Simon Fraser University

This text is an excerpt from Arthur Erickson on Learning Systems, co-published by Concordia University Press and the Canadian Centre for Architecture where the Arthur Erickson Archive is held. The text is reproduced with the kind permission of the Estate of Arthur Erickson.

Recalling distant events is not easy, but those years two decades ago were momentous ones that changed my life, and certain experiences will always be vividly remembered.

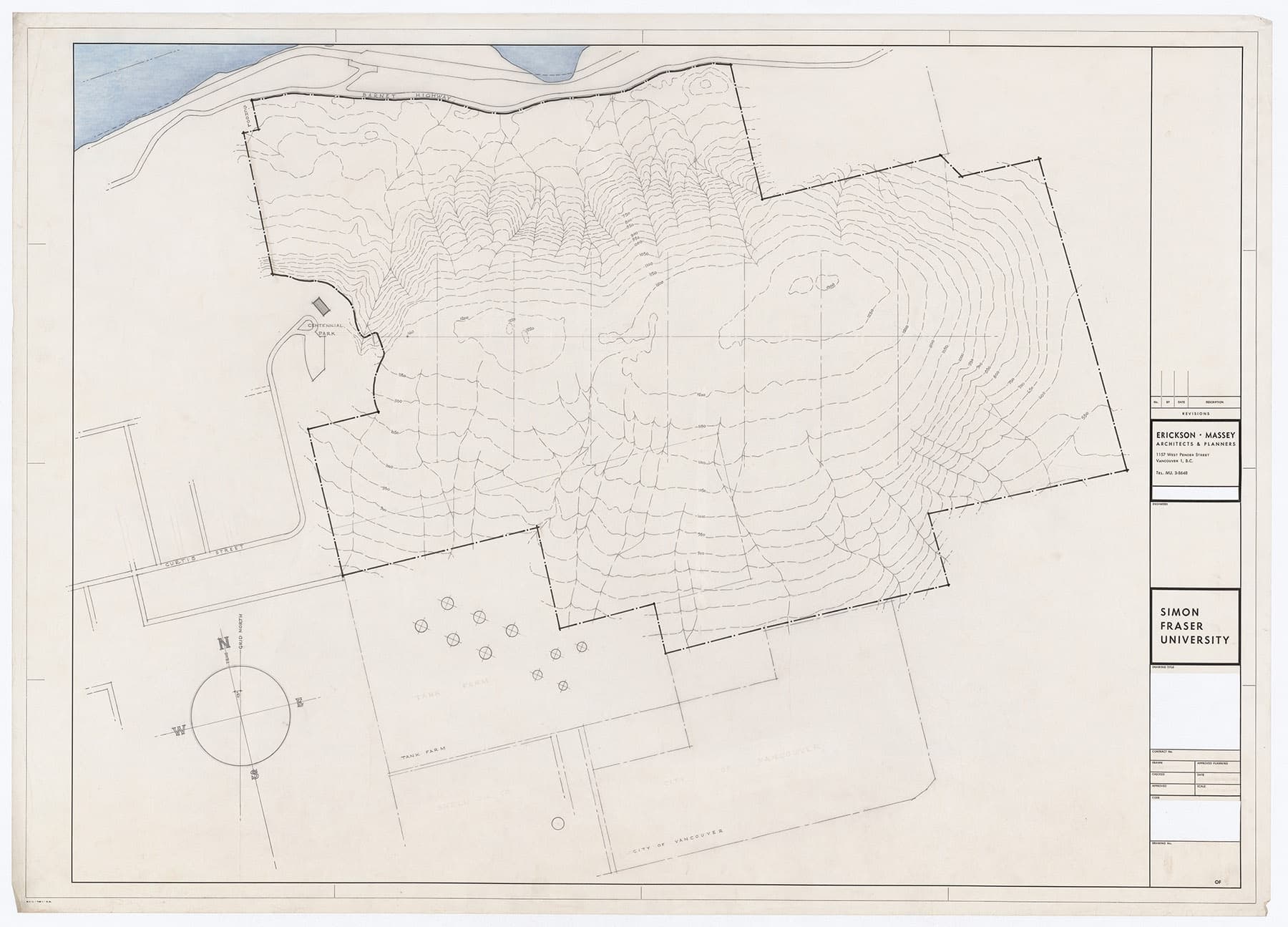

When the competition for Simon Fraser University was announced, I was an assistant professor at the School of Architecture at the University of British Columbia, keeping architectural skills alive doing a few small houses.[1] Conveniently, the competition would fill the summer break and finish by the beginning of the fall semester. I had no base to do the competition myself so I joined forces with Geoff Massey, a loyal friend with whom I had done a couple of houses. We augmented his staff at the New Design Gallery on Pender Street with the brightest of the graduating students and headed into the most frantic summer any of us had known.

The competition instructions had been very specific about the location of five buildings—an arts building, a science facility, library, theatre and gymnasium—as separate units on top of Burnaby Mountain. This requirement reflected the contemporary North American concept of the university as an umbrella for many specialized areas of knowledge, with faculties isolated in separate physical plants. To me, that concept existed for bureaucratic convenience rather than educational goals, and at the same time echoed Newton’s mechanistic view of knowledge rather than Einstein’s theory that all was connected.

I was more than an armchair skeptic about the evils of North American campuses. I had been teaching for several years. My thesis at McGill School of Architecture had dealt with New College, Oxford and the earliest universities. I planned after my graduation to visit them all: Al-Azhar, Salamanca, Paris, Oxford and Cambridge. They all seemed to embody a philosophy of education in which all knowledge was related and all its seekers—professors and youths alike—members of one community. Al-Azhar, with its tranquil courtyards and vast carpeted mosque where classes gathered almost informally about the muezzin, epitomized the intimacy of teacher and student. The Oxbridge colleges, with their purposeful, carved-out court spaces between dormitory and dining hall, and cloister connecting great hall and chapel, embodied a whole cycle involving equally intellectual, spiritual and physical pursuits.

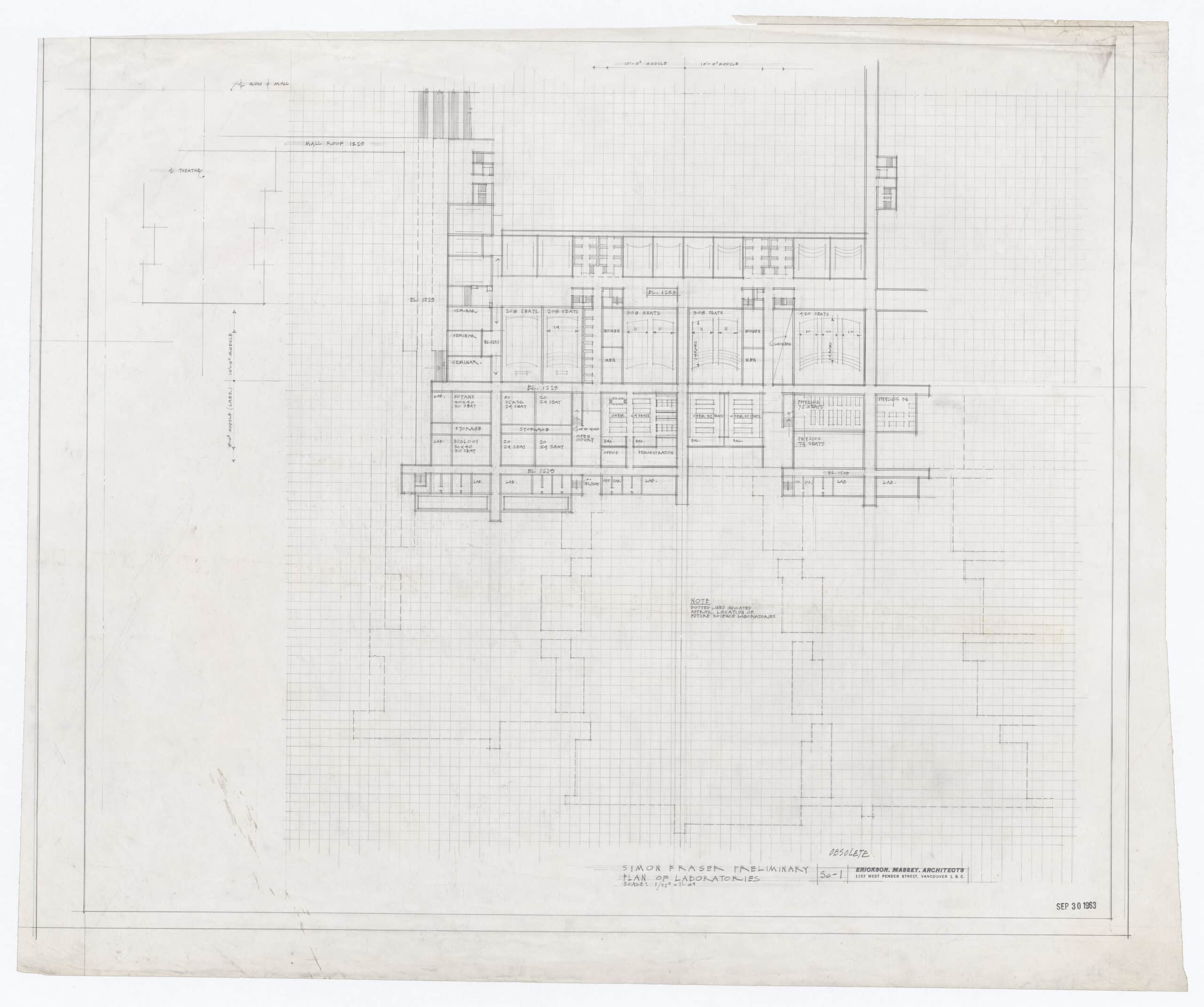

We began by looking at the common spatial denominators of all SFU’s faculties: auditoria, classrooms, seminar rooms, offices and laboratories. We saw that these need not be set up separately, but could be grouped in common, respecting administrative territories but taking advantage of economies in construction by mating like structures and services. This would automatically provide linkage of faculties and would encourage the growth and accommodation of the new disciplines then proliferating in the gaps between the traditional ones.

Approaching the problem of what form these new groups would take, I saw the opportunity to recreate the educational spaces so characteristic of the older universities. My own experience had taught me that knowledge was transferred as much outside the confines of the classroom as within. The right spaces would encourage those encounters. The mealtime discussion, the thoughtful stroll in the garden, the argument in the lounge—all this was seldom provided for in the utilitarian, force-feeding approach of the new universities of North America. We came up with four categories of educational spaces.

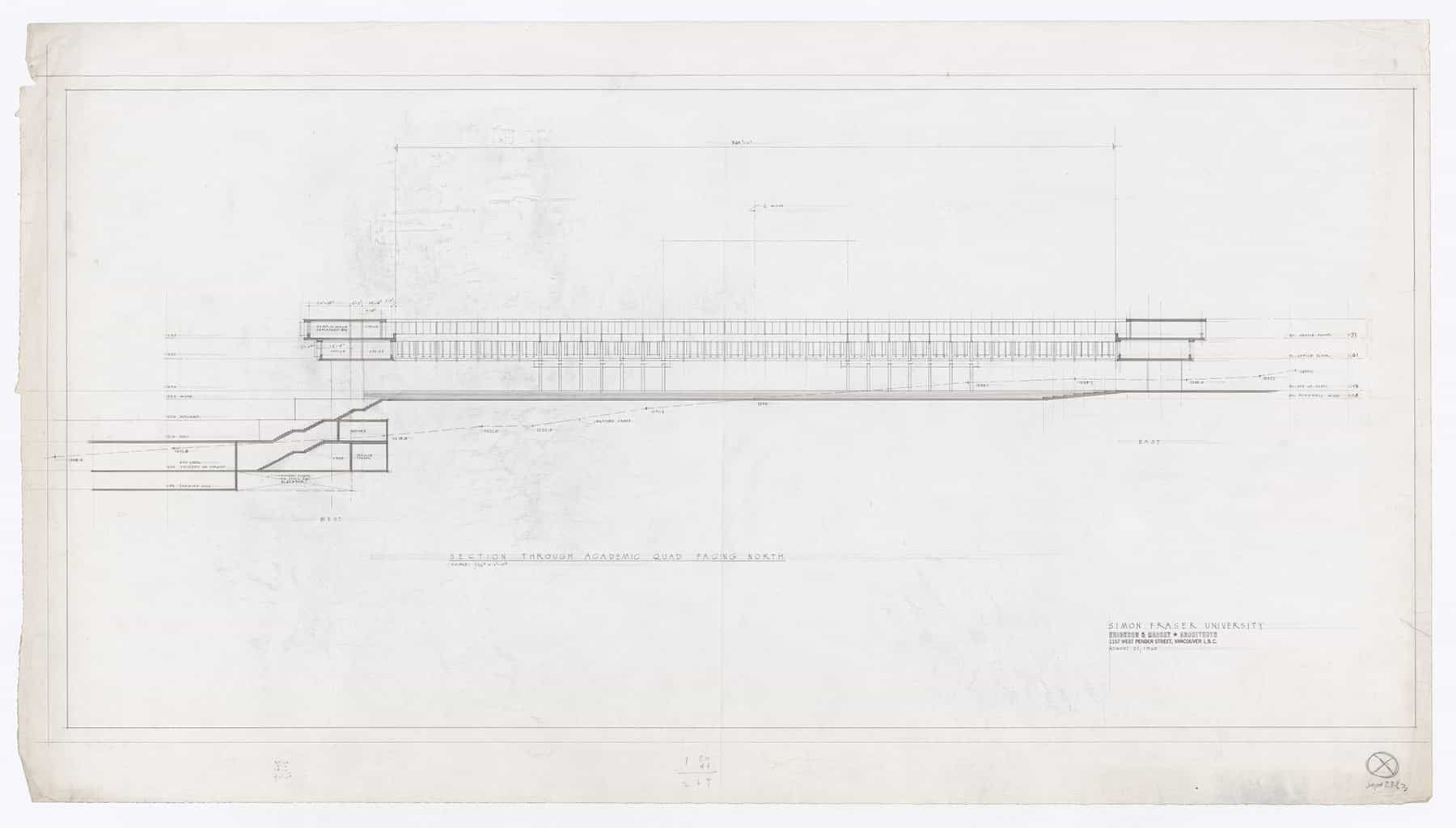

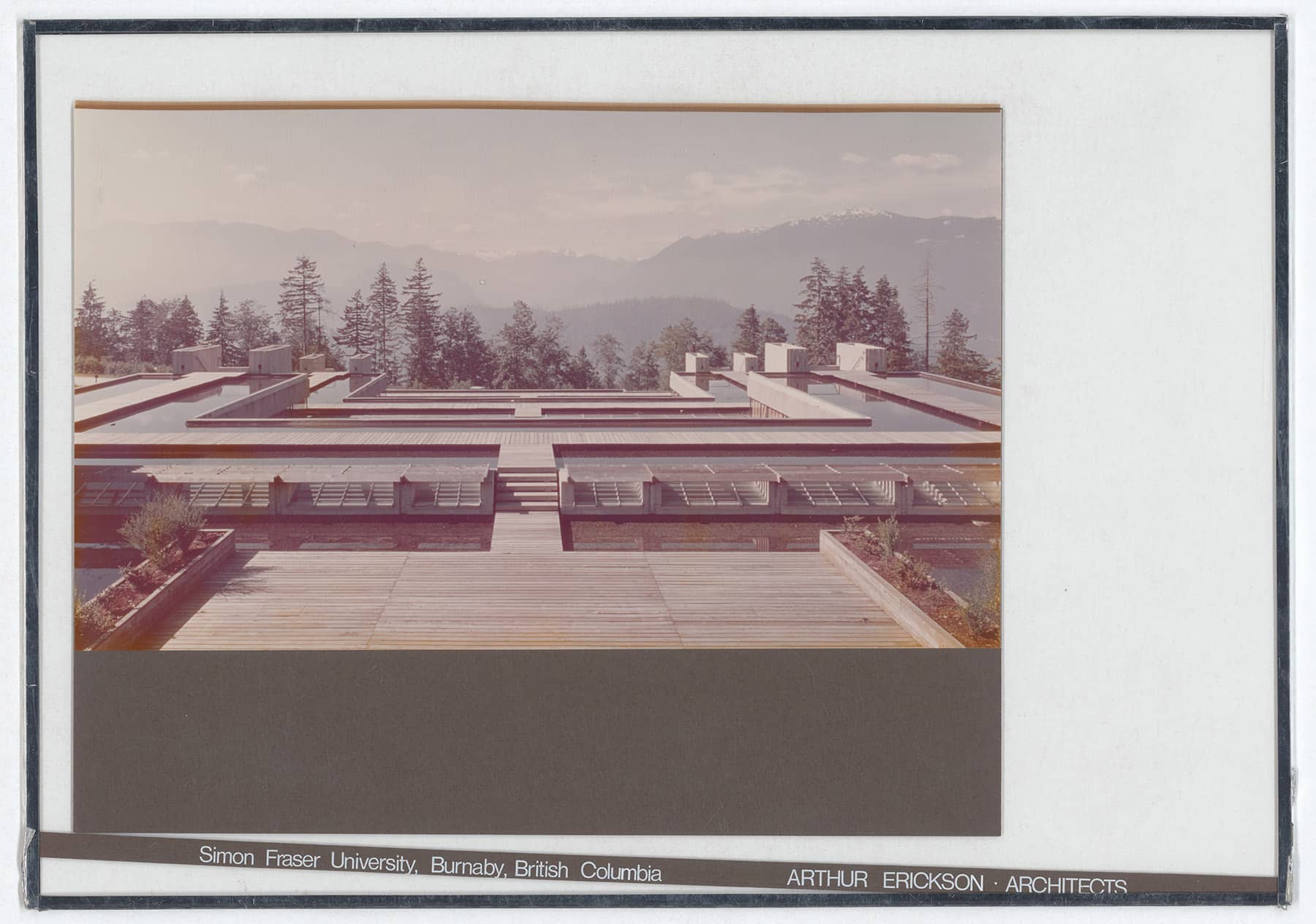

First of all, it was obvious that there needed to be a primary space at the crossroads of the university, the place of widest interaction between students adjacent to the library and eating facilities. Respecting Burnaby’s climate, this generated the idea for the covered Mall. The second space needed to be a counterpart to the Oxbridge quadrangle and would balance the busy Mall. The space would be tranquil, an area one could stroll in, talk and think—perambulation being recognized by both Buddhism and Christianity as conducive to deep thought. The mere preoccupation with repetitive movement in quiet circumstances frees the mind to probe and roam. Here was evoked the classic pattern of the monastery with its covered arcade of rhythmic repetition, its changing view of a garden and the sound of water. In our Academic Quadrangle there would be no variation in the monotonous pattern of windows and ‘fins.’ (I remember Zoltan Kiss bravely acquiescing to the bathroom windows being glazed, for the sake of consistency, in the same manner as office and seminar windows.)[2] If you walk slowly around the Quadrangle, see how the spaces change, opening up and closing down, glancing across a broad pool or compressing behind a berm or bosque of trees. Nothing should interrupt the serenity of the Quad.

The third space would allow for some raucous activity. It would be an alternative to the Mall, serving the sports complex, the student union and co-op, a cafe and a cinema. With 1,500 students projected, a second lively congregation area was necessary.

The fourth space was introduced into the program on our initiative. SFU was launched as a commuter school, but in my experience dormitory life was essential to the rounding out of one’s education and was, in any case, an essential component of all great universities. Thus, a residential complex to house one-third of the students was introduced next to the sports complex. We believed this position appropriate, for it could link both facilities and encourage off-hour use. Residences would be complemented by the unstructured and park like spaces at the far end of the campus.

My travels in the Far East demonstrated how even small buildings when cut into a mountain side could become part of the mountain whereas large ones perched on top were simply dwarfed by it. By terracing all elements of the university, its buildings, parking lots, playing fields and landscaping, the earth forms and structures could all become part of one composition—part of the mountain, not stuck on it. The plan also allowed for incremental expansion outward from a spine along the mountain ridge. The spine could connect all present and future buildings, bring services to them, provide parking and access from descending levels. The campus would be infinitely flexible and expandible. It was thoroughly rational and yet, properly respected, would never lose the beauty of being of one piece.

The day of the announcement of the result was bright and sunny.[3] An excited crowd had gathered at Burnaby Mountain Park. Geoff and I had given up hope of winning, for it seemed all we were suggesting was in violation of the rules of the competition. We had resigned ourselves to being right rather than winners and attended the ceremony out of curiosity about our colleagues’ work. You can’t imagine our utter astonishment when we were not only proclaimed winners but recommended as master planner and designers for the whole campus. The four runners-up would work on separate buildings within our plan and under our design guidance. The summer’s activity had been nothing—that September began the most exciting, frustrating and rewarding period of our lives.

We immediately asked Dr. Shrum for four months to reconsider our proposal in a more realistic light, for we knew how rash and romantic it was.[4] He replied, ‘I’ll give you one month and in that time, I will want a plan of how you divide the university so as to work with the four runners-up. Not only that, the university is to open two years from this date.’[5] We had no time to reconsider let alone question our premises for a task we thought from the beginning impossible. Our joy was dampened by the enormity of what we had to do. We didn’t know how or where to start. We were to put into concrete a university for which we had only an untested, wholly invented plan.

We were soon to become used to Dr. Shrum’s direct and uncompromising approach and to gain great respect for his clarity of vision, indomitable will and high principles. We had the idea and he made it happen. In fact, he had not been persuaded by our scheme at first, but once convinced by the jury, was solidly behind it. Though we were to tremble at many confrontations with him, he always gave us the support we needed and respected us for standing up to him. We were lucky, for the university would never have been built without him.

So the harrowing adventure was launched. I remember the exhilaration when, after the surveyors had cleared a line through the thick forest, we climbed stumps to look out and there at the end of the long swath we could see the green of Stanley Park and the Lion’s Gate Bridge, magically appearing just as we had predicted. With great enthusiasm, I wrote a prospectus on the idea of the university to be circulated for faculty recruitment.[6] I am afraid I misled many as to what could be realized in provincial British Columbia. Carried away by revolutionary zeal, I proposed a return to the tutorial system modified for vast numbers of students. Lectures would be few and to large groups, by distinguished professors, but the main teaching vehicle would be seminars of ten to twenty students. I remember the panic as we raced to get our thirty-second scale drawings done to hand over to our four fellow teams.

In the meeting at which we discussed the first phase building program, Dr. Shrum gave us some wise and prescient advice. ‘Do what is essential now,’ he said bluntly, ‘for there will be no opportunity in the future.’ So Bob Harrison was given the library; Duncan McNab the theatre, gym and swimming pool; Rhone and Iredale the laboratory component; Zoltan Kiss the first half of the Academic Quadrangle. As design coordinators, we chose not a building but the Mall structure that would tie the university together. It included a parking structure, a service trunk to all buildings and a landscaped bridge soaring over the ridges and dips of the mountain top. Certainly, it would never be built in a speculative future. Geoff and I had never done anything much larger than a single house and now we were immersed in the utter confusion of coordinating four architects and five contractors on five contiguous sites. As excavation progressed and foundations were poured it looked as though the whole mountaintop was being reconstructed. We managed by hiring the best people we could find and then bungled through in the fine old tradition.

We were well into the design development phase before President McTaggart-Cowan joined the university and the first faculty members were appointed.[7] The normal process of following the academic programming of the deans and their faculties was forgone altogether. In the rush, individual requirements were subordinated and the Chancellor and President made all the decisions about space allocations. The deans were left with choosing their furniture and equipment and fitting out their allocated space. But with only one man making all the decisions, things moved with great speed.

With the President came a Board of Governors and gradually decision-making became bureaucratized. Inevitably, no matter how sterling and well-intentioned the Board, matters were no longer as clearly and easily dispatched as before. We had hired a brilliant but unorthodox designer for the Mall roof.[8] While he had a persistent, unequivocable logic and professionalism in his approach, his manner antagonized the contractor of the Mall and undermined his credibility with the President and the Board.[9] As a result, he lost control of decisions that proved vital to the structure much later, in the great snow of 1973.[10]

I remember that everyone who worked on the university felt a sense of euphoria toward the end, exemplified by the Italian tile layers on the Mall. They would race down the Mall with forklifts swaying, singing Neapolitan opera in the mountain air at the top of their lungs. I had to reassure the President that they were not taking the job lightly and would be finished on time.

The university did open as scheduled. We thought that we had all performed the ‘miracle on Burnaby Mountain.’ Imperfect and unfinished, SFU could at least begin to function. We were justifiably proud of our ‘instant university’ and completely unprepared for a certain Board meeting at that time. We showed up expecting to be congratulated and instead found ourselves being roundly upbraided for defects in construction, leaks from hasty construction or where the work of two contractors came together, and so on. Afterwards, Geoff and I decided to drown our misery in a good film. Unfortunately, it was [Laurence] Olivier’s Hamlet and we stumbled out in even deeper despair! For the next few years we seemed to be working under a cloud, but construction continued, the Quad was completed and residences begun.

There was the difficulty in persuading the Chancellor to let us design the landscaping for the Quad, a responsibility I felt essential for realizing the Quad’s contemplative purpose. There was the Shell gas station crisis when, to our horror, the best site on the campus, plotted for the student-faculty union, was given over to a gas station. Gratifyingly, the first to recognize this abomination and react were the students who for weeks sported ‘Shell Out’ buttons.[11] There were the inevitable temporary huts—’Shrum’s slums’ that migrated from UBC and remain to this day. There was the threat of high-rise apartments to which we responded with a low-rise scheme that housed as many as cheaply, and conformed well with the campus. After we showed it to Dr. Shrum, the ‘developer’ disappeared.

There were the days of student unrest and an ‘occupation’ but I was confident that no damage would be done, for the very nature of the university plan defied riot.[12] There was no building that could be targeted as ‘theirs.’ Someone later suggested to me that the very urban nature of the campus defused violence, for everyone was crowded into a shared situation and forced to resolve their differences.

Very shortly, the academic record of SFU, though a small and new university, convinced me that the urban quality of the university was indeed stimulating cultural and intellectual activity. The university was a tightly compressed community, a city in miniature. The students that came out had left rural and suburban mildew behind for a more astute attitude towards life.

There came a period when we had little to do with the university at all, and the master plan was contravened. The Education Department went in beyond the Science Block instead of near the gymnasium and consequently the balancing link that would keep the library central to the campus was lost.[13] Everything began to be concentrated at one end instead of distributed more evenly on either side of the library and Mall. For various reasons morale declined, to be reflected in the lack of upkeep, the proliferation of defacing posters, and notices taped everywhere. But that time has passed.

Recently, new leadership has brought new enthusiasm. Everything is looking fresh and well-groomed, as if only just built. I was called back to consult on the master plan and have been involved in the one proposal I have, from the beginning, thought most vital for the university—a university village.[14] If the number of commuters could be reduced and a solid body of residents introduced, the university would gain a stability and liveliness that would enable it to offer a complete educational experience. Again, the model of Al-Azhar returns, where the ‘real life’ of the streets flowed just under the latticed windows of the dormitories. With the full university community’s endorsement and under the stewardship of Herb Auerbach, sketch plans were drawn up as a basis for development of a 2,160-unit village, to include shops, restaurants, hotel and conference centre, entertainment and recreation facilities. The village would be open for rental or lease, not only to students but to anyone wishing to live near the mountaintop university. University personnel would have priority but a mixture would be encouraged. At one point all necessary details were worked out and interested developers were even approached. It needed one small push from the Federal Government through the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation. But it was an unprecedented project that did not fall into a known category and so was easily tied up in red tape. For the university to come of age—for British Columbia to come of age—the village must be built, and in a way complimentary and supportive to the university. Only in this way will SFU move again towards a rendezvous with its destiny.

Long ago now, in the first spring of the university’s life, we were still unjaded and fighting for perfection. Our landscape plan would have the fields around the university planted in wild flowers and grasses, to slope down to a lake at the edge of the forget, giving a bucolic balance and retreat to the campus. But the groundskeeper kept cutting the grass. We became convinced that if we planted wild poppies there, the sight of their colourful blooms would keep the grass cutters away. Here was to be Flower Power in action.

One sunny late April evening, members of our office, several faculty, students and friends gathered about Helen Goodwin, a UBC dance teacher, on the slopes below the theatre. We had twenty pounds of poppy seed and several bottles of Faisca. To each person we gave a yard of red cotton to adorn themselves and a musical instrument, a simple percussion type. In the delicate spring air and splendid colours of the evening, we were overcome by a Bacchic exuberance. In a long procession, with strips of red flying from arms and legs and hair, we snaked and danced and twirled across the fields, around the running track, up the stairs to the Mall and down the Mall to the Quad. But for us, it was deserted. It was a truly pagan rite, and just as the sun was lowering Helen mounted the Quad steps like a high priestess. Each one of us, without bidding, came forward silently to lay our instrument at her feet as she invoked the setting sun.

(To see the existing Burnaby Campus map click here.)

At this point, some bewildered tourists wandered onto the Mall. What they saw, like the two spinsters at Versailles, were the ghosts of the original tribe that had built this mountain temple. Their shock was amusing at the time but now it seems that maybe, in reality, they had.[15]

Notes

- The architectural competition for the SFU campus was held in 1963, with the purpose of choosing one overall winner and four runners-up. Each runner-up would design a section of the university under the supervision of the winner. Erickson and Massey were awarded first place and the runners-up were Rhone and Iredale (William R. Rhone and W. Randle Iredale, second place); Zoltan Kiss (third); Robert F. Harrison (fourth); and Duncan S. McNab and Associates (fifth).

- Zoltan Kiss (1924–), one of the architects working with Erickson and Massey on the campus design, and responsible for designing and building the Academic Quadrangle.

- 31 July 1963.

- Gordon Shrum (1896–1985), the first Chancellor of SFU, from 1964 to 1968.

- The university opened on 9 September 1965.

- We have been unable to identify this document, however it seems likely that it would echo Erickson’s statements about education in this volume, as well as within the 1963 Erickson / Massey Architects planning document for Simon Fraser University.

- Patrick McTaggart-Cowan (1912–1997), the first president of SFU, from 1964 to 1968.

- Architect Jeffrey Lindsay (1924–1984), whose involvement with the campus design began in October 1963. Gene Waddell, The Design for Simon Fraser University and the Problems Accompanying Excellence (unpublished manuscript, 1998), 264. Simon Fraser University Archives, Item no. F-262-1-0-0-0-2.

- The contractor was John Laing & Son (Canada) Ltd.

- It seems likely that Erickson has misremembered the date, as the winter of 1968–69 saw the second-highest accumulated snowfall then on record. Referring to the Mall roof, Waddell writes, ‘in January and February 1969, unprecedented snowfall caused 45 percent of the glass to break.’ Gene Waddell, The Design for Simon Fraser University and the Problems Accompanying Excellence (unpublished manuscript, 1998) 304–6: Simon Fraser University Archives, Item no. F-262-1-0-0-0-2.

- These protests occurred in 1966. See Hugh Johnston, Radical Campus: Making Simon Fraser University (Toronto: Douglas and McIntyre, 2005), 257–65.

- Erickson appears to refer to a November 1968 protest over admissions policies regarding transfer credits where students occupied four floors of administration offices. See Johnston, Radical Campus, 284.

- The Education Building was constructed in 1978.

- Waddell writes: ‘In 1981 Erickson proposed a third ‘master plan for student housing … a mixed housing village carrying out the extended Mall but dissolving into a less formal village complex terracing down the slopes.’ Erickson said, “my whole aim was that it should be as much of a mixed community as possible” including open market housing. “I think the only thing that is missing which we put into our original scheme … was the village—that it [the University] should be a living community and not a commuting community.” In addition to proposing alternatives for housing, ‘there were also two updates of the Master Plan by Alan Bell from my office, one in the 70’s and the last in 1990 for a 25,000 student enrollment.’ None of these proposals resulted in any construction.’ See Waddell, The Design for Simon Fraser University, 364–5.

- A reference to the 1901 Moberly–Jourdain Incident, where two visitors to Versailles claimed they had seen eighteenth-century ghosts, Marie-Antoinette among them.