Interview with Space Magazine

This interview was first published, in Korean translation, in SPACE Magazine. Drawing Matter would like to thank the editors of SPACE for allowing us to publish the English version of the text.

Semi Park: Drawing Matter is an organisation that explores the role of drawings in architectural thinking and practice. Upon what opportunity, when, and by whom was this organisation established?

Matt Page: Drawing Matter was established about ten years ago by the collector Niall Hobhouse, a trustee of the Drawing Matter Trust and the Director of Drawing Matter. It was set up to propose alternative ways of collecting and engaging with architectural drawings, based on Niall’s experience of working with large public institutions and museums. It began as a response to frustrations about the types of material that these organisations collect and how they display them, both physically and digitally.

A significant source of these frustrations is the design of institutional archival spaces. Often, they are sub-basements that are climate-controlled and artificially lit. They are environments that prioritise the preservation of the objects over the experience of the researcher, which in turn strongly dictates how drawings are studied.

The Drawing Matter collection is housed in an archive building at Shatwell Farm, Somerset, UK (designed by Hugh Strange; built in 2014). The building is a low-tech alternative to these archival environments. It is a single-storey cross-laminated timber building, designed to mitigate changes in temperature and humidity by its mass. The drawings are kept in mylar sleeves – which allows anyone to handle them – inside plan chests with alphabetised drawers or boxes and portfolios for larger projects.

While we ask visitors for a starting point before they come, because the collection is stored in a single room, the archive building facilitates research dérives, a type of exploration that encourages an associative movement through the material. This freedom is a stark contrast to the experience of using institutional archives where, in most cases, material is requested in advance, with limited scope to deviate.

Our other activities, such as our online and physical publication projects, teaching, and exhibitions and events, all follow from experimenting with what a private organisation can do that public institutions can’t.

SP: How would Drawing Matter define the term ‘drawing’ and what are the types of drawings that Drawing Matter covers?

MP: In a way, defining drawing in an architectural context is Drawing Matter’s mission. ‘Drawing’ can be both a noun and a verb – an object and an action. We are most interested in this second, verb form. The objects in the collection are all representations of architectural thinking, generated through an active process of design, and made to communicate ideas, either to the architect themselves or to others. We do not limit the material in the collection or the material that we publish online, to any one kind of architectural representation. Alongside drawings made by hand with pencil or ink on paper, the collection contains models, collages, and photographs.

SP: Currently, Drawing Matter has 867 texts by 515 writers on 662 architects and 5807 drawings. Users can browse the data by filtering it based on category, period, and medium. Are there any specific criteria for classifying such categories? Perhaps you could also briefly introduce us to the characteristics of content per category.

MP: The categories were introduced a few years ago during a redesign of the website. As the website has grown, we have become to see it as a repository of writing to which texts on diverse subjects are added. The website is structured so that the entirety of this repository is presented on the homepage. The category, period and medium filters allow readers to modify the grid to their particular interests; the filters can be compounded (e.g. ‘Office Cultures’+ ‘Twentieth Century’ + ‘Drawing’) to narrow the field of articles, or a single filter can be used.

The repository structure affords us great freedom over what we publish and when. We don’t have thematic limitations or print deadlines, so the content of the website evolves in relation to our concerns and interests – which are often driven by collaborations with others or from experiences in the drawings archive.

We developed the ‘category’ filter after recognising that there are strong thematic strands that run through the website content. The current categories are Design Methodologies, Drawing Histories, Project & Building Histories, Drawing Techniques & Materials, Office Cultures, On Their Own Work, Commentaries, Rants & Reflections, Drawing Matter Archive, and Reviews. Together, the categories evidence our approach of balancing the stories and histories behind drawings and buildings with drawing and design theory and accounts of architectural practice.

SP: How are some particulars handled, such as the criteria and channels for collecting archives, and casting potential writers?

MP: The physical drawings collection is ever-growing. The sources of the drawings are varied, but they are generally purchased from auctions or acquired directly from architects. When acquiring new drawings, we are always thinking about what a drawing might add to the material that we already have – can it be put in dialogue with other drawings? Does it fill a gap in the story of architectural practice?

The website is run in a similar way: we aim to add texts that expand our understanding of drawing and complement, or challenge, the texts we have published to date. Most of the texts we publish are generated through Drawing Matter’s wider activities – collaborations with architects, researchers, educators, and students – but we also invite proposals from writers.

In rather the same way, we offer open access to the collection catalogue, and organise it in a way that never claims the description of any drawing to be definitive or final.

SP: The projects run by Drawing Matter are largely divided into Editorial & Series, Education, and Exhibition. In what direction do they each cover the subject of drawing? How are they related, and how do they complement one another?

MP: We have many different projects happening simultaneously. Over the last two years, we have been working on a number of serial articles in which writers have been able to develop extended discussions. These include Pan Scroll Zoom, edited by Fabrizio Gallanti, which surveyed how online teaching during the pandemic affected the role of drawing in teaching studios; Drawing as Metaphor, a series of essays by artist Deanna Petherbridge on her recent drawings; and Drawing Powers by Fernando Poeiras, an exploration of how collections of drawings can help us to understand the different uses of drawing within architectural design projects. We also have several new series in development, including podcasts commissioned in collaboration with the Architecture Foundation.

The other project subheadings represent the scope of Drawing Matter’s activities beyond the editorial content published on the website, including our Summer School for sixteen to eighteen-year-old students, and exhibition projects, which are usually based on material in the Drawing Matter collection and curated in collaboration with other organisations.

SP: In these projects, it appears that the ability of editors and editing are critical factors. What are your thoughts on editorship?

MP: Our priority is to publish articles that are thoughtful and clearly expressed. There are seven members of the editorial team, all of us part-time, and we all work together on the commissioning and editing of articles. In addition, we also work with external editors on specific projects, such as Mark Dorrian, who is the Editor-in-Chief of our recently launched academic journal, DMJournal – Architecture and Representation.

In addition to the editors, there are three more members of the team who work on cataloguing the drawings collection.

SP: Projects often result in the publication of books. What do you consider the meaning or value of a separate book, as opposed to a website (online media)?

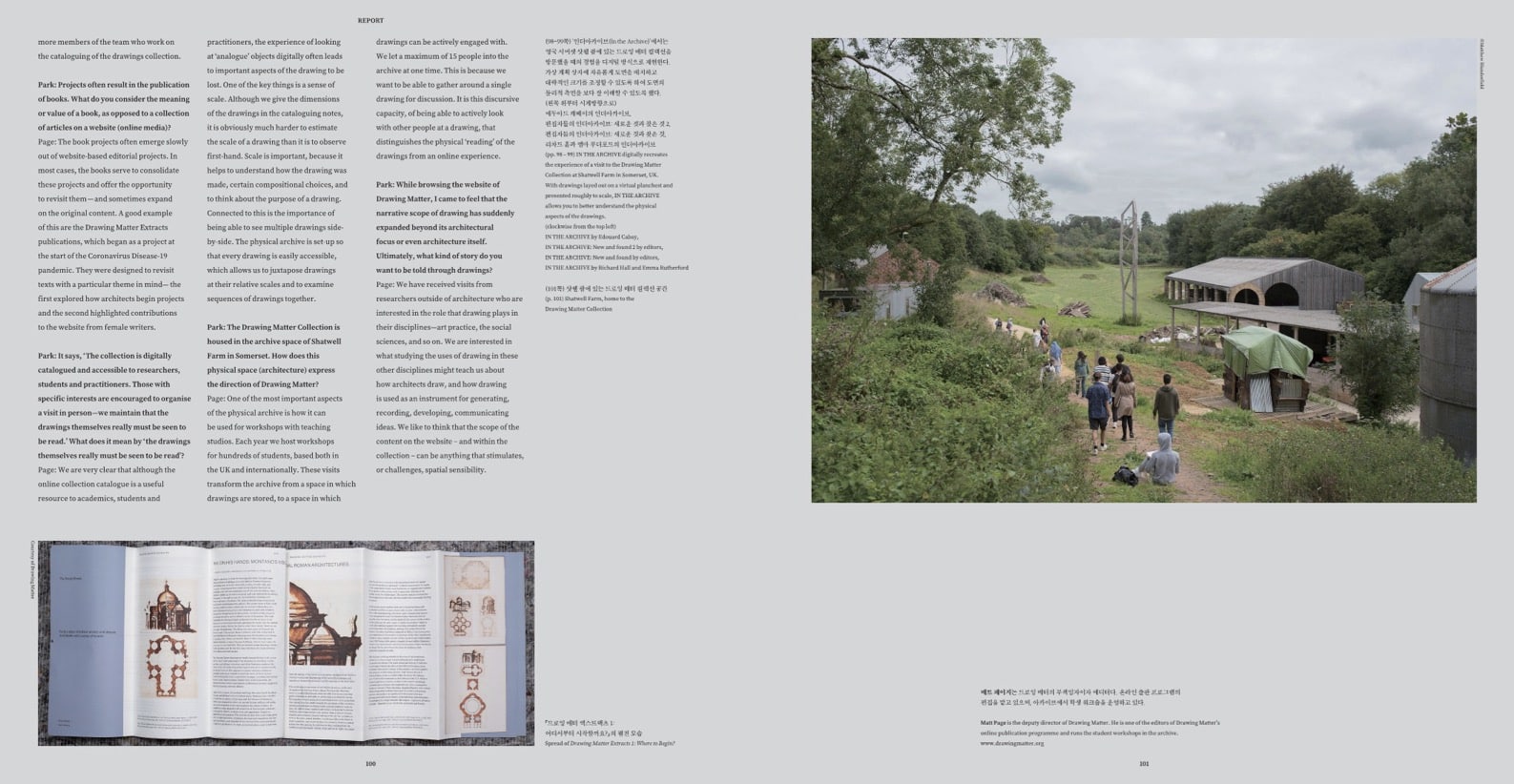

MP: The book projects often emerge slowly out of website-based editorial projects. In most cases, the books serve to consolidate these projects and offer the opportunity to revisit them – and sometimes expand on the original content. A good example of this is Drawing Matter Extracts, which began as a project at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. They were designed to revisit texts with a particular theme in mind – the first issue explored how architects begin projects and the second issue highlighted contributions to the website from female writers.

SP: It says, ‘The collection is digitally catalogued and accessible to researchers, students and practitioners. Those with specific interests are encouraged to organise a visit in person – we maintain that the drawings themselves really must be seen to be read.’ What do you mean by ‘the drawings themselves really must be seen to be read’?

MP: We are very clear that although the online collection catalogue is a useful resource to academics, students and practitioners, the experience of looking at ‘analogue’ objects digitally often leads to important aspects of the drawing being lost. One of the key things is a sense of scale. Although we give the dimensions of the drawings in the cataloguing notes, it is obviously much harder to estimate the scale of a drawing than it is to observe first-hand. Scale is important because it helps to understand how the drawing was made, compositional choices, and purpose.

Connected to this is the importance of being able to see multiple drawings side-by-side. The physical archive is set up so that every drawing is easily accessible, which allows us to juxtapose drawings at their relative scales and examine sequences of drawings together.

SP: The collection of Drawing Matter is housed in the archive space of Shatwell Farm in Somerset. How does this physical space (architecture) express the direction of Drawing Matter?

MP: One of the most important aspects of the physical archive is how it can be used for workshops with teaching studios. Each year we host workshops for hundreds of students, based both in the UK and internationally. These visits transform the archive from a space in which drawings are stored to a space in which drawings can be actively engaged with.

We let a maximum of fifteen people into the archive at one time. This is because we want to be able to gather around a single drawing for discussion. It is this discursive capacity, of being able to actively look with other people at a drawing, that distinguishes the physical ‘reading’ of the drawings from an online experience.

SP: While browsing the website of Drawing Matter, I felt that the narrative scope of drawing has suddenly expanded beyond an architectural attachment, an architectural essential, or even architecture itself. Ultimately, what kind of story would you like to tell us through drawings?

MP: We have received visits from researchers outside of architecture who are interested in the role that drawing plays in their disciplines – art practice, the social sciences, etc. We are interested in what studying the uses of drawing in these other disciplines might teach us about how architects draw, and how drawing is used as an instrument for generating, recording, developing, and communicating ideas. We like to think that the scope of the content on the website and within the collection can be anything that stimulates, or challenges, spatial sensibility.

SP: How are the finances and budgets managed to maintain the continuous operation of Drawing Matter?

MP: The educational and publishing programmes that Drawing Matter run is funded by The Drawing Matter Trust, a charity set up for the purpose. Other projects, like our annual summer school, are generously funded by architects and architectural practices, with the support of our partners at Kingston School of Art and Hauser and Wirth Somerset.