Pan Scroll Zoom 14: Alfredo Thiermann

This is the fourteenth in a series of texts edited by Fabrizio Gallanti on the challenges in the new world of online architectural teaching and, particularly, on the changing role of drawings in presentations and reviews. In this episode, Alfredo Thiermann reflects on his experience of drawing during a pandemic, in both his teaching at Harvard and his practice ThiermannCruz (thiermanncruz.com).

Coming to Terms with Drawing

I will always remember it as a special one, that day in March 2020 when I was convinced that the world had conspired both in favour and against me. Against, because I immediately realised that I – and everyone else around me – was condemned to existentially commit to drawing while teaching and that teaching architecture had finally become synonymous with the digital nightmare of drawing exclusively on a screen. I have fundamentally avoided that activity throughout my entire architectural life. I have always cared more about construction, about the materiality of things, about how to put one thing next to the other, to the point that I literally built – 1:1 – my final project at the university in order to become a professional architect in Chile. Partially true and partially joking, I did that just to avoid producing that many drawings. And that is basically what I used to teach: our studios were always full of large models, and all the drawings we produced were targeted at teaching and interrogating that mysterious intuition that the basic act of constructing something always requires. My curiosity as an architect was mostly about the role of materials – old or new – within this increasingly digitised world. But the new biological, political, technological, and social circumstances had turned the act of hammering a nail or plying a musical chord either a criminal or a totally irrelevant act. At first glimpse, we were all condemned to the flatness of the screen, apparently erasing the material component of my original curiosity. The universe had conspired against us. I was convinced. That very same day, I also thought that the world had conspired in my favour. I was teaching in another country and therefore I was forced to go back home, to the people I love. I began to like the idea of turning my rather chaotic domestic environment into something halfway between a classroom and a broadcasting studio. Personal affects aside, it was only then that I realised that I had already been doing that for a while. Since my small practice is in Chile, I live in Berlin, and I was teaching in the United States, I was all too used to screen-sharing my life and my work. I was already used to be patient in virtual meetings, and I was also used to be attentive to the visual and sonic aesthetics of my own background. My telephone was already full of constructor’s and fabricator’s contact numbers, and communicating with them through drawing with my finger over images on the screen was a recurrent habitus of my life as an architect. In a way, my practice prepared me for this. I decided to share my interest in things and matter with the students while thinking how to make matter work on and with the screen. I just had to come to terms with drawing.

Reaction 1

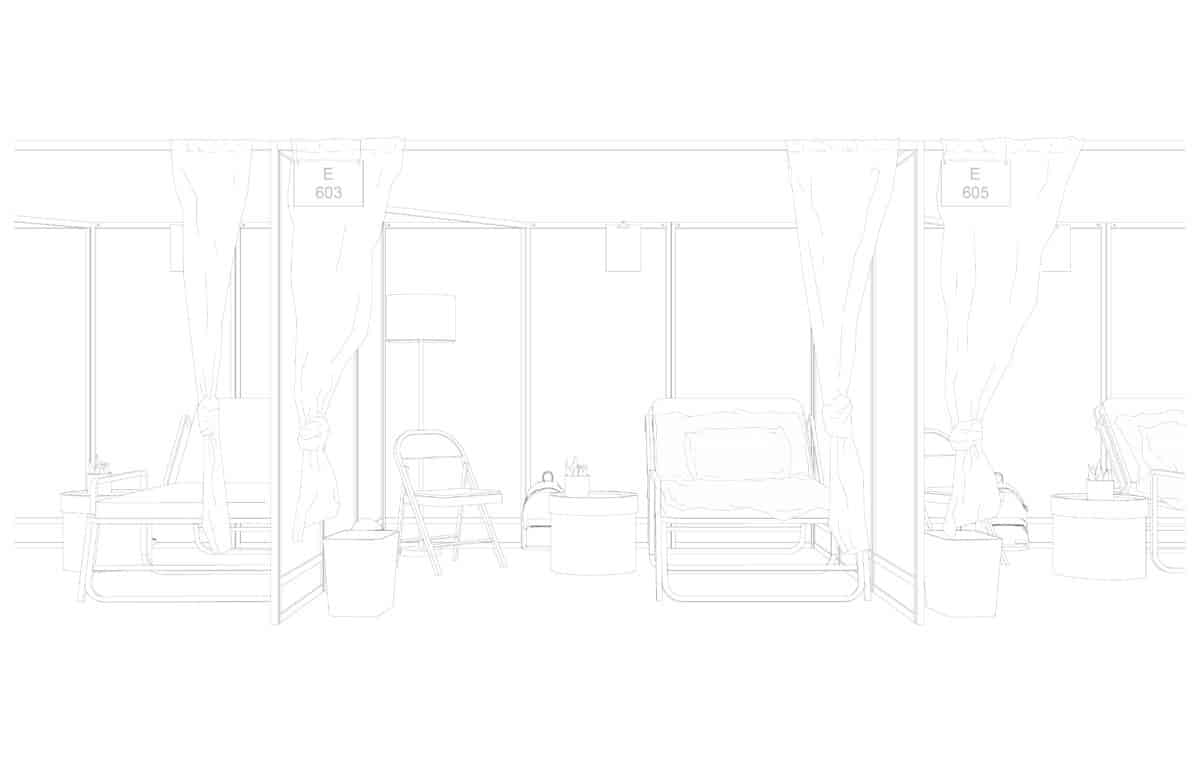

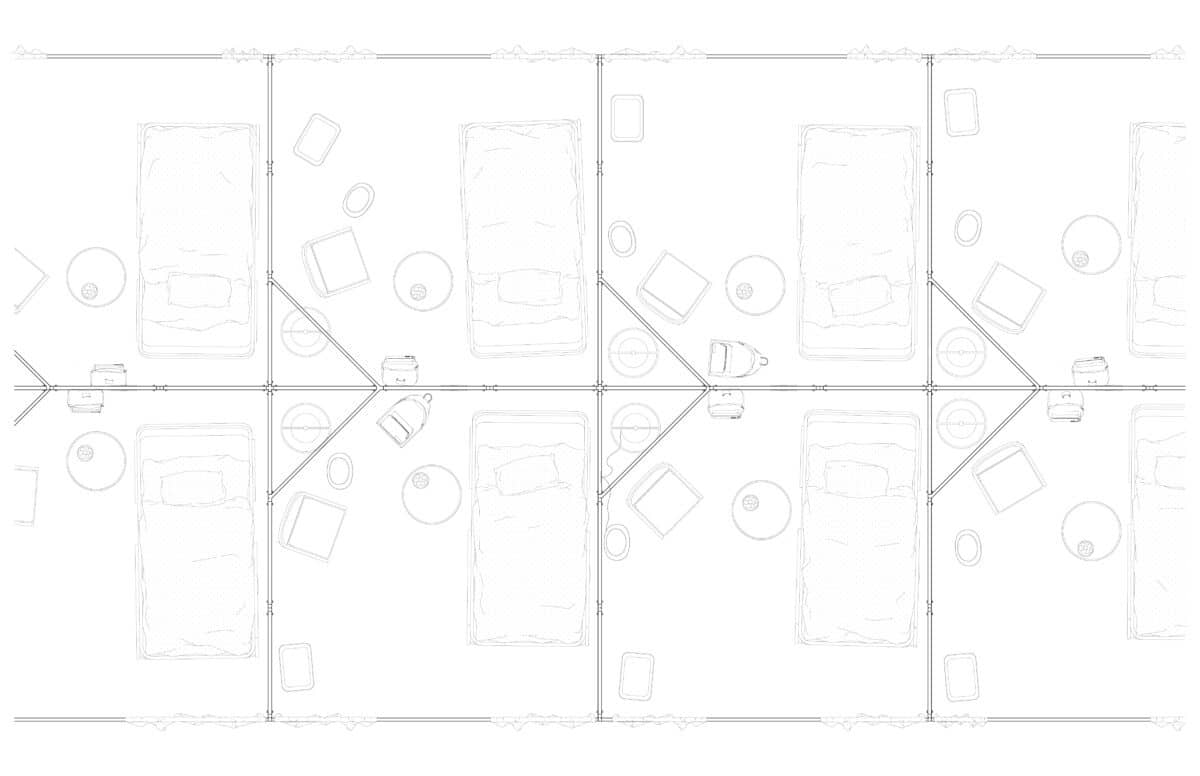

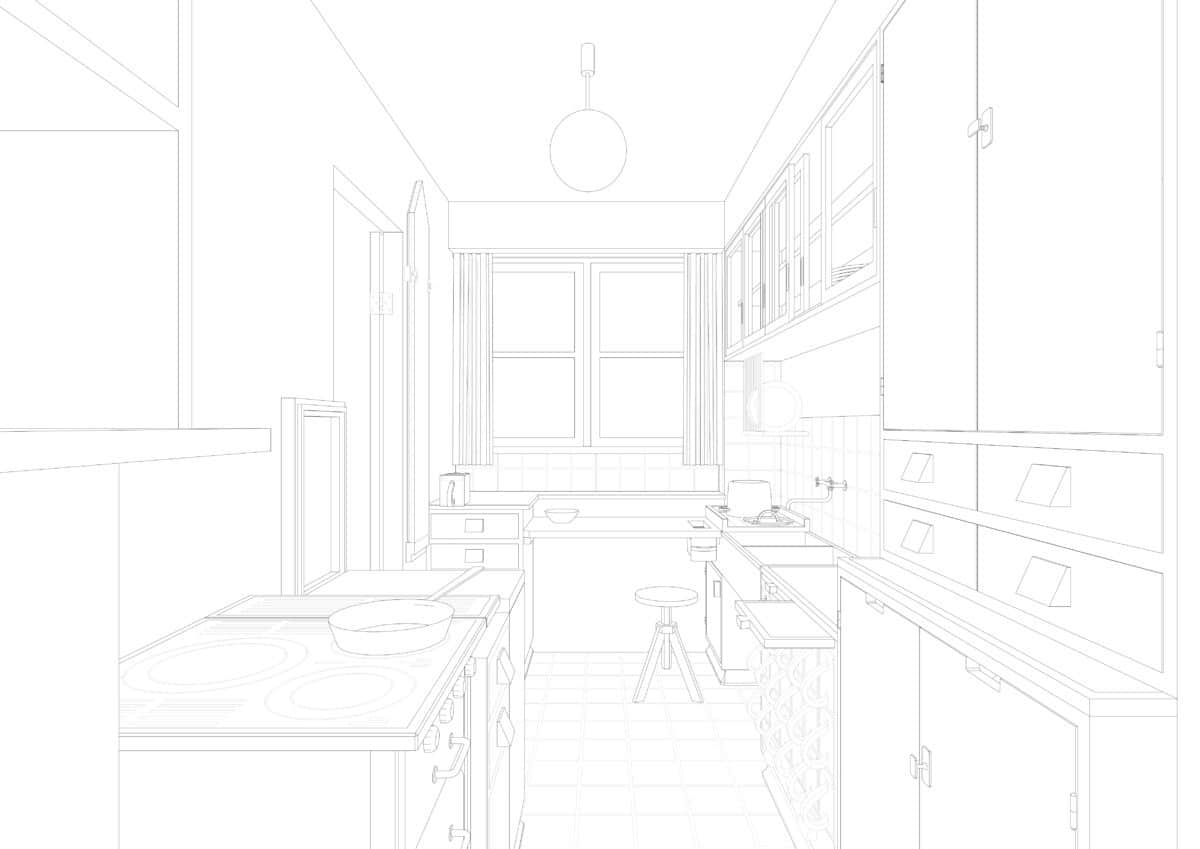

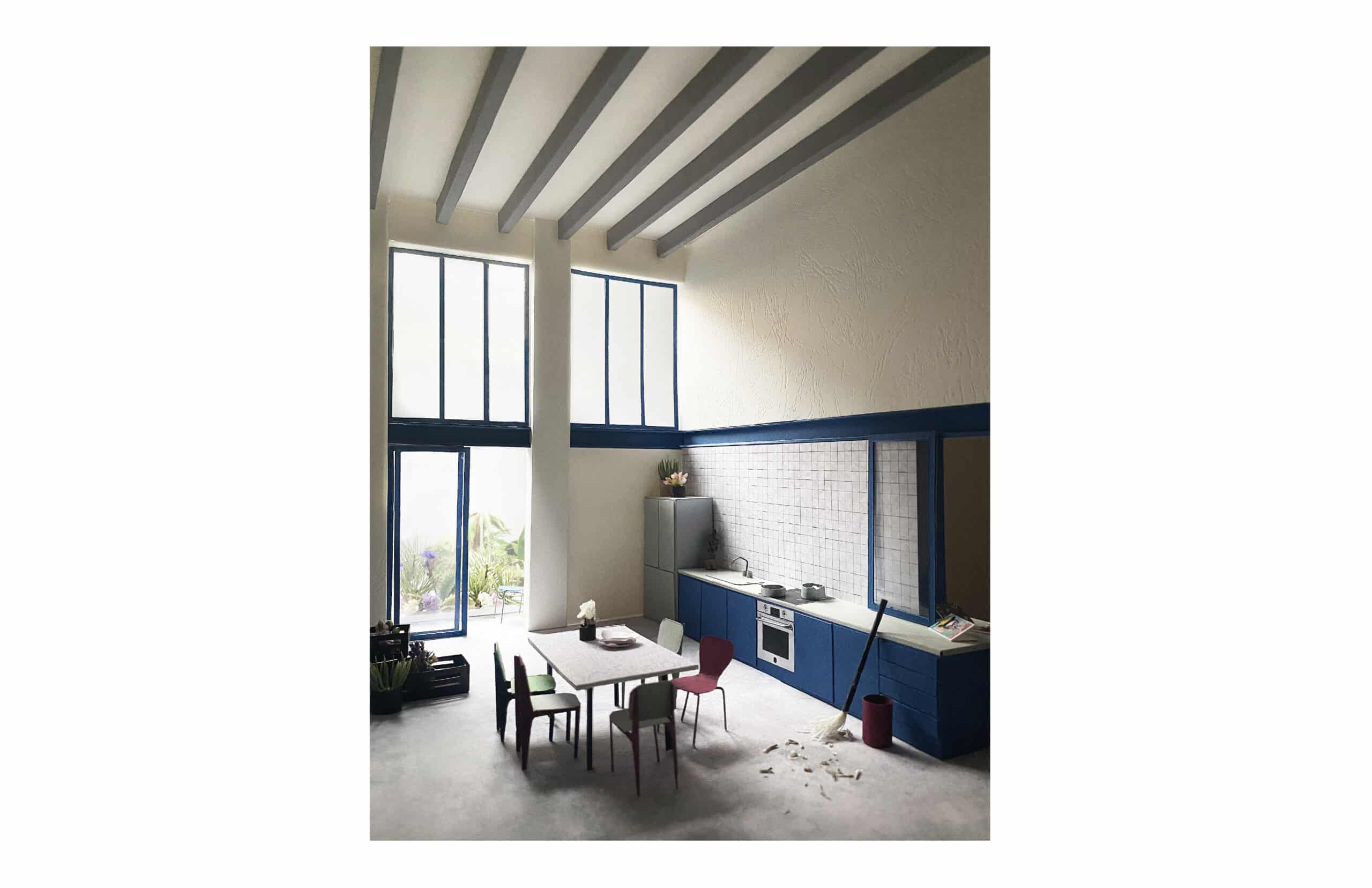

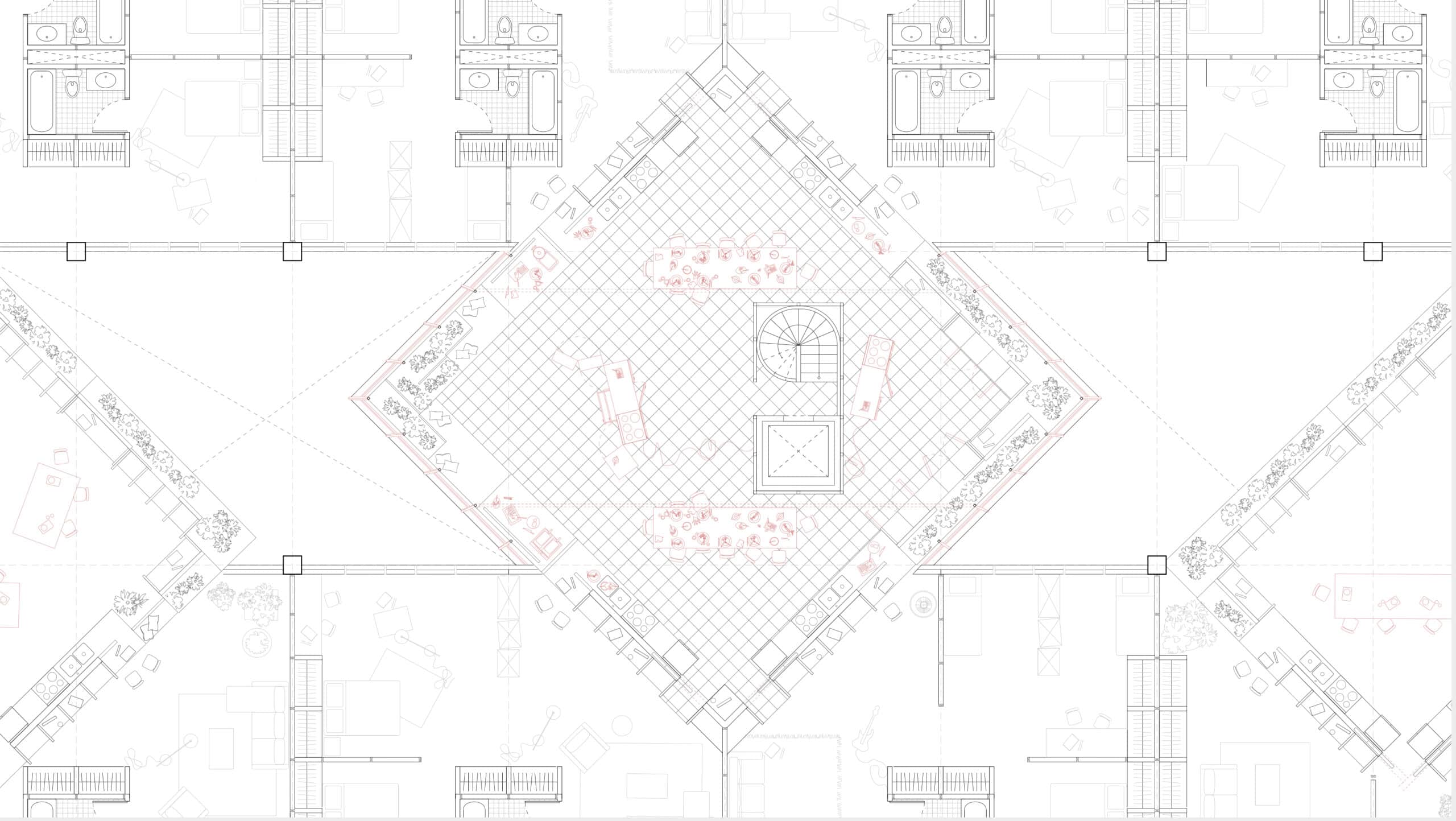

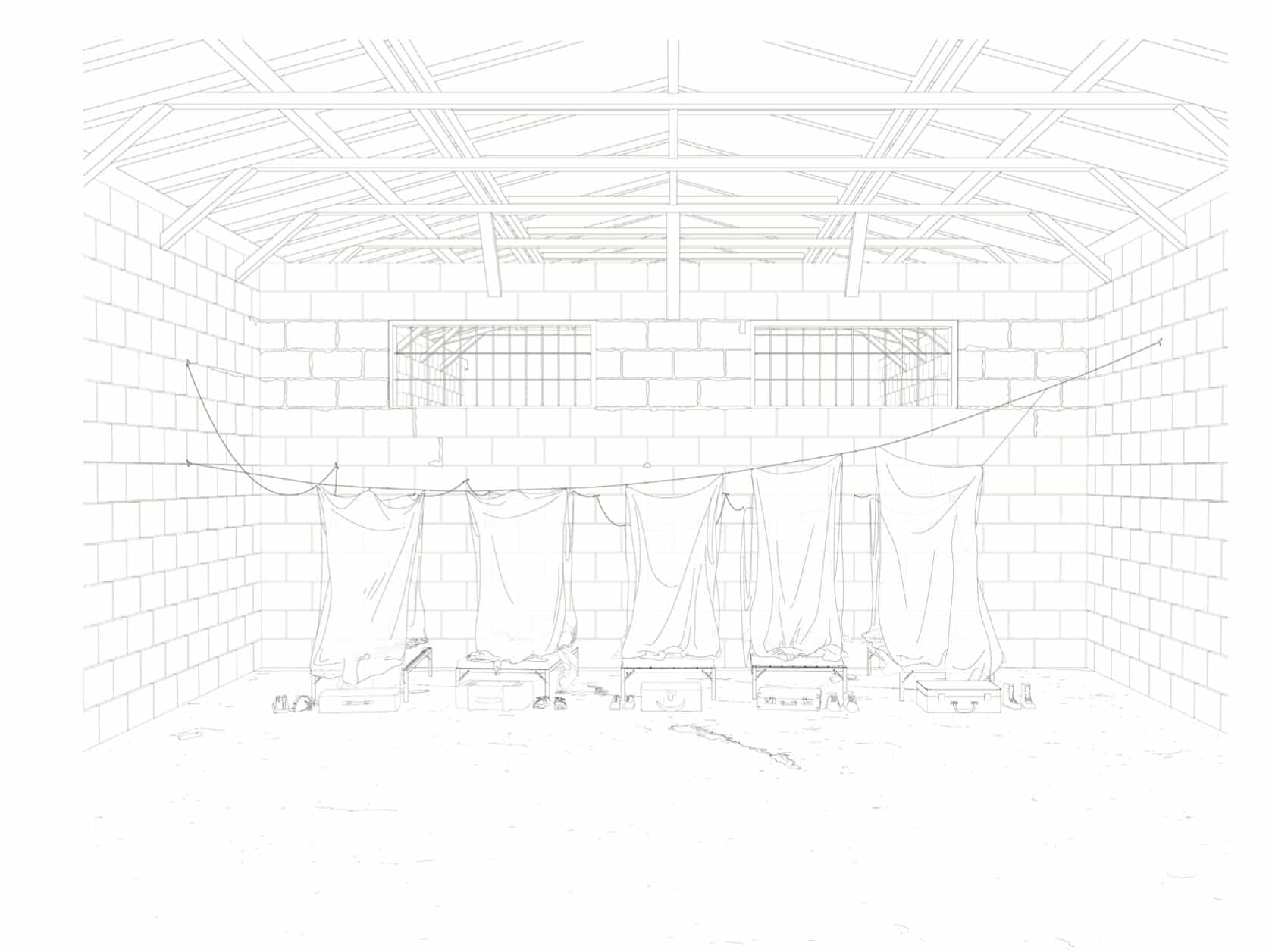

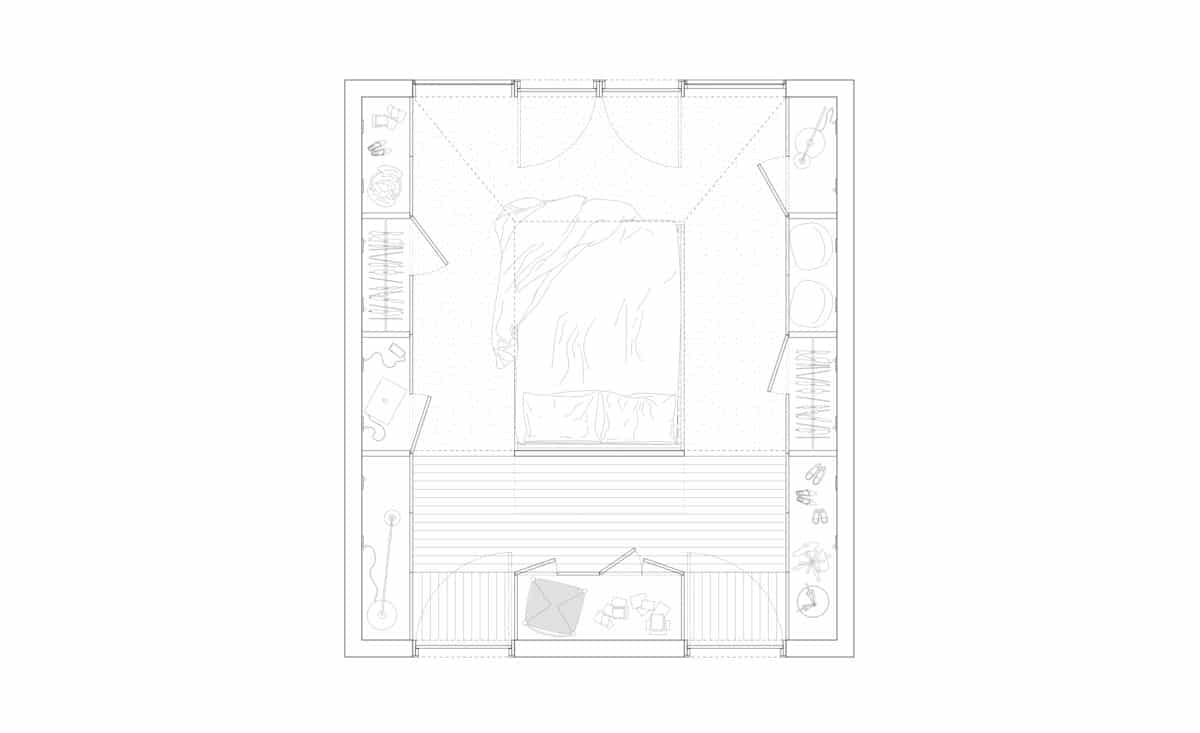

As soon as this new form of communication became the new water for us fish, my students and I agreed that what was happening outside of the screen was far more relevant and interesting than the actual act of talking at each other mediated by a grid of faces. Almost as part of a collective therapy, my students began to document what they had around them through drawing. Attention obviously lingered towards the interior, and we began to see through these early drawings how our lives were changing in tandem with the things around us. Drawing became the medium to understand what was happening. We stopped thinking about design for a moment, observations became more important than ideas, and to draw those transformations as they were happening in real time was the best architectural lesson we could have possibly had. How the things around us are organised determine the kind and the character of life’s possibilities. Indeed, media determined our situation.

Reaction 2

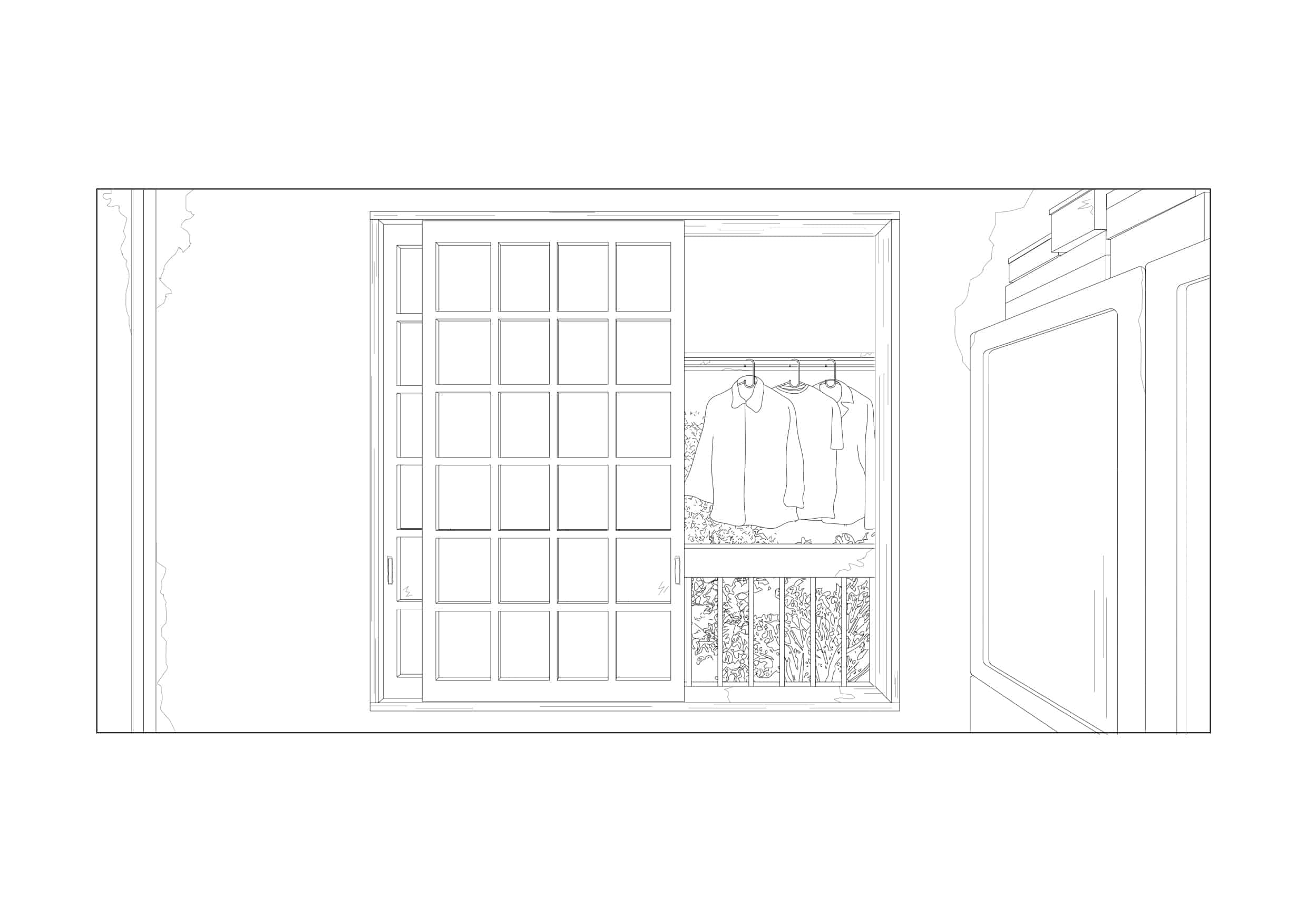

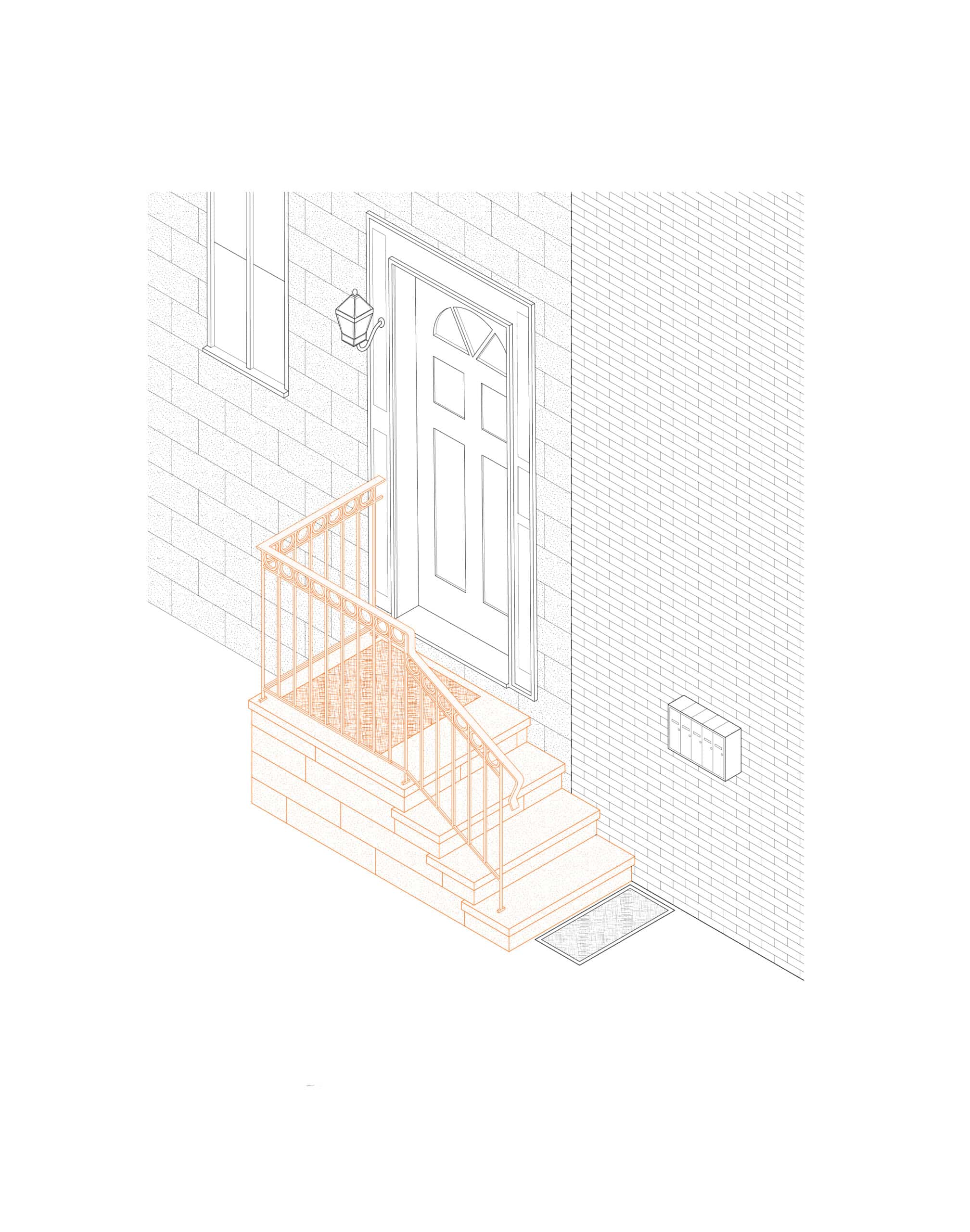

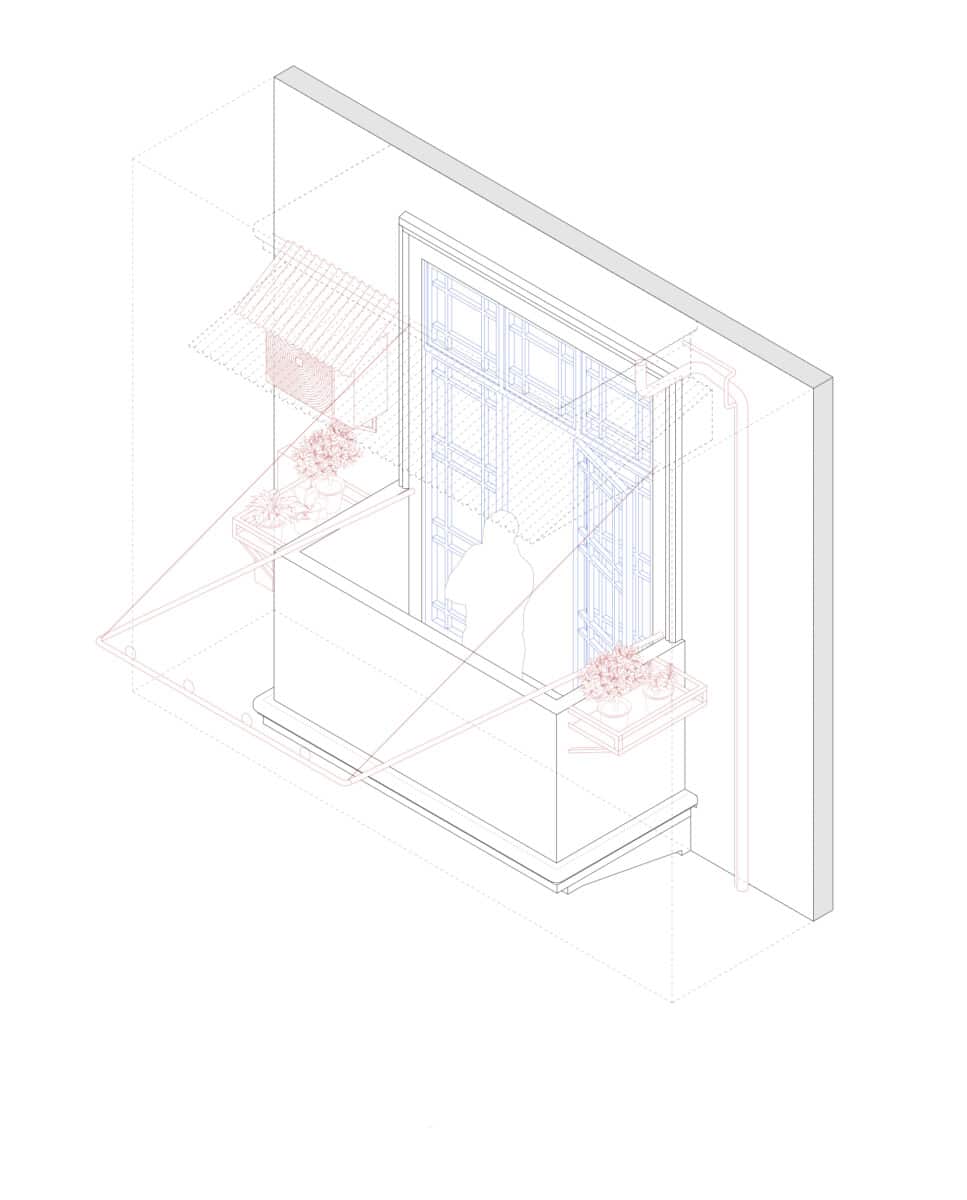

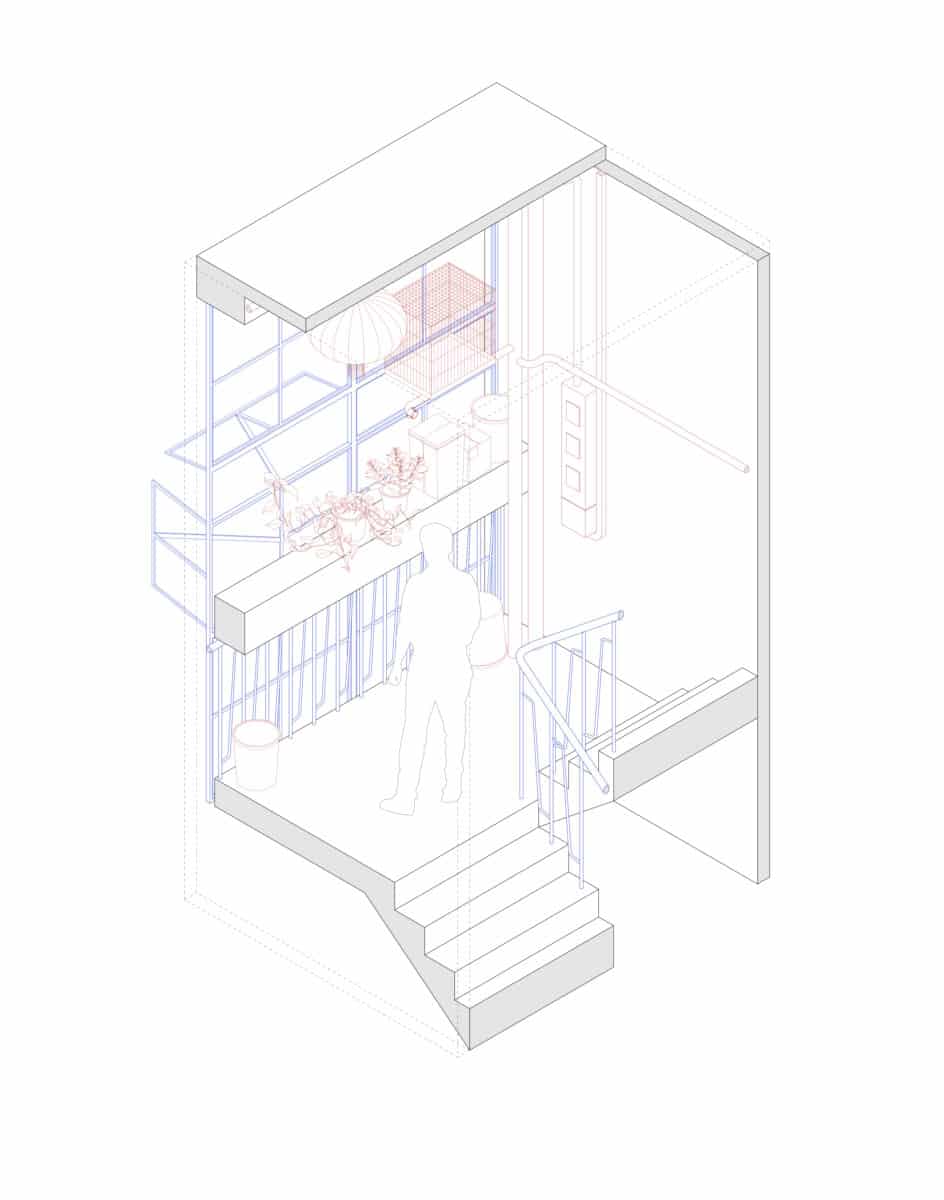

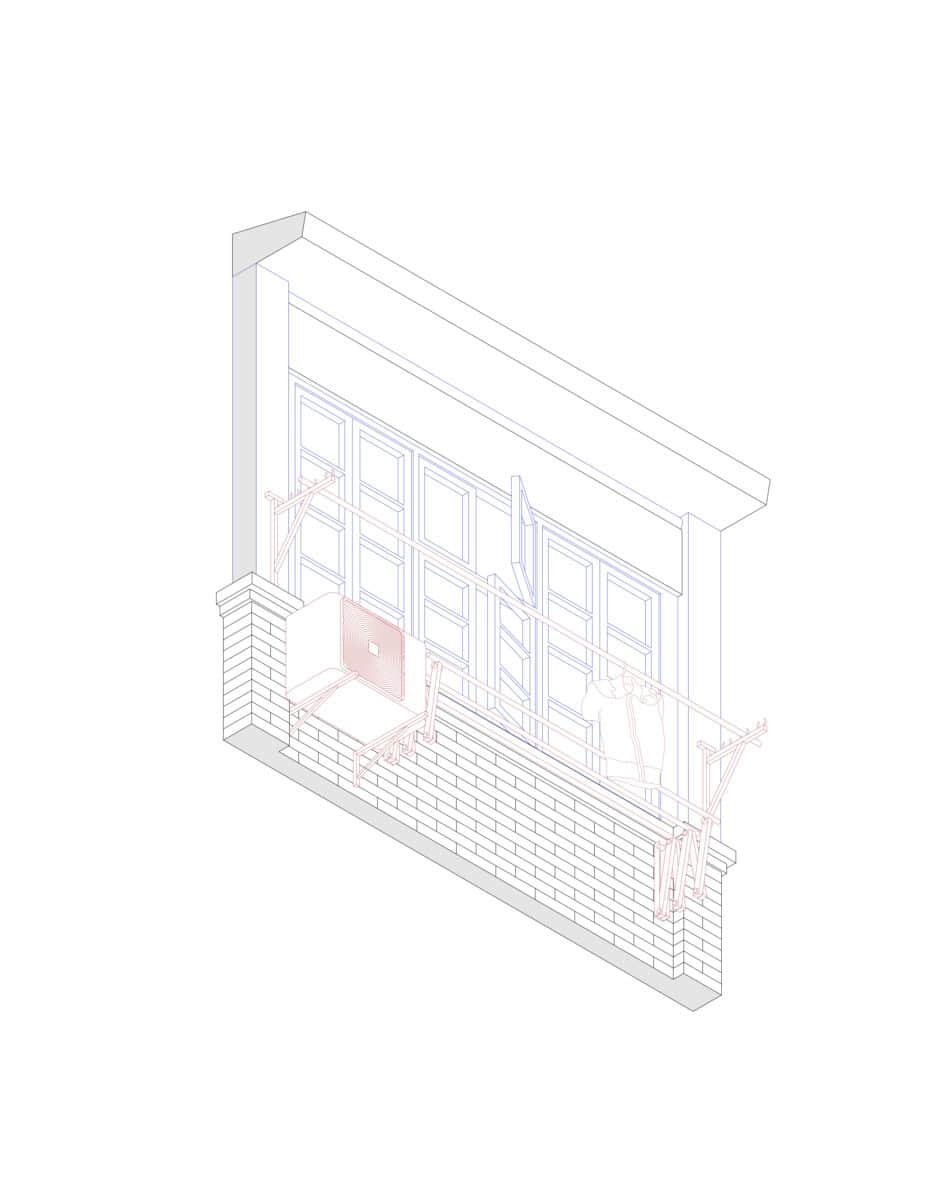

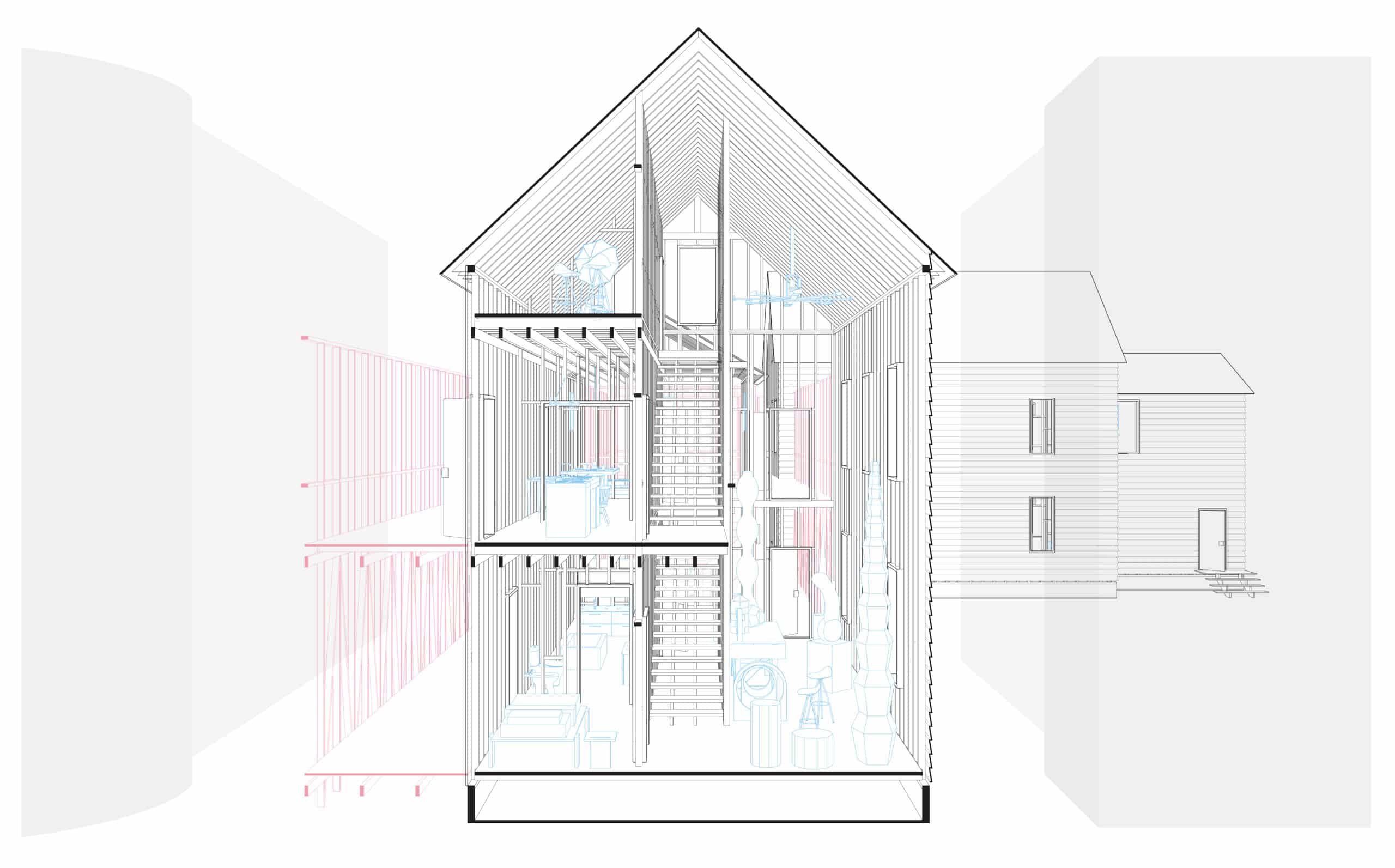

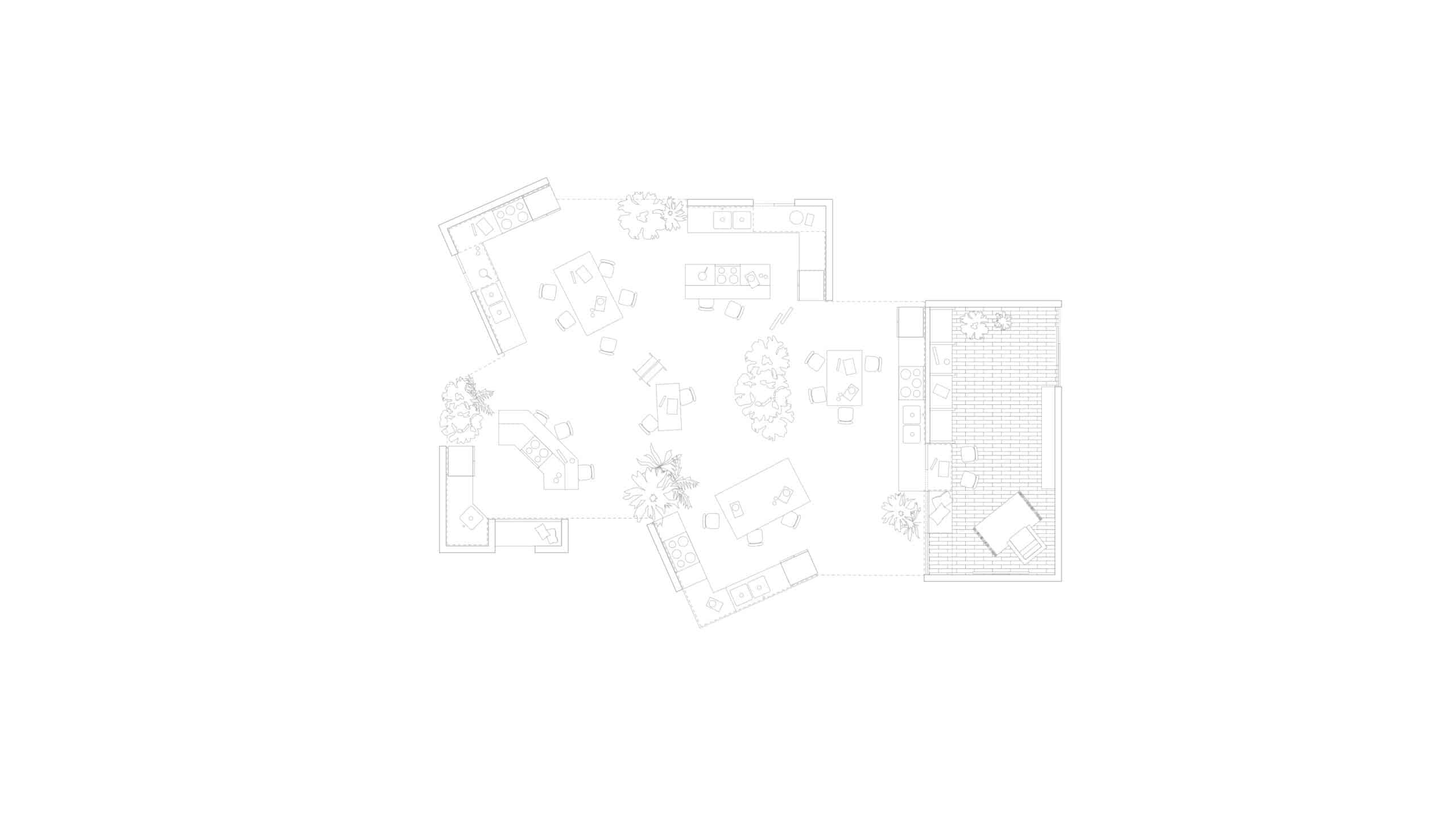

The summer passed and those of us involved in academia spent a little less time on screen. A new semester began, and this time, the faces on the screen were all new to one another. One student has a sleepy face, since she had just woken up in California at 7:00 am, another looks tired as the dark window behind her signals the early evening in Japan. The student in Paris is eating lunch as we discuss ideas, while I feel like doing the same thing in Berlin but simply cannot do it. However strange, that sheer reality was far too enticing as a spatial construction. A new interest in the ordinary emerged. I suggested to the students that they spend more time off the screen, and they began to document ordinary windows, stairs, and balconies wherever they were located. It was no longer the ordinary that we were looking at, but rather at the many different material conditions that we could share collectively and learn from. Even though it was difficult, another beautiful architectural lesson emerged out of those drawings.

Reaction 3

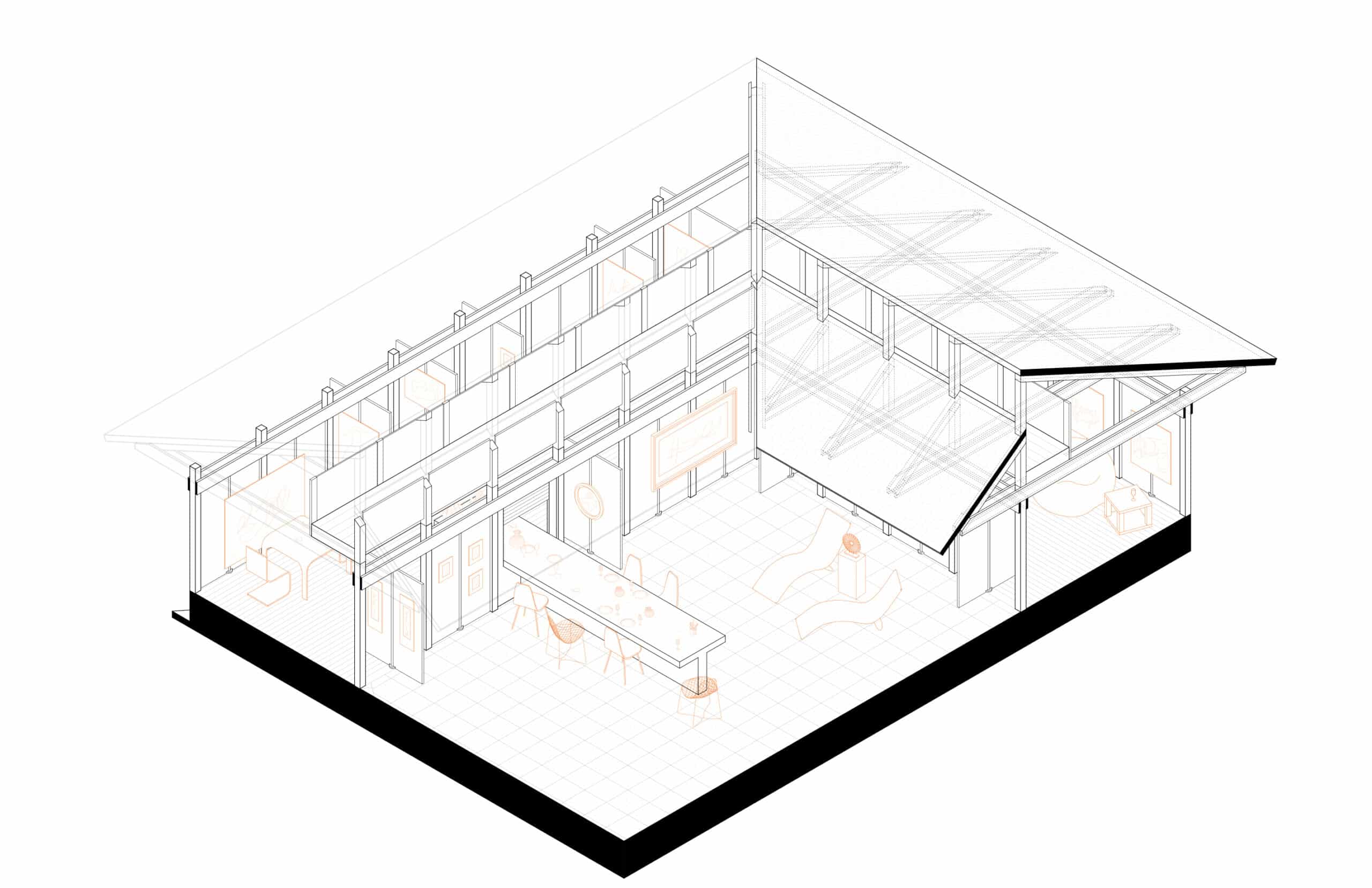

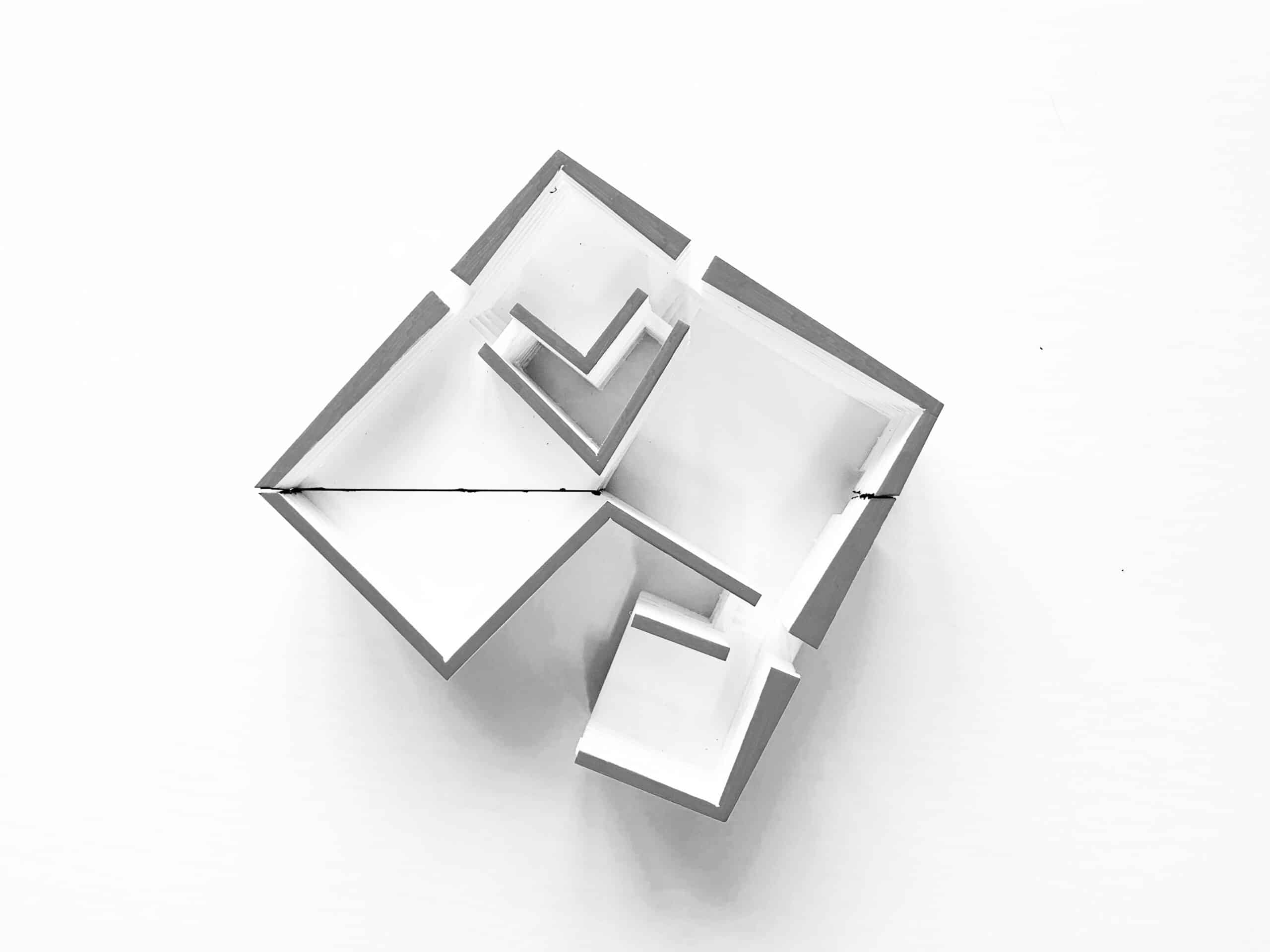

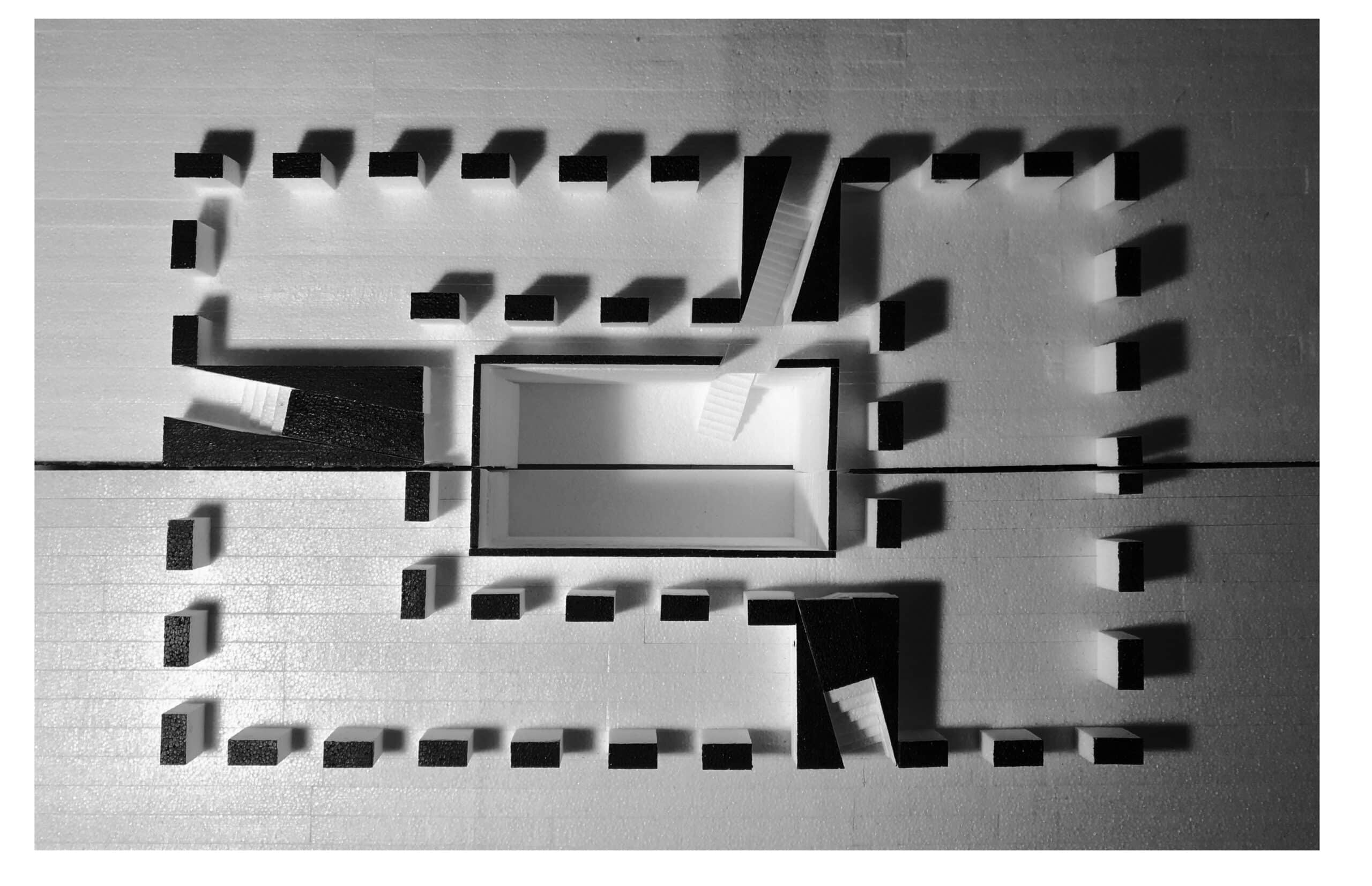

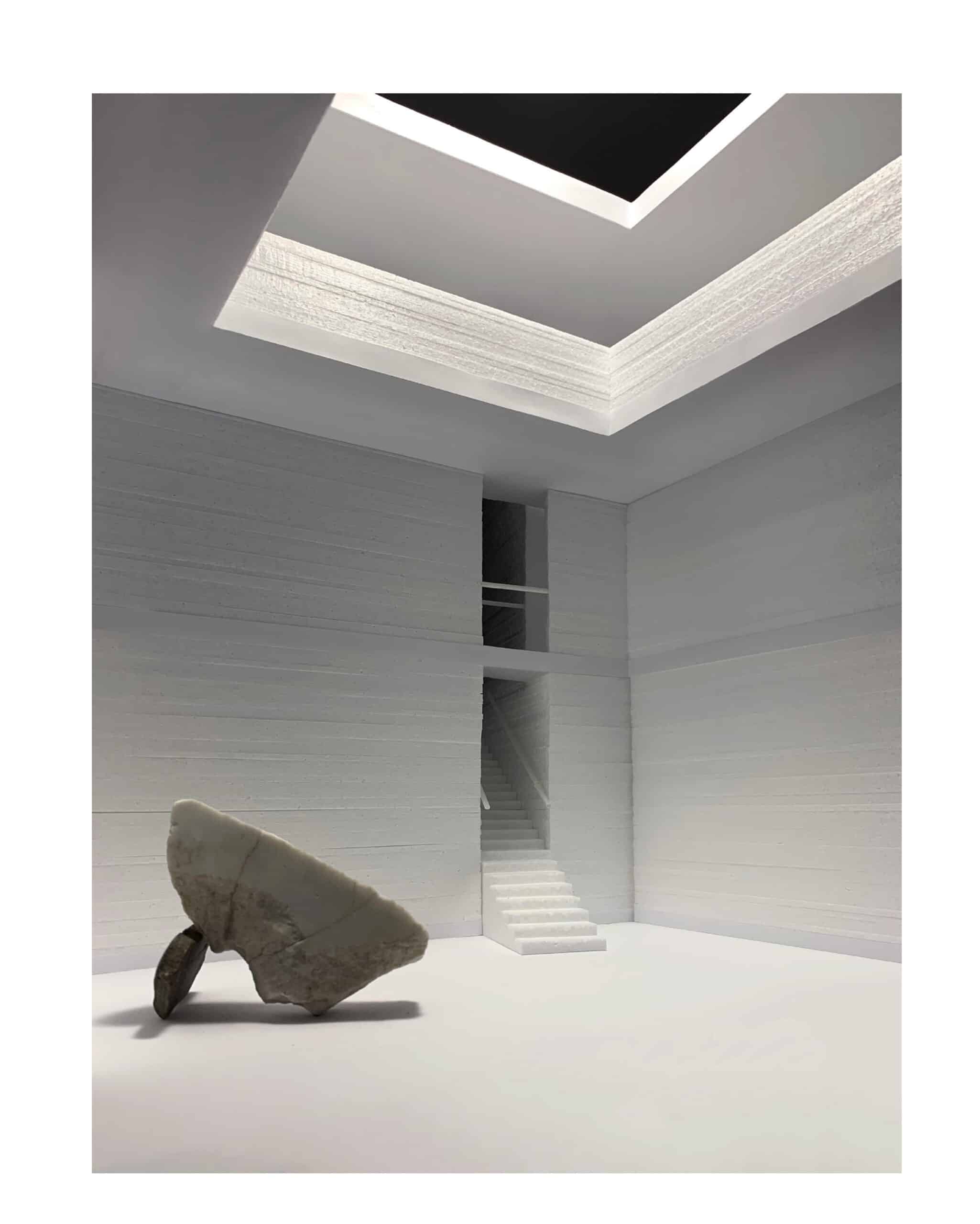

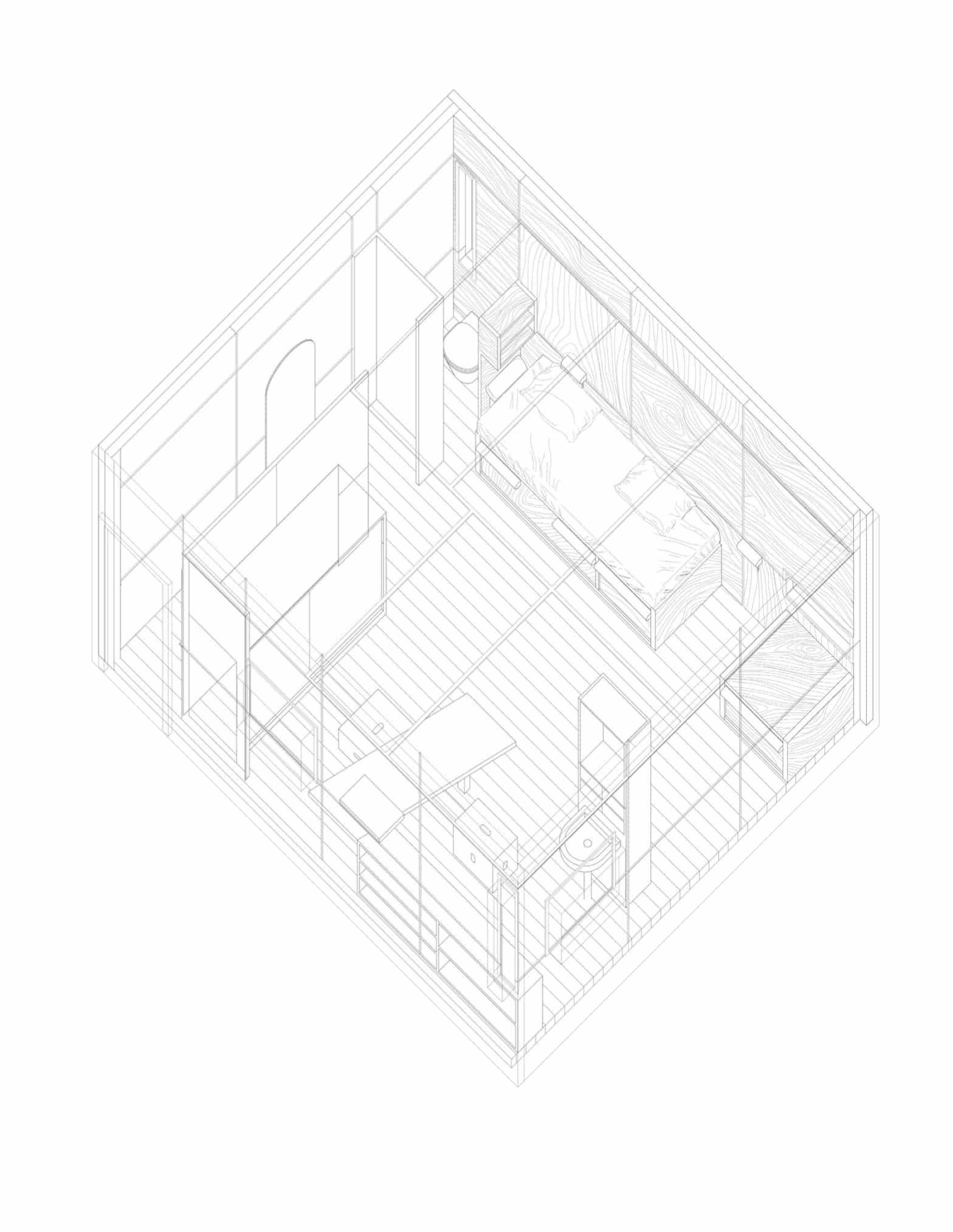

It was through the act of doing those drawings and focusing on the plurality of ordinary conditions that I realised the obvious fact that screens do not have scale. We could share an idea, read the same texts, look at the same image, and even listen to the same sounds, but we did not share the kind of space that allows you to look at things with the same degree of resolution. How was I supposed to speak about the relationship between matter and drawing in architecture to first-year students without scale? How could I make a first-semester student experience the fact that scale is not about the size of the drawing but rather about resolution – about what you see and don’t see – if you can always endlessly zoom on the screen? We reacted again, and we began to draw with models, physical models and photography. Then we were sure we had at least in common the 5mm thickens of the foamcore, and now abstraction took a new meaning. During those weeks, drawing meant for the students to meditatively cut layers of material and stack them. The camera made cardboard to appear on the screen as low-res scaled orthographic projections.

Reaction 4

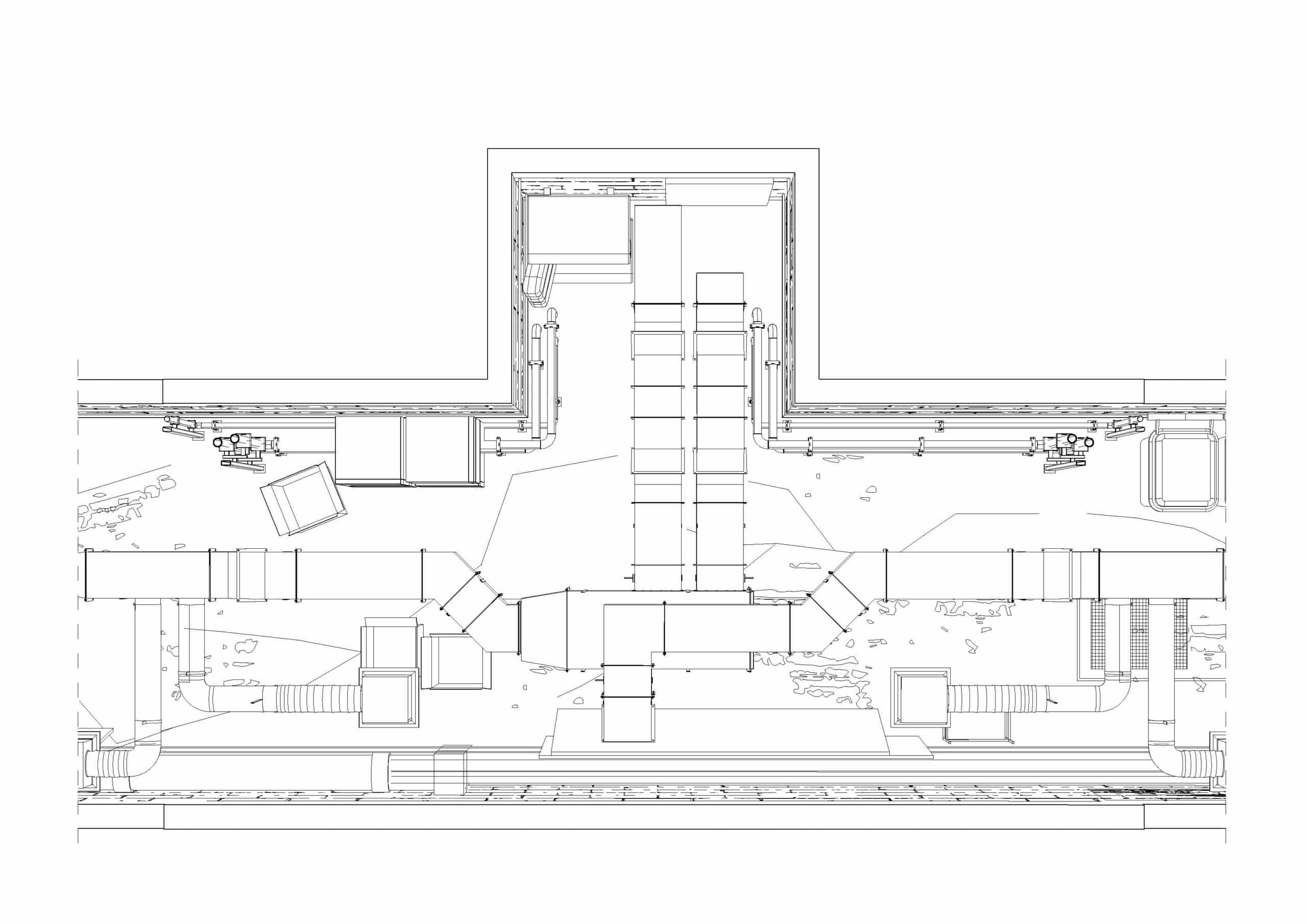

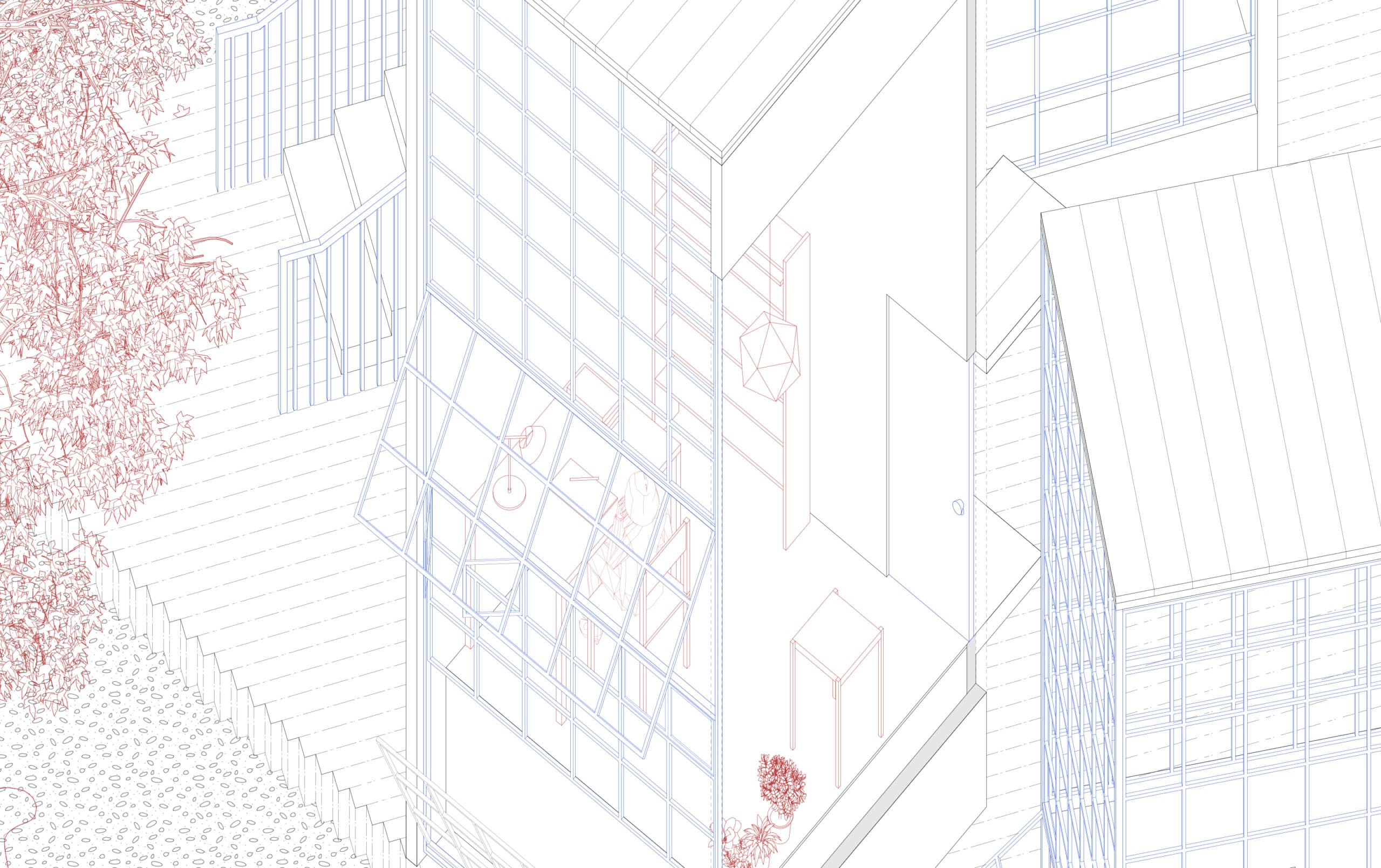

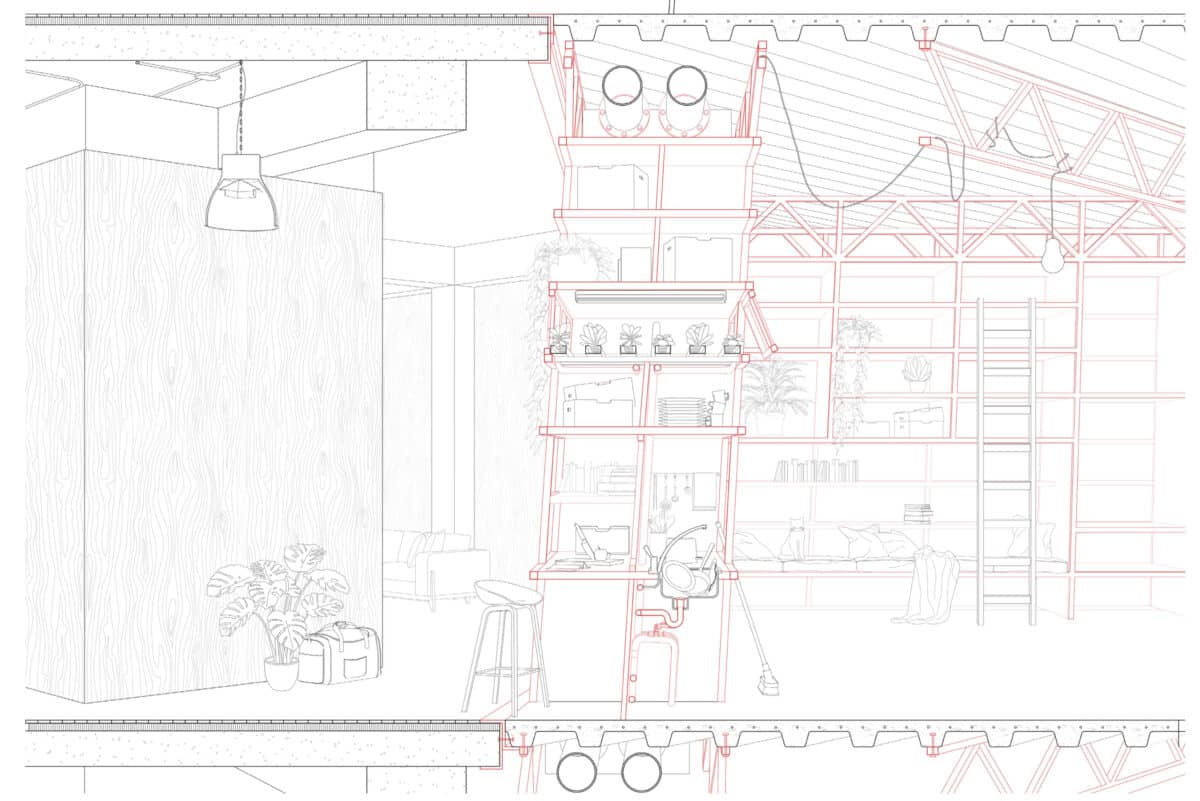

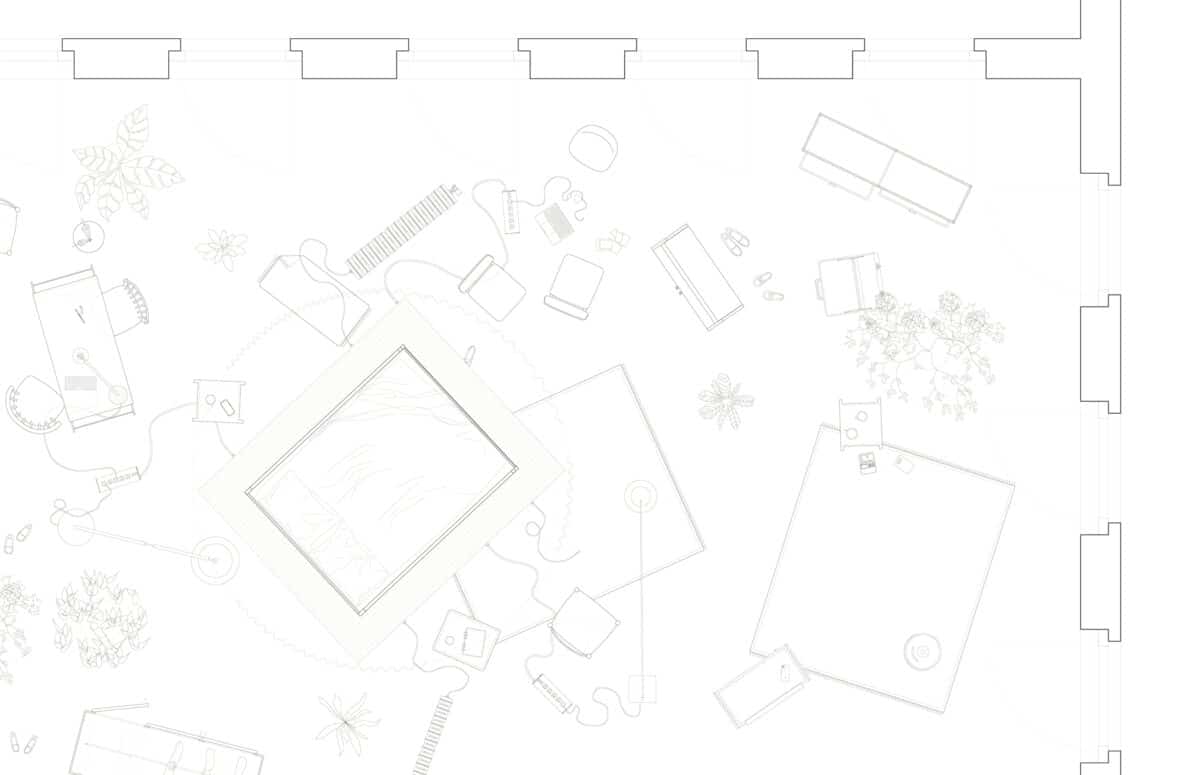

The other thing I realised when trying to come to terms with drawing on the screen was to think again about the importance of fragments. Essentially, the computer screen only shows you things in parts, it constantly resists the idea of a coherent whole. To zoom means to crop whatever is on the screen with a constantly shifting frame, thus real totality becomes simply impossible to grasp. I thought that that was an interesting opportunity again, to look critically at architecture through parts, first documenting and then designing in fragments. When looking back at the drawings we produced, pieces of furniture seem to resemble large buildings and I also see naturally emerging a total disinterest for composing façades and such. Plants began to be drawn more carefully than people inside the rooms, and piping and wiring became interesting to students for some reason. Just like Funes in the famous Borgesian story, my students became overly attentive to seemingly irrelevant aspects of the world around them, and, through the drawings, an architecture of the exception and the unpredictable idiosyncrasy merged with an architecture of the ordinary. As in Funes’ world, there was no abstraction.

Reaction 5

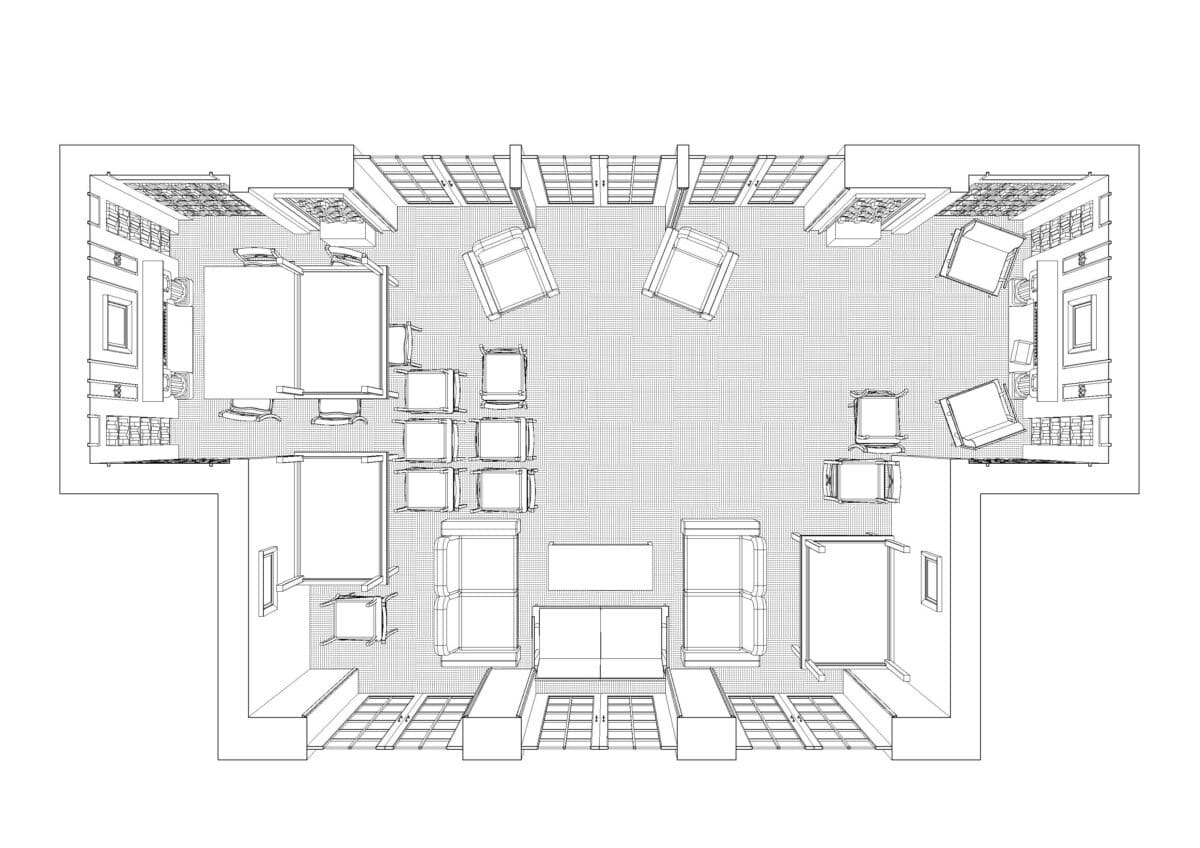

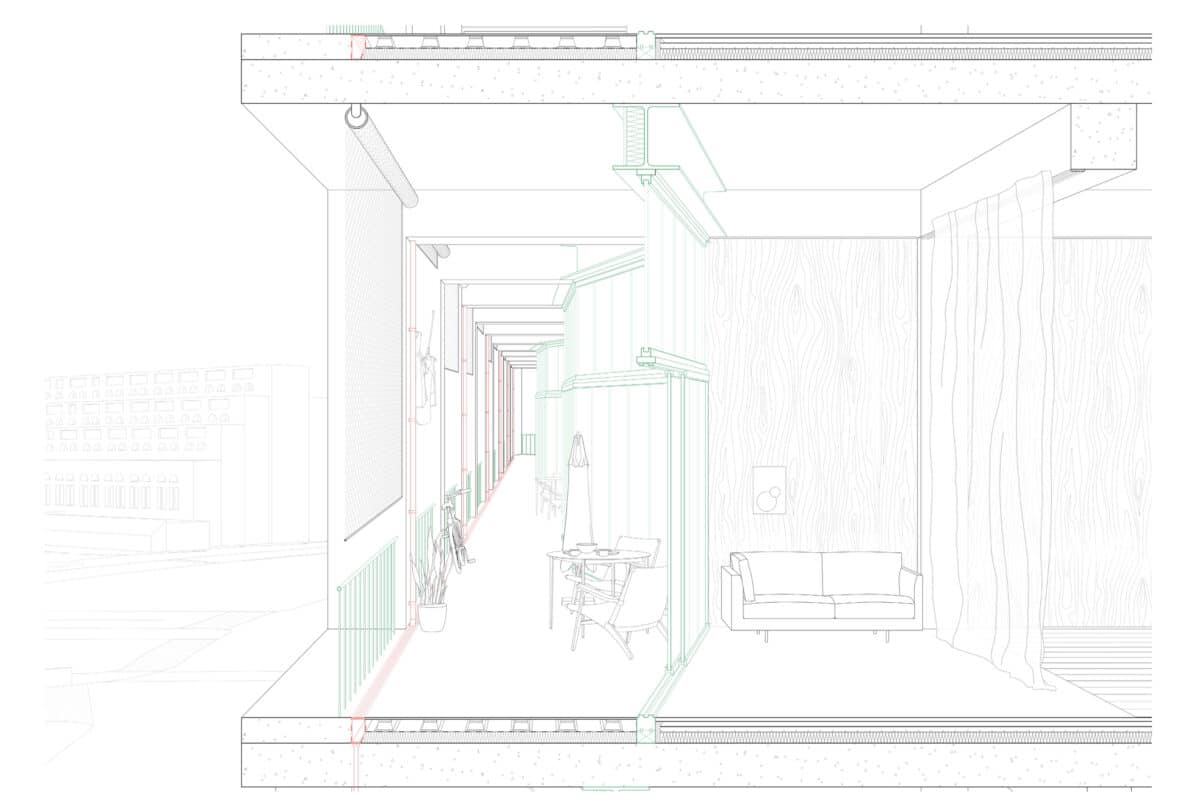

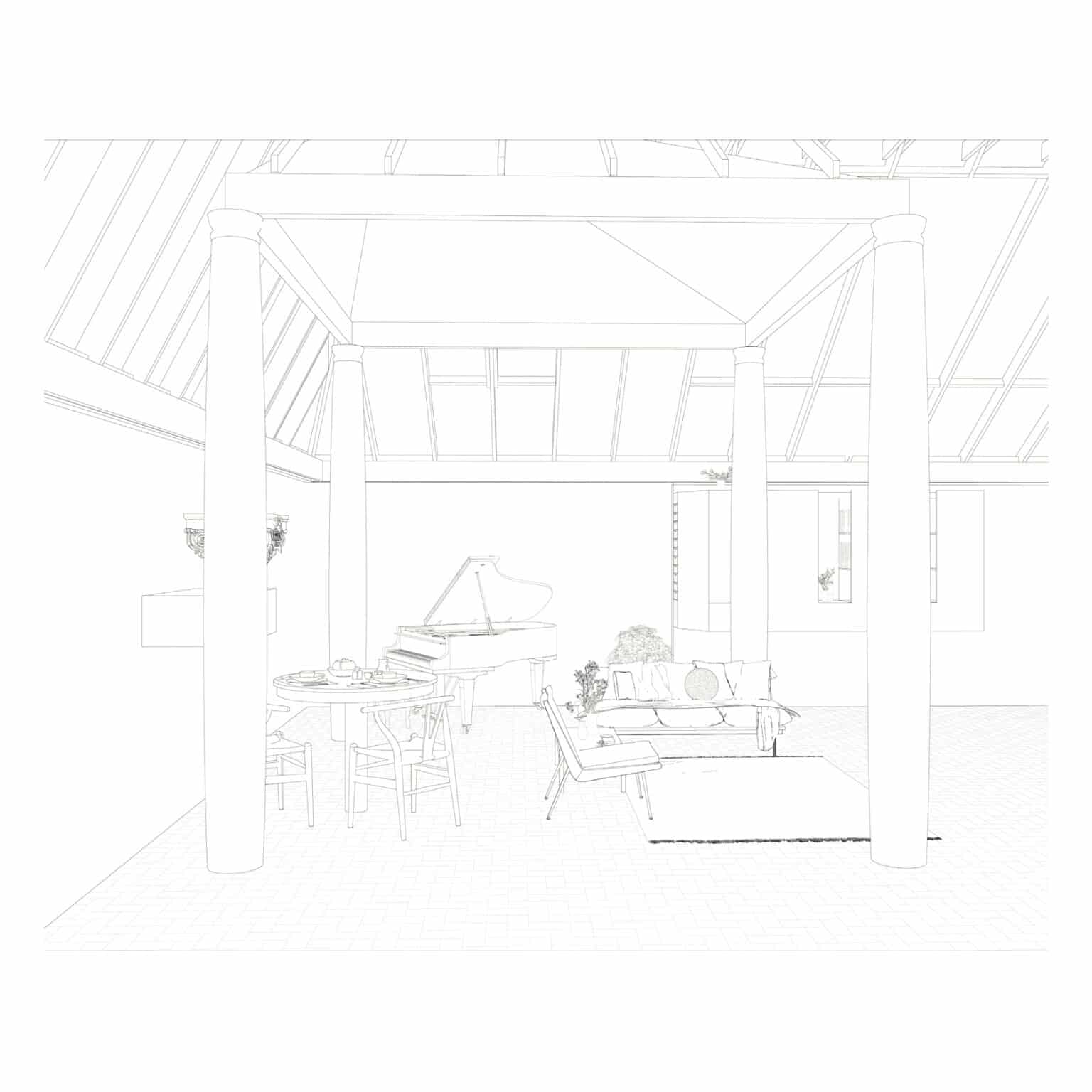

After a full year of deep diving into screens I finally realised that there was something special and interesting about the transformation of the actual rooms from where we were teaching and therefore drawing. We were not really in front of a screen but rather within a new form of architecture. I slowly began to understand how designed my improvised broadcasting studio was, with its particular acoustics, with a special artificial lighting, and equipped with a series of technical devices that made possible the fantasy of seamlessly drawing and sketching with my interlocutors dispersed all around the globe. The architecture of the room from where I was teaching, the very tool through which drawing in such way was made possible, was an architecture built out of a blend of rudimentary and relatively technical materials. In fact, our entire office turned into a broadcasting house of sorts, a sequence of independent rooms from where my colleagues and I began to broadcast content to different audiences, in different languages, and using drawing in various different forms. I would often find myself walking through the office passing from room to room, overhearing conversations of people with someone in China or in Chile. At the end, our office had blended teaching and practice, different countries and time zones, through a series of electronically equipped studiolos. Within them, us – the contemporary Saint Jeromes – have no longer opaque books and papers willing to be illuminated by our readings or sketches, but they are rather filled with luminescent screens from where our voices and line drawings are recorded and transmitted. I am curious to see how much of this remains, but I think I have come to terms with drawing.