Insignificance 2: Distinction – Polysemy

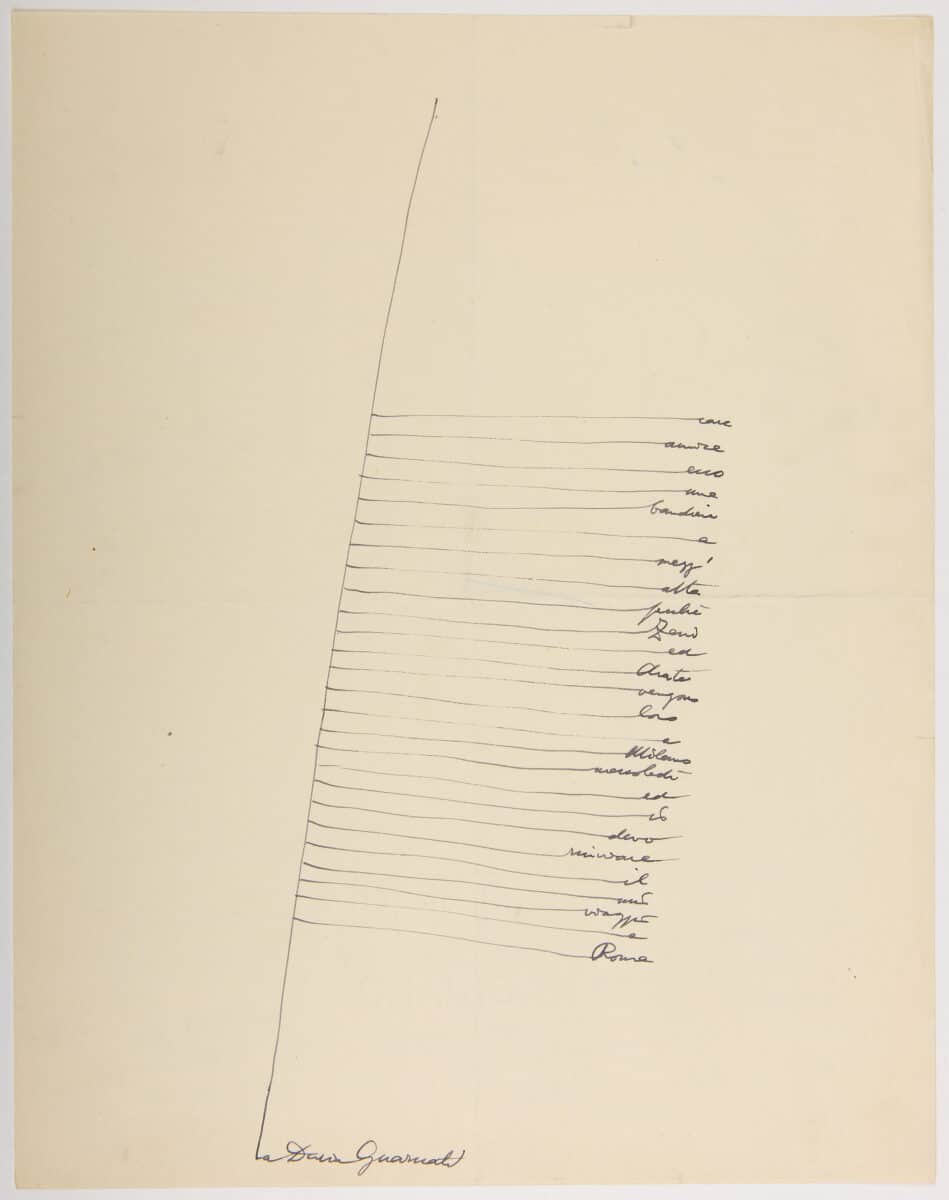

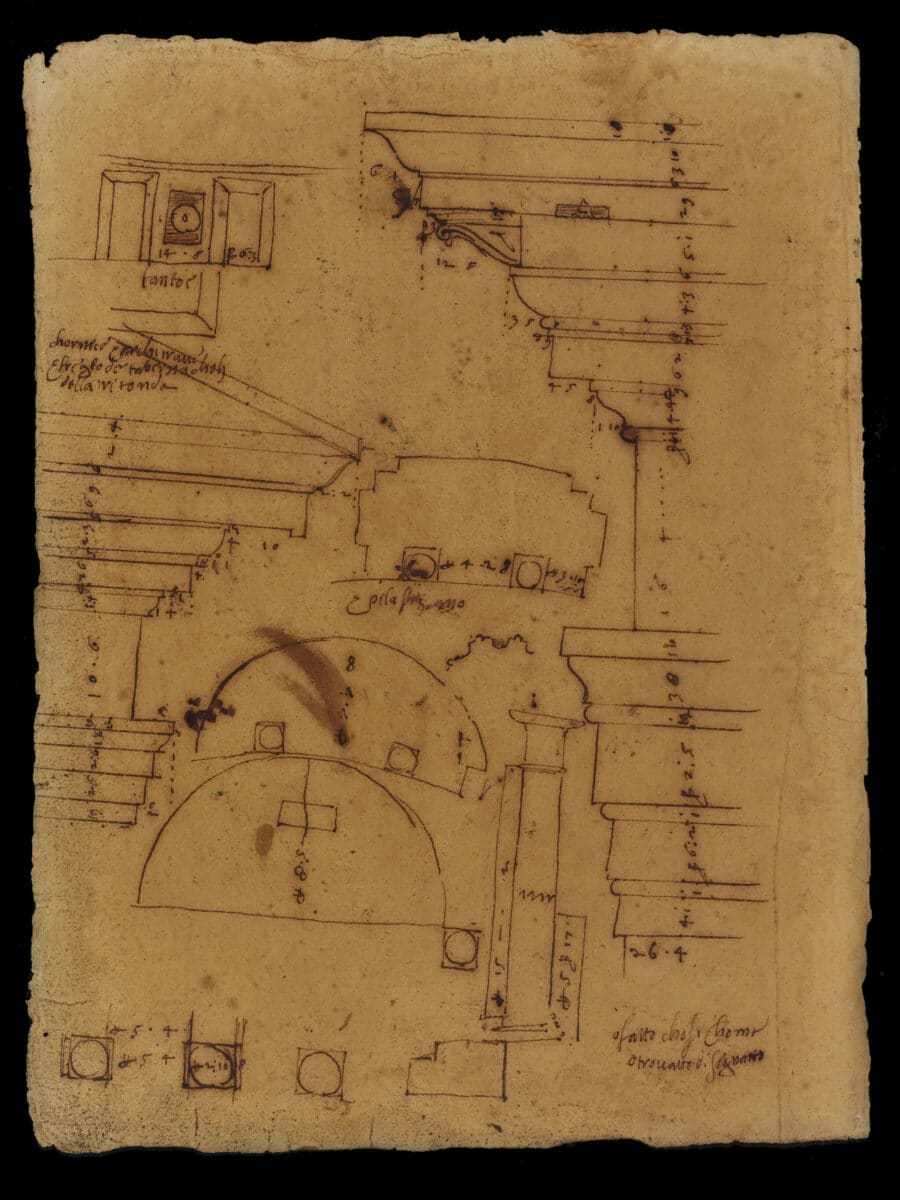

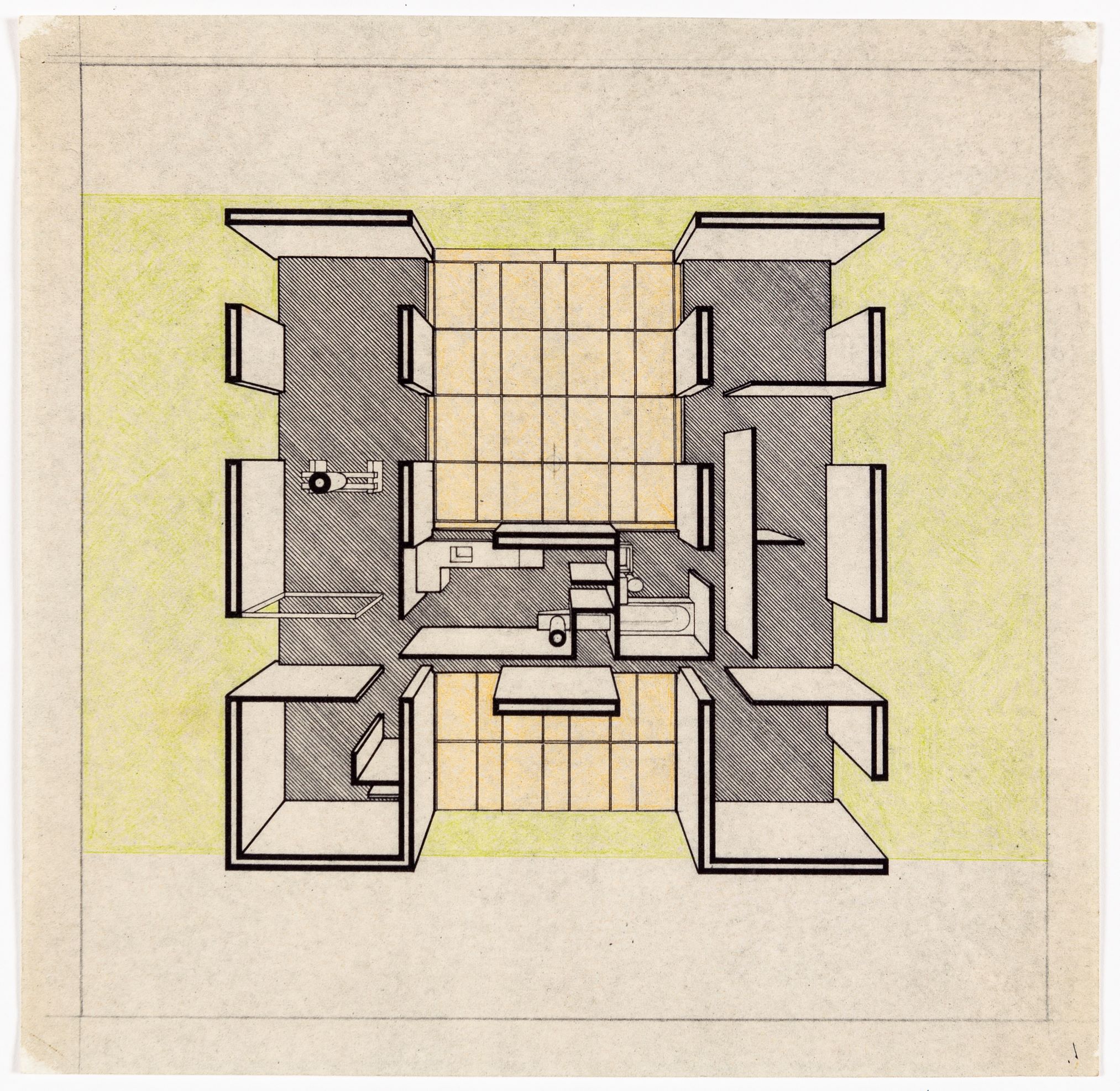

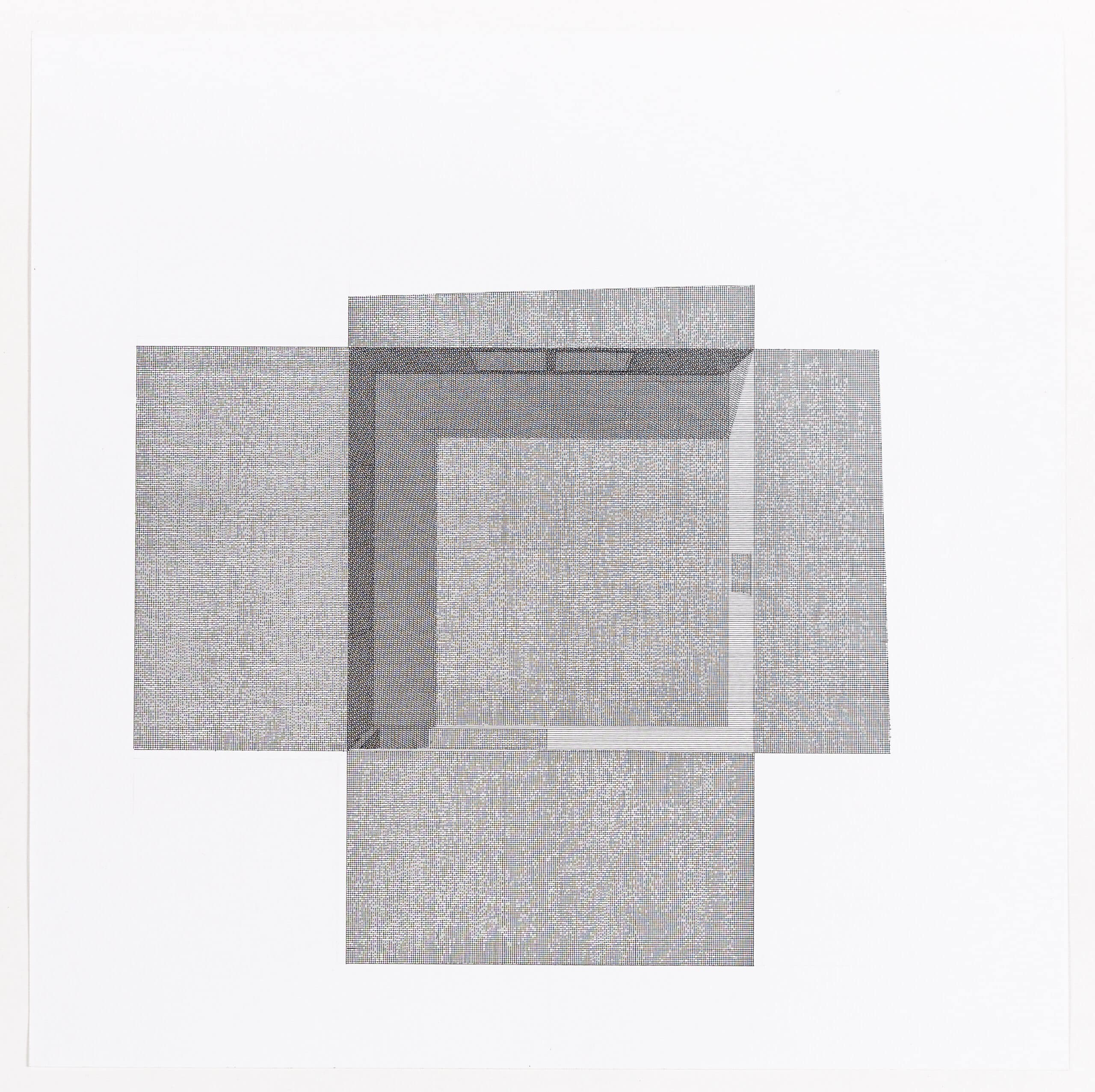

The following texts are excerpted from Gordon Shrigley, Insignificance: A short discourse on the physical and ideational economy of line within architectural representation (Solitude Editions, 1998). Now, twenty years after Insignificance was first published, Gordon Shrigley has revisited the publication for a series of postings on Drawing Matter. Each of these posts connect passages from the book with drawings in the Drawing Matter collection to extend the discussions set out in the original publication. Here, the texts are illustrated with images that suggested themselves to Niall Hobhouse as he read the text.

Read the first in the series here.

~~~

~~~

Distinction

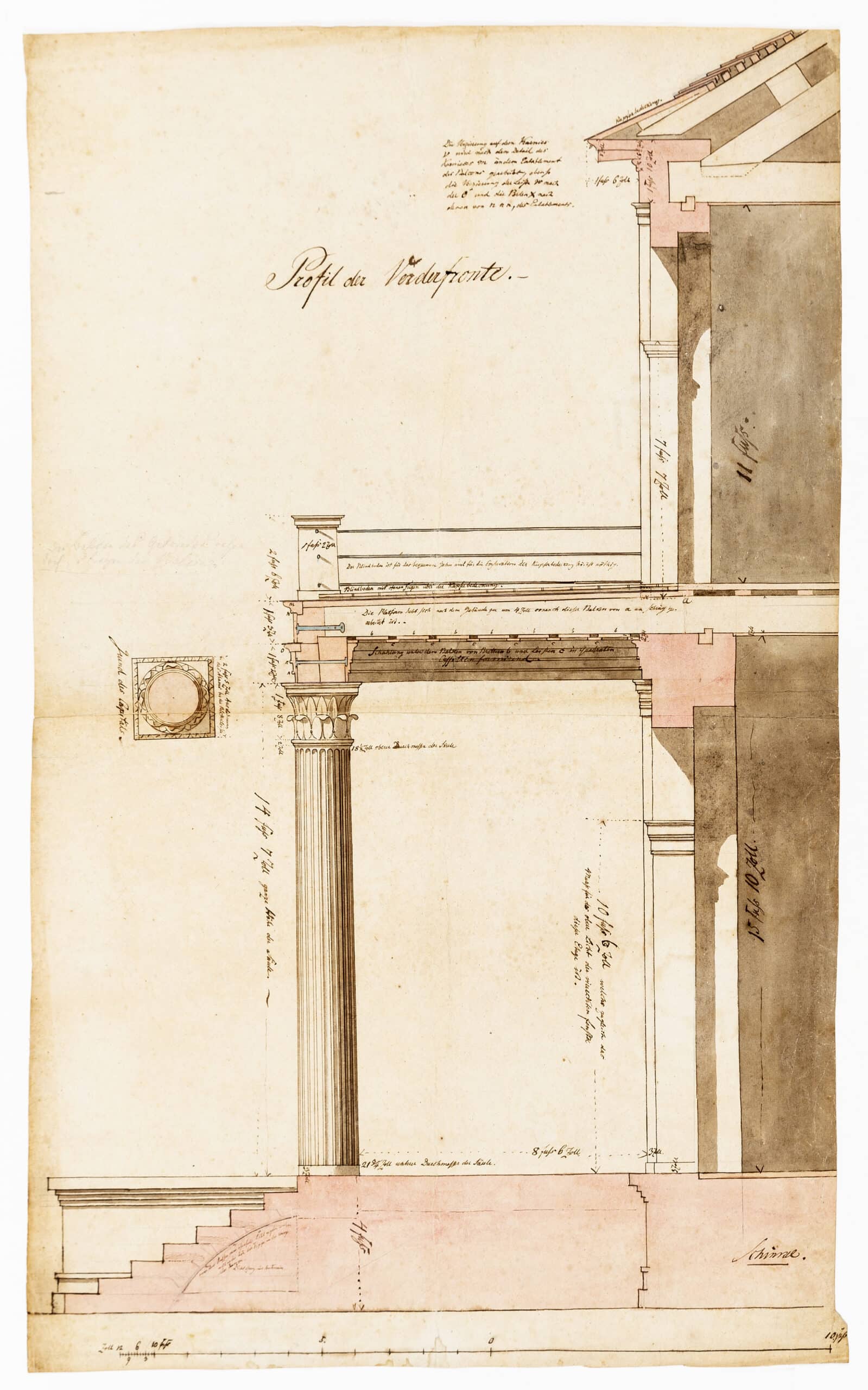

Architectural line practice distinguishes itself from similar line practices in its direct relation to a mode of production. [1] As a visual language, it

is required to assume a certain constancy, which seeks to forge an unobstructed link between thought (doxically conceived as the author’s

ideas transparently represented in the drawing) and action (as required to physically construct a building). The architectural line has been, and

is, tested as to its efficacy each time a structure of a certain complexity is realised.

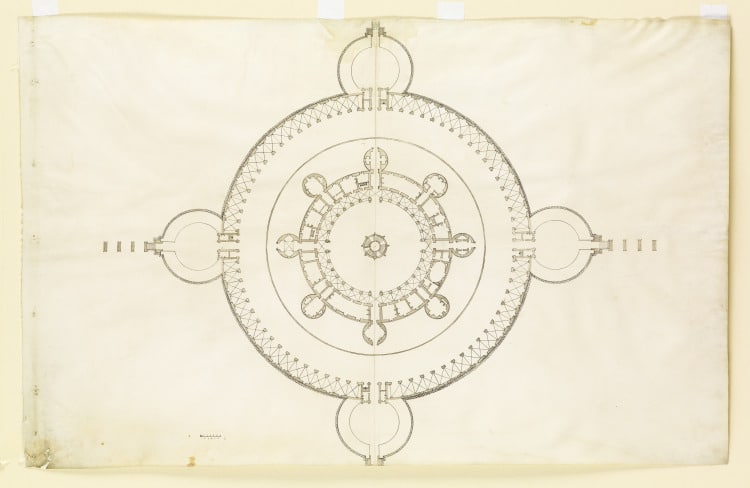

Throughout the unfolding of architectural history, the codes of line have been developed directly in relation to the material world (the laws of the place). In this sense, and in this sense alone, the architectural mode of representation can be seen to have evolved (to a greater or lesser extent) symbiotically: first line had to adapt to the world as given, as found; second, through an increasingly complex mode of production, materials available for construction were produced in direct relation to the discourses of line and its marked tendency to the rectilinear.

Note

- Line within architectural representation is qualitatively different from the autistic line of the fine arts, which does not necessarily have a need to establish a framework of compositional instrumentality and so can define the significatory aspect of line as particular if required. Although within fine art there is clearly a lineage of line, this, in retrospect, is not a unitary history, with many different line theories competing for representational hegemony.

~~~

~~~

Inhabitation

How should we proceed therefore to think of line’s purpose generically?

The architectural line inhabits a tripartite relation to culture through its mobilisation as either a didactic, hermeneutic, or involuntary

determination.

~~~

Doxa

Purpose is seen to act as doxa, [1] as an everyday motive, read importantly as not coterminous with the hidden hand of ideology (a false consciousness) but as a practice of aesthetic/political motivation, which is worked through in a conscious way (contrary to Pierre Bourdieu), but is nevertheless able to create a hegemony of tendencies, which allow authors/institutions not to have to relearn the processes/mechanisms of aesthetic/social determination at the moment of utterance/representation. This allows production to continue unhindered, yet purpose allows a working through of legitimate questions in and around the procedural mechanism germane at that moment in time. Here, line is mobilised as a neutral instrument, and is seen to impart no traces upon the primary processes and products of the architectural imagination.

Note

- ‘The social world doesn’t work in terms of consciousness; it works in terms of practices, mechanisms and so forth. By using doxa we accept many things without knowing them, and that is what is called ideology.’ (Pierre Bourdieu, ‘Doxa and Common Life, In Conversation with Terry Eagleton’, New Left Review, no. 191 [1992], 113.)

~~~

~~~

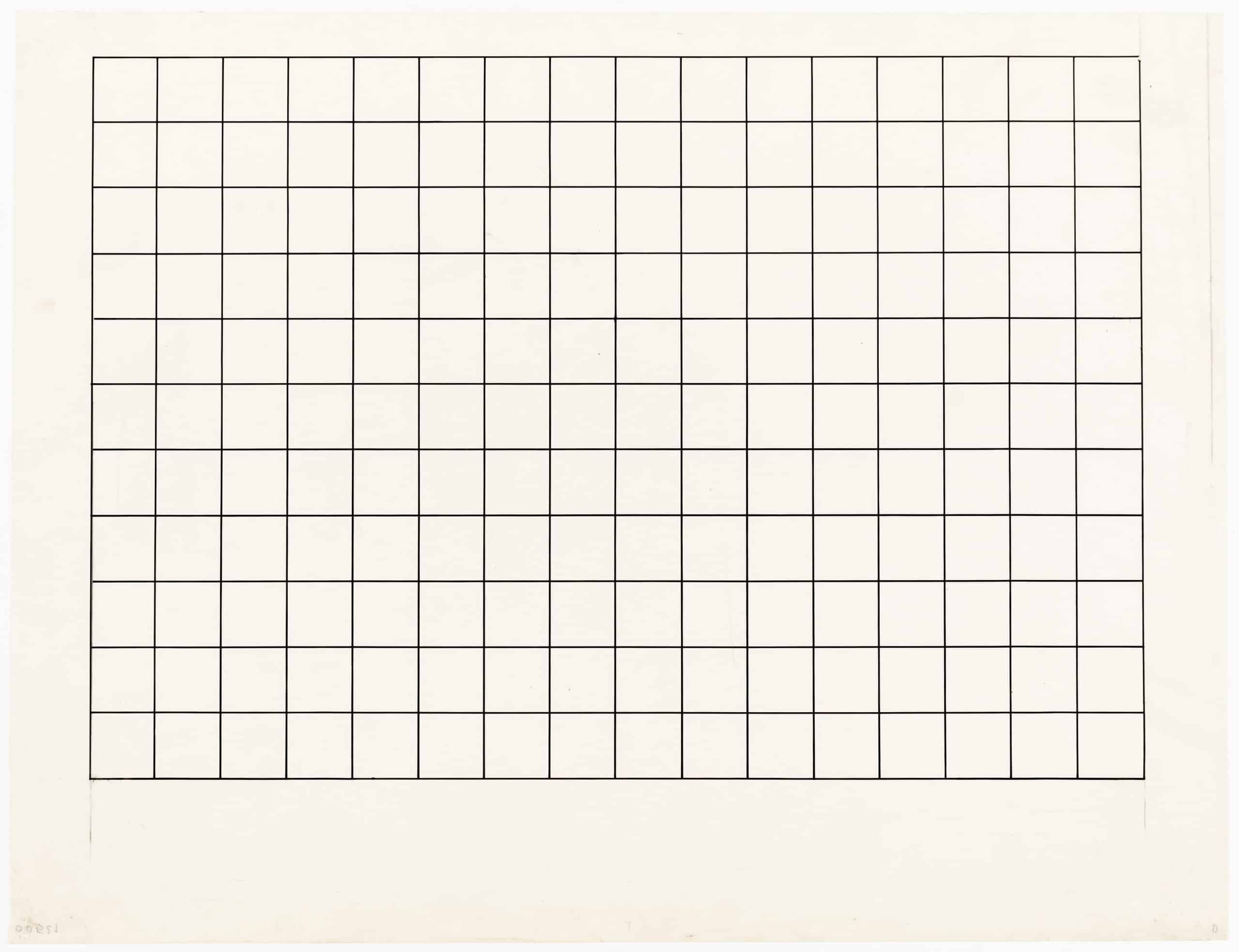

Immanence

I speak here of a perceived character to the contemporary architectural line outside of all determinations, be they that of an author, a tradition or an authority. And so, I would like to think of purpose in the context of the ‘purpose of line’, as opposed to, say, line in the service of an aesthetic modality or as one arm of a strategy for an industrial production. Line inhabits the theoretical possibilities opened up within the tripartite division between signifier, signified and sign. [1] And so, if we are willing to accept that the relationship between an object and its representation is historically contingent, and thus inherently unstable, are we not then, justified in looking for signs of immanence within the form of line? Otherwise line will be written as a lacunae, forever to be theorised as a passive, blank screen for instrumentally inclined projection, thereby leaving the material character of line as a convenient mystery. [2] Contrariwise, to start to explore the immanent actuality of line, is to situate the architectural line as residing within its own terms of reference, parallel and independent of an operating prescription.

Notes

- ‘Let me therefore restate that any semiology postulates a relation between two terms, a signifier and a signified. This relation concerns objects which belong to different categories, and this is why it is not one of equality but one of equivalence. We must here be on our guard for despite common parlance which simply says that the signifier expresses the signified, we are dealing, in any semiological system, not with two, but with three different terms. For what we grasp is not at all one term after the other, but the correlation which unites them: there are, therefore, the signifier, the signified and the sign, which is the associative total of the first two terms.’ (Roland Barthes, ‘Myth Today’, in Mythologies [London: Jonathan Cape, 1972], 112–113.)

- See Catherine Ingraham, ‘Lines and Linearity: Problems in Architectural Theory,’ in Drawing, Building, Text, ed. Andrea Kahn [New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1991]).

~~~

~~~

Polysemy

A line reading practice, which ascribes a role to the architectural line as contingently inside or transcendentally outside the human historical moment, both posit line as instrumental in character. Either line is directed by others (subordinate) or essentially by itself (dominant). Another reading, though, is left open whereby line is seen to be caught up within the particularities of cultural polysemy, not so much as a clearly

observable condition, but as located within a quotidian of competing involuntary mechanisms, procedures and tactics. This is to see the

architectural line, and so all culturally symbolic actions, as enmeshed within a unsurveyable field of unintended consequences, and therefore

possibly immune from crude determinist readings, which would seek to place the architectural line, and hence architecture itself, as being

essentially didactic or hermetic.

~~~

– Laura Bonell and Daniel López-Dòriga