Luc Deleu & T.O.P. OFFICE: Future Plans, 1970–2020 (2021) – Review

Future Plans is one of those titles with double and ambiguous meanings. Not exactly as twofold as the most famous ‘The Architecture of the City’ but maybe leaving us equally free to choose. Is the term ‘future’ to be considered as an adjective or a subject? Does this book thus gather plans for a possible future, or is it illustrating the future itself in progress? Both options are probable with regard to the declared goals of this small publication (in size, rather than in content).

In the introduction, the editors reveal that it is not a catalogue raisonné, and that the 63 critiqued and illustrated works by T.O.P. OFFICE have been chosen according to the criterion of ‘being or provoking a “future plan”’. So, according to the editors, the book could be read as a ‘toolbox’ to elaborate a strategy to deal with what is coming upon us and to reveal how these ‘future plans’ can ‘inspire the designers, architects, urban planners, ecologists, lawyers, administrators and policy makers of today and tomorrow’. On the other hand, while looking at these projects, one could suspect that the future was indeed planning itself ahead of us, and the title might also hint at the somehow premonitory stories told by T.O.P. OFFICE. Indeed, Luc Deleu once famously said: ‘I never quite understood why you would first have to wait for a question before formulating an architectural answer’, he himself naming his approach ‘post-futurism’.

The result of impressive editorial work by Peter Swinnen – a former intern of T.O.P. OFFICE in the 90s – and his office partner Anne Judong, the book was put together on the occasion of the homonymous exhibition at De Singel in 2021 and provides a broad overview of Deleu’s and his partners’ legacy. There was probably no better moment to publish the group’s work, which seems like a manuel de l’architecte engagé: civil disobedience, reluctance towards the act of building, political engagement, ecological conscience, unsolicited proposals, a wish to transcend the immobility of architecture, a fascination for a now longed-for mobility, operation at the crossroads of art and architecture, etc.

The book as an object definitely blurs conventions: its small size and thickness – similar to a livre de poche – could encourage the curious buyer to expect a single, longer text – an essay by a single author, for example, or a story of Luc Deleu’s adventures (such as one of his many meditative sailing trips) that read like a novel, probably scarcely illustrated, if at all. To the contrary, this small publication is a miniature monograph, full of drawings and carefully selected images organised chronologically. T.O.P. OFFICE’s own project descriptions alternate with short interpretations by not less than 44 different authors. This constellation of opinions leaves the reader with a fragmented view of the oeuvre, which is in itself multiple and wide-reaching. These collective endeavours are not a new trend in contemporary media and exhibitions.

Allow me here a parenthesis on the recent fashion of the group review, the ultimate tool of contemporary architectural debate. An established pattern for art exhibitions and for architecture biennales, the phenomenon of the group show has been proliferating in recent years indicating a strong trend towards manifold architectural discourse. San Rocco magazine collected plural opinions on a set topic. OFFICE KGDVS’ monograph provided external reviews of their own projects, asking the current scene to critically debate their architecture. Many exhibitions have taken a similar path, including Alternative Histories organised by Drawing Matter, which asked a very large number of practices to each reinterpret an archival drawing in model form. International re-drawings of Bramante’s tempietto, collages of legendary urban plans, gatherings of animal sketches by architects, or a collective re-writing of Aldo Rossi’s Architecture of the City (for which I take the blame, by the way) nourish this world of ‘classroom’ exercises. These constellations often leave the reader slightly frustrated. They open up a very broad array of opinions and possibilities but refrain from a sustained narrative. In other words, maybe this format should become less pervasive, and should not substitute all other genres of architectural discussion.

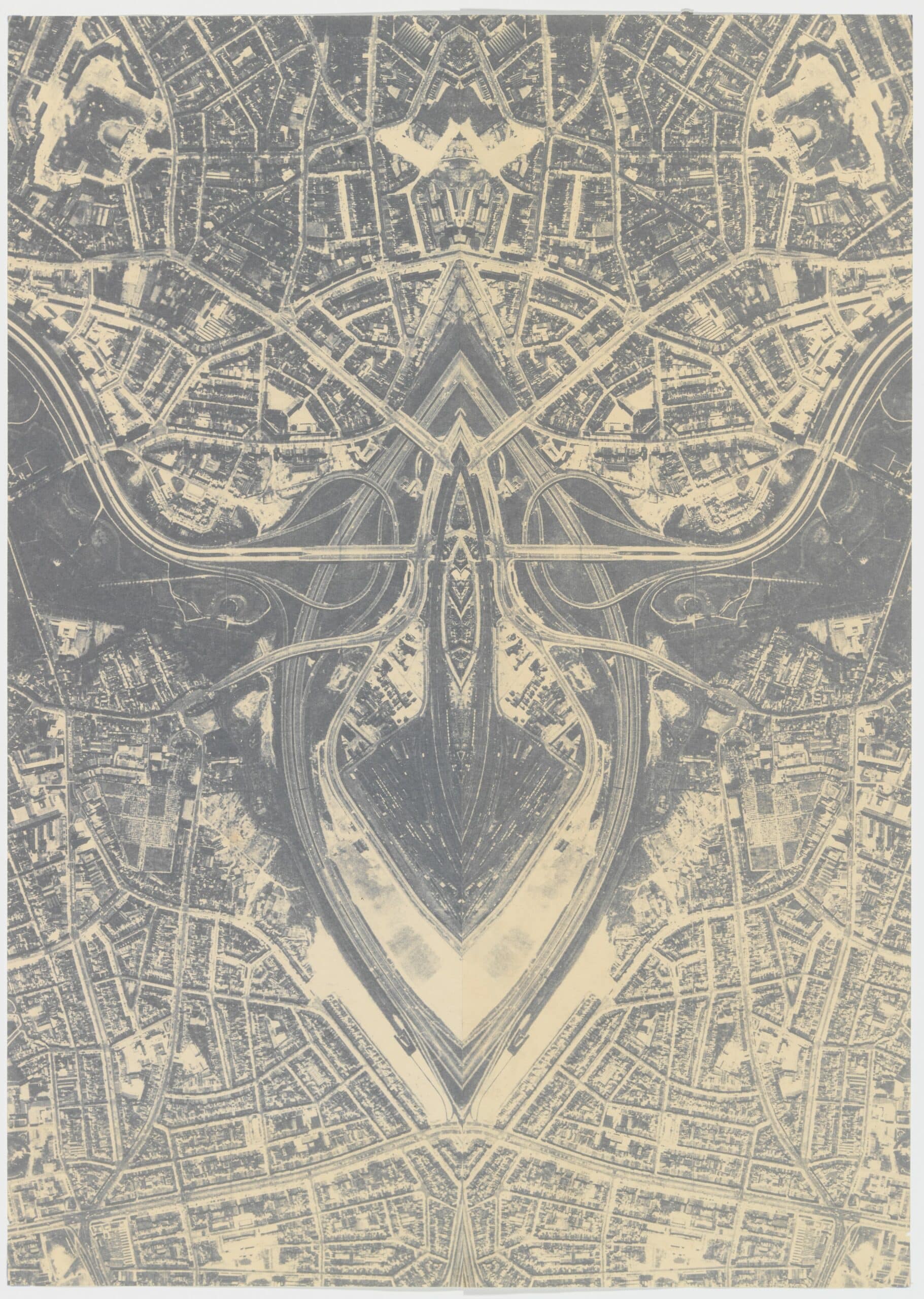

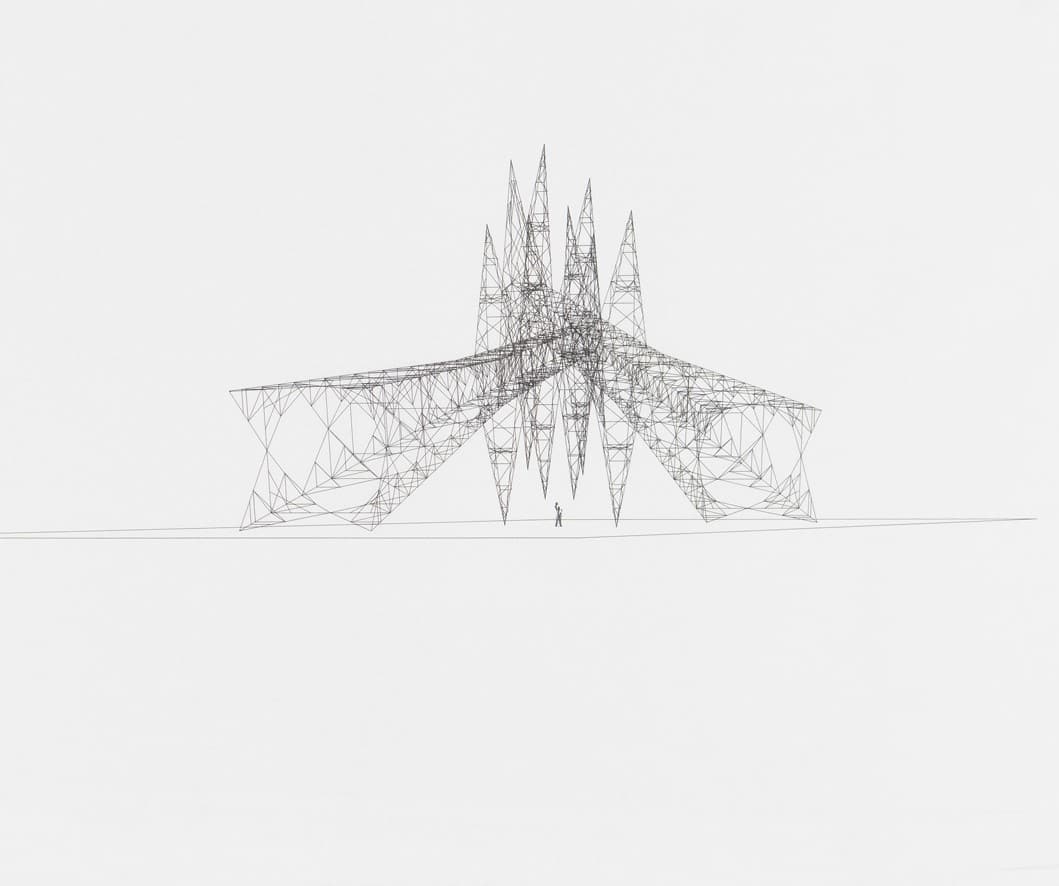

But, in this case the collective exercise corresponds to the nature of T.O.P. OFFICE’s work. Deleu’s manifesto-minded projects, his social engagement and his provocations give the impression that he himself sees his work as a kind of architectural Speakers’ Corner. Architecture is thus used as a means rather than as a final goal, which materialises in projects in motion, such as a campus on a boat. Leaving aside Deleu’s artistic practice, the book intentionally describes only two built architectural interventions. These are the famous house for Panamarenko and the interventions made to the Furka Pass dependence, the residency in the Swiss mountains established by Deleu’s gallerist, Marc Hostettler. Room thus remains for the utopian infrastructural projects, but also for their critical ‘gaze focused on people, the planet and the future’ impregnated with an unexpected realism, but which often turns into the dead-ends of utopia on reading that they intentionally ‘keep their activity independent of normative politics, economics or sociology.’

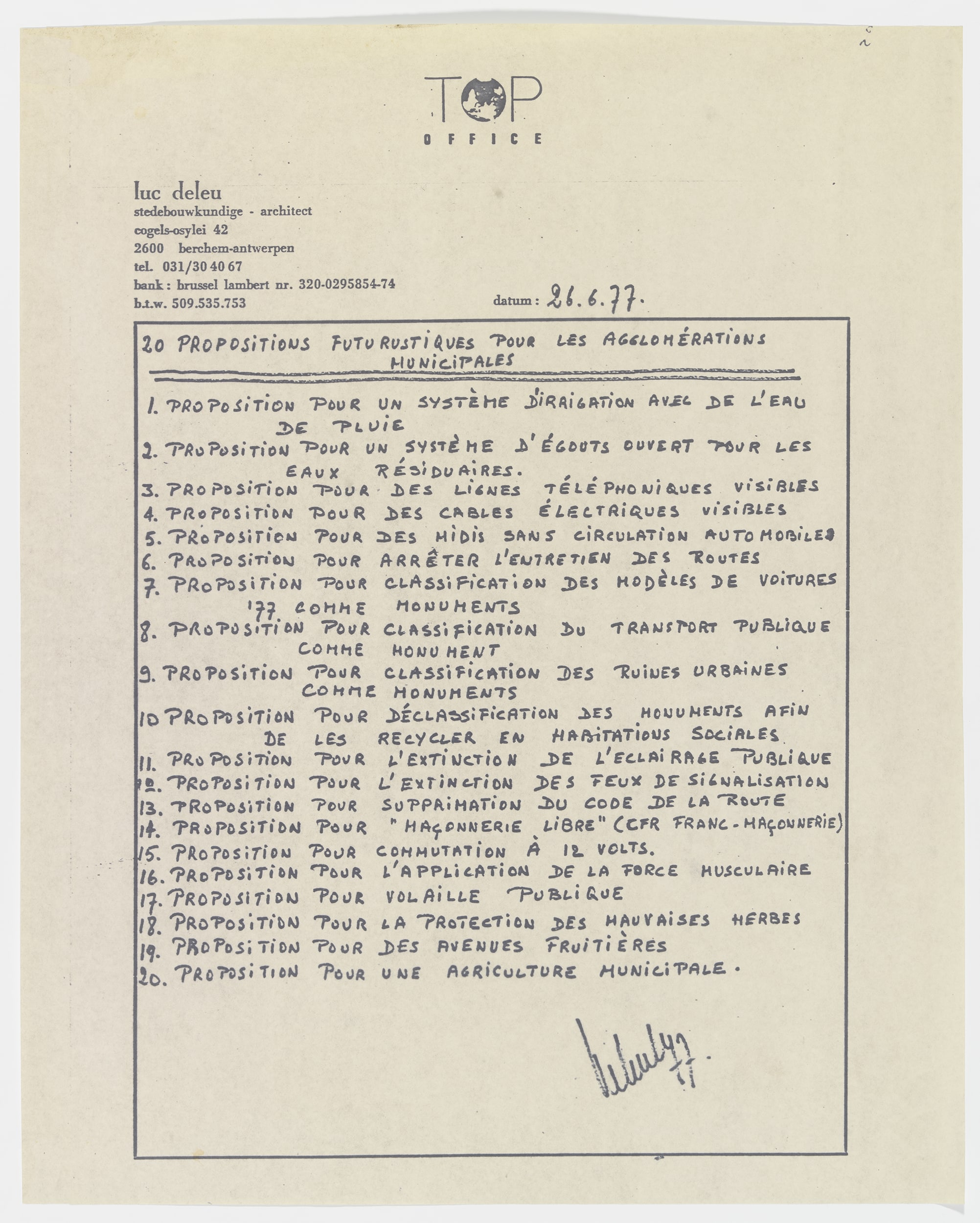

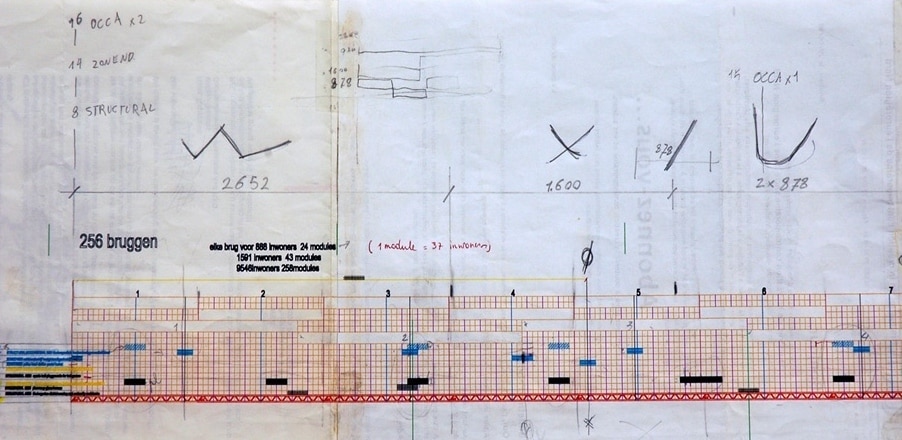

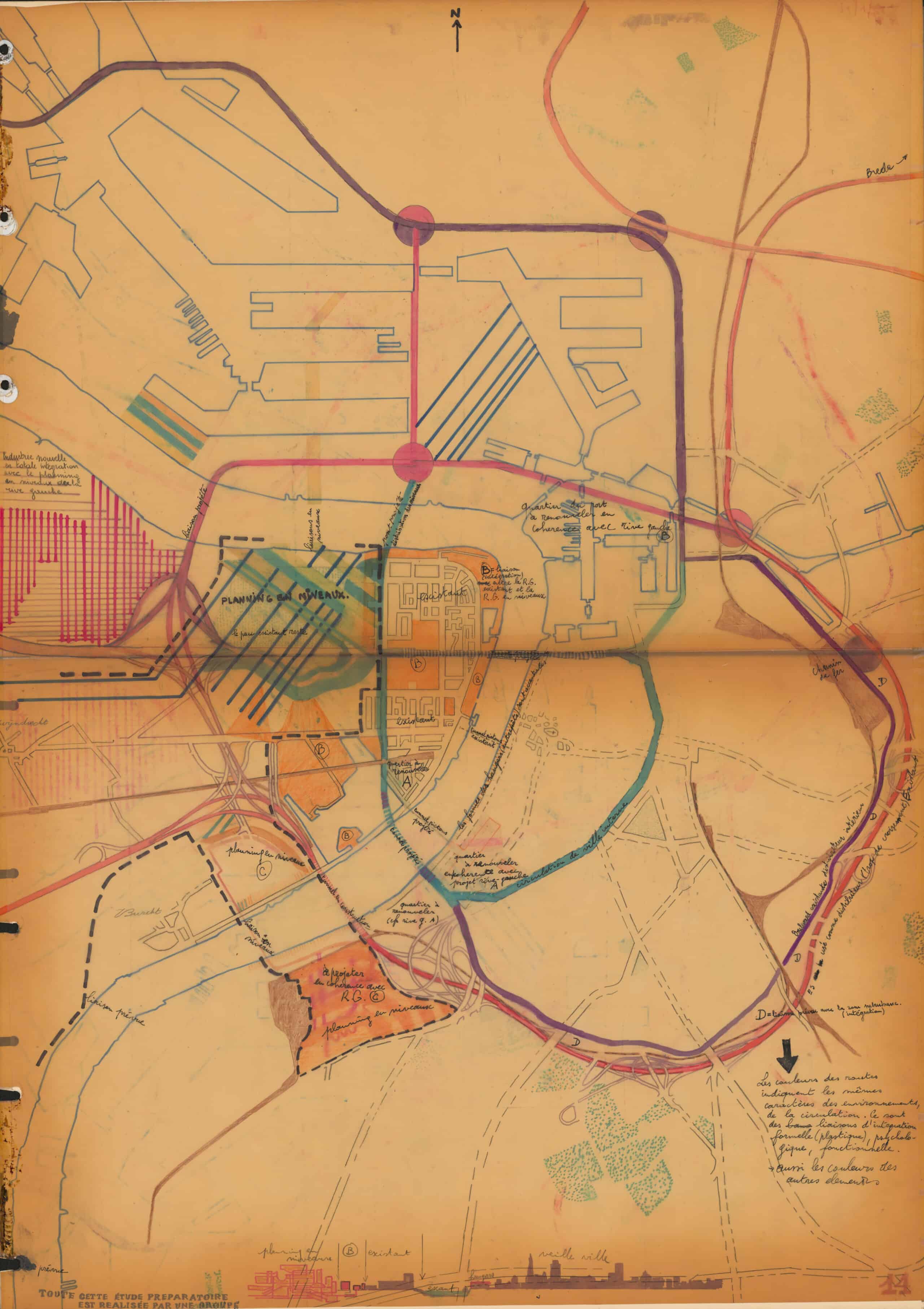

In Future Plans, Deleu’s theoretical treatises and paradigmatic statements – such as his 1985 pamphlet Towards Re-use, which couldn’t sound more contemporary – take an important role in transmitting his radical messages. Many are printed as facsimiles, generously allowing the reader to see the smallest corrections undertaken by hand to a lecture just before giving it. Reading some of the guests’ essays would benefit from good insider knowledge of Belgian urban design history, Antwerp’s particularly, but they are often counteracted by poetic or witty interpretations of other projects. For example, André Loeckx gives a precise explanation of T.O.P. OFFICE’s Ring Road project while drawing upon Rossi’s theory of monuments and recalling the lesser-known 1933 Linkeroever planning in Antwerp by Le Corbusier. Lieven de Cauter reappraises T.O.P. OFFICE’s ecologic Proposals and debates their prophetic statements while praising their capacity to ‘reverse the order of things’. He also dares to mention the slight frustration felt by Deleu upon seeing his proposals disappearing within art institutions, when he sees them as gravely earnest. Recurrent use of absolute geometrical order within T.O.P.’s work is poetically suggested by Bart Verschaffelt’s essay, in which he states that ‘the inhuman regularity that architecture smuggles into the world solves nothing, but is the consolation of architecture’.

But what is Deleu’s consolation for his non-built architecture? It is difficult to buy Deleu’s ‘farewell to architecture’ when seeing the care put into his graphic production: precise axonometric drawings, assured graphic design, artistically framed polaroids, even his step into the twenty-first century with digital drawings is highly controlled and bears witness to a careful search for a personal aesthetic. Going through the book, one regrets not getting a few more insights into movements both contemporary and inspirational to T.O.P. OFFICE that might have taken similar utopian paths and made equally visionary statements (since many of these groups have been less durable than T.O.P. OFFICE). Instead, Le Corbusier is omnipresent and Deleu’s unconditional love for him is openly declared. Another question remains unanswered: who is T.O.P. OFFICE? The attribution of individual or shared authorship is blurred, their internal relationships are only vaguely mentioned, and maybe too much is left to the interpretation of the reader. Internal dynamics, authorship, shared aesthetic language and the role of Laurette Gillemot – one more wife of – remain in the shadows. T.O.P. OFFICE itself could be considered as one of T.O.P. OFFICE’s most successful, real and surprisingly long-lasting projects. A palpable one, which could also be seen as a precedent to future partnerships.

Luc Deleu & T.O.P. OFFICE: Future Plans, 1970–2020 is published by the Flanders Architecture Institute; copies can be purchased here. The exhibition of Future Plans, 1970–2020 is curated by Peter Swinnen and Anne Judong and jointly produced by the Flanders Architecture Institute and De Singel. The exhibition runs until 26 September 2021 (more info).

Victoria Easton is an architect and associate at Christ & Gantenbein with whom she also teaches and leads research and exhibition programmes at the Department of Architecture, ETH Zurich.