Hexenhaus (2021) – Review

‘THE FOREST THAT BUILT THE HOUSE’

There are two drawings for me that are significant in understanding the work of the Smithsons. Both are of Upper Lawn [1]. One is a drawing made by Peter Smithson of their Solar Pavilion in elevation, the other by Alison Smithson in plan. The first drawing places the pavilion against the elevated horizon of the garden wall, with its great perched hedge bird and ceremonial flagpole. The building is seen adrift on the gentle waves and ridges of the garden. The elevational screen of the building is read in relation to the three tall trees, edging Macbeth-like towards it, while in opposite polarity, and in section, a well reaches down, deep into geological time. The plan by Alison Smithson, called ‘building and garden as one assembly’ is a beautiful patchwork of textures, paths and surfaces, a map of magical places, into which the pavilion is woven to form a constellation of things. Part of the importance of this second drawing is in knowing that the hand that drew it is also the same hand that has selected, composed and laid the setts and stones (with their geological traces of the old house) into patterns, and tended and shaped the garden. The trees in the second drawing can now be seen as markers of time. Shifted from elevation into plan, their concentric, clock-like rings are drawn into playful associations with all the other patterns and surfaces of the drawing.

Few drawings, for me, have captured and mapped a place more vividly, more poetically, more imaginatively than these two drawings. I think of them as somewhere between the fieldwork drawings of an archaeologist and an invitation from a child to begin an impromptu search with their treasure map. They encode a sense of time and of discovery. They reveal the rewards of the slow, meticulous observations gained from living within a place and reconstructing it through drawing.

Seen together, the drawings suggest different but contingent views of the same world; overlaid in thought but inextricably intertwined. They are set out facing each other in the book, The Charged Void: Architecture (2002) [2] as part of a carefully structured sequence, introduced by only four lines of Beckett-like brevity, which say more by what is left unsaid, by letting the drawings speak. But it is the trees that play a significant role. As has been identified by others, and by Peter Smithson himself, there was no such thing as just a tree to the Smithsons. There were only particular trees in particular places, always drawn with extraordinary care. Either existing or to be planted, each tree was a manifesto. In an earlier publication, The Shift (1982) [3], the tree was one of enquiry. In the 70s, Christmas trees captured the temporal: the colourful decorations and patterns of festival celebrations. There were trees that shaped the architecture by their very presence; physically at St Hilda’s in Oxford, 1967, and imaginatively in the drawings of the Yellow House, 1976. It was the dance with and around the existing trees that shaped and shadowed the evocative folding façades of the unbuilt Lucas HQ competition, 1974, a project that though unbuilt, took on an extraordinary presence as an installation.

At Upper Lawn, the large trees on the drawings beckon and signal from a much larger landscape. The notes on the drawing by Alison Smithson refer to just two things beyond the wall: the woods at Fonthill and the ruined abbey; living trees and abandoned stones. Inside, the folly remakes and reconfigures this. A fossil-tree of concrete is carefully balanced on the remaining ruin of the stone wall and chimney. It holds and supports a wooden treehouse (photographed appropriately with children playing inside). The first, an inanimate tree, enables the second living tree to come alive with its shifting ‘foliage’ of doors that open and close with the seasons.

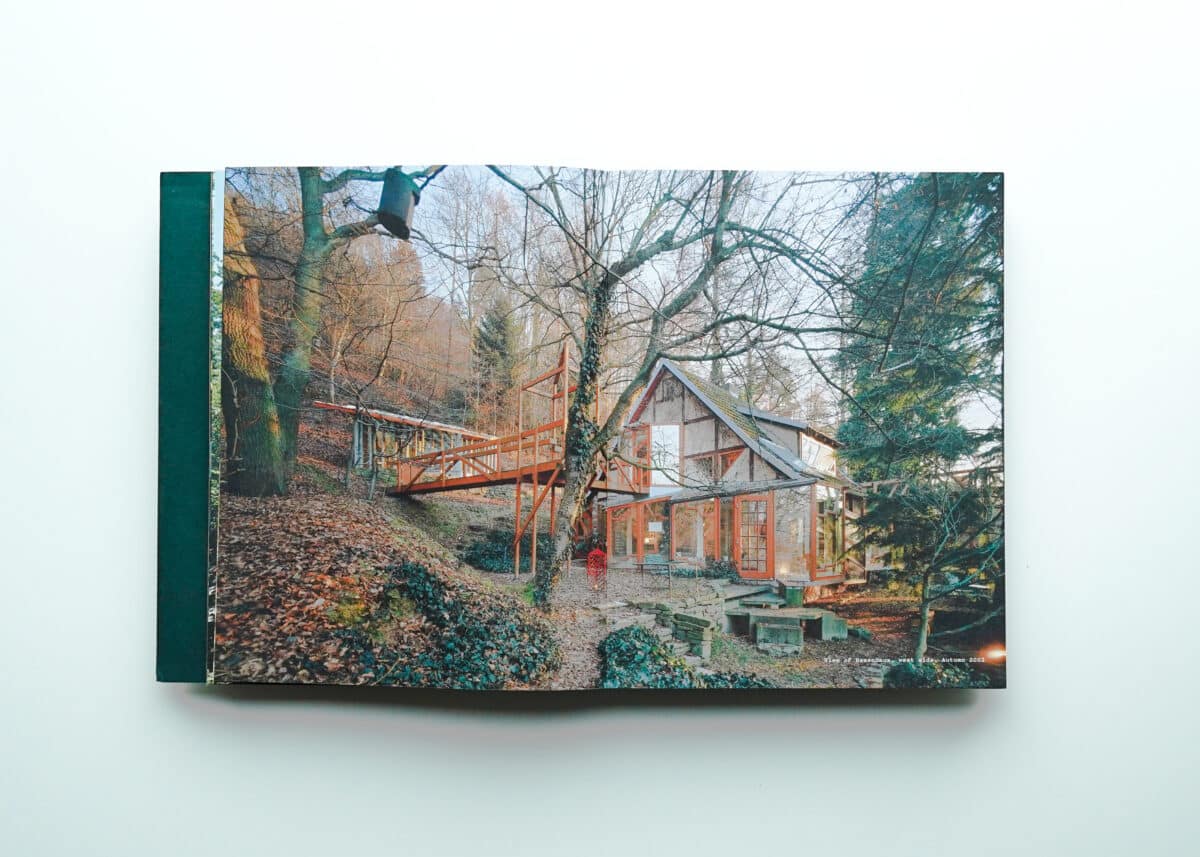

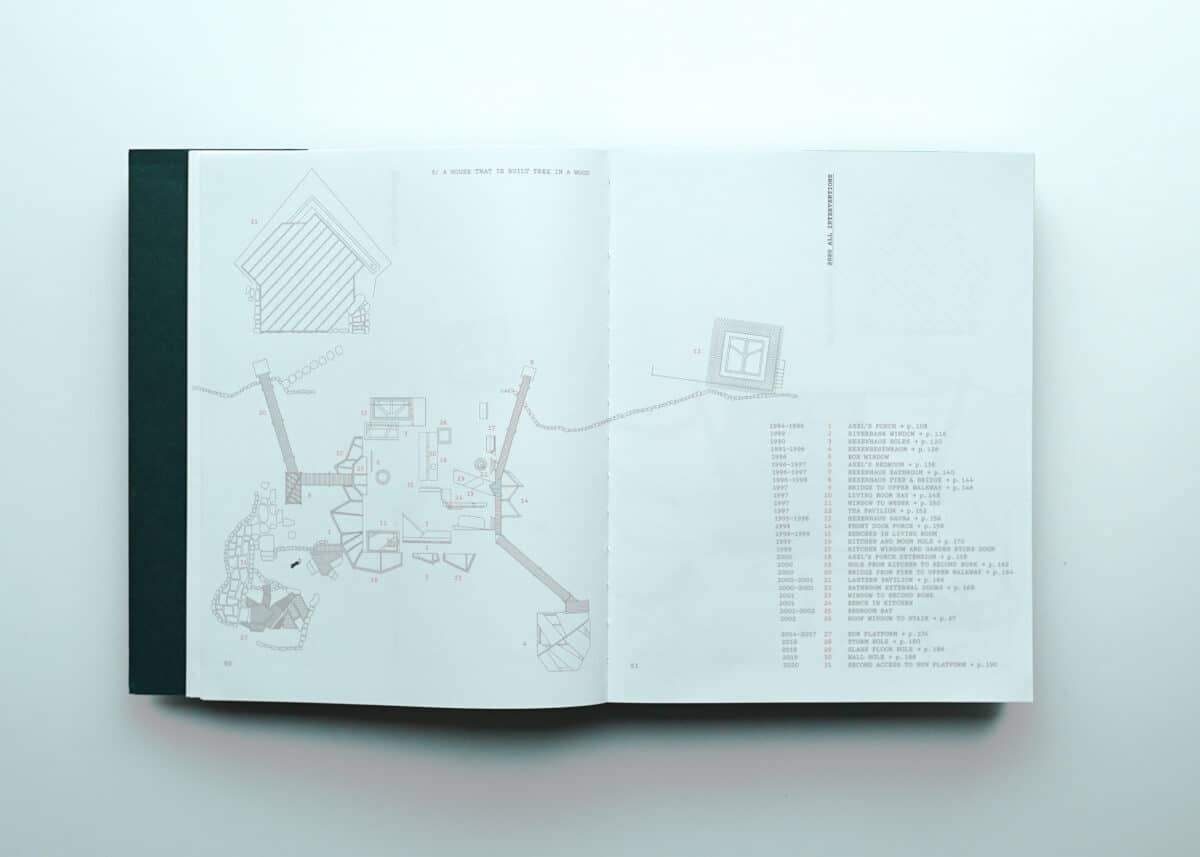

The subject of the book Hexenhaus: A House for a Man and a Cat (2021) is a house made within the Smithson’s forest and from out of their sense of the geography of a tree. This Hexenhaus (Witch’s House), as it was called by the locals, grew from an existing building set amidst a forest associated appropriately with the Brothers Grimm, on the edge of the River Weser in lower Saxony. This was a simple traditional house typical of the area, built by a sea farer and traveller, before being purchased by Alex Bruchhäuser. The house was the unlikely beginning for an extraordinary sequence of architectural interventions that parallels in duration a similar extended period of reflection and occupation by the Smithsons at Upper Lawn, becoming a dwelling turned inside out and upside down by their forest.

In Bruchhäuser, the Smithson’s found their perfect accomplice to this long adventure set in the woods, with its seemingly endless yearly episodes and multiple authors. Bruchhäuser’s passionate sense of design and the craft of making modern furniture came from his engineering background in East Germany, which he left in 1972 before setting up the Tecta Factory. His admiration of the Smithsons’ oeuvre began when he saw the Kingsbury Lookout project published in The Shift, and developed through conversations with Stefan Wewerka, who was working with him.

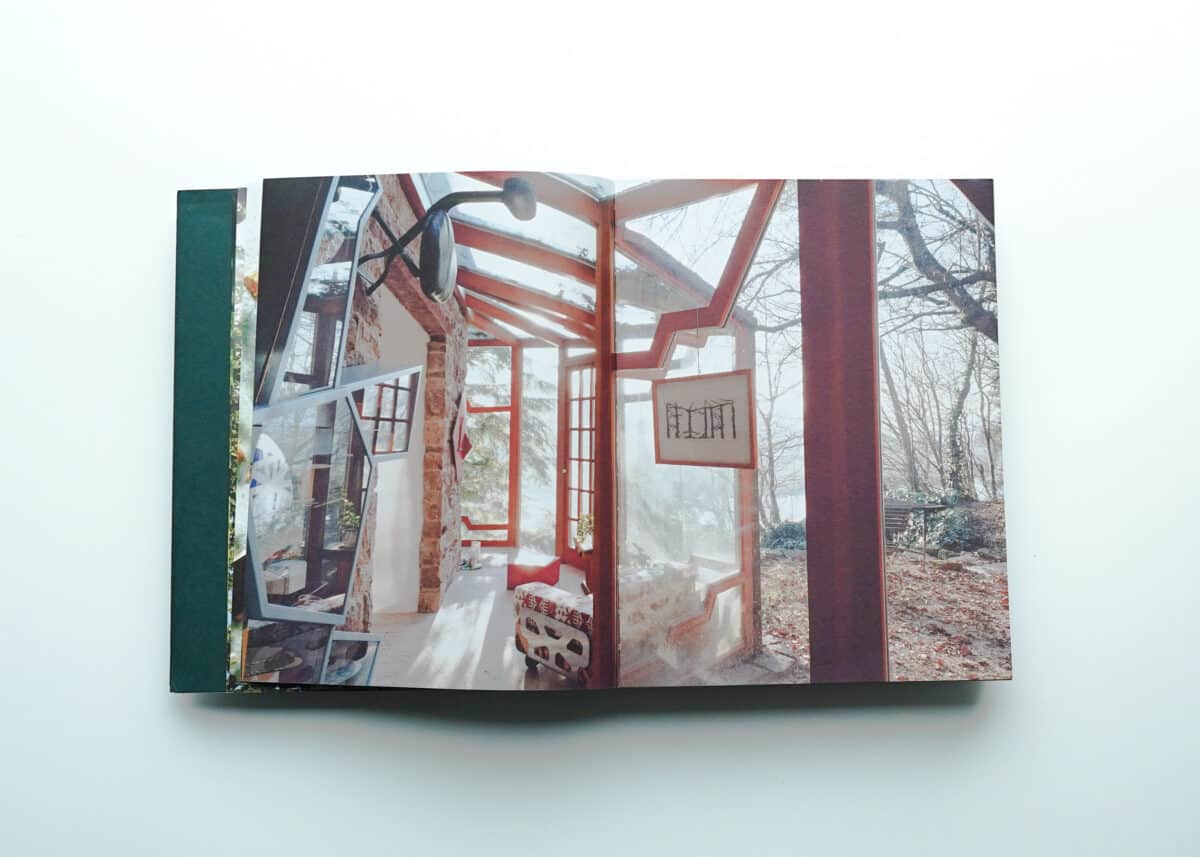

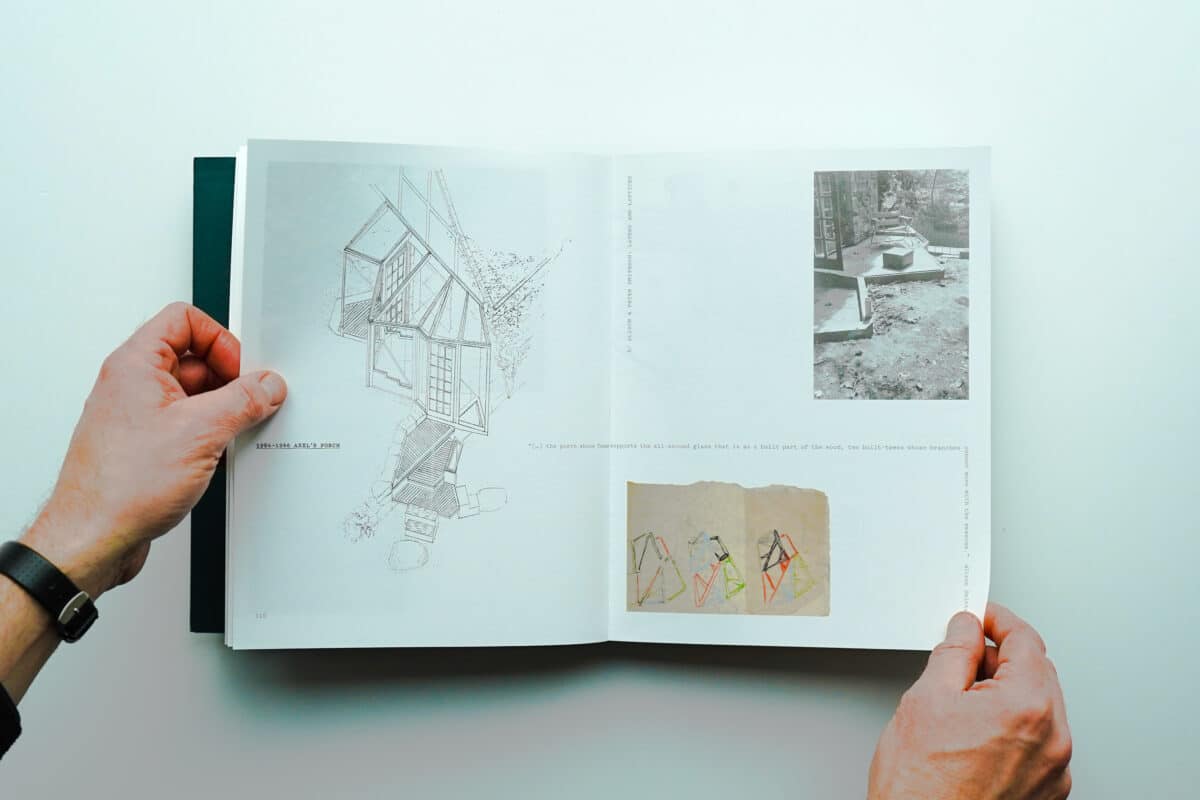

Following earlier plans to build a Miesian house on a site adjacent to the factory, abandoned due to local regulations, an existing house (the Hexenhaus), sited nearby was purchased with a view to adapting it. Bruchhäuser’s collaboration with the Smithsons began with a small simple request: to make a porch for him and his cat that would allow them to be inside, but to feel that they were outside, within the forest. So began a series of proposals and constructions that would evolve over almost 30 years in unexpected and unpredictable ways. Each summer, until her death in 1993, Alison Smithson, who became the principal author of the works, would journey to the house with new responses to Bruchhäuser’s requests. Her work was continued by Peter Smithson and their son Simon.

Louisa Hutton, in her book Godparent’s Gifts (2005) [4], suggests that the Smithsons’ work was essentially non-visual in that it was not driven to achieve particular preconceived images, or forms. Instead, responses were conceived firstly as ideas that then found form, and not the other way around. These were ideas which evolved from memory and association combined with the unique nature of their discoveries of specific places. But also, and importantly, they came from within the body of their own existing work, which looked to a process of recursive continuity. A tree planted in one project might well seek growth in another. Their work was not about object making, but about the space between things: voids for inhabitation and the uncertainty of unfolding events, which allowed for time as one of the critical agents to appropriate and shape events and spaces. This aspect of the Smithsons’ work leads in part to the difficulty of its reproducibility and understanding by a subsequent generation. Their drawings, though often and perhaps inadvertently beautiful, were usually simply a means to an end: a setting out of the rules of a game. They were forensically precise when for construction, yet curious and difficult to interpret immediately in terms of their design intent.

Hexenhaus: A House for a Man and Cat approaches the task of gathering the myriad diverse information on the house by carefully and playfully sifting through it in an almost collage-like way that is not dissimilar to that of the Smithsons’ own modus operandi. There are, as is to be expected, gaps, shifts and twists. We can see between things. To compile a book about such a complex house, evolving as it has over many years and through many different conversations, and authors, requires considerable editorial and design ability. This is also necessary not to become lost in the unpredictable directions and multiple interventions of the finished house. Any attempt to approach this subject through a conventional publication format would immediately fail in doing either the house or the Smithsons’ work justice. The book inventively gathers in and plays continually with different ways of seeing and reading the house. Perhaps it is a deliberate provocation – a complex compendium made to trigger associations, like Alison Smithson’s own collage and scrap books.

Upper Lawn. Solar Pavilion – Folly, the small booklet [5] compiled by Alison Smithson with Enric Miralles in 1986, reveals how a book can play with the life of a house. It is like a game of hide and seek that presents momentarily-captured perceptions that are framed like small postcards sent from within a house. It recalls, perhaps, Charles and Ray Eames film House: After Five Years of Living (1955) [6], which was an animated collection of stills set in motion through a filmic lightbox: a game of light and shadow, of catching of the shapes of passing clouds, finding alphabets in the shape of different things, the mapping of impromptu collections. The viewer is asked to look again at the ordinary and overlooked, such as the pattern and shapes of dishes in the kitchen sink, and there is a delight in the micro- and macro-world of everything seen inside and outside a house. The influence of Charles and Ray Eames was considerable on the Smithsons. In turn, the making of this publication (and the Smithsons’ work overall) was to have a big influence on the work of Enric Miralles and Carme Piños.

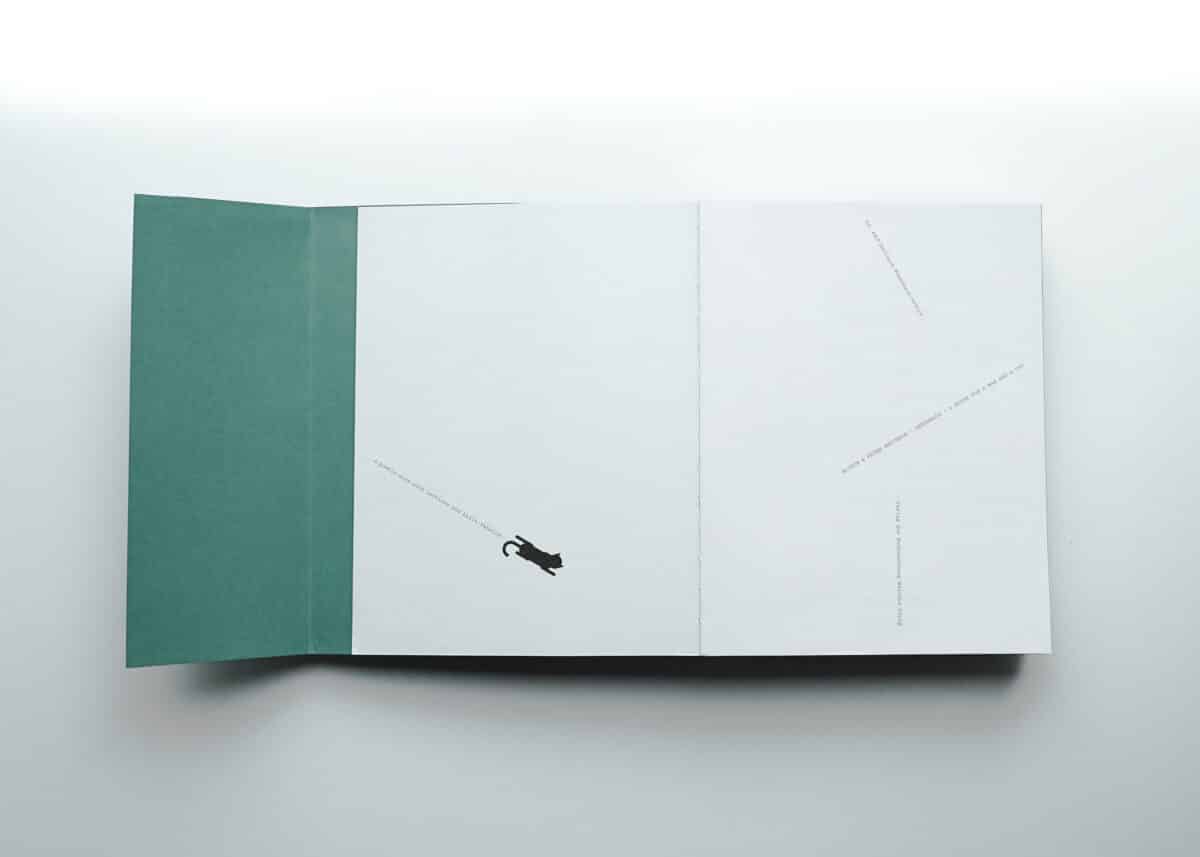

Hexenhaus: A House for a Man and a Cat begins with a cat darting across a page to begin a chase through words, drawings, photographs and ideas. Two further cats: the client’s cat, and the architect’s cat, Sir Karl and Snuff, are in correspondence and the two letters which initiated the commission are presented like two cats sizing each other up. The first cat, the cat of the book, continues to wander through the pages leaving tracks, trails and typographic traces for us to follow.

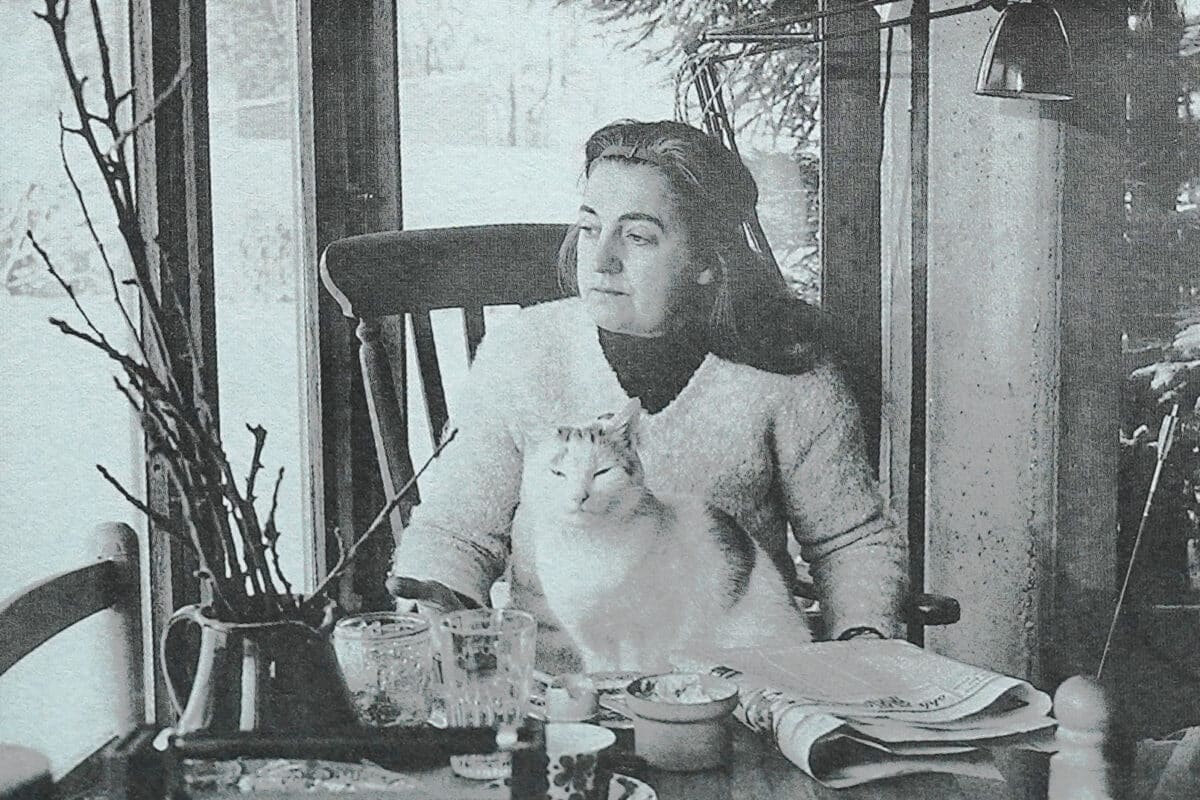

The story of the Irish monk philosopher and his cat Pangur Bán, which entranced poets like W H Auden and Seamus Heaney, comes to mind. It is based on a ninth-century poem about a monk and his cat who are united in eye, hand, pen and paw; poised and ready to pounce in the hunting of prey, which for the scholar is thought. Instinct and intuition are held in balance, with the monk in search of inspiration envious of the other’s ability. The photograph in the book of Alison Smithson with the family cat at Upper Lawn captures perfectly this relationship. Surrounded by the composition of the morning’s breakfast table, Alison is deep in thought. Outside, the snow-covered garden acts as temporal backcloth, while inside the cat sits magisterially warm, intently focussed on the camera’s eye. We, the readers, are entranced and bound to follow this feline intelligence and craftiness.

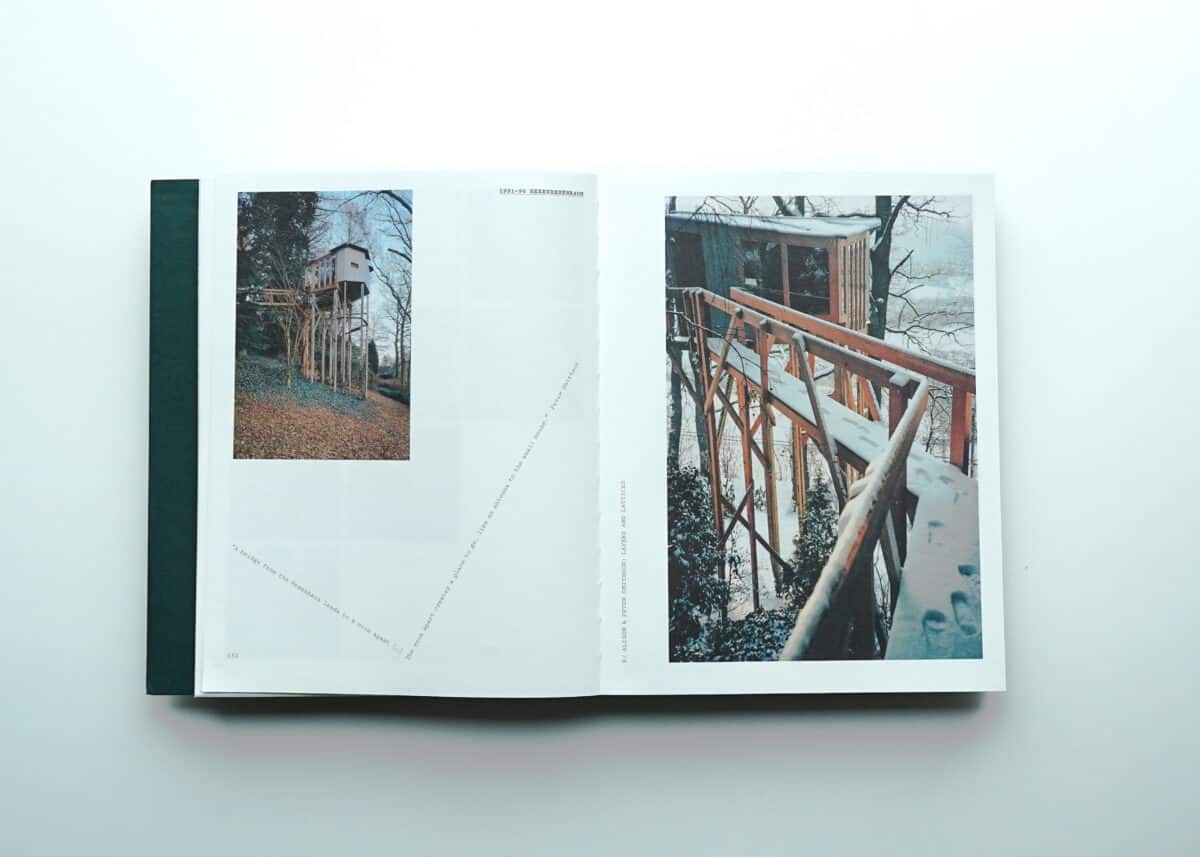

High up, across a bridge we begin our photographic journey into the house and book. Architecture emerges from within the forest. The book’s cover acts as the forest’s foliage in its deliberate and unravelling layering, held in the hands. The chapter headings provide small paths to explore, with crossroads of words and themes as multiple trajectories setting off in different directions. While this is essentially a visual book, the numerable texts within it bring considerable scholarly insight. Maddalena Scimemi’s essay, for example, is a careful and welcome guide to stop us getting lost. It takes us through the history and the evolution of the house. It provides an important understanding into the commissioning and the different stages of the house’s development. Ana Ábalos Ramos’ essay explores a more narrative sense of interpreting the house, where the layers and the structure of the forest and house replicate each other in similar patterns of growth, and where the surrounding satellite pavilions of the house define the boundaries of an extended territory, thrown like the seeds from the tall trees.

Visits to a private house such as this one are rare, and so the book provides an important way into a very private world, now turned inside out and mapped in bibliographic space. As a physical thing, the book is beautifully produced and printed. It is a crafted and tactile experience like the house itself, something to be explored and discovered, rather than to be read in sequence. The 14 sections of the book are perhaps only clues, with nowhere really to begin or to end. The Smithsons we know, saw the making of books as a central part of their work and its own form of architecture.

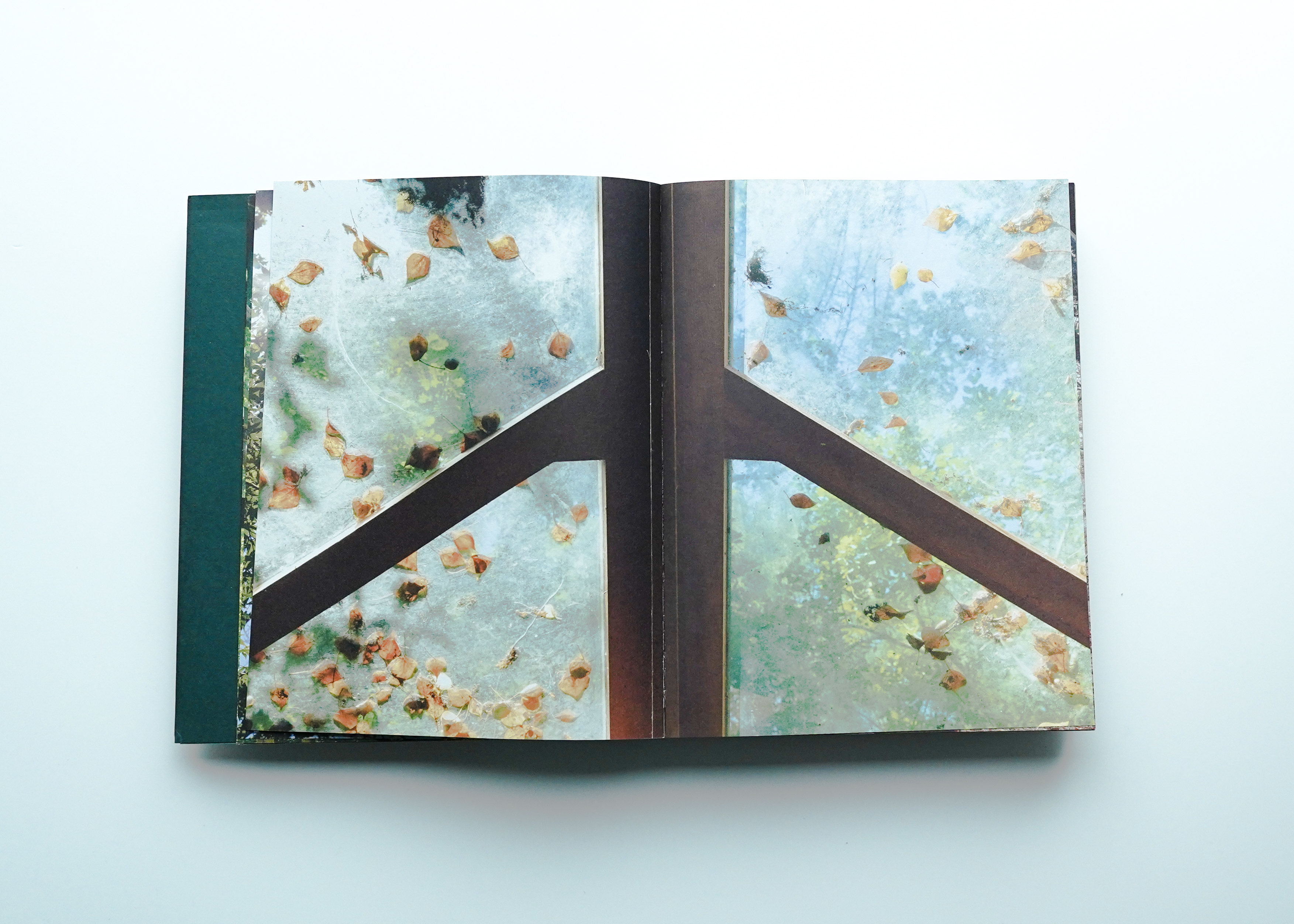

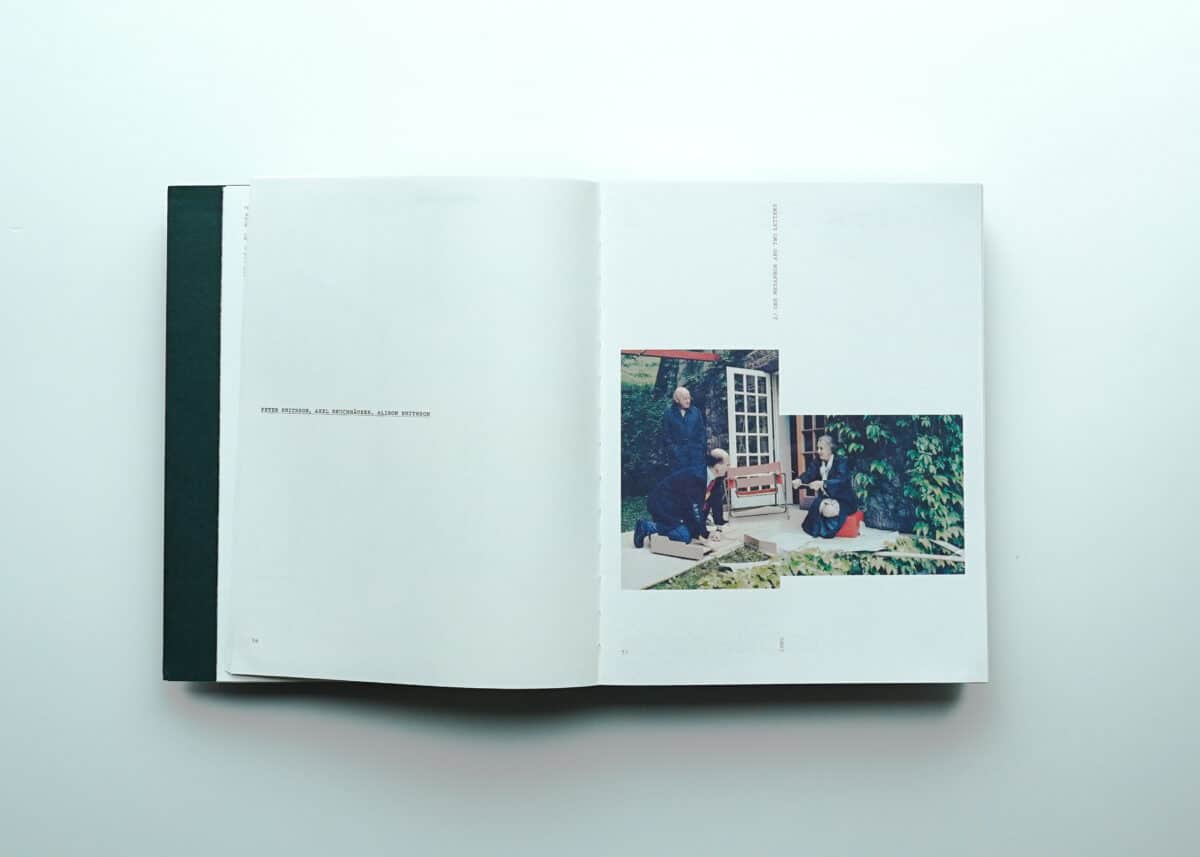

Alison and Peter Smithson themselves first appear in the book like magician dressmakers. Depicted alongside Bruchhäuser, they are testing a pattern for the porch at one-to-one scale, which is being thought out and laid out like a piece of furniture moved outdoors. Furniture is the actual starting point and the register of scale, as revealed in a photograph featuring a Marcel Breuer Wassily chair. For me one of the most beautiful parts of the book appears in a section called ‘an architectural allegory’. It is composed using photographs taken by the Smithsons themselves. Held timelessly in the soft glimmer of Kodak colour slide photography, it recalls the Eames’ film stills. Reflections on reflections, and connections made between and through the layered space of the architect’s imagination, eye and body, are held momentarily reproduced in their interventions like lenses. Perhaps the dream of having a Mies house, imagined originally by Bruchhäuser has become translated by the Smithsons into looking glass fragments in which prisms and jewels are embedded in an open geology.

The house operates at different scales: as a series of pavilions; typologically like a bay window; as a series of bridges; or as a piece of ambiguous furniture uncertain in its own function. The additions and shifts can be read in relation to the Smithsons’ work at Bath University, where the giant monolithic mat-building of the university campus is reanimated, tuned and particularised by the Smithsons’ playful additions. Sensitive to orientation, aspect, and events their Team 10 sensibilities and responsibilities to the existing fabric re-tune the simplistic megastructure with their compass-like fringes and additions shifting north, south, east and west. Pavilions designed to draw our attention to what lies outside, in the world and beyond the restricting parti, culminate with the architecture building pivoting and swinging open like a welcoming doorway. The Hexenhaus is this in miniature, opening up in all directions like the Wishing Table they designed for Tecta.

Peter Smithson saw the house as a form of personal theatre, both self-analytical and psychoanalytical, through which the client/engineer needed to build and understand the reason for its own making and artifice. Epitomised in the Trundling Turk chairs that shifted occupation to the outside, architecture becomes a framework inhabited by life both inside and outside that includes the smell of leaves, the trees moving with the wind, and the witnessing of the movements of the sun and moon, all of which belong to an extraordinary, sensorial and magical ‘room’. With each seasonal change, the shifting winter foliage of the forest which encircles the house becomes an outer skin which is shed. Pulled back like a fabric in winter, the river and distant views are now revealed. The Smithsons’ sense of layering is not just architectural in intent. Seasonal time slips and overlaps in glimpses through the different apertures of the house, which is captured in the many photographs in the book, as a continuous game of light and shadow.

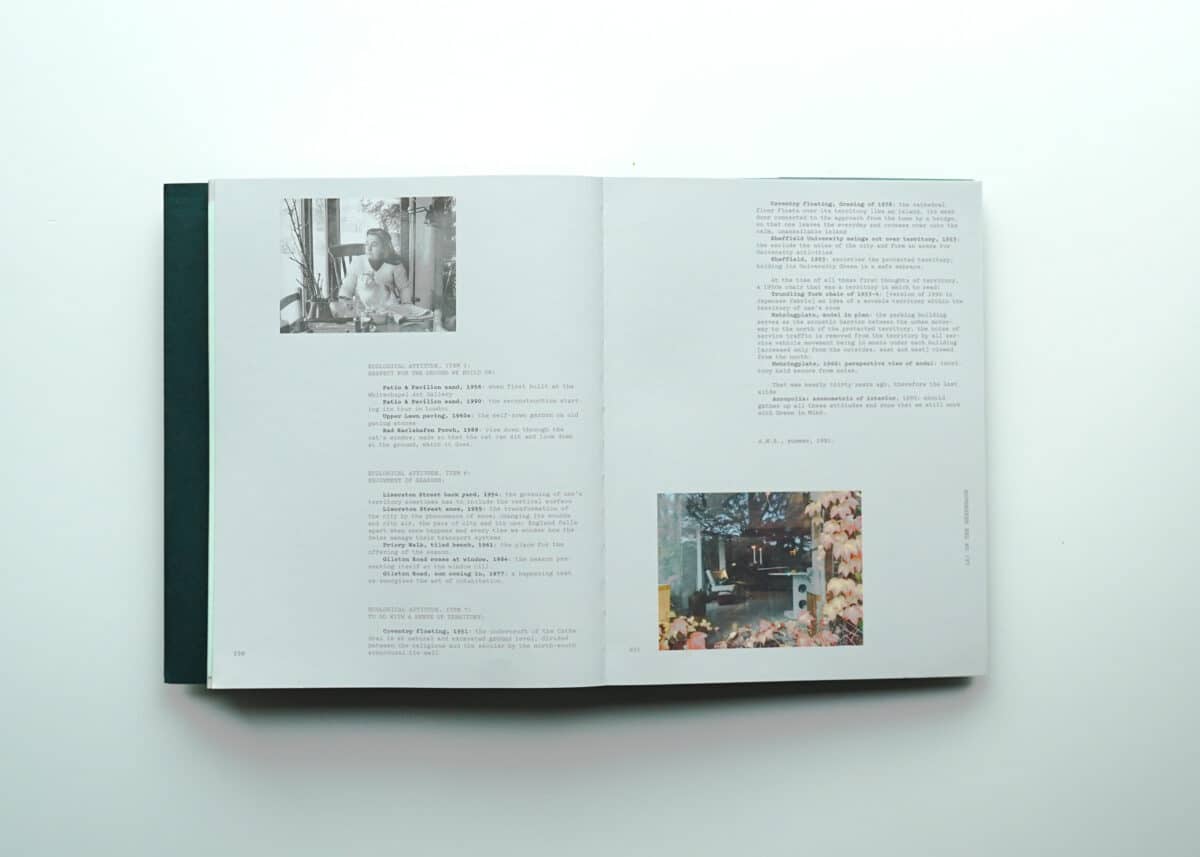

With green in mind (1991) [7] was a lecture given by Alison Smithson on the reconstruction of the patio pavilion, which is incorporated with a series of other written pieces by the architects into the book. It presents a deeper and richer sense of ecological thinking that includes the dissolution of the inside and outside, the sky as territory, the interdependency of the micro-climate, and the careful register of topography, which are all about a deep respect for the uniqueness of place and the wider environment. To read this now, some thirty years after it was written, is to get a sense of the importance and value of the Smithsons’ work in framing a richer sense of the total environment within which architecture operates. It takes us beyond simplistic mantras of sustainability.

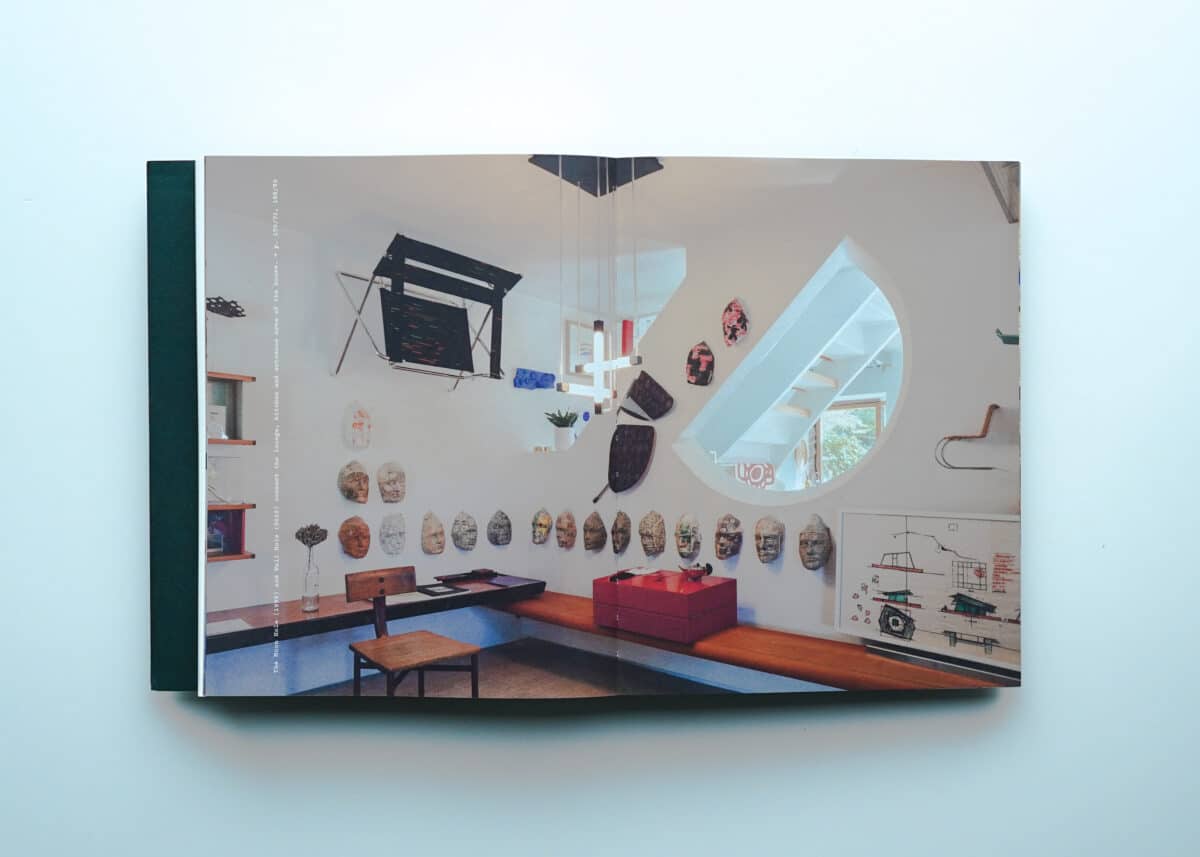

At times the inner space of the house seems overwhelmed by the collection of things within, like a kaleidoscopic swirl of artifacts taking over St Jerome’s study. Elements of furniture appear to defy gravity and their own function, shifting walls into floors, and ceilings into tables. Part prisoner to an expanding collection, part voyeur of it, the restorative energising cell is beginning to be lost. Beautiful though some of the works are – by Malevich, Albers, Klein and Calder, there are moments when you sense the trees want to reach deep into the house, and to try to take possession of it again, and to remind its owner that the forest is the true collection. The five lookouts designed in 1977 for the Kingsbury Waterpark competition, like five exotic birds of flight, are made from the ‘lost’ wood of the Dutch Elm crisis become the talisman for this project and the work at Tecta. They magically proposed to return the lost trees into a landscape of playful enjoyment and totems to climb and view the surrounding landscape. This is an alchemical inversion of disaster into delight.

The Hexenbessenraum (the witch’s broom cupboard) is perhaps the most extraordinary of all the interventions. It is one of five satellite constructions that exist beyond the boundaries of the house, which included the lantern pavilion, the tea pavilion and the sun platform. High up in the trees the structure levitates its occupants into a world of birdsong, ‘a kind of antenna feeling the land form’, was how Peter Smithson described it, and it captures the Smithsons’ own playful sense of homage and reverence to the work and influence of Patrick Geddes [8]. His Outlook Tower was a didactic and symbolic axis mundi, which was translated and transfigured in the design of Hexenbessenraum and later in the Hadspen Obelisk [9]. It is an outstretched tree asking us to look beyond the trees while at the same time deeply rooted within the forest. It mediates our capacity to both look inside ourselves and beyond to the surrounding world to measure and register our place and responsibility within it. We are at the height of the birds, deliberately turning around to look back at the house, and to wonder how we got here.

If the book can be interpreted in part as a sequential and metaphorical visit to the house, then we leave it as the lights begin to come on, as night falls, when it becomes a lantern of cut outs, glowing from within the forest. The ‘book cat’ makes its final dart across the last white page. Somehow, it has slipped through the physical space of the book into its back cover. Transforming itself in size, medium and dimension, the cat animates its own release. The more we read and hold the book, the more it shakes itself loose. We must follow the instructions printed beside it on the back cover: push out and put up. Like Panger Bán, it is the only possible interpreter of this whole story. It is the Tecta cat, an emblem and rebus for an extraordinary house and a remarkable book.

Simon Smithson, Maddalena Scimemi, Ana Ábalos (Alison and Peter Smithson) Hexenhaus: A House for a Man and a Cat (2021) is published by Walther König. Copies of the book can be purchased here.

Paul Clarke is Professor of Architectural Design at the Belfast School of Architecture and the Built Environment.

Notes

1. Upper Lawn is a weekend residence built by the Smithsons for themselves between 1959 and 1962. It is sited near Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire and often referred to as both Folly and Pavilion. The process of its construction and inhabitation is recorded in considerable detail by the Smithsons’ own remarkable photographs and drawings. Journeys to and from it are described in AS IN DS An Eye on the Road byAlison Smithson (first published by Delft University Press, 1983).

The building was faithfully and beautifully restored by Sergison Bates in 2004. For the most comprehensive documentation of the building see: Complex Ordinariness: The Upper Lawn Pavilion by Alison and Peter Smithson by Bruno Krucker (gta Verlag, 2002).

2. The Charged Void: Architecture compiled and authored by Alison and Peter Smithson (Monacelli Press, 2002).

3. Alison + Peter Smithson. The Shift, edited by David Dunster. Architectural Monographs 7. (Academy Editions London, 1982).

4. ‘Grandparent’s Gifts’ by Louisa Hutton, in Architecture is not made with the brain: The Labour of Alison and Peter Smithson (AA Publications, 2005), in association with the symposium held at the AA in November 2003.

5. Upper Lawn. Solar Pavilion – Folly (Barcelona, 1986) by Alison Smithson with Enric Miralles.

6. A House: After Five Years of Living, 1955. This short 11-minute film has music specially composed by Elmer Bernstein and begins with an animated sequence of the construction of the house. It consists principally of individual photographic stills brought into a carefully constructed sequence of filmic montage. A sense of the deep admiration the Eames were held in by the Smithsons is in part documented in Changing the Art of Inhabitation. Alison and Peter Smithson (Artemis, 1994).

7. This lecture was given in Buffalo, 1991 to accompany the reconstruction of the Patio and Pavilion project at the Albright- Knox Art Gallery. It provides a remarkable walk-though and insight to the Smithsons’ earlier projects using the seven aspects of their ‘ecological thinking’ as guiding principles.

8. Patrick Geddes, Scottish biologist, planner and innovative thinker, was, I believe, a considerable influence on the Smithsons. In The Space Between the suggestion is that knowledge of his work, apart from Edinburgh Zoo, was slow to filter through to them, and that it was his diagrams which were an influence on Team 10 thinking. The Smithsons’ comprehensive knowledge of Geddes’ Edinburgh project, which they referred to as an ‘educator’, and the city’s proximity to Newcastle suggest otherwise. Future research on this may reveal more.

9. The story of this remarkable project and working with Peter Smithson is told by Niall Hobhouse in Architecture is not made with the brain: The Labour of Alison and Peter Smithson. (AA Publications, 2005).