Glarner Wirtschaftsarchiv

Through an unprepossessing door tucked into the corner of two buildings located at the edge of a precinct both rural and industrial is the entrance to the kind of magic world that archives often hide. Founded 20 years ago by Dr. Sybill Kindlimann of the influential local family, Blumer, the archive began as a record of the history of her family’s textile printing factory, F. Blumer & Cie (1828-1980), sited in the factory buildings made obsolete when the firm closed. The documents on paper that Kindlimann started with, record and account books, travel diaries and journals, were soon augmented by the purchase of her brother’s assortment of physical artefacts for stamping, printing, and designing patterns for printed textiles.

Aided by 20 years of weekend voluntary work by Ursula Stocksa alongside a small group of volunteers, archivists, and other specialists, Kindlimann’s Wirschaftsarchiv has grown to embrace 21 separate collections kept in the most immaculate archival conditions. Together, these archives represent the principal industries situated along the river Linth and its tributaries, in whose valley lie the settlements of the Swiss Canton of Glarus. Principally related to the processes of textile production in various forms, these also include the 20th century archive of Therma, a factory for electrical heating devices designed for the home but also for communal and transport kitchens. This was founded by Samuel Blumer in the same industrial area, the Mühleareal (mill district) of the village of Schwanden, in which the archives are housed.

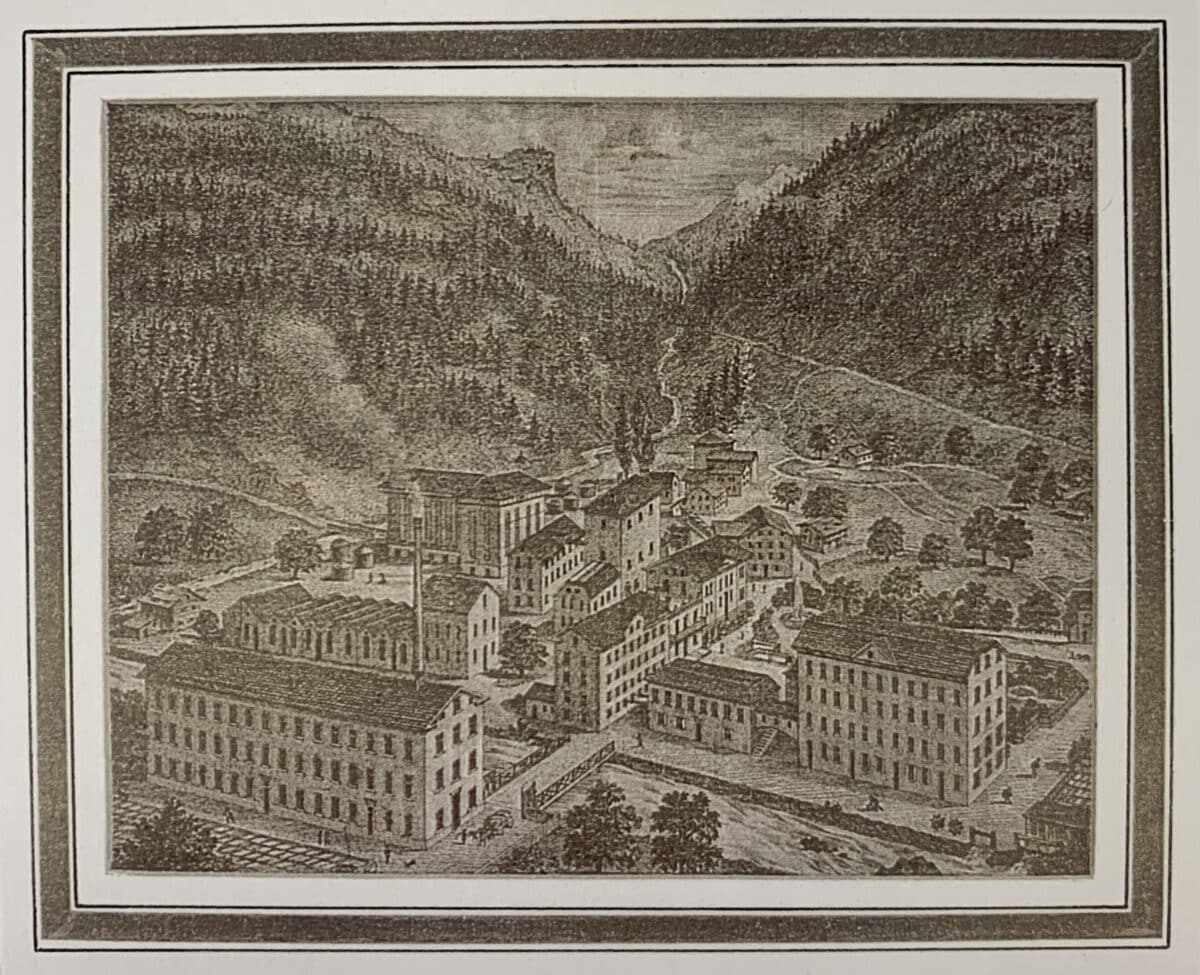

During the 19th century, the factories developed as ensembles that incorporated the various and mostly secret, processes of dyeing and printing textiles in individual buildings. One of the most characteristic of these building types is the Hängiturm, a shed designed for the drying of printed fabric both inside and hanging from external projecting eaves. These factory groupings often (but not always) included the home of the owner and some of the workers within their precincts or immediate hinterlands. Architectural plans for some of these structures are kept in the archives, but the large part of the collection is devoted to the global processes of cultural exchange, interpretation, and dissemination that was the principal business of these family-run companies.

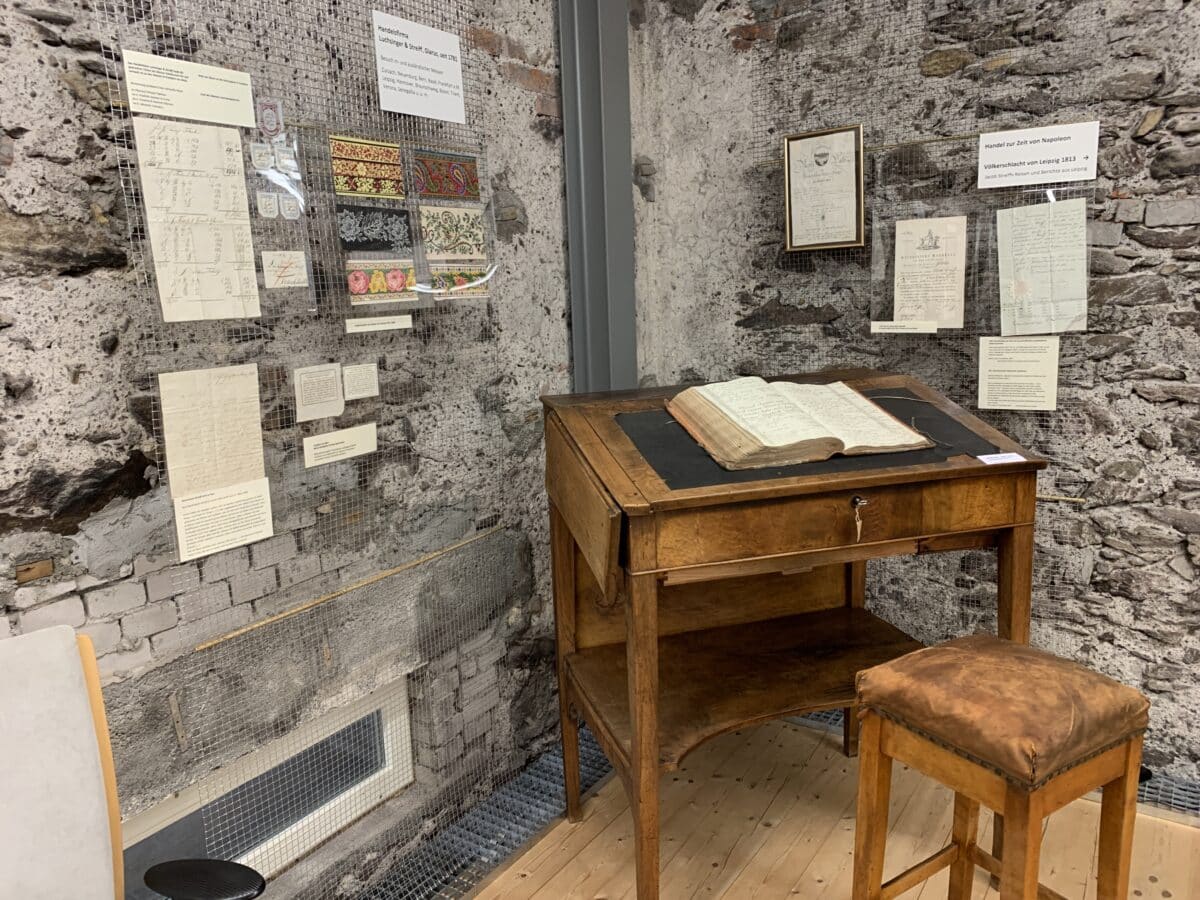

The history of the Blumer family within the larger story of textile production and design in Glarus is presented in a small, two-room museum. Launched in the summer of 2013, it is open to the public for three hours a month.

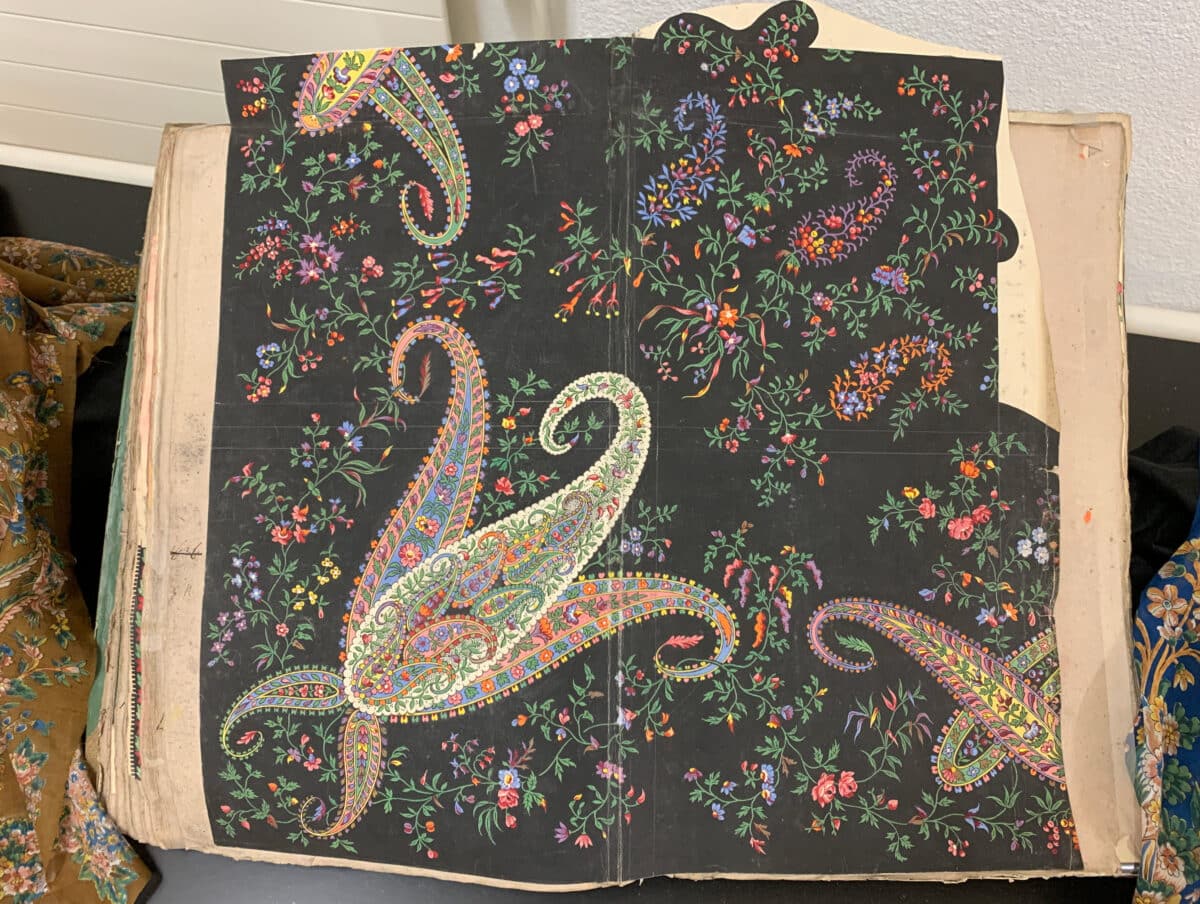

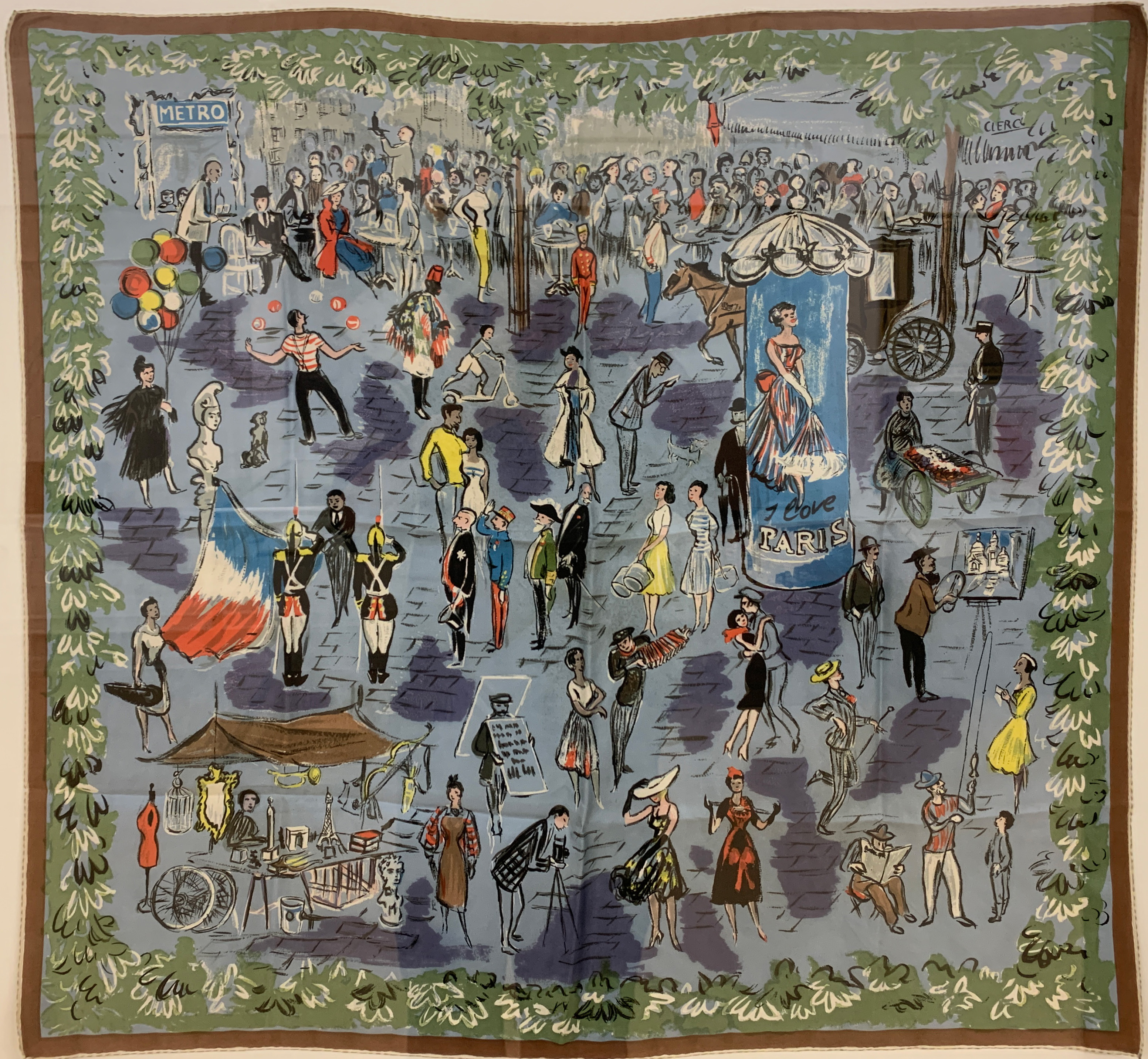

The first room reveals the story of Peter Blumer (1771-1826) who crossed the mountain pass at the end of the valley into Canton Uri and beyond to the south and Italy to found, at the age of 17, a trading company in Ancona. Blumer’s journey from the rural Swiss valley to the edge of the Mediterranean eventually extended across the world to east Asia and, as the mythology unfolds, included a visit to Indonesia and an encounter with batik patterned textiles. The elaborate process involved in batik-making meant that these fabrics were too costly, and therefore desirable, for the majority of people. Upon returning to Glarus, a method for reproducing the image if not the process of batik created the unlikely situation of cheap Swiss labour producing goods for an east Asian market. Unlikely, but of course commonplace within the cultural and material exchanges of 19th century colonialism. As Kindlimann pointed out, Switzerland had no colonies of its own, so was able to make use of everyone else’s without the expenditure, adding Latin American and African sources to the more familiar and widespread Asian references permeating European culture.

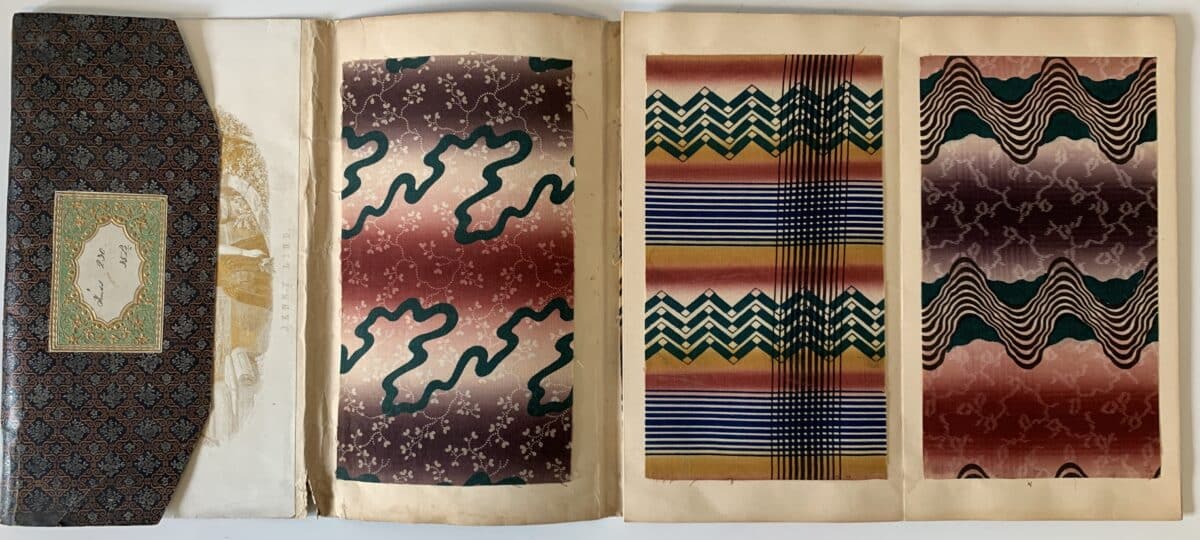

These become more apparent in the second room of the museum, where a range of textile products from different countries are on display. These are shown alongside sample and pattern books, records of trading and research journeys including letters and journals, analytical information, and examples of stationery and advertising for the different companies represented in the archive.

Courtesy of the author.

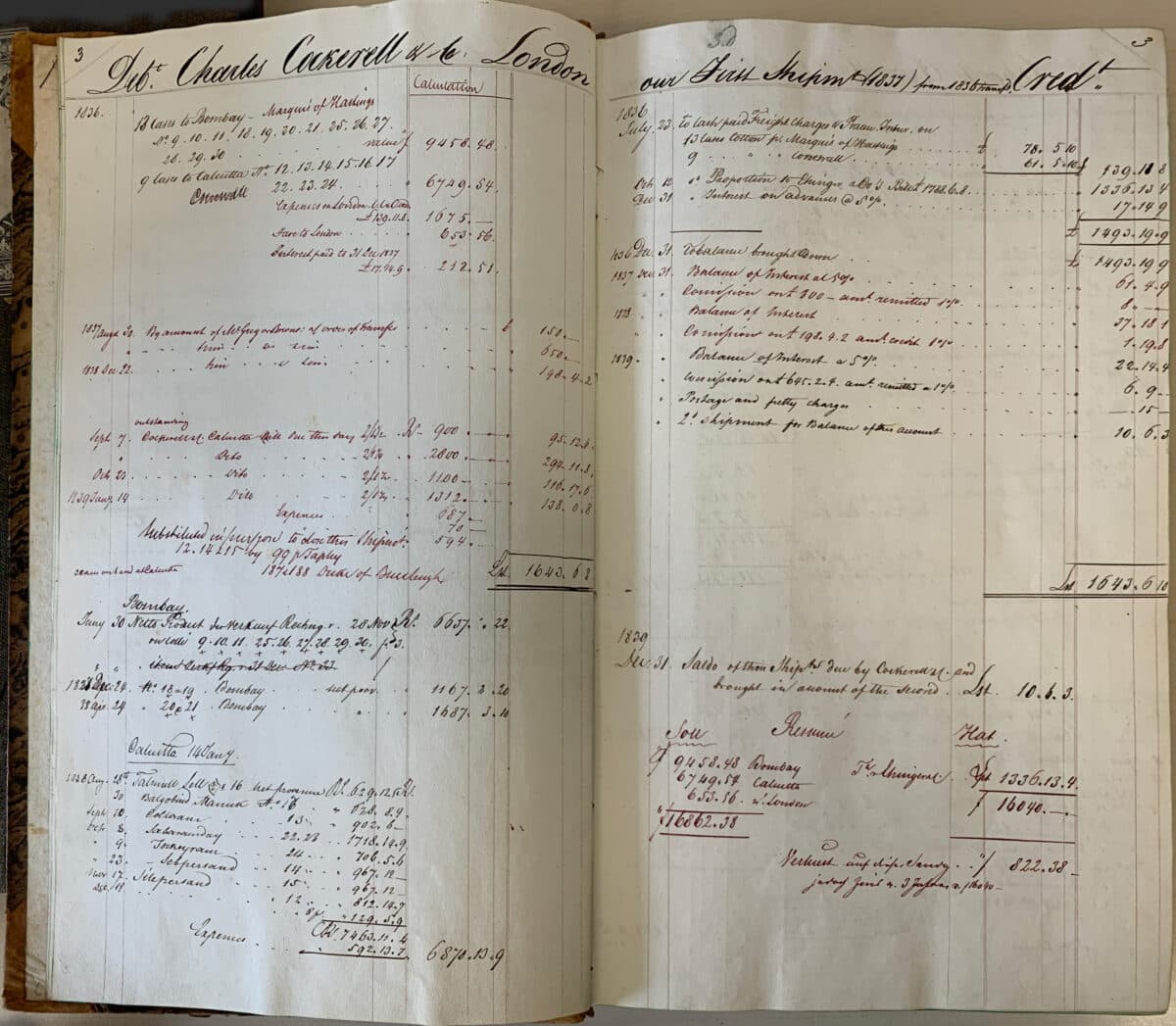

Courtesy of the author.

In July 2013, I made a research visit to the Wirschaftsarchiv in preparation for a workshop. Having found the online catalogue both informative and confusing, as is so often the case, I asked to view material around the journeys that were made between Schwanden, Glarus, and destinations in east Asia, without making specific object requests. I mentioned ships, I mentioned architecture. On the day of my visit, I was greeted by both Kindlimann and Stocksa, before being shown to the archive reading room and asked to put on white cotton gloves. Hoping for maps, letters, even drawings, I was presented instead with a pile of large leather-bound volumes. Bemused but intrigued, I opened one up to encounter on the first page the name Charles Cockerell. Alas, not the architect as I first hoped, who would have opened up the archive’s value for historians of British architecture, but the slightly earlier Charles Cockerell (1755-1837), first baronet, agent of the British Empire in Bengal, and friend of William Hastings, who is mentioned on the first page. Although not the coup for architectural history that first leapt into my imagination, this colonial relationship provides an insight into all the tiny, local links in the chains of colonialism essential to understanding its continuing impact on the world, and architectural history in particular.

Helen Thomas is Reviews Editor at Drawing Matter.

The museum is open to visitors on the last Saturday of the month, 14:00-17:00. Visit the Glarner Wirtschaftsarchiv website find out more. To arrange a visit (English or German): info@glarnerwirtschaftsarchiv.ch