Raffaello. Nato architetto (2023) – Review

Architectural history is a delicate matter when it comes to exhibitions: especially, if the subject is a creator like Raphael (1487-1520) whose work as a designer, despite its relevance, survives in a dramatically fragmentary state. Thus, it can only be reconstructed by means of analytical philology, mostly using secondary sources, with a handful of original documents. Inevitably, in this type of reconstruction, the role played by the study of drawings and other graphic materials is a major one. The exhibition Raffaello. Nato architetto, which was on show at the Palladio Museum in Vicenza between April 7 and July 9, 2023, fully embraced this challenge, responding to constraints in a manner that was both creative and engaging. The exhibition followed a conference organised in 2020 (a year of ubiquitous commemorations marking the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death) by Max Planck’s Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz and the CISA ‘Andrea Palladio’ (the research centre from whose rib the museum was created). It was conceived by the CISA’s director, Guido Beltramini, together with Howard Burns and Arnold Nesselrath, both permanent members of the centre’s scientific committee and instrumental, years earlier, in a pivotal exhibition for the celebrations of Raphael’s birth in 1984, which counted amongst its curators Christoph Frommel and Manfredo Tafuri. That crucial episode in architectural historiography had already revealed to the discipline the extent of the complexity and influence of Raphael’s work as a designer. Its catalogue still stands as a watershed for the study of Renaissance architecture because it set a standard for several methodological tools, such as the close observation of drawings as documentary sources; the reconstruction of the process of design as a complex, sometimes contradictory phenomenon; the analysis of building techniques, to a certain degree; and especially the linguistic and political reading of 16th century appropriations of the antique. Inevitably, this historiographic achievement was the benchmark for the Palladio Museum’s exhibition on Raphael’s architecture on show almost forty years later.

Still, the 2023 exhibition—despite the smaller size, or maybe, precisely thanks to this characteristic—took a step further. It displayed a more articulated comprehension of Raphael’s architecture that has stemmed in recent decades from the scholarship of the 1980s, as well as a mastery in the design of exhibitions devoted to the architecture of the past that has been developed in the highly experimental context of the Palladio Museum. Indeed, Raffaello. Nato architetto was an exhibition that openly declared and made visible the doubtful, often labyrinthine, open-ended nature of research, while simultaneously making it charming and easy to understand. Exceptionally, visitors were asked to interact with the same tools that are available to architectural historians and, quite literally, to put their hands on the scholar’s desk, represented by movable wooden tables dotted amongst the visual narrative of the show. As a counterpart to the lavishness of the 16th century interiors of Palazzo Barbarano, they were often the focus of the room, displaying finished models as well as working maquettes, facsimiles of drawings enriched with annotations, and other informative materials such as labels, measuring scales, and timelines. These were among the museological strategies that have been perfected by the Palladio Museum in previous years, but on this occasion, they were developed by architect and set-designer Andrea Bernard into an even more engaging set of scenographic devices—such as the large curtains with to-scale reproductions frescoes form the Vatican Stanze—which offered an emotional immersion into Raphael’s architectural imagery.

The exhibition opened with an introductory section providing the coordinates of Raphael’s biography, while also illustrating his long-life interest in architectural forms. With this intention, the first room was dominated by two facsimile reproductions, crafted by the renown specialists Factum Arte, of the cartoons produced for the weaving of the monumental tapestries destined to the Sistine Chapel, now in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. As explained in Maria Beltramini’s essay in the exhibition catalogue, their architectural landscapes, which have been mostly overlooked, since they are positioned on the scenes’ background, demonstrate Raphael’s keen knowledge of architecture and display his multifarious sources of inspiration. The following section illustrated the context of Roman antiquarianism in the early 16th century by orchestrating a dialogue between printed treatises—such as Fabio Calvo’s Urbis Romae Simulacrum, Fra Giocondo’s edition of Vitruvius, and Sebastiano Serlio’s Third Book—Raphael’s intellectual interlocutors—particularly Pietro Bembo and Baldassarre Castiglione, portrayed in two bronze medals—and drawings. Especially noteworthy among a handful of surveys after the antique, studied in in the catalogue by Timo Strauch, was the lively autograph sketch with details of the interior of the Pantheon that vividly documents Raphael’s assimilation of the painterly quality of ancient architecture. The so-called Letter to Leo X (i.e., Raphael’s only theoretical writing, known from two manuscripts, that establishes a scientific method for archaeological surveys) was the subtext to the entire section and was therefore evoked by reconstructions of measuring devices and Niccolò Tartaglia’s treatise on topographic compasses.

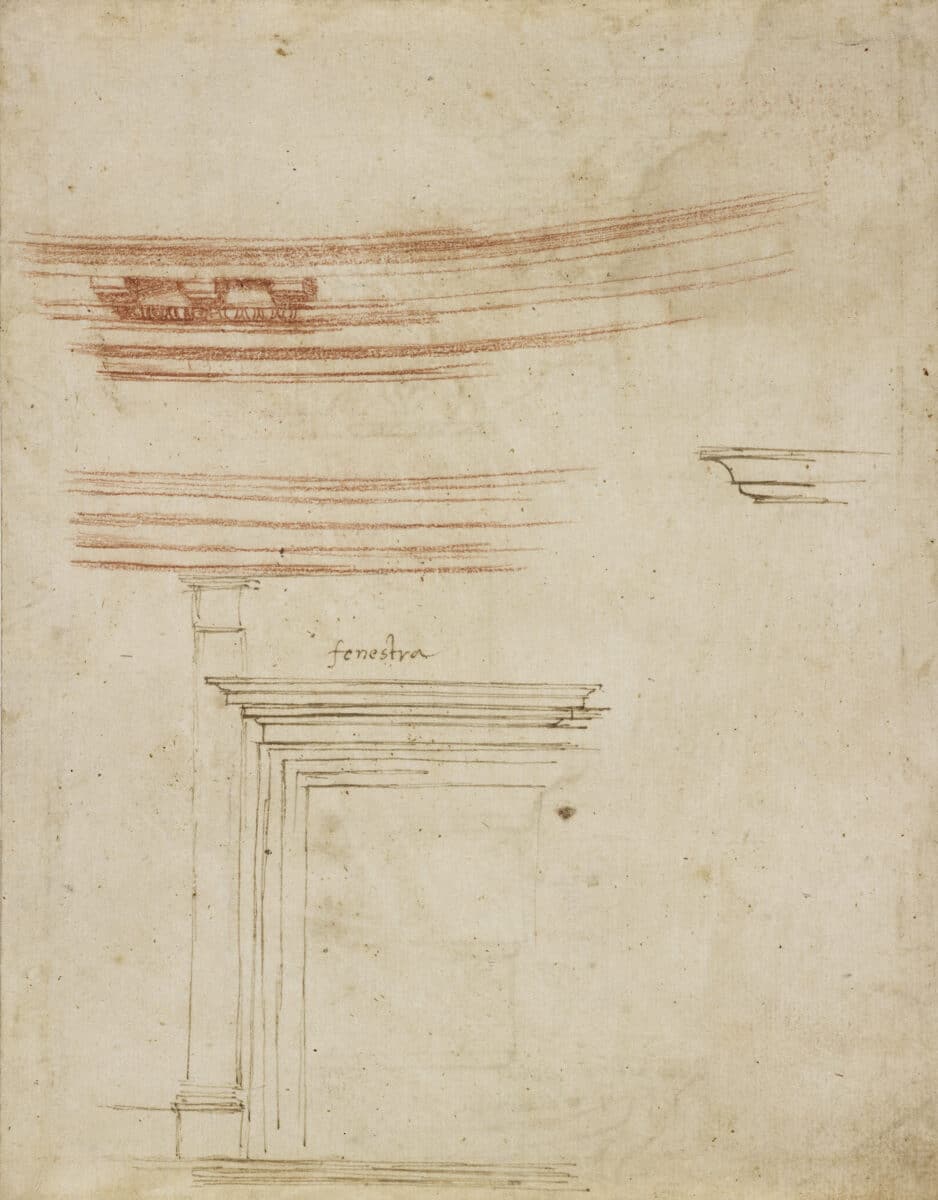

More 16th century drawings were exhibited in the following sections—among others, Raphael’s own sketch of a cornice for Palazzo Alberini, Palladio’s survey of Villa Madama, a set of copies by Antonio da Sangallo and collaborators after a Raphaelesque project for a house on Via Giulia. However, since the remaining rooms focused on residential projects, reconstructive models almost upstaged other objects, being the ultimate product of the research grounding this exhibition. It is disappointing that a similar effort to dissect Raphael’s incessant work of formal refinement was not made to untangle his projects for the most challenging building site he directed: the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica, which was illustrated in Vicenza only by a facsimile of New York’s Codex Mellon, opened on the two pages illustrating his inventive proposal for the elevation of the large church. But the decision to focus just on Raphael’s city palaces and his one design for a suburban dwelling, was justified by the depth of analysis showed by the reconstructions. A comparable insight could have hardly been constrained within a single exhibition section for a project as complex and long-lasting as St. Peter’s. Most importantly, the exclusion of this and other projects (indeed, the much altered palace for Jacopo da Brescia, the Chigi chapel and the small church of Sant’Eligio degli Orefici, in Rome, were also left aside, as it was for the supposed proposal for the façade of San Lorenzo, in Florence) can be better understood when considering the vocation of the Palladio Museum to engage especially with residential architecture. It is not by chance that the models produced for the show have subsequently become part of the permanent collection, showing the impact that Raphael’s projects for private residences had on the design practice of Palladio. Even the essay by Amedeo Belluzzi in the catalogue, which is the only contribution not related to objects or projects illustrated in the exhibition, subtly reconsiders the problems of authorship for another residential building traditionally attributed to Raphael, Palazzo Pandolfini. Ultimately, the essay contests this last hypothesis, thus shedding new light on both typological issues (many of the project’s anomalies were explained by reconstructing its original function as a casino rather than as proper palace) and the relationship of the project with the following generation of architects working between Rome and Florence.

While models took over in the second and most innovative part of the exhibition, they were never conceived of as finished artefacts, but rather as the visualisation in three dimensions of problems revealed, since they mostly illustrated projects that had been either abandoned or demolished. Therefore, while they served the primary function of ‘exhibiting an absence’—a formula often employed by the museum’s curators—they also reconstructed as literally as possible the various pieces of information provided by different graphic sources, even when in contradiction with each other, to the point that they might be considered as a critical commentary on the corpus of early modern drawings documenting Raphael’s architecture (a methodological aspect straightforwardly discussed by Simone Baldissini and Francesco Marcorin in the catalogue). This was particularly evident in the project of Villa Madama—formerly, the villa of popes Leo X and Clement VII—part of which still stands on the slope of Monte Mario, in the outskirts of Rome. Almost like the result of archaeological excavation in its aspect, the white and gilded model insisted particularly on this topographic dimension, testing the solutions formulated to overcome the challenge of height differences, at moments revealing their unsolved aspects. In so doing, it illustrated with eloquence the hiatus between diagrammatic, two-dimensional schemes such as ground plans and their volumetric development: a distance that commonly characterised past design practice, especially in this moment in the history of architecture. A similar approach was taken in the last room of the show, where the large table devoted to the demolished complex of the Stalle Chigi exhibited, among other drawings and maquettes, two different reconstructions of its façade based on contradicting sources, thus leaving to the observer the decision whether to untangle the conundrum or leave it as such. Using a different approach, the display on the wall behind illustrated Palazzo Alberini by capturing the most prominent formal strategies of its elevation: those of a flat screen subtly articulated by a sequence of shallow depressions. An enlargement of the cornice’s mutules, hanging above, was aptly lit to show the attention that Raphael paid to the shadowy effects of mouldings in a façade of this kind, which could (and can) only be observed from a lateral viewpoint. Indeed, since this is the one case in which Raphael’s project still survives in its integrity, the actual building might have been illustrated at a larger scale, instead of via the small photographic reproduction appearing to one side. This would have shown its material qualities, which were difficult to grasp from the whiteness of the model, to a general audience.

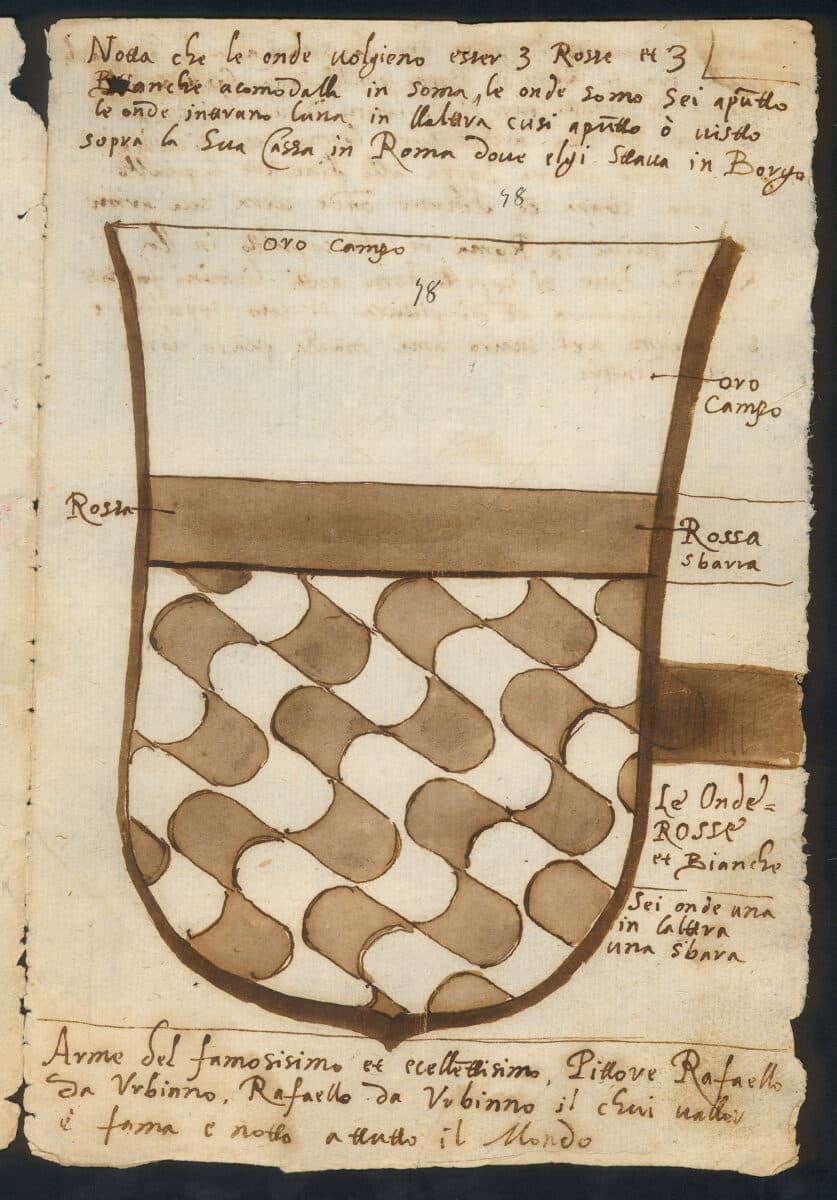

Finally, the treatment of the unrealised project for Raphael’s own palace on Via Giulia, later reworked by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, explored the project by means of computer-aided modelling, i.e., through a video responding to the spatial complexity of the scheme. This approach was responsive to the many uncertainties inherent in interpreting the ground plans: for instance, the problematic dimensions of the architectural orders appearing on the façade. This section provided the opportunity to reconsider a famous drawing in the RIBA collection: the perspectival view of Bramante’s Palazzo Caprini, which became Raphael’s private residence in the 1510s, a few years before his death. Although traditionally attributed to Palladio (because of its provenance), the catalogue essay by Guido Beltramini demonstrates that it was executed decades earlier and also adds a philological novelty, such as the newly presented reconstruction of the speaking to the representational function of private architecture in Rome during the reign of Leo X using the newly presented reconstruction of Raphael’s coat of arms, reconstructed through the interpolation with a codex now in Perugia: a detail speaking to the representational function of private architecture in Rome during the reign of Leo X.

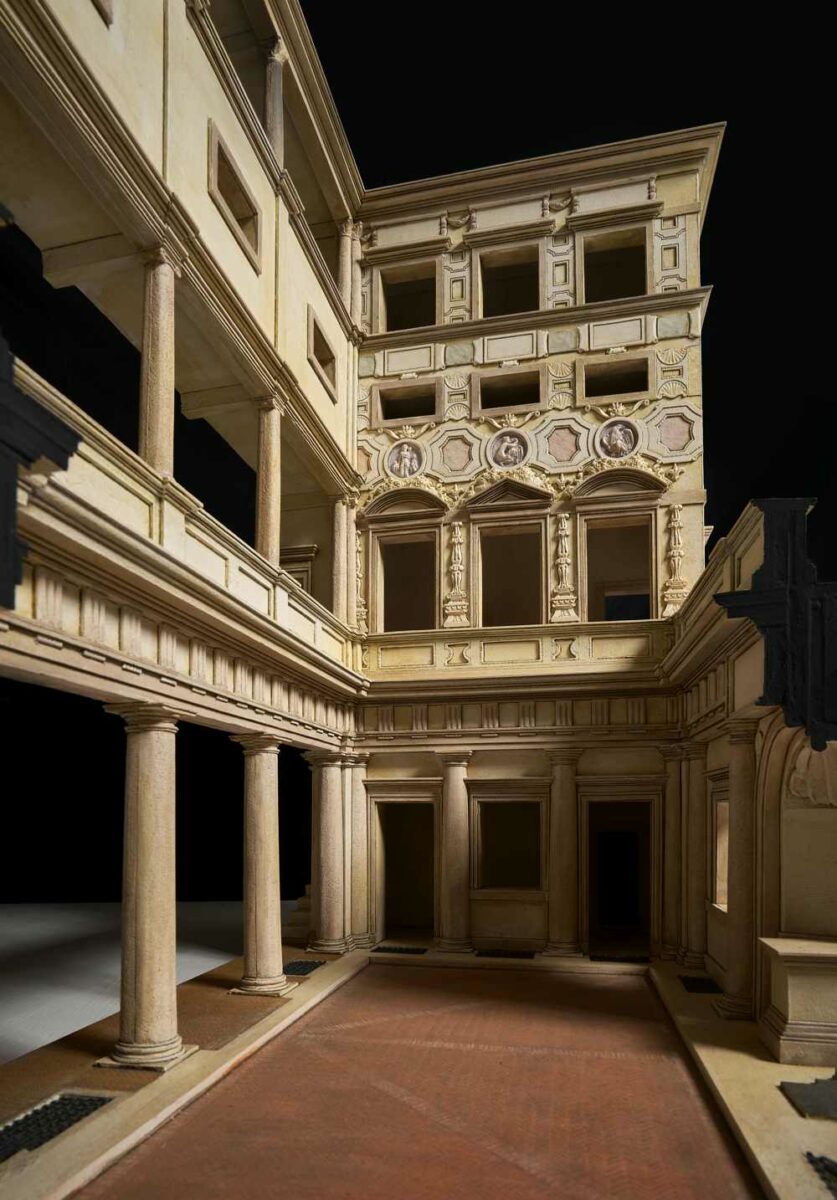

All these research methods and museographic strategies were evident in the room that was clearly the core of the exhibition, or at least the climax of its narrative: the one devoted to the late project for Palazzo Branconio, demolished in the mid-17th century. Often recognised in literature as the architectural masterpiece of Raphael, it had already been reconstructed by means of models in the past (for instance, in 2020, within the major exhibition organised in Rome to commemorate the fifth centennial of the artist’s death). However, none of these precedents managed to represent so vividly the sprezzatura, vitality, and lavishness of this lost piece of architecture. The ‘exploded view’ treatment of the model adopted in Vicenza allowed the gaze to follow the sophisticated distribution of spaces elaborated for this difficult site, and also used an innovative way of rendering the polychrome revetment of its composite façade, originally built with a combination of brickwork, stucco, limestone, and ancient marbles—a key feature of Raphael’s triumphal architecture, as visualised in the comparison with the Incendio di Borgo reproduced at large scale on its back. The catalogue texts often return to this project. Their approach ranges from detailed entries documenting the analytical philological work necessary to reconstruct the model from the available sources, such as the codex at Florence’s Biblioteca Nazionale, and the partial survey by Aristotele da Sangallo exhibited beside it, to the introductory essay by Nesselrath, which provides a new interpretation of its ancient models/prototypes, and that of Burns, which is entirely devoted to the social implications of this architectural enterprise. In the exhibition, an eloquent video introducing the maquette dwelled exactly on this aspect, visualising with admirable clarity the role played by the city’s topography, particularly the relationship with the Vatican Palaces, in the conception of this façade as a courtly demonstration of devotion and a form of self-representation.

Even more convincing than the other maquettes, this reproduction of Palazzo Branconio made graspable Raphael’s sensual approach to the design of spaces and surfaces, his understanding of architecture’s materiality, and his sophisticated assimilation of imperial antiquity. It also demonstrated how the work of reconstruction can be interpreted as a constructive tool of research, which can lead to unexpected results when employed with sufficient analytical rigour and made clear the challenges posed by models as a traditional tool of historiography and architectural practice. This aspect alone offers sufficient material for an entire exhibition: one that was certainly demanding for its audience in terms of modes of observation and degree of attention, but which gifted true moments of aesthetic and intellectual pleasure.

Guido Beltramini, Howard Burns, Arnold Nesselrath, Raffaello. Nato architetto was on show at the Palladio Museum, Vicenza, April 7–9 July 2023. A copy of the catalogue, in Italian, can be purchased here.

Dario Donetti is an architectural historian and Assistant Professor at the University of Verona, with appointments at Stanford University and the University of Chicago.