Shatwell Farm: Cars

This text is the first in a series of studies of Shatwell Farm made by Emily Priest while staying on site in September last year.

I first came to Shatwell Farm on a wintery November morning in 2022 to see the drawing archive with some friends. On arrival, Niall recommended we first walk the grounds and have a look around. Before driving off with his partner, Kendra, Niall described Shatwell as a working farm.

The grounds were entirely desolate. In the quiet, there were odd relics such as a fridge full of cider and shiny pinecone-looking decorations hanging from precast concrete gables inside one of the sheds. Were these from last Christmas or for the one coming? Apart from our group, and the cows, there was no one around and most of the enclosed areas of the farm were locked. Given how vacant it was, this term working was not altogether apparent and so remained of interest. I wrote to Niall a few weeks later and asked to come back; not to look in the archive, but at the farm.

I returned for a week almost a year after the initial visit, at the end of September. When I arrived, I found Niall in the Drawing Matter office. The office door was open, while the archive was closed and hidden by curtains made of woollen transit removal blankets hanging behind the door. I was given keys to the Container House and libraries before being introduced to everyone working there. I heard shrill sounds of timber being sawn from one of the barns behind us and persistent moos from the cows. Vehicles were parked in front of the archive, as well as haphazardly around the farm buildings. People were coming and going, bringing and taking, fixing and propping.

At the same time as my taxi, two people arrived to collect a drawing that was going to be shipped to California. In this setting, the archive now appeared as an anomaly. A thing really in and of itself. Something secret, even though it is so available online, and apparently, international. The farm, on the other hand, was non-precious, resourceful and very much working. Working with what’s there. Working on how to improve. Working out what to do next.

Cars

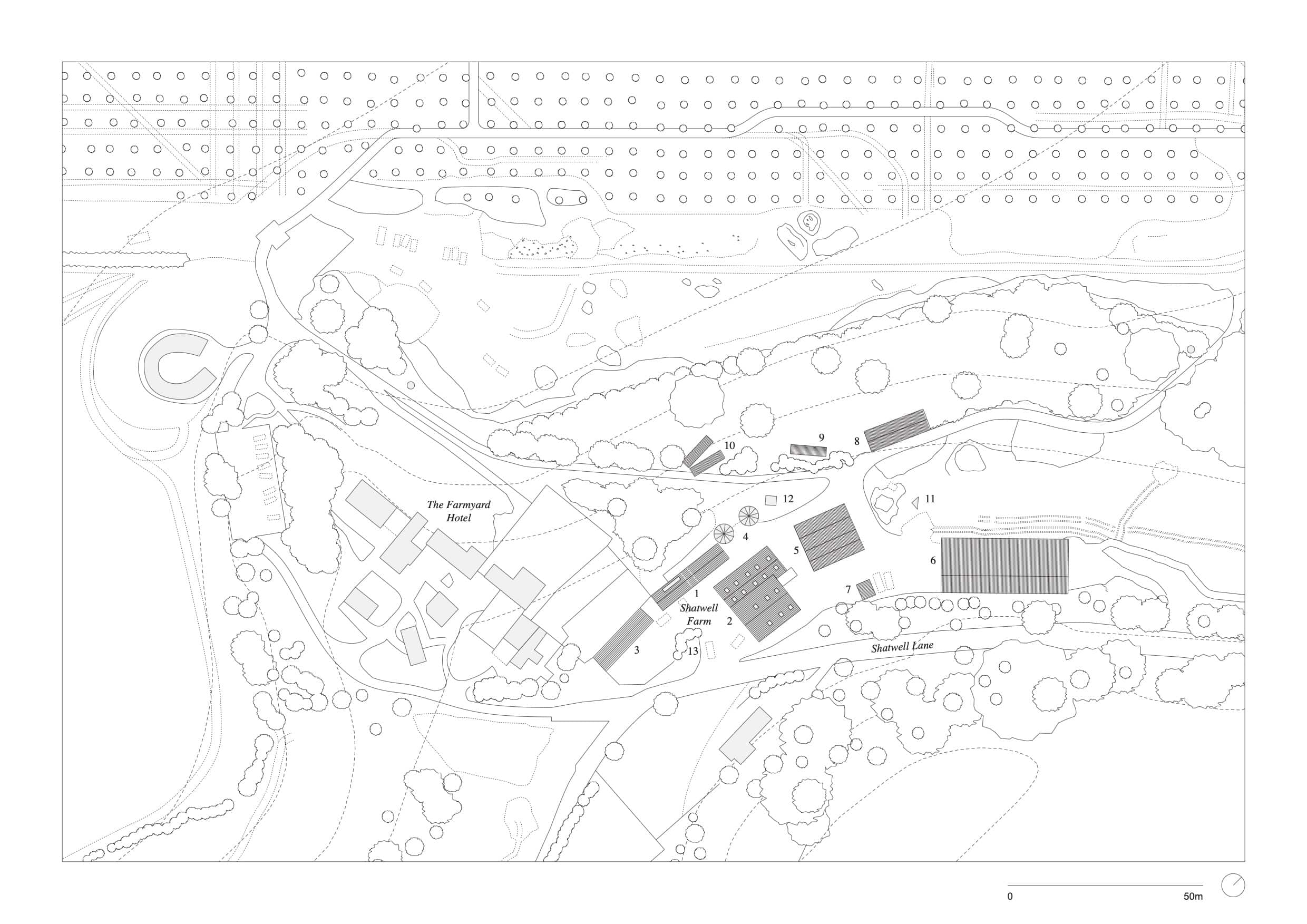

Shatwell Farm is accessed from Shatwell Lane which slips off from a busy A-road leading to Bruton. On entry, there is a forecourt, or yard, as termed by everyone on the farm. The yard’s perimeter is lined by the Drawing Matter archive and office buildings, and the Atcost barn. In the winter, the yard was empty apart from a typically white Ford transit van—the same one that can be seen in Max Creasy’s photographs from the book, Footnotes, backgrounds, sheds. This time the transit van, still in the same spot, was clustered with a Citroën and a Peugeot. Further up, there was a suitably hay-coloured Mondeo parked in front of the grain silos. This was David’s car, the farm’s handyman.

Despite being relatively inland, there was a boat parked down the track next to Shatwell Lane. Later on, in the north of the farm, I saw a DAF truck with faded John Lewis decals and a Mercedes lorry. The second of these had a colourful landscape graphic on its side that somehow matched the contour of the Yarlington Sleights behind the truck, south of the farm.

A Royal Mail van came twice in a working week and completed a full loop of the farm to deliver to each leased unit. This made the aggregation of uses and occupants more apparent, and the routes through Shatwell appear very much urban. What had previously been a dairy farm housing cows and horses, was now a site of multiple human occupants leasing the same buildings and structures for work that is not, for the most part, agricultural. I say for the most part, because of the cowshed, which keeps young cows before they go into the field. The cowshed is rented by a dairy farmer who visits the cows twice a day for feeding at around 11am and 5pm. The farmer came in a bottle green tractor pulling a Trioliet feed mixer. Excited for food, I tended to hear the cows before the farmer.

The people working on the farm told me that a fleet of McLarens had driven past from the neighbouring hotel on the morning I arrived. ‘The Farmyard’, is an offshoot of a large luxury hotel complex sited in Hadspen called ‘The Newt’. Buying up parcels of former agricultural and industrial land, The Newt describes itself as the ‘gateway to the west country […] Abuzz with agriculture and industry’ providing its visitors with ‘a thriving slice of English culture and countryside’. By culture, they may mean McClarens, but as for countryside, this seems to have left Somerset a while ago. The reality is that the types of vehicles now trailing these grounds have mostly graduated from tractors and trucks to luxury convertibles and compact hatchbacks. Increasingly, agriculture turns to tourism.

Emily Priest is an architect and writer from the UK West Midlands.

– Polly Gould