Walter Segal, Self-Built Architect (2021) – Review

Given that architect Walter Segal was a Jewish immigrant, born in Berlin to Romanian parents, and a bit of a nomad, it seems unlikely that his best-known work would be confined entirely within London’s boroughs. Resident in the UK for perhaps longer than he had intended, it is in some ways incongruous that Segal’s legacy is defined by the way in which he helped others put down roots by supporting them to build their own homes. Such projects, always undertaken in collaboration, have become synonymous with Segal’s reputation as a prolific house builder, a job he took incredibly seriously, remarking that ‘the old truth still holds that nothing is so difficult to design as a good house’. These modest timber constructions, however, are a small proportion of, and perhaps culmination of, a life immersed in the cultural and political roots of large-scale and far reaching projects of European modernism, with Bruno Taut, Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier among Segal’s early influences (which he at times tried to distance himself from), as this comprehensive biography of the architect’s life details.

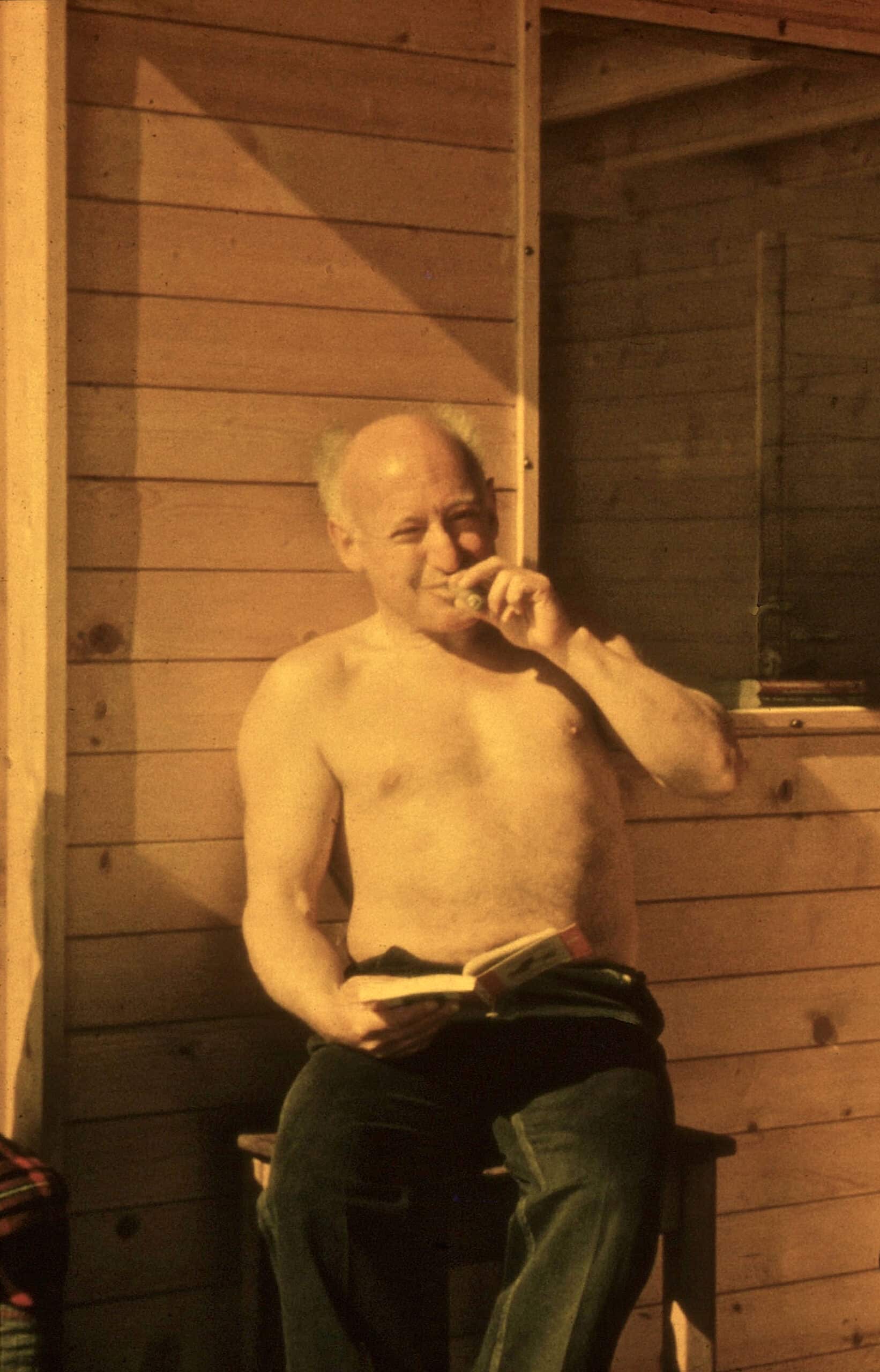

Alice Grahame and John McKean’s book, Walter Segal, Self-Built Architect, as the title suggests, highlights Segal’s self-build expertise but also his role as the progenitor of an unusual career, constructed on his own terms. Presenting Segal’s childhood and early job opportunities through a series of essays that focus on his family’s poor but culturally rich artistic life in Switzerland, the book describes Segal’s evident lifelong desire to be an agitator; taking pride in his reputation for occupying the margins, while simultaneously holding a teaching position at the Architectural Association, well connected and hardly ever in need of work.

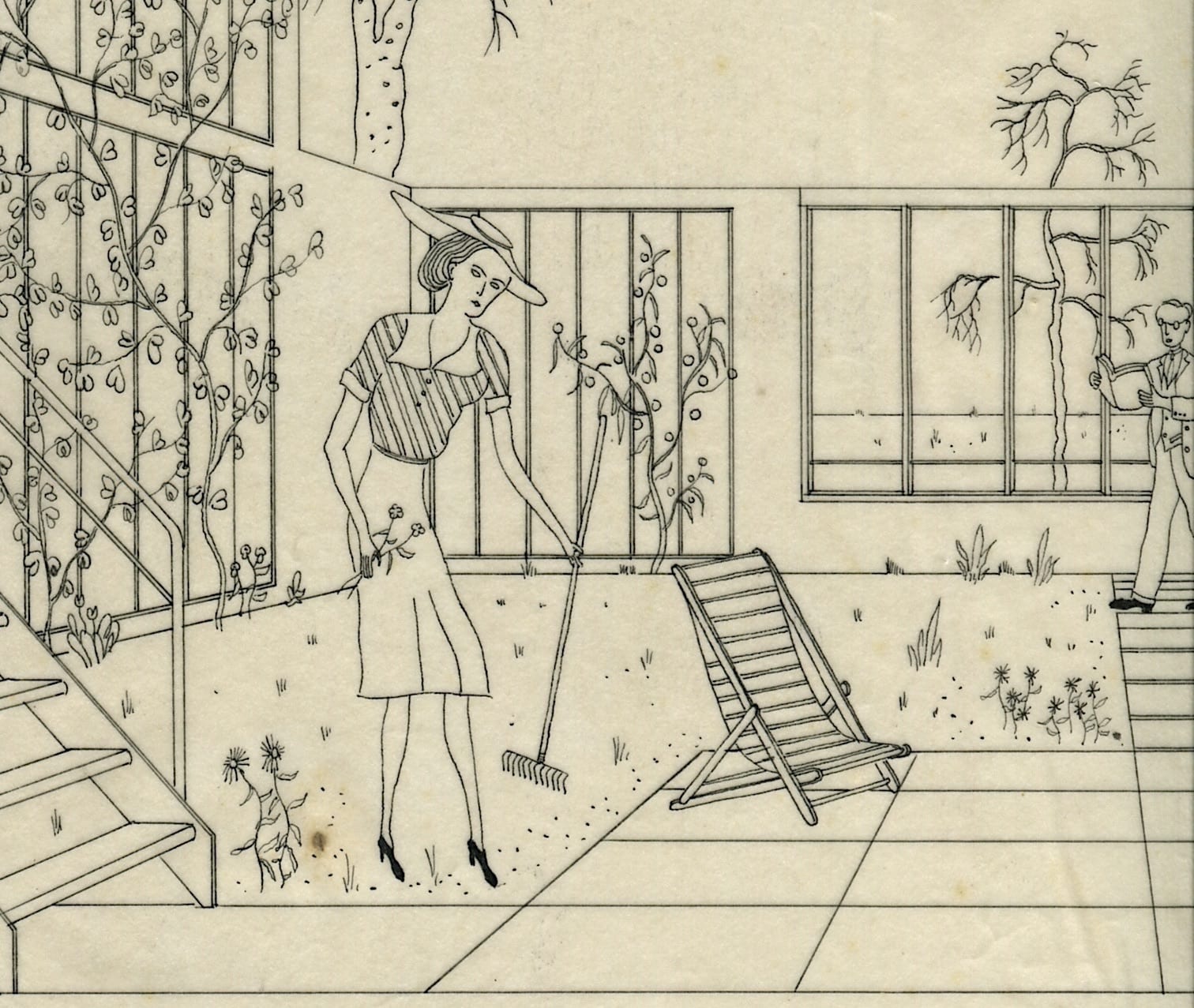

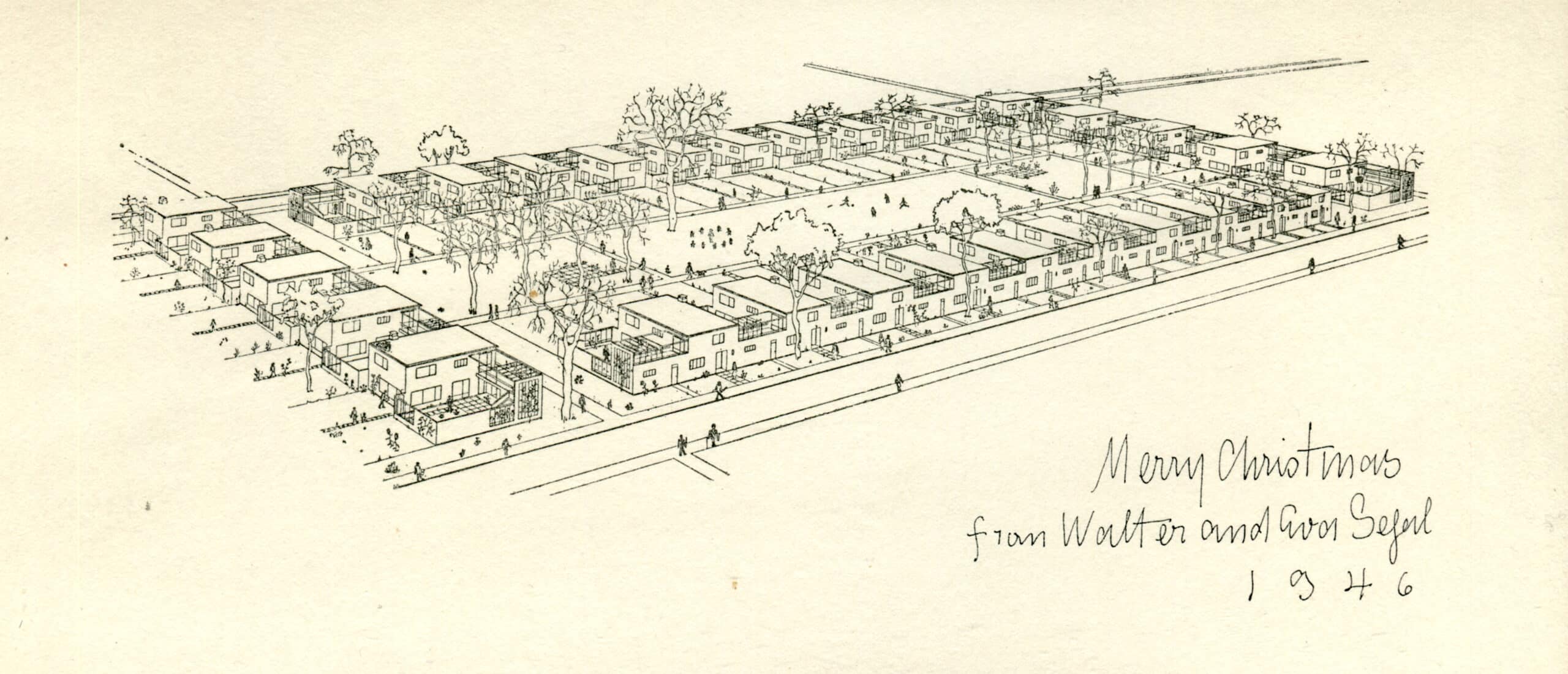

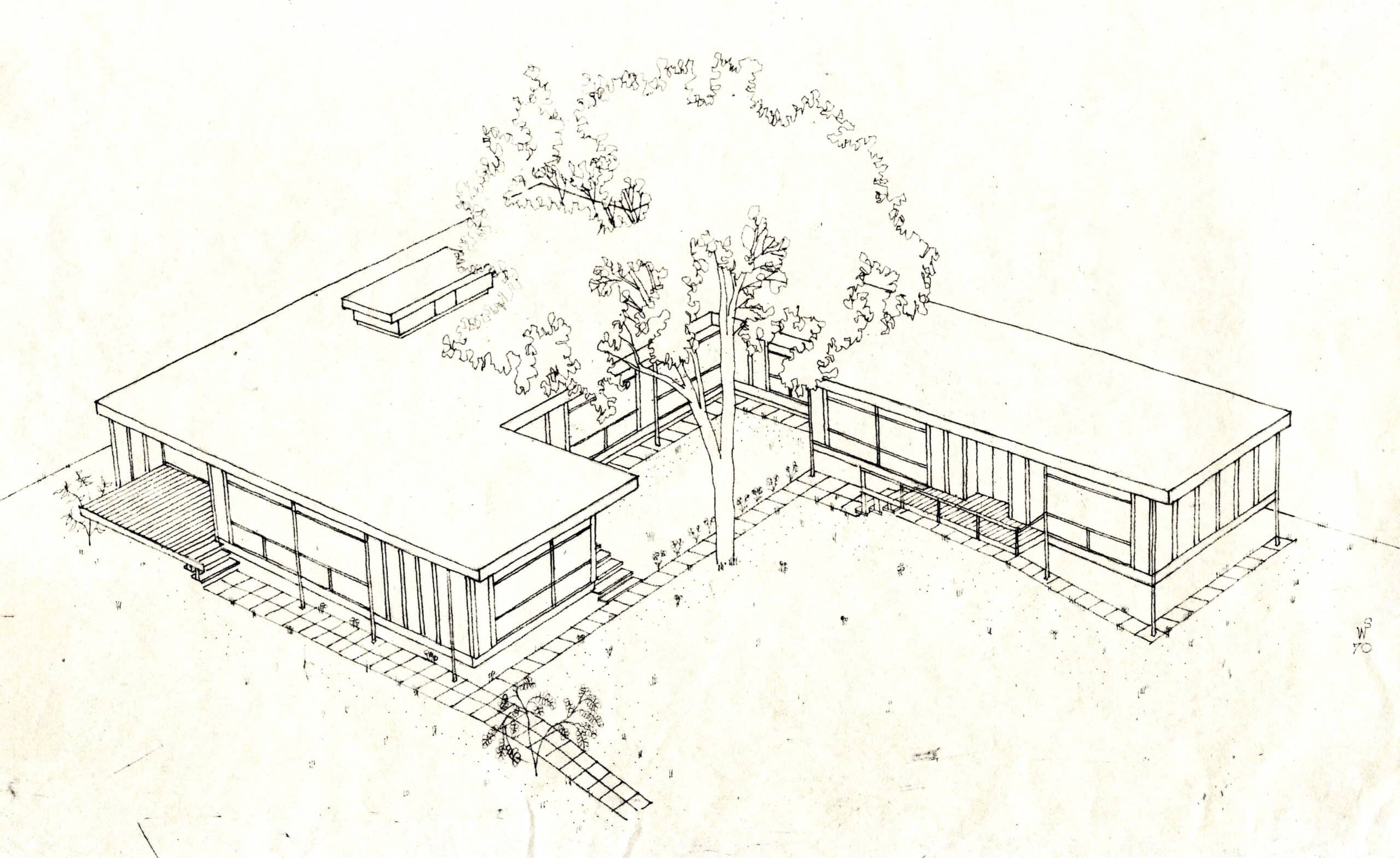

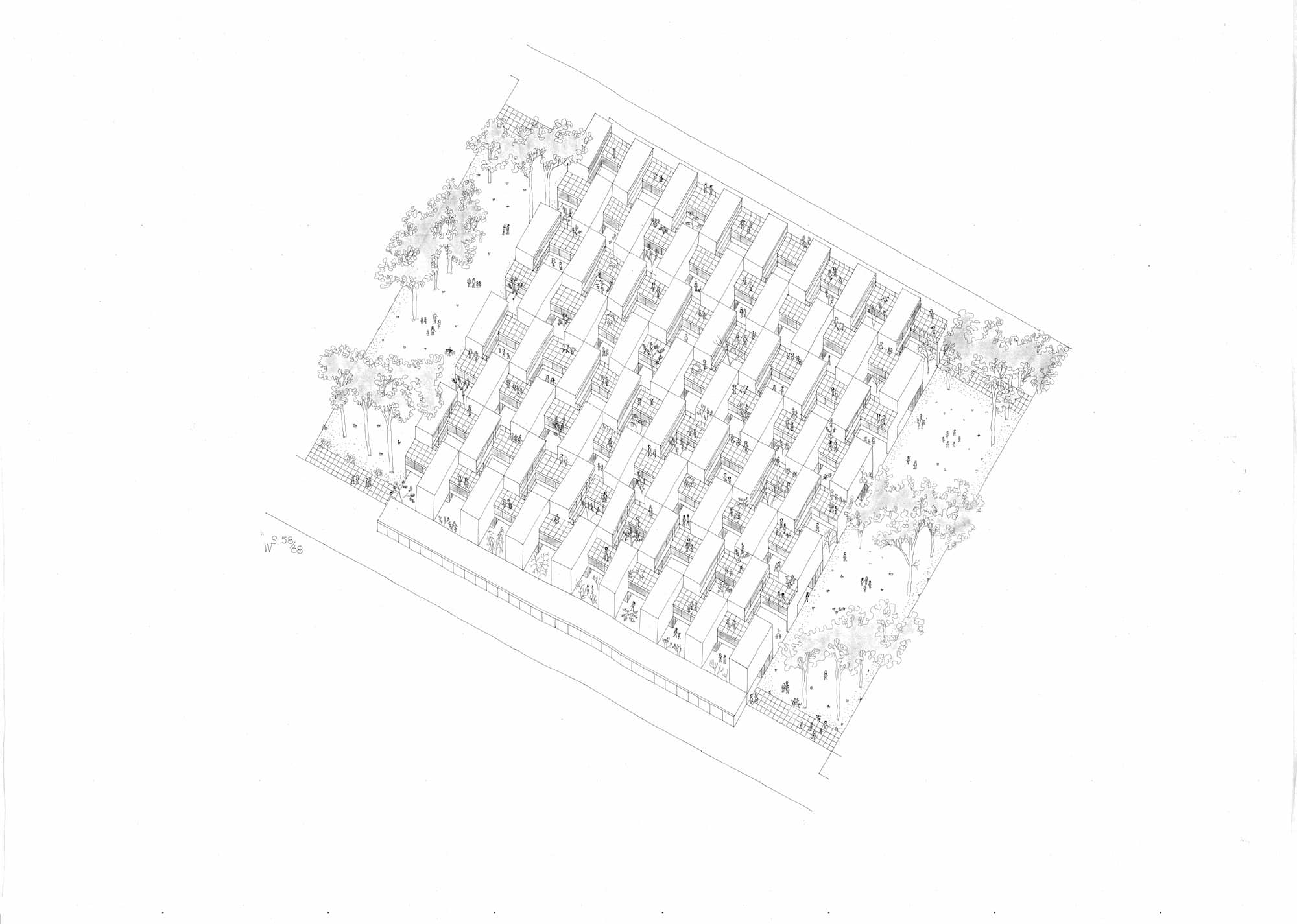

It may be shocking to collectively motivated self-build fans of Segal to read that he professed, with frequency, a desire to retain for himself full control of a project, effusively stating his rejection of authority. An early interest in timber structures, delivering small buildings utilising balloon frame construction across the Mediterranean, developed into a methodology steeped in his preference for knowledge and proximity to craft practice. He worked directly with builders, while equally negotiating adeptly with the technocrats of local government, often tasked with the delivery of buildings, as he implored, ‘it was easier to cope with the planning officer than with my wife.’

It is evident that Segal revelled in the production of meticulous drawings, of which the book contains many, belying the presumption that participatory forms of construction, including projects like Walter’s Way in Lewisham, somehow materialise orally and effortlessly. Now well established, the Segal Method has been adopted by many of Segal’s collaborators, and continues to operate in his absence. It is fitting that the latter part of the book creates a portrait of Segal by those who worked closely with him, architects and house builders alike showing the reciprocal social and empowering nature of sawing through a piece of wood oneself. What is conveyed is Segal’s capacity for humour and joy gained from a job well done, eager to please yet not afraid to ostracise those he worked with, is revealed by the obvious affection that the majority express.

Growing up in Lewisham, attending school adjacent to Greenstreet Hill: 11 units built in 1993 using Segal’s construction method, it seemed obvious to me that architecture should be about physical, hands-on and collective making processes. Despite Segal’s buildings being so prominent in my own day-to-day life, the architect remained largely a mystery as I pursued professional training at university, finding myself decoupled from any on-site experience. Segal, having passed away in 1985, represented a distant past that has been irrevocably changed by Thatcher’s neoliberalism, which gave rise to computer-aided parametricism popularised in the early 00s that today benefits a developer-led, privatised housing market. Grahame and McKean’s book presents a modern alternative, revealing something of Segal’s life without giving the game away; contextualising his intellectual inheritance framed by a comprehensive description of buildings and crucially, how to build them, recuperating twentieth-century ideas in the face of twenty-first century housing need. As a man, Segal is tantalisingly kept out of reach while his architecture is viscerally represented, the reader cajoled into believing that they too can do it all themselves.

Alice Grahame and John McKean Walter Segal, Self-Built Architect (2021) is published by Lund Humphries. Copies of the publication can be purchased here.

Jane Hall is a founding member of Assemble. Her current projects include: The Dreamachine across the UK during the summer of 2022 and The Place We Imagine: Lina Bo Bardi at Nottingham Contemporary until 4 September 2022.