Time’s Witness. History in the Age of Romanticism (2021) – Review

Anxious Objects

At some point in the annals of Western scholarship it was judged that the past could be restituted not only from textual sources but also from objects, that the material of history was equally important as its written archive. This major shift in historical approach was largely brought about by antiquarians, a fluid class of connoisseurs and collectors often drawn from an intellectual elite, some amateurs, some genuine scholars, all of whom shared a common interest in what they called ‘antiquities’. The latter consisted primarily of medals, coins, and inscriptions, but their collecting being compulsive, it quickly absorbed a dizzying array of objects: drawings, sculptures, pieces of buildings, vases, utensils, shreds of clothing, tools, weapons, games, and any other fragment falling from the past like a stone from the moon. In the eyes of the antiquarian collector, these odd morsels scornfully left behind by the more respectable class of historian acquired the status of relics. Their interest in them was not gauged in relation to their artistic merit, but to their historical value – they were ‘curiosities’ that provided the linchpin for a set of historical speculations.

Antiquarians were thus amongst the first scholars to gain an interest in a much wider set of artefacts, one situated outside the canon of good taste. Thanks to an empathic relationship with these broken fragments, they sought to get in touch with the past to make it whole again, thereby launching a resurrective process. Imaginatively transported into olden times thanks to the associative power of objects, antiquarians dwelled on that frontier between the objective and the imaginative.

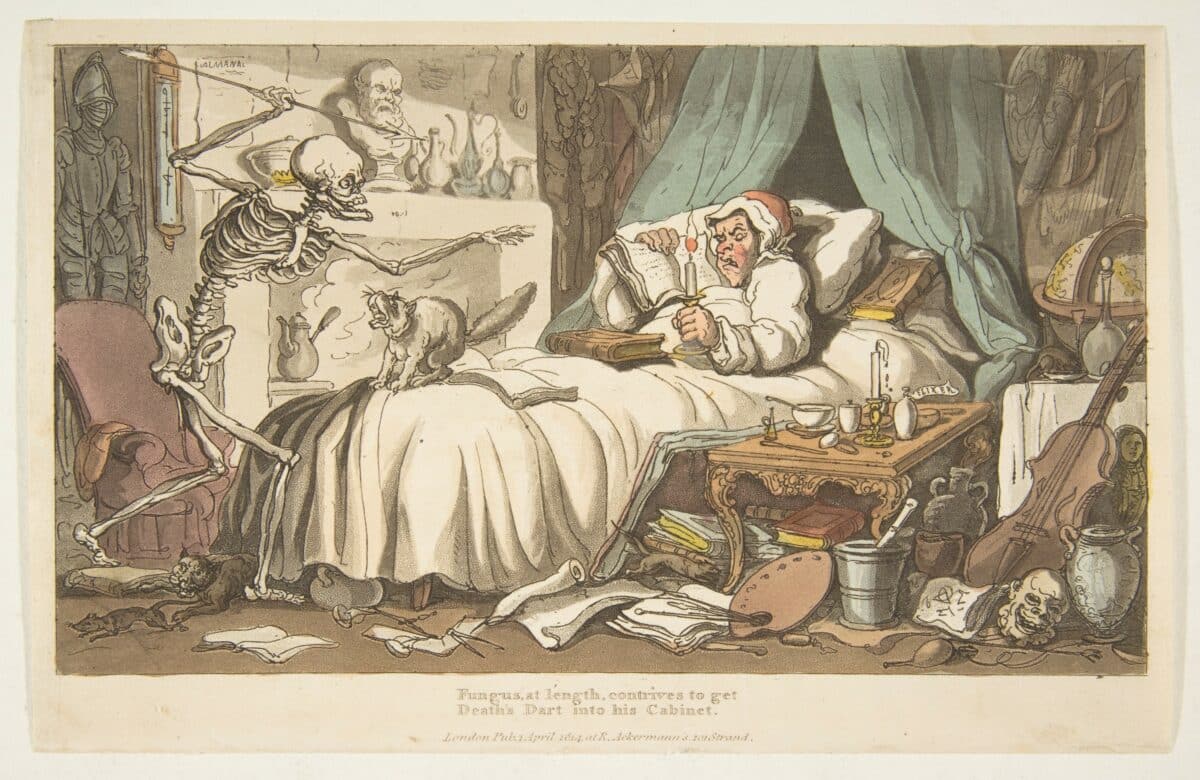

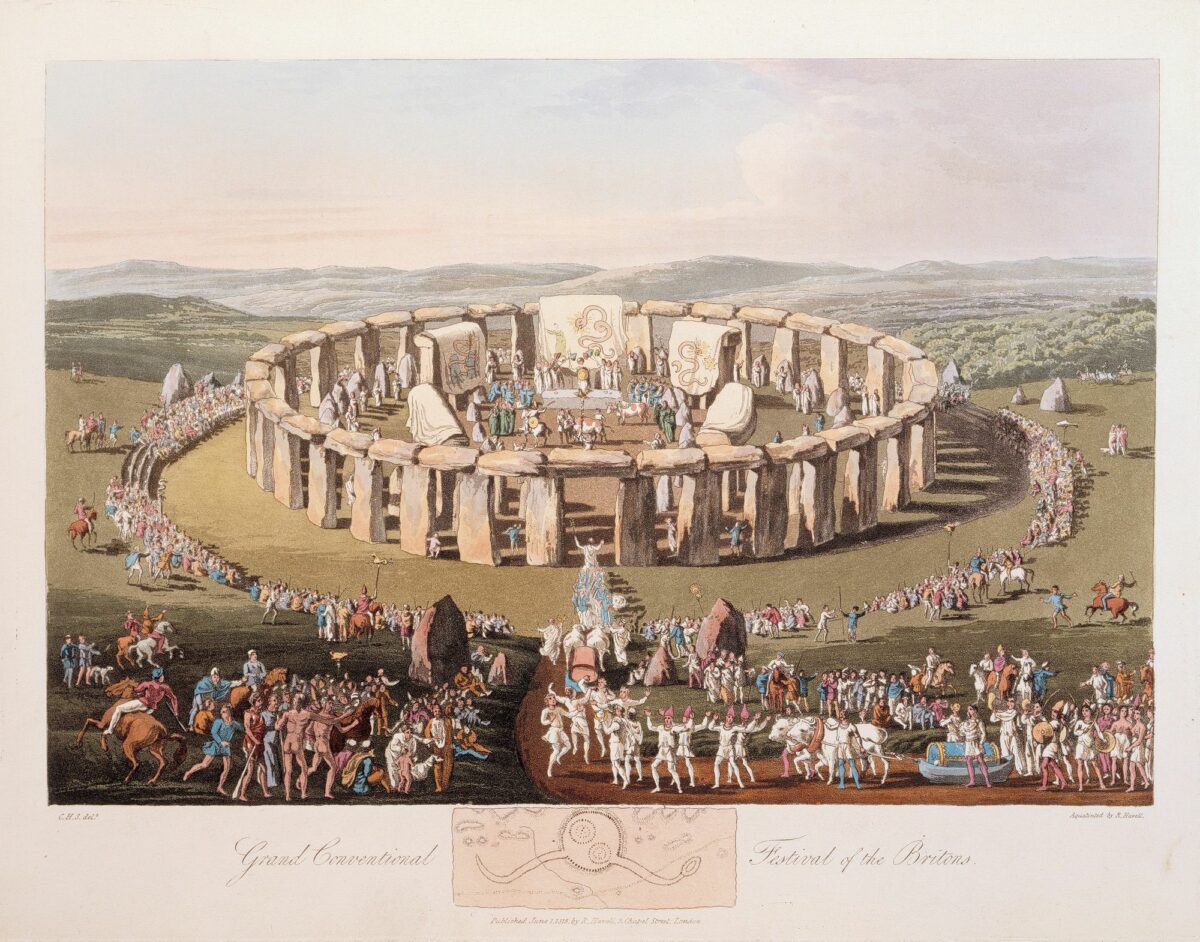

Rosemary Hill’s Time’s Witness: History in the Age of Romanticism explores the activities and life of British (and some French) antiquarians at that time when this class of historical workers reached their golden age, namely the period of Romanticism stretching from the late-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. Antiquarians of earlier generations had often been the butt of popular satires, described as dusty and boring grinds blinded by a pathological veneration for the past and prone to credulous flights of historical fancy. The mockeries weren’t always off the mark. The most famous of early eighteenth-century antiquarians, William Stukeley, believed that Stonehenge was the first church of a patriarchal Christianity whose cult was brought to England by an Oriental colony of Phoenicians led by the Tyrian Hercules, son-in-law of Abraham. Later in the century, Edward King, for a brief period President of the very respectable London Society of Antiquaries, claimed that St John the Baptist was an angel descended from heaven, and that heaven itself was located within the sun. These ludicrous examples may give an unfair picture of the often very rigorous scholarship carried by antiquarians, including Stukeley and King themselves. But such absurd flights of fancy are nonetheless revealing of the structure of desire that animated antiquarians: to reveal, through intimate manners and customs, the history of the nation as an enchanting, mythic process in touch with some deep (often divine) origin. It explains why at the dawn of Romanticism, antiquarian scholarship could move from the margin to the centre of culture. As Hill writes, the Romantics no longer looked to history for ethical and universal models but for the truth of individual experience, for the particularities of culture, and, above all, for the mythic ferment that made nations.

The Romantic quest was not devoid of irony: the yearning to penetrate how people once lived was kindled by a shattering of belief, by a modern sense of the ‘lack of reality’ of reality and an anxious urge for inventing new ones. The Romantic’s delectation in the past largely consisted in the pleasure of projecting oneself into alternative realities, which, as in drug-induced hallucinations, appeared infinitely more substantial and truer than the contemporary world. Their ‘antiquities’ were transitional objects, at the mid-point between the subjective and the objective, between an interior and an exterior reality, yet belonging to neither. Hill well understands Romanticism’s ironic disposition, which, as per her formulation, ‘made it possible to take seriously what one did not take literally’. But she decided to downplay the ironic and darker side in order to emphasise the lighter and more comforting aspects of dwelling in the past. In her rendition, Romanticism is above all the merging of facts with feelings and scrupulous scholarship with fiction.

Walter Scott is Hill’s most representative Romantic antiquarian, the true hero of her story, as he should rightly be. We now think of Scott chiefly as a poet and novelist, but he started his career collecting old ballads and antiquities and writing about them. It is his manic attention to ancient languages, customs, and manners that, ostensibly, led him to drift naturally towards the writing of historical novels and the building of the Castle of Abbotsford performing, as Stephen Bann once described, a careful balancing act between irony and naiveté. Hill describes with great relish how Scott would even seek to turn myth into reality, such as in his recreation of the Scottish regalia ‘venerable national reliques’, more or less invented de toute pièce.

Scott is only one of the many characters animating the pages of Time’s Witness, a book which is itself a sort of antiquarian collection, not of artefacts but of anecdotes drawn from the activities of the dozen or so antiquarians that Hill brings back to life for us. She has a knack for finding revealing picturesque stories and humorous quotes, reflecting a good knowledge of her primary sources. Time’s Witness is thus an easy read, not quite as absorbing and novelistic as Hill’s prize-winning biography of A.W.N. Pugin, but it is a cleverly woven fabric of multiple strands of themes, people and events. It is not aimed principally at academics, but rather at an educated British public. Neither primarily conceptual nor analytical, Time’s Witness sketches a portrait. Its theoretical underpinning is a sound and elegant essay written in 1969 on history in the Romantic age by British historian and life peer Hugh Trevor-Roper. Very little of the more recent historiography contaminates Hill’s traditional approach to her subject. Reading Time’s Witness is thus pleasant and soothing. The past as conveyed by Hill is a reassuring and stable space, which we absorb with a dose of nostalgia but a comforting sense of continuity.

Rosemary Hill’s Time’s Witness. History in the Age of Romanticism (2021) is published by Allen Lane. Copies of the publication can be purchased here.

Martin Bressani is William McDonald Professor at the Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture, McGill University.