to May 11th at the Royal Institute of British Architects, having been given the Sir George Watson Chair of Literature for this year.

July 11th, 1939

Dear Miss Carlson,

Mr. Wright finds it impossible to break away from his work here in Taliesin to come up to Superior and he hopes you can manage to make a trip down here to Taliesin to go over your house plans with him thoroughly. Can’t you do this soon? Any time will be convenient – just let us know in advance when you will come.

Leafing through her notes she came across a quote by one Albert W. Atwood that she had copied out from Barron’s financial paper in January 1939. It now seemed upsettingly prescient:

There are millions of persons who should not own their own homes—the very young, rich or poor, unmarried of any age, childless couples, the widowed, and the elderly.

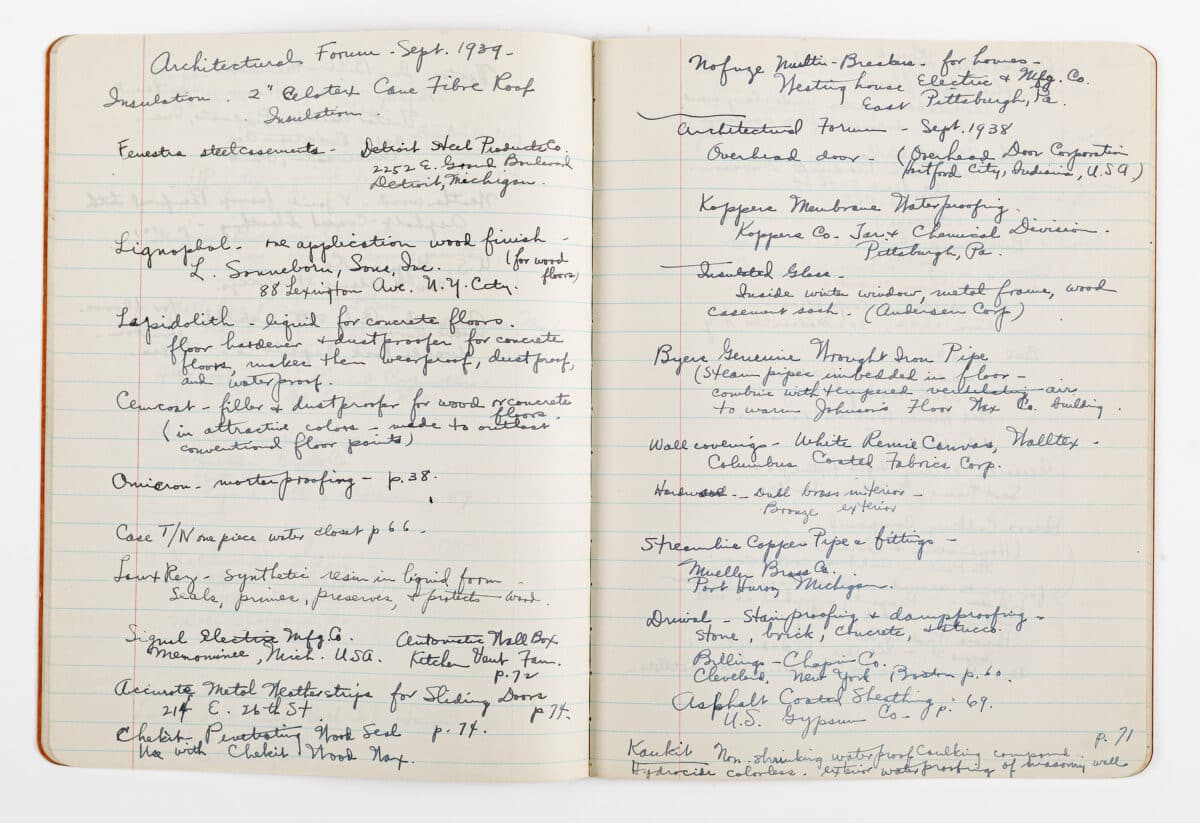

Such cheek. Or was it? The preliminary sketches had arrived mid-April 1939. By return post she sent a check for $165, the three per cent due on their completion. But once she had seen the drawings her mind was naturally crowded with questions. Planning, dreaming, and researching her house had taken up almost all her waking thoughts. She had sheaves of notes: ideas jotted down in the middle of the night, corrections, references to relevant articles on every aspect of the house interiors and exterior.

Her list of suitable building products was lengthy: Bondex Waterproof Paint, Anaconda Copper Tubes, Victor In-Bilt Ventilators, Sta-Lite Board, Prometheus Bathroom Heaters, Lucke Leak-Proof Bath Tubs, Nofuze Multi-Breakers, Flinkkote Mastic, Armicron Mortar Proofing, Lapidolith Liquid for Concrete Floors, Drival Damp-proofing. And naturally for a person who had studied botany at university, lists of plants for the garden (hepatica, trillium, clintonia, scilla).

She looked over her draft of a letter sent to Masselink in the fall of 1939, more than a year after her first letter from him.

I bought my Lot two years ago, wrote to Mr. Wright to find out if he were interested over a year ago, and goodness knows when my house will be built. I don’t.

She thought she had explained everything when she finally traveled to Taliesin in August. What a waste of time that had been. The drawings subsequently arrived, but as she had explained to Edgar Tafel, the architect from Wright’s office assigned to her project (here was the carbon, December 26th, 1939):

I looked first for the windows which Mr. Wright told me he would put in the southeast wall of my house. I could not find any! And I am not building a house without windows on the southeast!! (The first exclamation mark I used to register disappointment; the second to indicate emphasis.) My house must make sense to me and a house in Superior without windows in the southeast is silly.

Was she losing faith? Did she actually write and say ‘It is no longer Mr. Wright’s ‘Below Zero,’ it is my ‘High Spruces.’’ Or had she just scribbled it on her draft letter? A much better name. She had disagreed with his siting of the house precisely because of them:

The house cannot be placed where you have placed it unless I have the lower branches cut off the two Spruce trees nearest the sidewalk, and I can’t do that. I would never feel comfortable in the house if I mutilated those two trees.

She had anyway felt there was perhaps a hint of mockery in ‘Below Zero,’ since she had made her anxiety about the efficiency and cost of Mr. Wright’s underfloor heating patently clear on numerous occasions. She could not afford to be experimental, Mr. Wright must realise that.

If you will refer back to the statement of my financial conditions you will see why it is so necessary that I get a house that works from the very first… a leaking roof, an excessive fuel bill, fireplaces that let in rain and snow, cracked floors are simply not compatible with a librarian’s small salary.

She had written again – several times – to Mr. and Mrs. Jacobs, asking about the heating in their house. Only recently Mr. Jacobs had admitted to having spent money on a new heating plant. ‘And don’t get discouraged,’ he had written as a postscript, ‘It’s worth all the trouble, once you’re in. Occasional reminders of your existence help to jog Mr. Wright into action, we found.’ Well, she’d certainly sent those. Edith remembered how exasperated she had felt on receiving a letter from Edgar Tafel written in December 1939. She could not comprehend why decisions could not be final.

To be continued…