Neglected Dimensions: Rough Sketches for Public Space

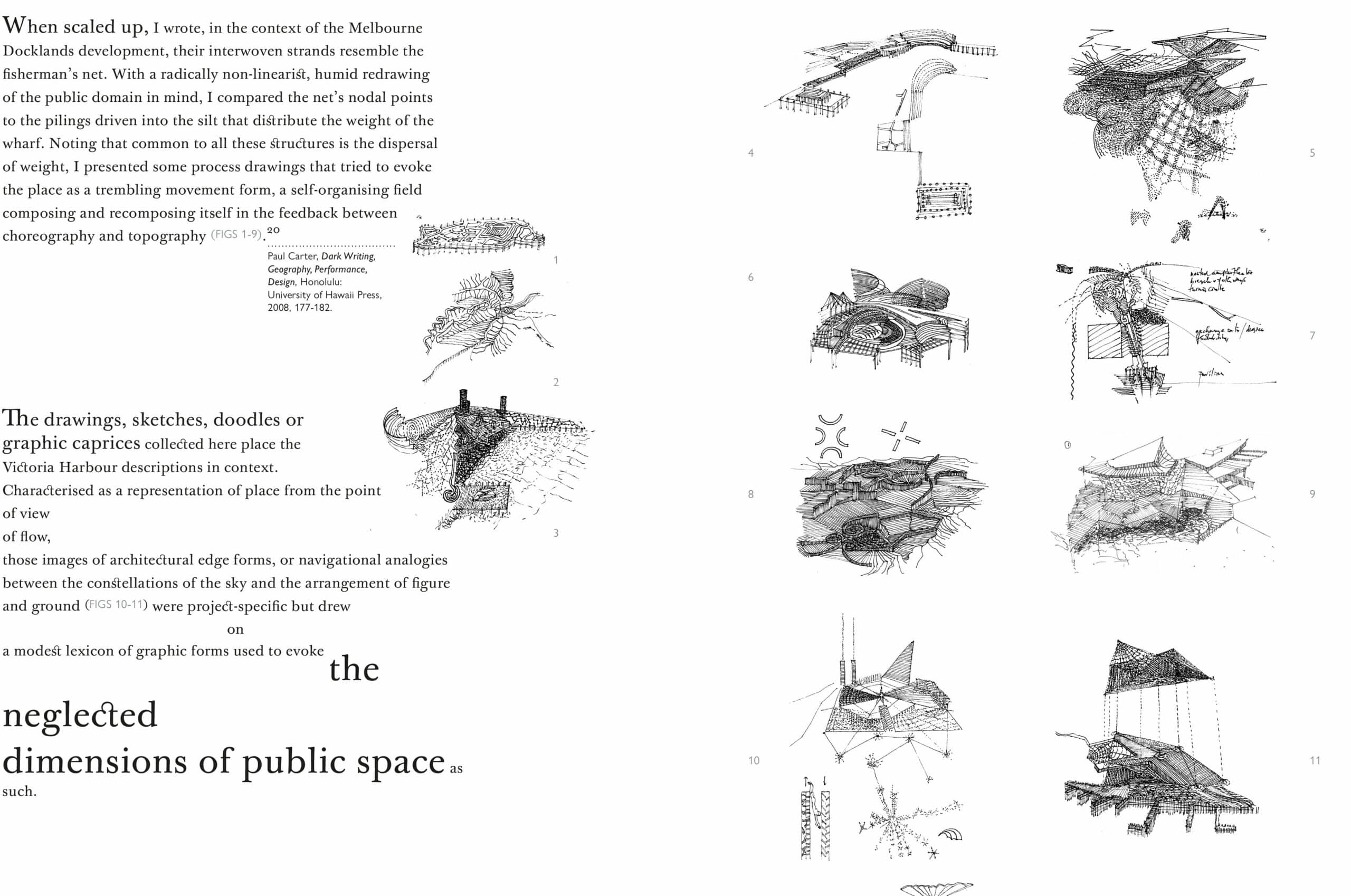

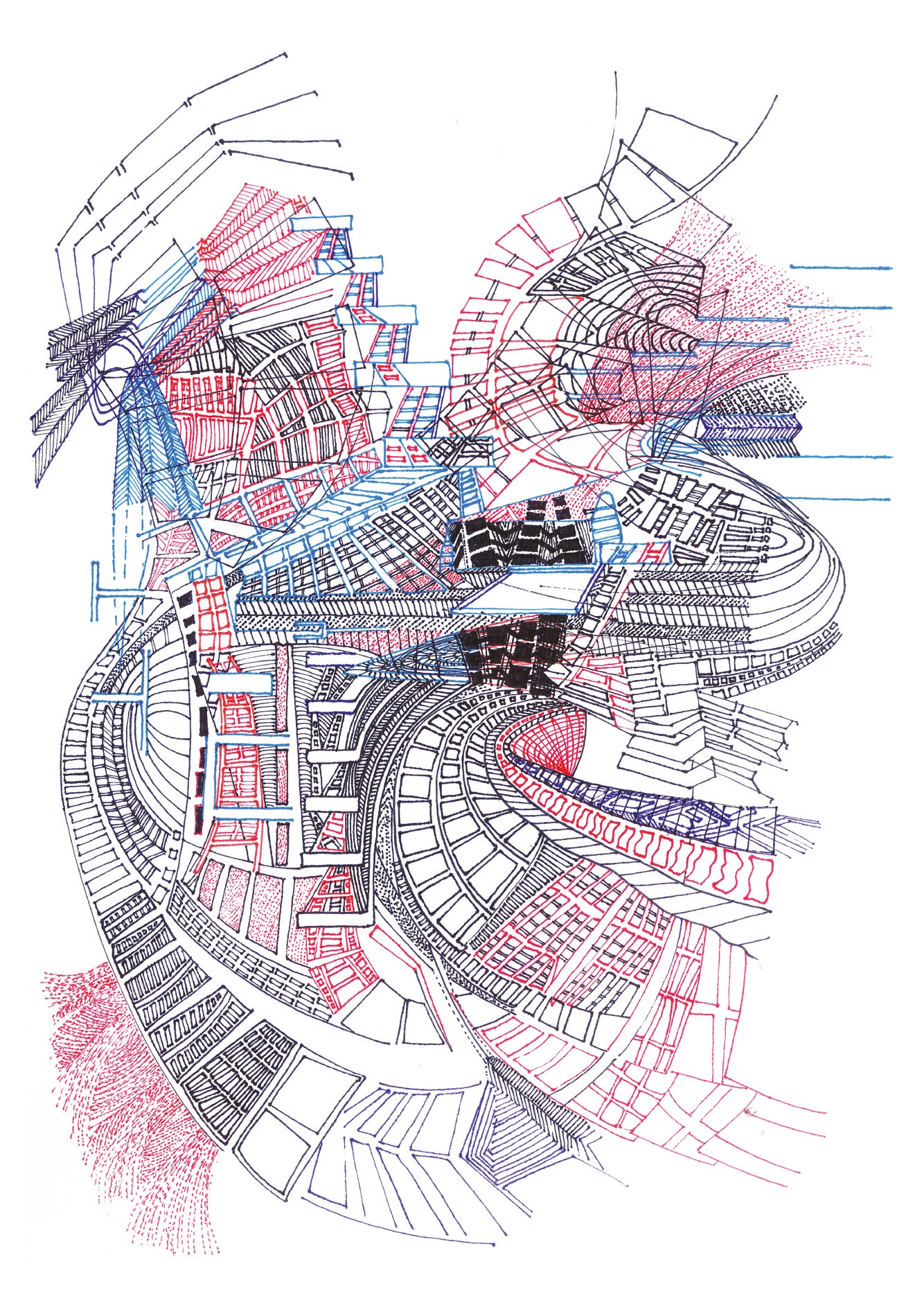

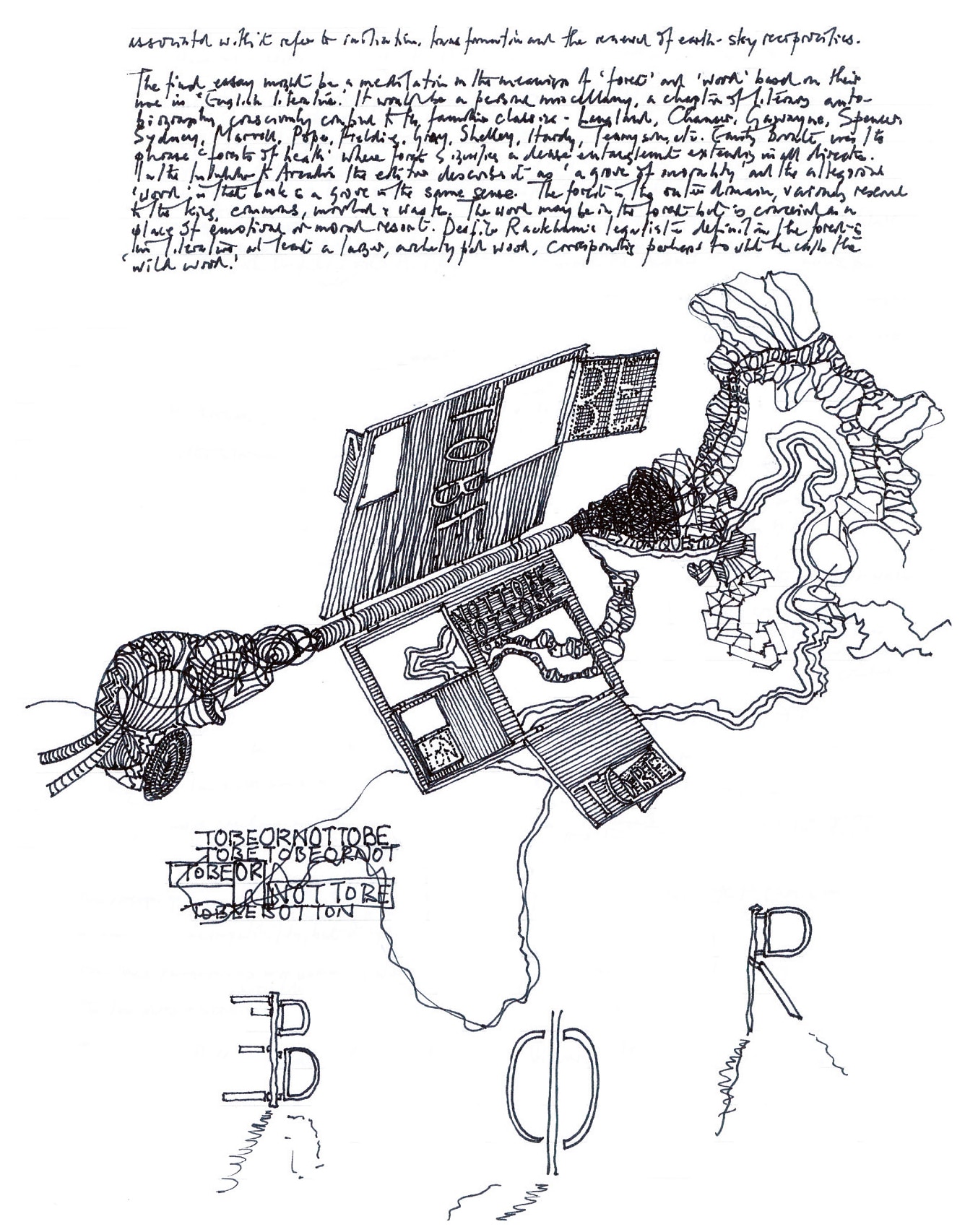

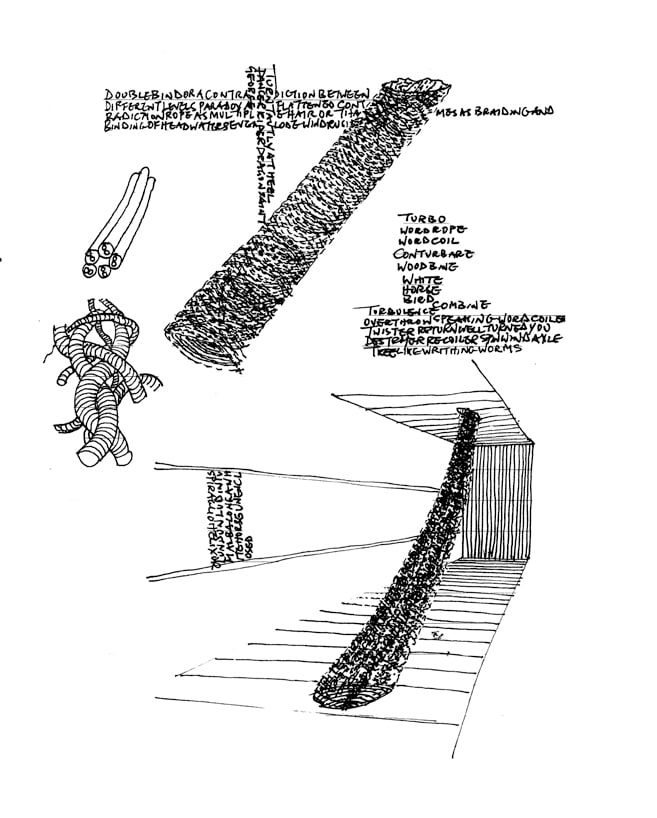

Neglected Dimensions: Rough Sketches for Public Space by Paul Carter mediates between graphic form and text, movement-tracking, and place-making to delineate the interstices of public space: what escapes its formal description and what falls outside official design. The book responds to pertinent concerns about the interface between the designers of public space and its users—past, present, and future—but also to the ever-unresolved relationship between writing and drawing in design practice. It is beautifully designed by John Warwicker to highlight this negotiation. The text is carefully choreographed on the book’s pages, with key words and phrases popping out in larger font, occasionally intercepted by notebook records: sketches, drawings, cartoons, and doodles of realised and unrealised projects. The middle section of the book, from page 78 to page 125, is dedicated to the ‘plates,’ drawings that take a full page each, allowing the reader to examine them closely. Text also appears within the sketches, sometimes in the form of note-keeping or annotation, and others transforming to patterns that intersect with the space of the drawing itself. Occasionally, blue-grey pages with large font text interfere and read as mini manifestos, among others: ‘public space was not given’, ‘public space does not exist. It is given—or, where withheld, wrested from those who deny it with the threat of violence’, ‘the enigma of public space emerges when we try to define its scale’, and ‘a paradox lies at the heart of urban design’, setting up the pace of the book.[1]

Many years ago, via Repressed Spaces: The Poetics of Agoraphobia, Carter pointed out to me a beautiful account of public space by Hannah Arendt:

‘The public realm, as the common world, gathers us together and yet prevents our falling over each other, so to speak. What makes mass society so difficult to bear is not the number of people involved, or at least not primarily, but the fact that the world between them has lost its power to gather them together, to relate and separate them. The weirdness of this situation resembles a spiritualistic séance where a number of people gathered around a table might suddenly, through some magic trick, see the table vanish from their midst, so that two persons sitting opposite each other were no longer separated but also would be entirely unrelated to each other by anything tangible.’[2]

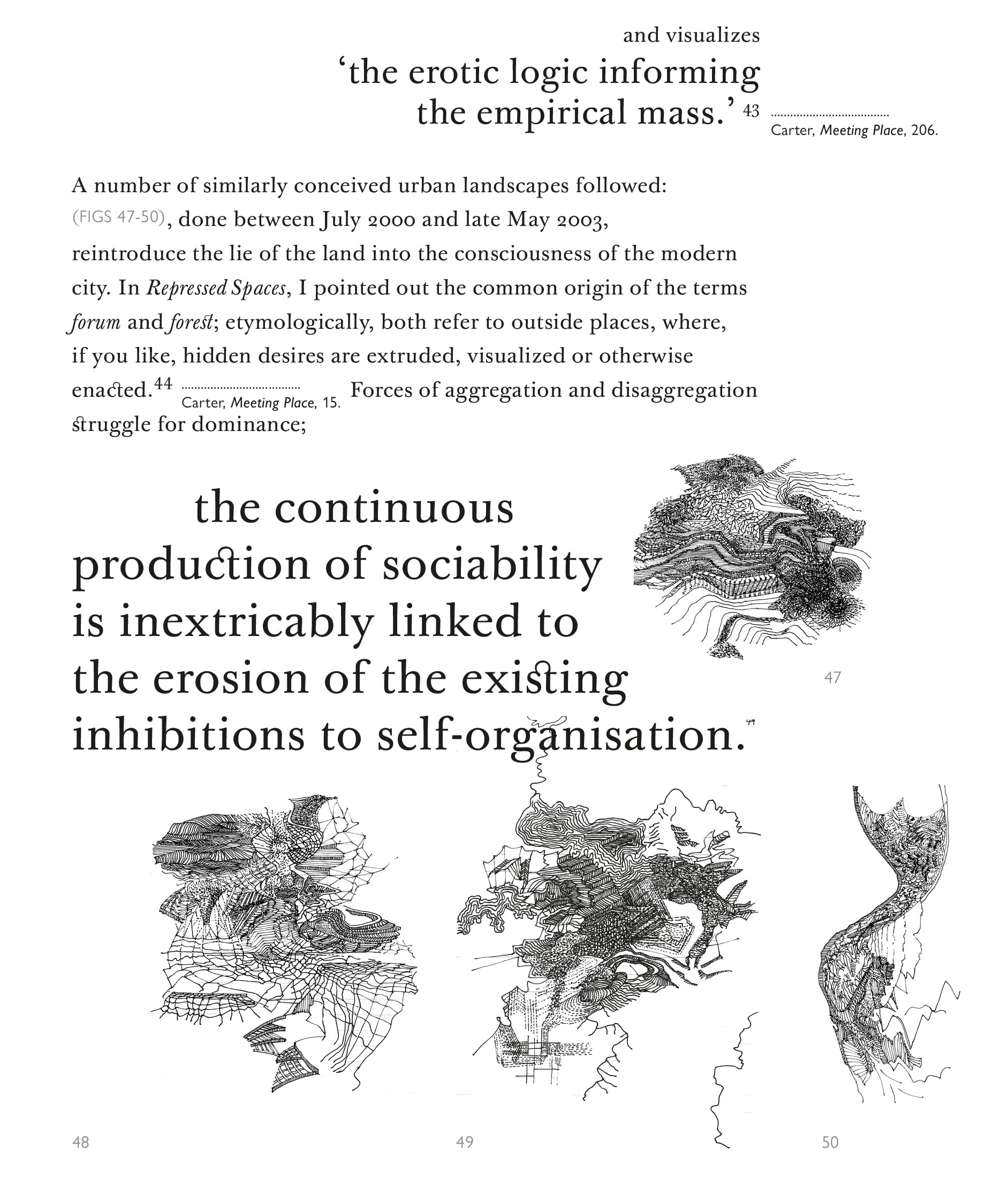

Arendt describes the public realm as an oscillation between touch and intactness, action and reservation, moving forward and self-limitation, and compares the incapacity of the space to bring the people together to a spiritualistic séance, where people are seemingly gathered around a table, yet the table has disappeared, leaving them completely disassociated and thus missing anything physical that could hold them together. Alongside, Carter asked: how is it possible to make concrete what has become abstract? Neglected Dimensions returns to this apparent void and attempts to make sense of the empty space for action, also raising the question as to whether it is truly empty. It formulates a statement against the abstraction of public space and towards its conceptualisation as a site-specific social, environmental, and political becoming. The book sets out for the performative production of public space, to question the role of scale in its definition, to understand storytelling and movement forming as place-making, to delve into the in-between space of sketches, to discuss the design relationship between writing and drawing, and to return to the question of public space and its power to gather and disperse people.

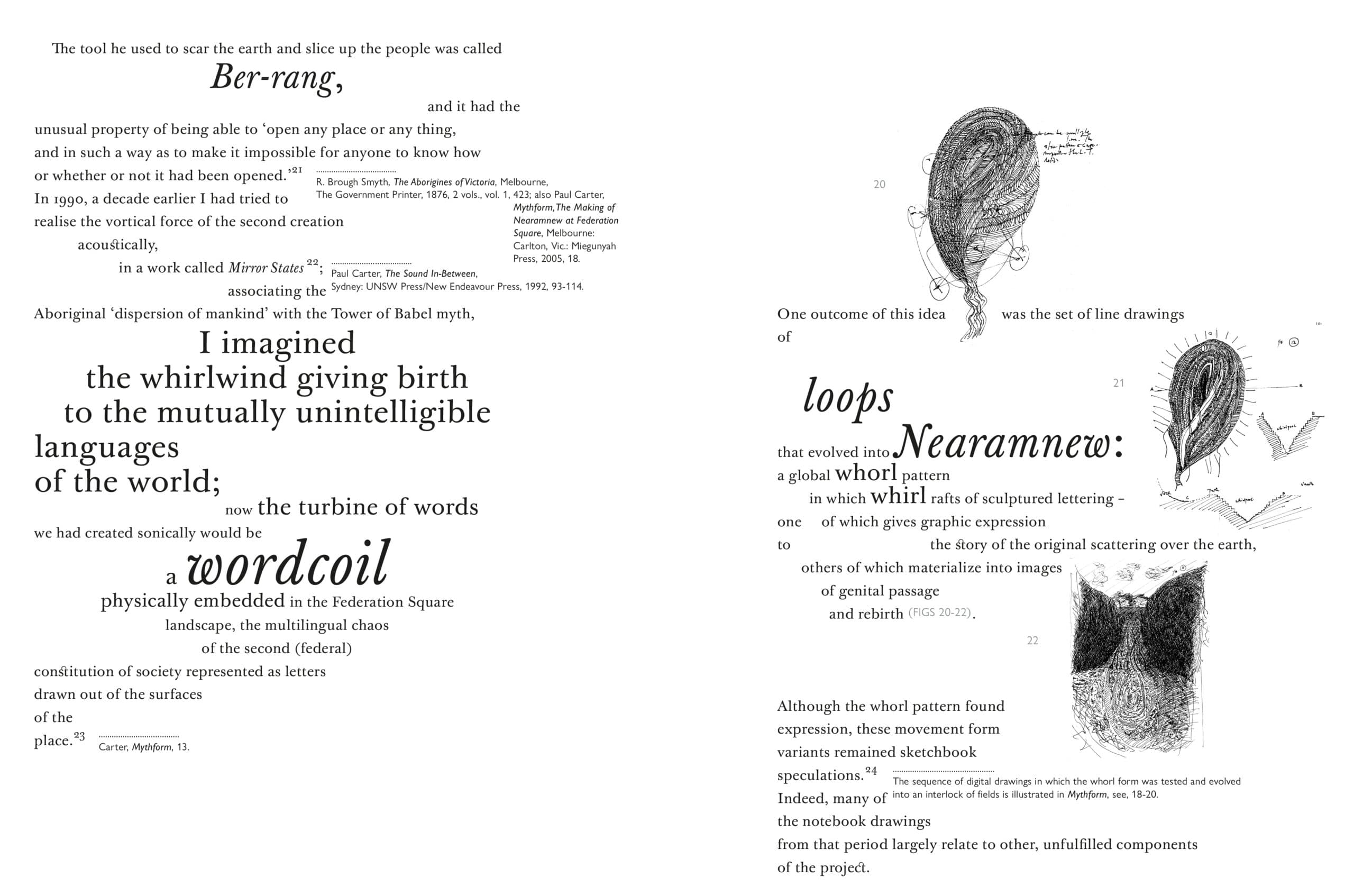

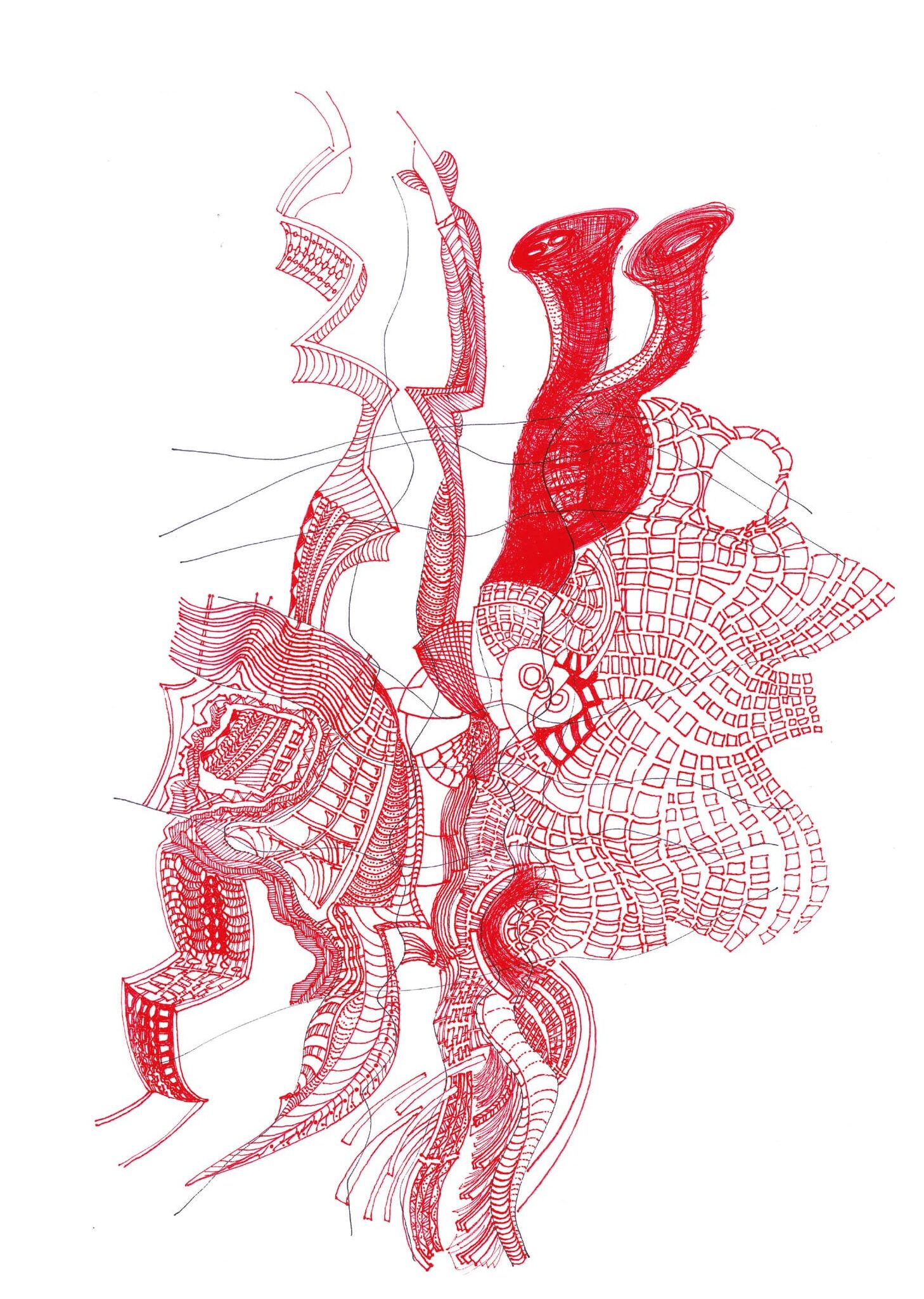

The text guides the reader from concepts to projects to histories, and to sketches and drawings. The Ber-rang, a mythological object that has shaped Nearamnew (public art, Federation Square, Melbourne, in collaboration with Lab architecture studio, 1998–2002), becomes a recurrent trope to facilitate such transitions. According to the Aboriginal story of creation of the place where Melbourne currently stands, the creator used the tool to cut the earth—forming rivers, mountains, and valleys—as well as people, whom he scattered all over the earth with great power. The Ber-rang could scar and slice the ground in a way that no one would be able to tell whether or how something had been cut open; this scoring and moulding of the earth at once and as if from within is understood here as drawing and making place at the same time and in a process of self-becoming. We see the Ber-rang playing out in projects as well as in the sketches that have instigated them: cutting the ground open to expose the words of the stories that has created it; re-marking territories to restore pre-colonial conditions and to reverse colonial operations; reconfiguring relationships between landforms and waterforms; uniting the place-making forces with the trails they leave behind; and holding together the natural elements and the constructions that compose a place. The purpose of the sketches here is neither representational nor illustrative; instead, they outline processes and trajectories, and they spatialise histories. Sometimes they test formal compositions, and at other times they describe atmospheres, bringing together spaces and designed objects.

In their indefinite form, the sketches bring about the question of scale: if scale is a matter of viewpoint, asks Carter, then what happens when we want to consider all points of view? Does the loss of scale break down all the established hierarchies of public space causing a loss of control? A series of sketches featuring ladders presents the antidote to this scalelessness. We see them wrapping around spaces, setting up scenes, transforming into lattices, and punctuating landscapes. The ladder becomes a measuring device for spaces and mediates between the human scale and the extent of public space. There are other thematic sections too: a group of sketches concentrates on wordcoils, indicating spaces in the making and on the move. The persistence of the process of becoming and forms of movement in the book, as well as the constant shifts from writing to drawing, propose interesting transitions from the narrative to the diagrammatic and a new practice of form-making that is conceptual and compositional at the same time. This is the role of the sketch here: it indicates a meeting point, the intermediate space between thinking, writing, and drawing. It is a ‘thought picture,’ a visualisation of a concept in anticipation of a designed place.

And then there is the social purpose of such sketches: they facilitate conversations on place-making, they gather stories of places, and they map trajectories and potential relationships between places. They prompt debates, and they invite interpretations of ideas in the making. They speculate on meeting places, and, in the meanwhile, they become themselves the meeting points between the designer and the public. In this way, storytelling and notation, linear and non-linear descriptions, blend into complex networks: ‘there is, after all, a natural resemblance between place-making stories and places made after their stories.’[3] The multiplicity of linework in the sketches and the fact that they represent less of an established object and more of a set of possibilities allows for multiple temporalities as well as patterns of movement to take part in this complexity and to prompt the emergence of a place.

The above processes and the emphasis on storytelling in place-making contradict the formal standing of urban design. The designed space for action and political co-existence cannot be void, empty of voices, people, and stories, argues Carter. If spaces are shaped after their stories, then we need to come up with methods to capture and make sense of them, away from the designer’s single perspective as well as from the command of the quantitative data collection. Most importantly, we need to come up with ways to translate such stories and interconnections to patterns and fields that can uncover hidden or overlooked spaces. Translations are never straightforward and unmediated, of course, but this is what is involved in the process of meaning-making: as stories and dialogues and patterns superpose on each other and on drawings, diagrams, sketches, and topographies, exciting spaces can emerge.

This brings us back to the relationship between drawing and writing and how the two are brought together by design rather than by discourse. In the sketches presented in the book and in the projects that underpin them, calligraphy blends with choreography to produce public inscriptions and to materialise meanings. The mythical function of Ber-rang returns here: in the same way that the Ber-rang operates between cutting through spaces and moulding them, writing becomes entangled with sculpting. Literally and metaphorically, writing opens up and turns inside out so that places reveal words and, conversely, wordings shape places. Then writing/drawing places imply a double movement: the gesture of the hand drawing-and-writing places and the movement of people are coordinated in a mutual performance, gathering and dispersing at once, keeping together and breaking apart, in a ‘sociability in a flux.’ [4] Plate 33 reflects on this fragile condition between separation and connection and takes me back to Arendt’s mediation of public space between action and reservation.

In the last section of the book and returning to the ‘neglected dimensions’ of public space, Carter turns to sports crowds to dissolve the distance between the observer and the player/actor, and to propose a new relationship between vision and tactility. The player and the spectator in a football game, he argues, engage with each other in a condition of joined awareness, which weaves together the time and space of the game. Similarly, the sketches in the book compress space—pre-existing, as it currently stands, and in its becoming—and time—past, present, and future—to produce a ‘dramaturgy of public space.’[5] This liberates seeing from the fixity of the single point of view and replaces it back into the crowd (the public) to allow for multiple ways of seeing and projecting oneself into the space, as well as for new shared experiences and manifestations. Then the performativity of the public space is subject to the crowd and the event, and how they act upon each other, at times working together and others separately. Ultimately, the sketches are open-ended and indeterminate to allow for such multiple possible meetings and interactions. They propose a public space that evolves and renews itself with time and the people involved; a space that resists both universal planning and the idealisation of a democratic space for all—and a space that is replete with stories to be told.

Notes

- Paul Carter, Neglected Dimensions: Rough Sketches for Public Space (New York: Actar Publishers, 2024), 13, 17–18, 67–68, 147.

- Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 52–53 and Paul Carter, Repressed Spaces: The Poetics of Agoraphobia (London: Reaktion Books, 2002), 189.

- Paul Carter, Neglected Dimensions: Rough Sketches for Public Space, 142.

- Ibid., 185.

- Ibid., 188.

*

Aikaterini (Katerina) Antonopoulou, Dr, is a Lecturer in Architectural Design and the Director of the Master of Architecture at the Liverpool School of Architecture. Her research focuses on mediated representations of the urban and the politics of the image.