Stendhal’s Autobiography: La Vie de Henri Brulard

Soft childish snow swirled on the sidewalk in New York. Lecture given, Christmas presents bought, two hours before the bus to Newark. Outside a bookstore a stall of paperbacks to clear, and there it is, the New York Review of Books’ paperback edition of La Vie du Henri Brulard, Stendhal’s autobiography of his own youth.

It is the model for Tommaso di Lampedusa’s memoir of childhood, Places of Infancy, and is paraphrased by Sebald in Vertigo. I’d always been curious to read it. But, first, Lampedusa advises that no one under the age of forty can read Stendhal. Forty? Tick. Second, Stendhal’s deity was of nonchalance and spontaneity. You can’t go looking for La Vie online. It must just happen. At the till the cashier shrieks: ‘That book is a block of ice!’

In a corner bar (New York does corners, London does not) early Bruce Springsteen plays. For two hours, and with two dusty glass cups of Rioja, I am inside a stranger’s childhood in Grenoble.

La Vie ends when Stendhal is seventeen, riding into Milan in 1800 in the army of Napoleon, and the narrative intercut with flashes of adult loves and quarrels. But it begins on Rome’s Janiculum Hill, as Stendhal faces the ancient view. ‘I am going to be fifty, it’s high time I knew myself. What have I been? What am I? The truth is, I’d be very hard put to say’.

But that beginning is a cheat. He did not begin the book in Rome in 1832 but in Civitavecchia in 1835, when he was 53 and serving as a French Consul at the port. Stendhal was one of the thirty-plus pseudonyms of a real name scratched on a wall in Grenoble: Henri Beyle / 1789. But — you guessed it — the wall is gone.

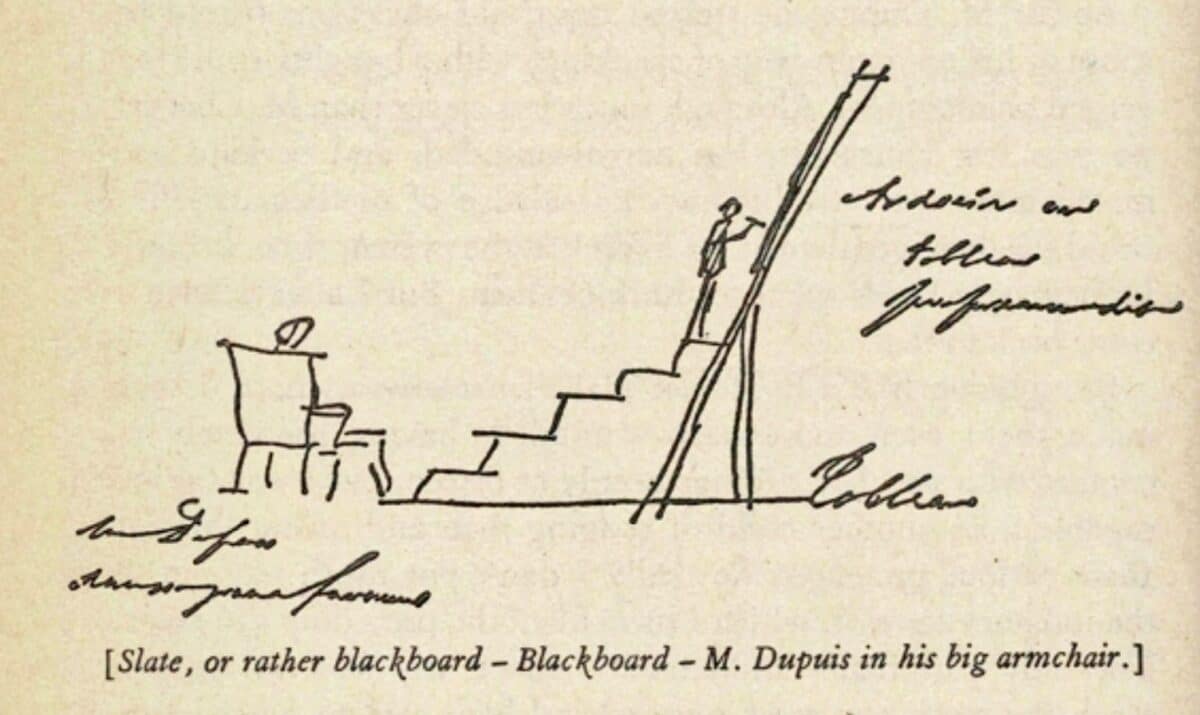

La Vie is the first modern autobiography. Stendhal puzzles over his own fractured identity, lists every criticism of his character ever recorded and accepts that others’ perceptions of you are part of yourself. He refuses to tell us the stories we want: dinner with Byron, or the retreat from Moscow (the only reference to which is his successful transport of the manuscript of an unsuccessful play). It is plain hard work for many chapters, as he lists schoolmates’ faults or the shopkeepers’ rivalries of Grenoble, and adds strange plans drawn from memory of the arrangement of the room in his grandfather’s house, or of the streets between home and school. All the time he paces the cold little room in Civitavecchia.

The energy in his fugitive sense of the past is like a fresco, intact in parts, crumbling in others (his analogy). Autobiography as self-excavation is in contrast to autobiography as dictated epitaph, like his bête noire Rousseau (or a modern politician) knew exactly what he wanted to tell you before he began to write. Stendhal is his own audience: ‘I am making big discoveries about myself as I write these memoirs’.

There are three phases of self-discovery. The first is that he has not changed, writing ‘I am still in 1835 the man of 1794’ when he remembers his happiness at the news of the execution of Louis XVI. Then he begins to note changes in himself: he no longer shoots wild animals, for example. But there are harder realisations: that winter in Civitavecchia he took himself to pieces. And stared without self-pity.

But then he puts himself back together again. By that brutality and bravery to self he, at the age of 53, unlocked a new life for himself. The man of 1835 is not the same as the boy of 1794, he learned: not, at least, in terms of outward statements or actions. But there is a deeper continuity: he has remained true to the virtues of his youth. Which are? Nonchalance, Napoleon, understatement (at fifteen, he detested Racine for writing ‘steed’ not horse), the avoidance of cliché, and above all, la chasse du bonheur. Has he been true to his younger self? ‘More or less’ (a phrase he liked to write in English). It is this realisation of continuity of character which allows him to fall in love with his own clumsy, priggish teenage self.

In my early twenties, I read Ernest Hemingway and wanted Grecian Doric columns on the moon. Now I read Elizabeth Bowen, and ache for corrugated iron. But am I the same person? More or less.

In those final pages he rides into the gates of Milan to dine on veal escalopes on the first floor of Casa d’Adda, and, for the first time understands that architecture can swell the heart. How to describe such happiness as I experienced in Milan, he asks? It is like looking at the sun.

I will finish the book tomorrow, he writes. But he never did. He had learned what he needed to know of himself, and he entrusted the manuscript to a bookseller in Milan with the instruction that it be published sixty years after his death.

Stendhal invented the word ‘egotism’ but detested a contemporary autobiographer who inscribed himself on history with ‘terrible quantity of Is and Mes!’. That is a challenge for modern times, too. My letter to The Guardian offering a ‘Stendhal service’ — that is, a writing class to reduce the use of the first person singular — never received a reply.

by Jean Stewart and B.C.J.G. Knight was first published by Merlin Press in 1958.Download

Brulard’, is also available to read here.Download

Notes

There’s no answer as to why Stendhal had to draw as well as write. The little plans, scattered throughout, seem to work for him sometimes as a prompt, and sometimes as proof, of his memories.

– Martin Bressani