Piranesi Unbound (2020): Review

There is much to admire in this sequel to Heather Hyde Minor’s Piranesi’s Lost Words (Penn State, 2015), which sets out to ‘explore new territory by reimagining his artistic production in terms of his books’. Whereas Lost Words drew attention to Piranesi as an author who combined texts and images to create architectural books of unprecedented rhetorical power, Piranesi Unbound attempts to trace representative stages in their often complex history. Unearthing a great deal of valuable new evidence, which is sometimes problematically interpreted and at others insightfully, as this review discusses, the authors succeed in evoking the whole range of different processes and people involved in the production and dissemination of Piranesi’s books, down to and including the varying fortunes of specific copies, each of which has a unique tale to tell regardless of whether it is now a prized possession safely ensconced in a library, or a sad wreck gutted of its plates for the art market.

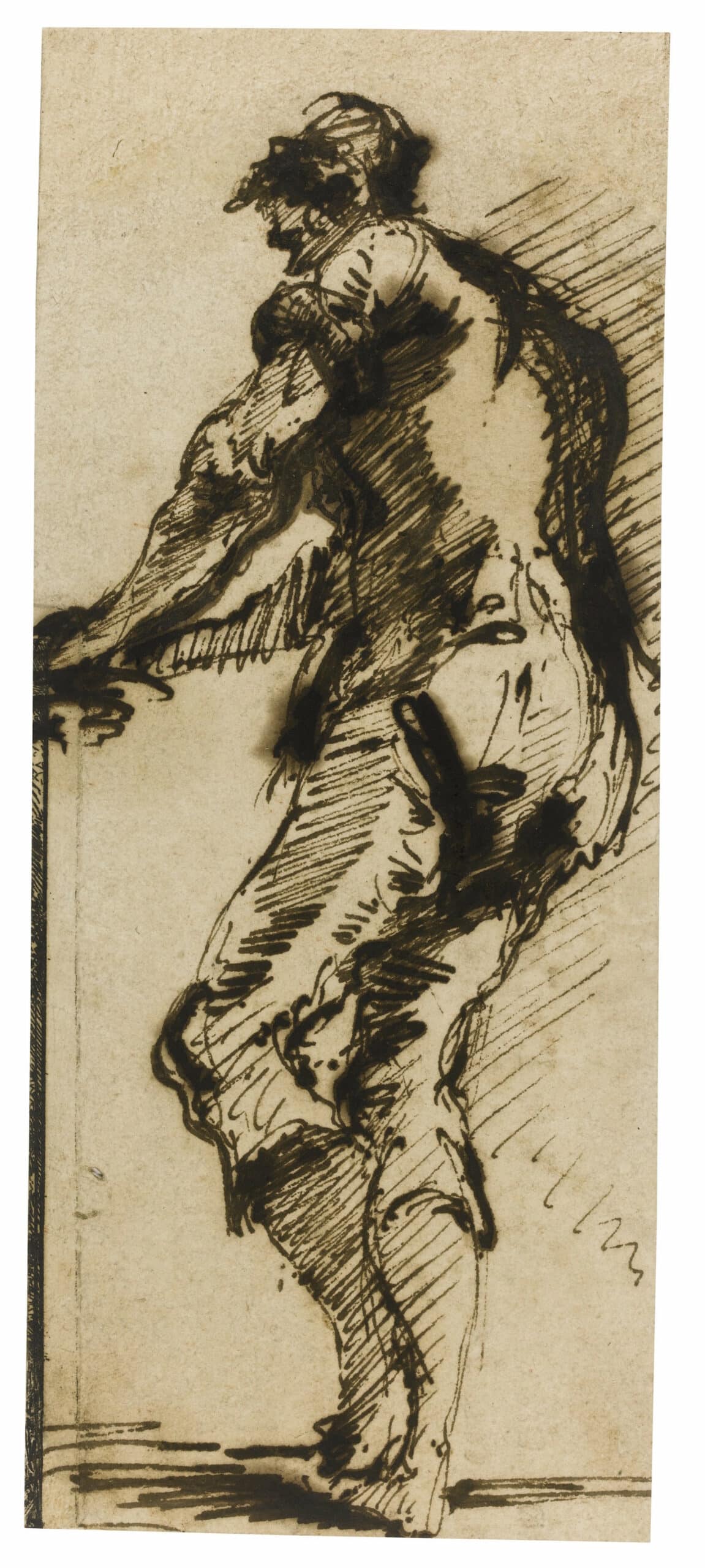

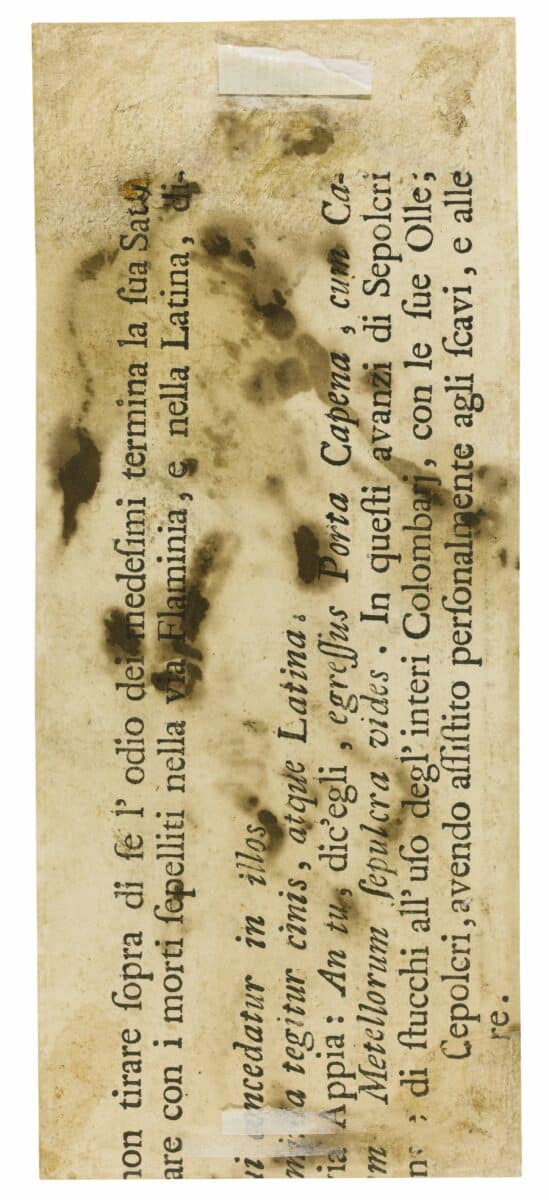

Signing their respective contributions individually, the authors begin in classic detective fashion by going through Piranesi’s wastepaper basket – it turns out over sixty Piranesi drawings survive ‘on paper that has some form of printing on it’ – and are immediately rewarded with the discovery of a ‘lost’ book. Decipherable only from enigmatic slivers of a titlepage imprint and two fragments of letterpress, this is enough to identify their find as the only known remnants of a folio volume printed for Piranesi in Rome by Angelo Rotili in 1753 but never published. Carolyn Yerkes is almost certainly right in associating this ‘abandoned’ publication with an abortive transitionary phase in the complex evolution of Piranesi’s first major book, the four-volume Antichità Romane printed by Rotili three years later. For Hyde Minor however, the experience of going through ‘Piranesi’s trash’ is exciting above all because it ‘allows us to stand in a corner of his busy workshop as viscid ink is applied to fresh copperplates, and to sit at a compositor’s table [sic] as he assembles glyphs [i.e. type] into text.’

Instructive as this may be for her, I cannot help thinking that ‘the complicated and difficult process by which Piranesi’s books came together’ would have been better demonstrated had the author not merely recounted the already well-known backstory of Piranesi’s notorious quarrel with Lord Charlemont over the dedication of the Antichità Romane, but gone on to consider how the last-minute suppression of its earlier incarnation lends credence to Charlemont’s agents’ complaint that he had tried to bamboozle his lordship into sponsoring an entirely different book from the one he had at first proposed. Instead, the author asks us to ‘reimagine’ the drawings Piranesi made on printer’s waste as intentionally ‘composite work[s] of art’, analogous in their different ‘layers’ to the historical layering of Rome’s monuments. What brings this flight of fancy back down to earth is the fact that Piranesi had a perfectly straightforward housekeeping reason for using up odd scraps since paper was, as both authors acknowledge – Hyde Minor belatedly and Yerkes upfront – ‘by far the most expensive component of an early modern book.’ Somewhat deflating also is the fact that, with the single exception of a pen-and-ink sketch at Princeton, the drawings Hyde Minor cites simply do not justify this reading of them as meaningfully ‘composite’, except in the most literal, documentary sense. As for Yerkes’ claim that ‘Piranesi used the marks on the page from previous printing proofs as guides, so that each figure is orthogonal to the existing lines, printed words and edges of the paper’, this describes so universal an aspect of drawings in general that it tells us nothing in particular about Piranesi or the way he worked.

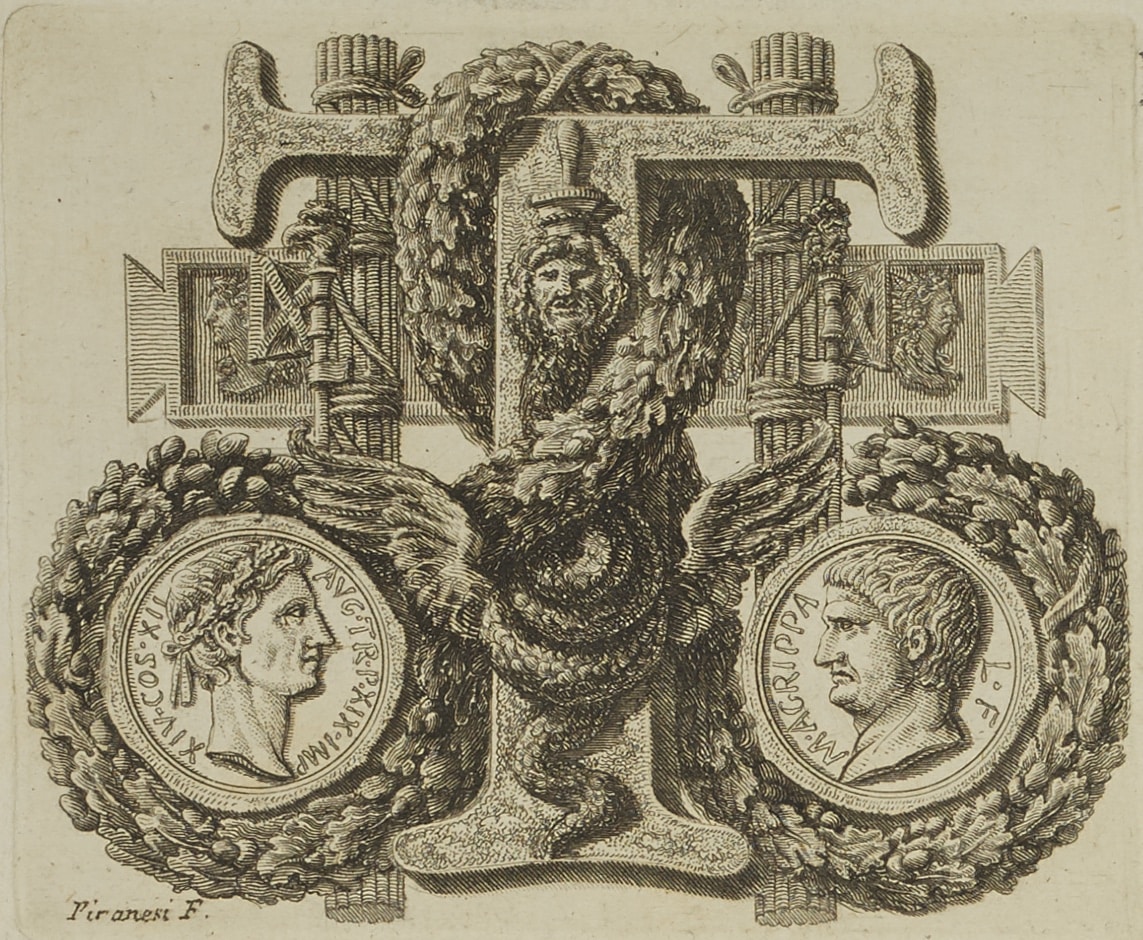

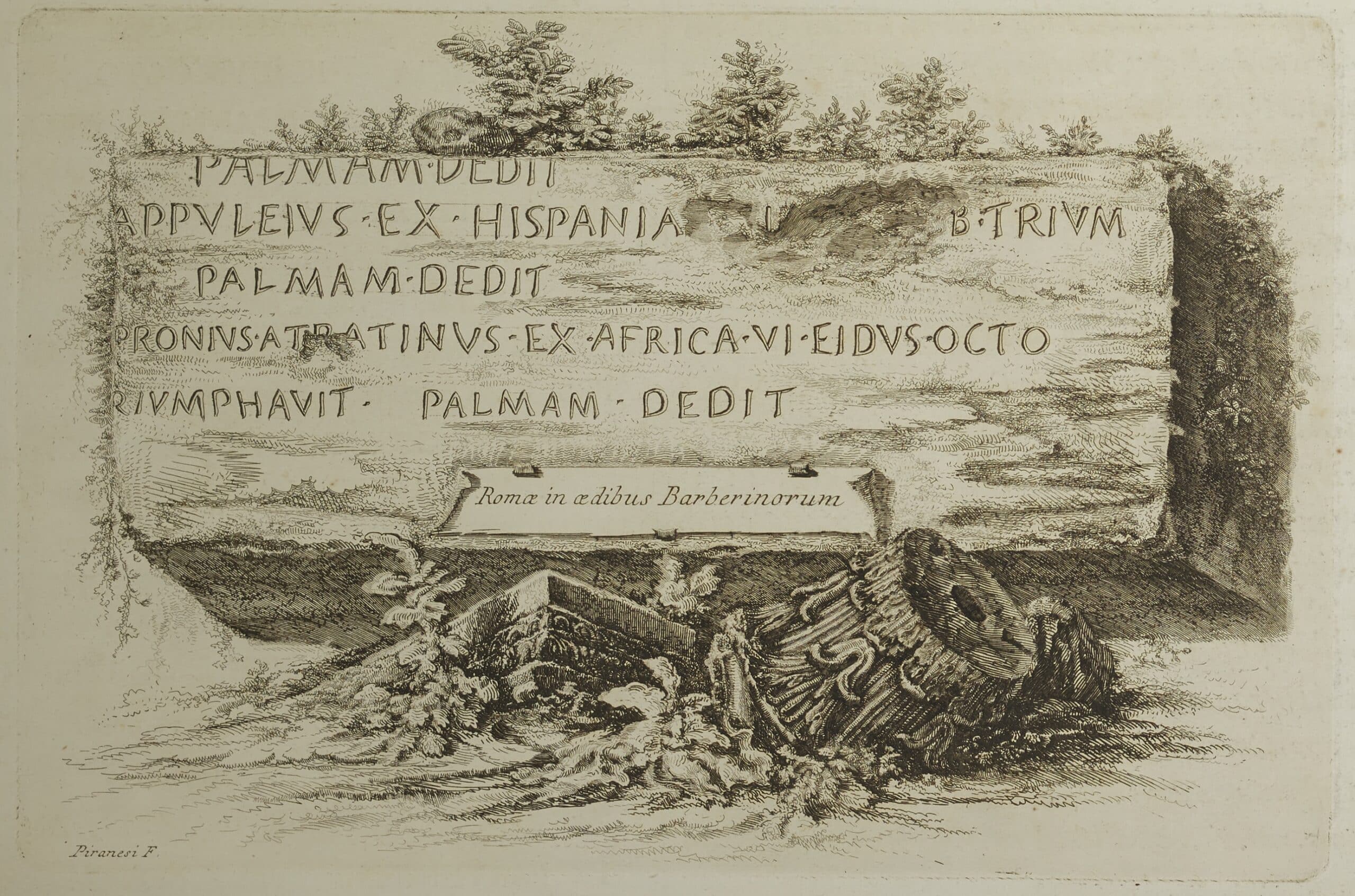

Fortunately, both authors are on much firmer ground in their subsequent chapters. Yerkes’ thoroughgoing survey of Piranesi’s usually-overlooked ‘vignettes’ (i.e., the engraved initials and head- and tail-pieces that were practically de rigueur in an eighteenth-century folio) emphasises quite rightly how they reveal his longstanding fascination with and deep knowledge of ancient coins and inscriptions, and how he revelled in the licence possible in the decorative elements of his books to embroider fact with fiction. Similarly, in her chapter on bindings Hyde Minor’s conducts an exemplary masterclass in how to unpack the whole history of a book’s reception from the provenance of specific copies. Here and indeed throughout their book both authors are notably generous in sharing via footnotes their immense knowledge of Piranesi and his works. I was particularly grateful to discover for instance that ‘Buzard’ – Piranesi’s deliberate misspelling of ‘Bouchard’, the publisher of the first issue of the Carceri – translates as ‘bugger’ in Venetian.

Piranesi Unbound (2020) by Carolyn Yerkes and Heather Hyde Minor is published by Princeton University Press. Copies of the publication can be purchased, here.

Nicholas Savage is an architectural historian and former Head of Collections at the Royal Academy of Arts.