The Improvising Bouwmeester,* or: How Raymaekers’ Buildings Got Built

– Arne Vande Capelle, Stijn Colon, Lionel Devlieger and James Westcott

The following text first appeared in Arne Vande Capelle, Stijn Colon, Lionel Devlieger, and James Westcott, Ad Hoc Baroque: Marcel Raymaekers’ Salvage Architecture in Postwar Belgium (Brussels: Rotor, 2023), 168, 174-178.

*Master builder, from the middle ages, responsible for materials, design, construction, workforce, and client liaison.[1] Raymaekers rejected the modern diminution of the architect’s role, embracing instead on-site conversation, empowering his contractors, evading planning regulations, and mobilising his clients as salvagers and labourers, all the while seizing unforeseen design opportunities, whatever the consequences.

From 1965 to 1971, Raymaekers—who was unlicensed—collaborated with the architect Jos Witters. Besides drafting plans, Witters took charge of technical detailing (never one of Raymaekers’ talents), but they oversaw construction sites together. Witters’ expertise allowed Raymaekers to move away from the traditional architect’s role he’d played since the 1950s, and explore instead a new combined role of materials salesman and designer. In the mid-to-late 60s, Raymaekers began accumulating his first salvage stocks, initially in Drieslinter and later in Diepenbeek. He was also searching for ways to apply objets trouvés and other material experiments, fascinations he had developed during his art education, and was now translating to an architectural context. Early clients called him an ‘artistic salesman’, advising on materials that would fit the project and where they should be installed. This applied to the unique pieces that Raymaekers sold directly; but he also directed customers to nearby demolition sites for standard materials such as bricks and roof tiles.

In 1965, Raymaekers and Witters got involved in the construction of a new rehearsal and performance venue for the miners’ marching band Onder Ons in the small town of Koersel (Beringen), in the heart of Limburg’s coal country. During the entire project, no exterior contractor intervened. The original 19th Century venue was dismantled, and a new one—Feestzaal Onder Ons—erected on the same site, entirely by the members of Onder Ons themselves, many of whom were miners, the rest being masons. Members of the board facilitated the process: one of them, a contractor, lent his scaffolding; another was a mine director and provided access to the mine’s workshops. Many of the materials were salvaged from the original, dismantled venue (bricks, beams, some floor tiles); some came from various local demolition sites (mostly beams from barns); others were sourced by the miners themselves (like the stage curtain, from the local casino); and Raymaekers supplied materials as well (ship wood, steel, and zinc). The decision to build with old materials was common sense for the marching band and happened, according to the current president, who was then a teenager, ‘because it was cheaper, especially since we had so many craftsmen at hand.’[2]

Raymaekers was in his element in this informal context. Feestzaal Onder Ons was little more than a giant box with a sawtooth roof, built according to a simple plan provided by a local architect. Thus all Raymaekers’ energy could be focused on strategically integrating the reclaimed materials into the new whole. With the self-building miners and masons, he had a large body of workers at his disposal who were used to hard manual labor, solving problems on site through conversation, and able to adjust whenever a better idea presented itself. Since they were building for themselves, they were highly motivated, and best of all, their labor was free. The project took three years, from the dismantling of the original venue to the inauguration of the new one. Raymaekers used it to test his own flexibility, laying the foundations for his new practice with reclaimed materials.

Flexibility was essential for designing and building with salvaged materials, since they inevitably harboured far more unknown variables than new materials. Dimensions, quantities, performance, processability, treatments: with no manufacturer involved to specify and guarantee all these characteristics in advance, and no technical guidelines, the designer and the contractor were left to discover them, along with the possibilities and limitations they entailed, on-site. Raymaekers not only accepted all this as the precondition for working with old materials; he thrived on pushing the boundaries of those possibilities and limitations. It was the engine of his creativity.

The unpredictability of old materials liberated Raymaekers from the ‘torture devices’ that were drawing boards: it was impossible, and unnecessary, to work out an entire project in advance, which suited him perfectly.[3] The construction site became Raymaekers’ most important design tool. Here, with all the materials and elements ready at hand, the peculiarities of the site tangible, and the desires of the client (and his own) crystallising, he could perceive his projects as dynamic assemblages, drawing more on his art training than his period in architecture school.

[…]

Architects = bureaucrats

One figure notably absent in Raymaekers’ practice post-Witters was the licensed architect. He had little respect for their role, venting in interviews against what he called the ‘modern architect’ who was no more than a technician, a bureaucrat aware only of urban planning rules and technical standards, capable only of designing ‘chocolate box’ architecture defined by a ‘rational assembly of concrete geometric components.’[4] The architect’s main tool—two-dimensional plans and sections—created ‘rigid and static spaces.’[5] For Raymaekers, ‘the architect is no longer a creator.’[6]

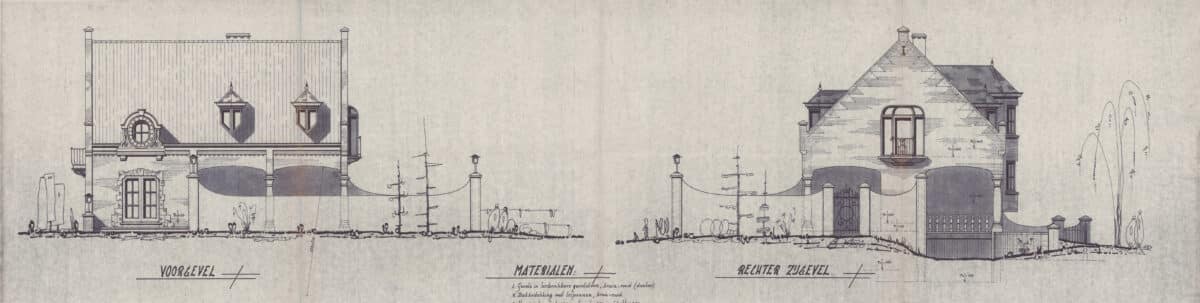

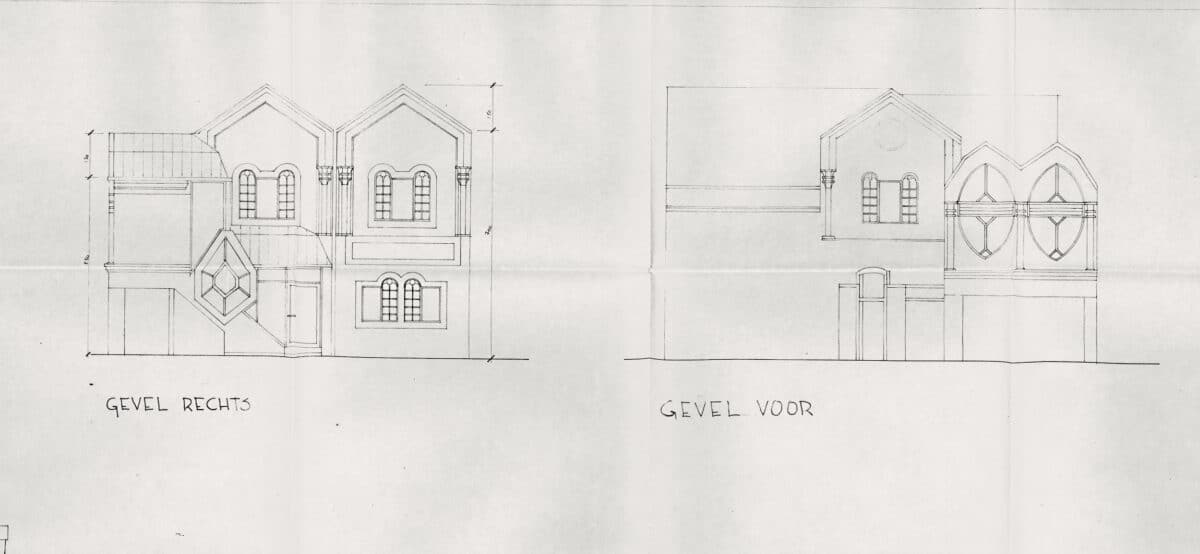

But Raymaekers was forced to enlist architects nonetheless, on account of Belgium’s 1939 law professionalising the discipline: building plans had to be drafted and signed by an architect, who needed to hold an accredited degree and be registered with the Order of Architects. Raymaekers did not meet either condition, meaning he was not allowed to sign the drawings required for planning applications, and could not take the necessary legal responsibility for the design and for construction site supervision. Raymaekers shrugged off this inconvenience, hiring numerous architects to draw the plans, sections, and elevations to obtain planning permission, based on his initial sketches or models (leaving crucial technical decisions to them).

As far as Raymaekers was concerned, the architect’s job was finished the moment they signed the drawings. From the 70’s onwards, after the breakup with Witters, he never bothered establishing a stable collaboration with any one architect. He simply instructed his clients to find an architect willing to do the drawing and signing. A few of them remained involved, assuming responsibility for what they had drawn and for the correct execution of the works. But most disappeared after signing. ‘Name loaning’ (naamlening)—signing a plan that wasn’t one’s own—was so common in Flanders that, between 1979 and 85, artist and architect Luc Deleu signed 150 planning application drawings by DIY-designers without any compensation. To avoid possible legal ramifications, he would systematically adapt the proportions of one room to the golden section as evidence of fulfilling his duties as an architect. With his Manifesto to the Order—addressed to the Order of Architects—Deleu questioned the architects’ monopoly over the design process, while at the same time calling attention to the absurdity of reducing an architect’s role to a signature, and called for agency to be returned to a building’s future occupants, who could, in many cases, do perfectly well without the architect. Other architects, like Simone and Lucien Kroll, organised participatory design projects, translating stakeholder input into the architecture of their buildings as loyally as possible. For La Mémé, a building complex for the UC Louvain Faculty of Medicine in Woluwe, the Krolls envolved students, local residents, and masons into the design and construction process, resulting in a deliberately heterogeneous, haphazard result.

Raymaekers differed from these contemporaries in that his resistance to the bureaucratic role of the architect was a means to an end. His search for a new architecture for the middle class was political, but his methodology pragmatic. It was only by using the construction site as a tool for design that Raymaekers could realise his idiosyncratic salvage architecture.

Confronting and evading planning applications

Raymaekers also applied his radical pragmatism to resolving the difficulties of planning applications. They were fundamentally problematic since they required a completely worked-out project before construction started, and that was not how Raymaekers worked. Detailed facade elevations were a particularly important part of the application package. Sometimes, Raymaekers submitted to protocol and designed the facade in advance, but still made last-minute changes on-site, exploiting unforeseen material and aesthetic opportunities, while keeping changes small enough not to ruffle feathers. Other times, he completely disregarded the facade specified in the planning application. Eliminating certain windows or elevating the entire building were frequent moves that fell somewhere between these two strategies.

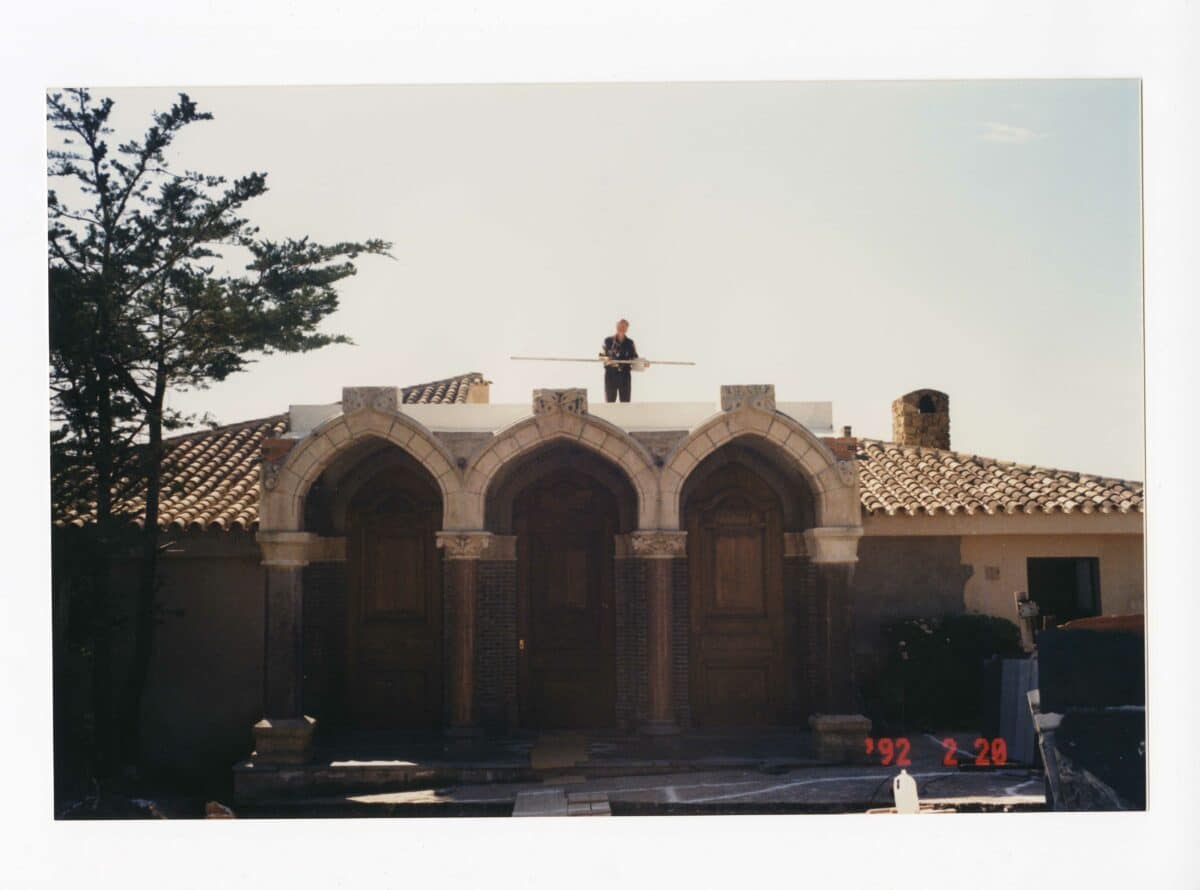

For the Valentijn flower shop, the facade design was based on a single batch of materials: the dismantled Art Nouveau facade of architect Joseph Bascourt’s own house, which arrived at Queen of the South on pallets. Without knowing or caring how the pieces were originally composed, Raymaekers shuffled them into a new configuration, measured up the result, and had it drawn up by the client’s architect. Using single batches of salvaged antique materials against a backdrop of reclaimed bricks was another recurring design strategy.

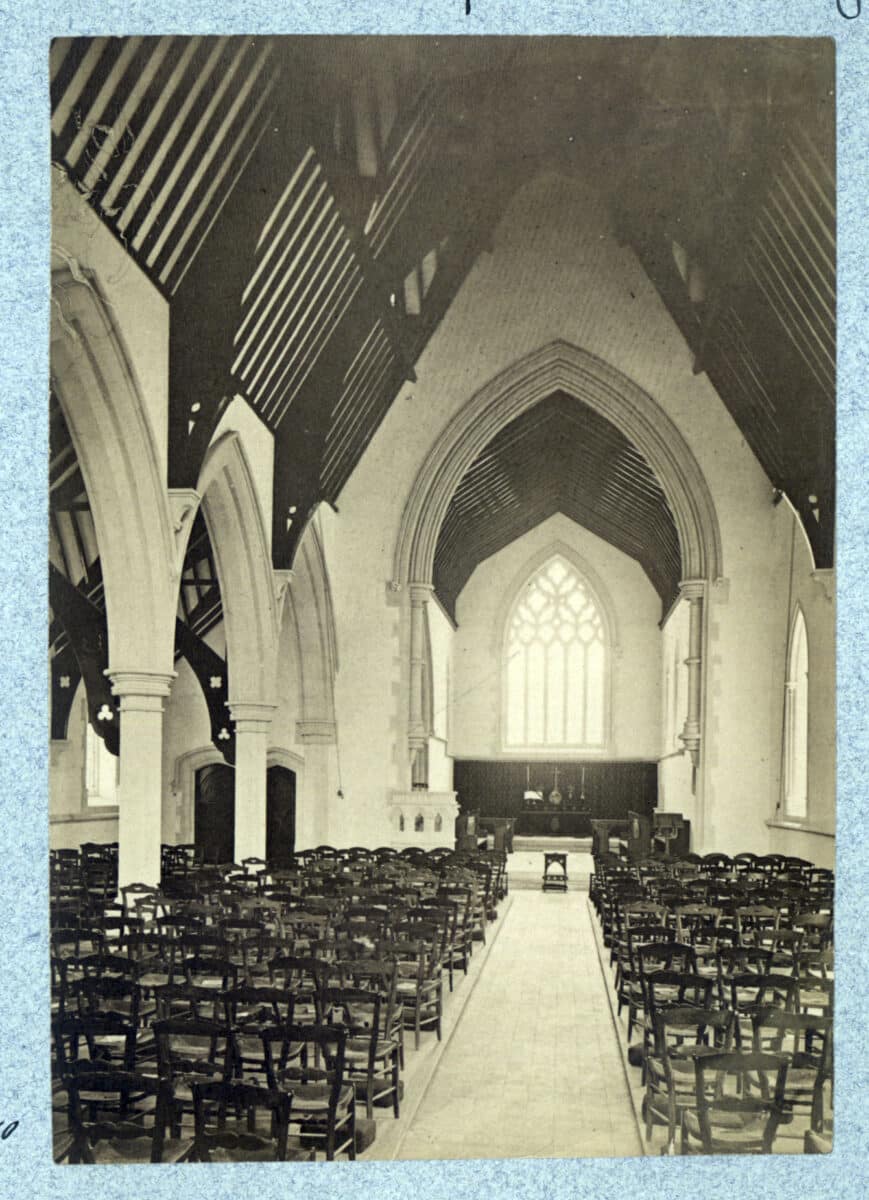

All of the natural stone facade elements for House Moffroid came from the Église anglaise in Spa, and those for House C’s facade came from a dismantled chateau close to Brussels. This tactic allowed Raymaekers to just about meet planning requirements, since elements were mostly known beforehand and could be committed to paper by the client’s official architect without losing too much time. The result was similar enough to the application to avoid upsetting planning officials. In any case, Raymaekers exploited the advantage of being ahead of the game: ‘Once a house was standing, nobody was going to come and tear it down.’[7]

Over the years, Raymaekers grew increasingly reckless in his adaptations and evasions of planning applications, and officials increasingly had problems with the houses emerging on his sites. The few architects who insisted on staying involved in the construction process were given a hard time by Raymaekers if they pointed out potential planning infringements. And when officials came knocking, Raymaekers often left it to his clients to deal with them, trusting in their negotiation skills – and their local political connections – to smooth things over.

In extreme cases, Raymaekers started redesigning essential features the moment planning permission was granted. For Queen of the South, he continued making changes at will over several decades. He accumulated at least seven official citations for planning infringements, but regarded these as little more than trophies for his contrary genius. For the P family, he was more strategic, instructing them to order an architect to copy the planning application from one of his previous projects, without ever having the intention of building it. After the long construction process was finished, they regularised the end result for a small fine they were more than happy to pay.[8]

Excursus: Rearranging the construction triangle

Raymaekers’ focus on materials as vectors of design fostered construction sites that were open and participatory places of production. His practice disregarded the key principle that had shaped the modern architectural profession: the division between thinking and making, legally formalised as the division between architect and contractor in most European countries since before the Second World War. Belgium’s 1939 law stipulated that ‘practicing the profession of architect is incompatible with that of public or private works contractor.’[9] The law reflected concerns around the potential for corruption in public building works. By dividing responsibilities, costs could be controlled and responsibilities pinpointed when things went astray. For private projects, the division protected the client, since the architect was responsible for keeping the contractor in check, and vice versa when the architect made unanticipated design changes and pressured the contractor to execute them at extra expense.

The triangle of client, architect, and contractor was initially intended as a tool of accountability and control. But it also entrenched the stratification between the players in a building project, a division that originated in the Renaissance. The expertise of the architect skewed towards abstract forms of knowledge like mathematics and geometry, gradually disconnecting from the material medium and the processes by which a building would be put up. The architectural drawing, originating as an on-site communication tool, gradually became the architect’s sole specialism. Design became immaterial, with an existence of its own, independent of its realisation. In parallel, the contractor became increasingly responsible for procuring materials, managing the building site and its workers, choosing the tools, and so on.[10] Over the course of the 20th Century, with its proliferation of laws, bureaucracy, and oversight, the division widened between architect and contractor, and between design and realisation.

By mobilising his clients as labourers, by trusting contractors to make structural, design, and detailing decisions in the moment, and by bundling the responsibilities of material procurement and design in his personal remit, Raymaekers created the conditions for returning agency to one of the actors that had been suppressed in modern construction: the building element. Raymaekers’ flexibility and compositional freedom, and the way he empowered all parties on the construction site, was not merely an idiosyncrasy of his; it was the essential requirement that made (his) architecture out of old materials feasible.

Raymaekers forged a role that was more akin to the bouwmeester (master builder) of the Middle Ages. For the more ambitious projects of the time, the commissioner maintained a single point of contact: the bouwmeester, who was both architect and contractor, responsible for the overall design, material procurement, and managing construction works, all of which were executed with a large degree of freedom and know-how by his personnel. Such a reciprocal and integrated approach made massive, intricate projects possible, and enabled adaptations to changing circumstances on-site—a process often continuing for generations.

With his folding together of professional roles, Raymaekers represents an understudied, divergent tendency in the modern history of the profession, where design and construction never grew apart to such an extent.[11] It’s most well-studied practitioner in the 20th Century is probably Fernand Pouillon, who designed and constructed immense buildings in natural stone in Europe and North Africa from the 1940s to the 60s, for a price that could out-compete concrete, widely hyped for its supposed efficiency. Pouillon did so by integrating—practically and financially—the entire chain of production, from the quarrying of the stones to their final installation. He was architect, developer, and contractor rolled into one. Unlike Raymaekers, Pouillon built social housing and received grand public commissions, so he naturally came under far greater scrutiny. In 1961, he was arrested and imprisoned, charged with fraud for selfdealing through his development company, Le Comptoir National du Logement. The extent to which Pouillon himself knowingly misused corporate assets (abus de biens sociaux) remains unclear.[12] But, even before the verdict was passed, he was kicked out of the French Order of Architects, which didn’t tolerate its members mixing the role of architect with other professions. Pouillon, constructing as cheaply as he did with stone, would be persona non grata in professional circles for over a decade, nor was he highly regarded by modern architects.[13]

These histories have a lot to teach us about the fictions and constructs of modernism. The breadth of Raymaekers’ oeuvre demonstrates how much Belgian constructive traditions were still capable of absorbing, in one way or another, unconventional practices as late as the second half of the 20th Century.

Improbably, Raymaekers demonstrated that the flattening carried out by modernism and modernisation—aesthetically, logistically, and professionally—was not total, despite appearances otherwise.

Notes

- In 21st-century Belgium, the bouwmeester is also a regional or municipal official in charge of organising public competitions and overseeing the architectural and spatial quality of large-scale projects.

- L. Smolders, interview with the authors, June 29, 2022, Beringen.

- ‘Ik ben kleuter gebleven, spelend met mijn blokkendoos,’ (I remained a toddler, playing with my box of blocks), Week/uit: Cobouw, April 24, 1981.

- ‘Ik ben kleuter gebleven,’ 1981.

- ‘De bouwende dromer,’ (The building dreamer) Elegance Architectuur, September 1980.

- Raymonde Musch, ‘Wonen op een puinhoop: Uitstalraam van een passie,’ De Morgen: Extra Wonen, May 19, 1990.

- One of Raymaekers’ favorite bon mots. Interview with the authors, June 16, 2022, Genk.

- BEF 18,000, or just over EUR 800, inflation factored in.

- Art. 6. (Translation by the authors.) The architect’s independence is essential in this formulation. Subsequent regulations (adopted by the National Council of the Order of Architects, Art. 10 and 11, December 16, 1983) stated that architects may not carry out acts incompatible with the profession, leaving the sourcing of building materials in a grey zone.

- Spiro Kostoff, The Architect: History of a Profession (NewYork: Oxford University Press, 1977).

- Michael Ghyoot and Cécile Guichard, ‘Les effets du réemploi sur la conception et vice versa,’ in Réemploi, architecture et construction: Méthodes, ressources, conception, mise en œuvre, ed. Pierre Belli-Riz (Antony Cedex: Editions du Moniteur, 2022).

- This is less the case for his collaborators at the head of the firm, their guilt has been proven. See Bernard Marrey, Fernand Pouillon, l’homme à abattre (Paris: Linteau, 2010).

- Later on, Pouillon was rehabilitated, re-joining The Order of Architects in 1978, and receiving the Légion d’Honneur in 1985.