Keep Digging and You Will Find What You Are Looking For: Alvar Aalto in Germany

In 1957, Alvar Aalto gave a speech in Munich entitled ‘Schöner Wohnen’.[1] He referred to his own design, the Hansaviertel apartment block in Berlin—his first project in Germany—as he described the key concerns in the design of the modern dwelling. (The construction of Aalto’s second German project, the Neue Vahr apartment block in Bremen, would commence some months later.)

In the speech, Aalto made reference to the city in which he spoke. He argued that beautiful living begins with the beautiful city, and that respect for history is a constituent element thereof. In Munich, he noted, the urban fabric laid out by the Romans continued to shape the development of the city centuries later. The ancient urban imprint of the city-centre was not just a faint residue of history, but an ever-living, dynamic rhizome that guided, or at least should guide, the work of the contemporary designer. The roots of foundational urban gestures deserved to be respected; continuity seemed both a more natural and more fruitful premise for a new project than confrontation. Aalto’s remark providentially pointed to his own approach to the major German cultural projects that followed the two residential schemes in Berlin and Bremen.

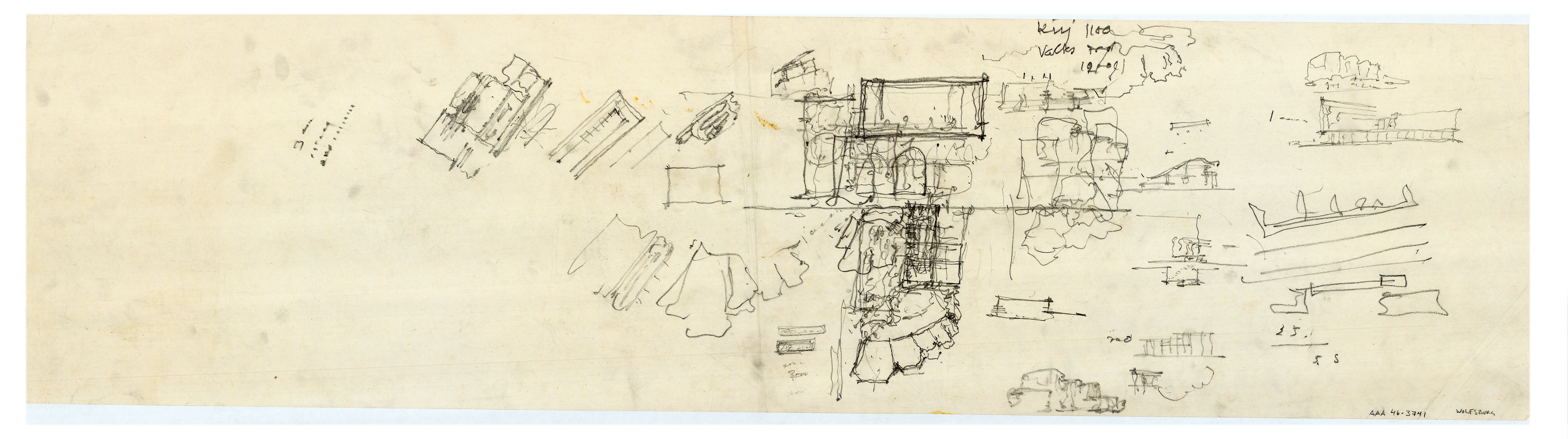

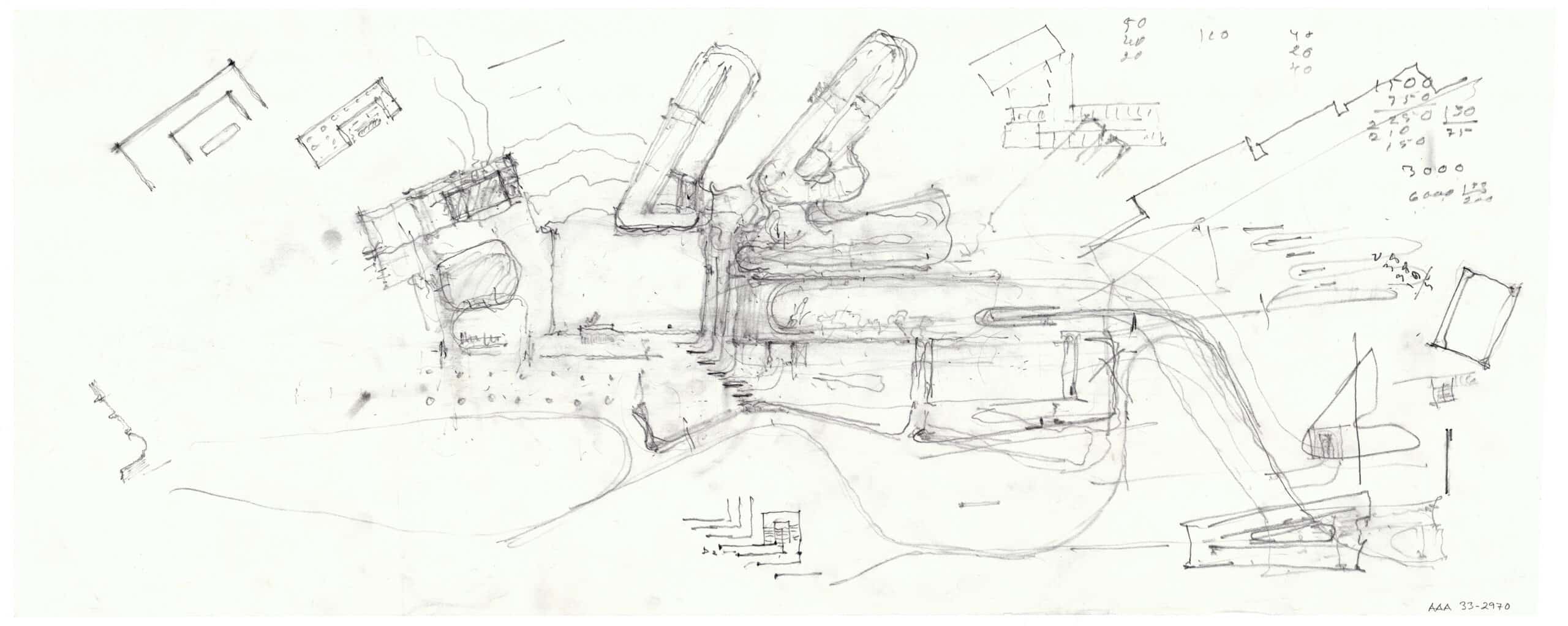

Urban and civic commissions were exercises in unearthing and selectively perpetuating physical traces of history, and the tool of choice for this unearthing was the pencil. Drawing was the primary means of excavation. Like farmers tilling soil, Aalto office members would remove the layers of a site, turn them over, dig in deeper, turn the matter over once more, shuffle it, dig in again, break it up and mix it, and ultimately let it settle. The ordered chaos of tilling—dig, stir, flop, overturn—is instantly legible in the drawings.

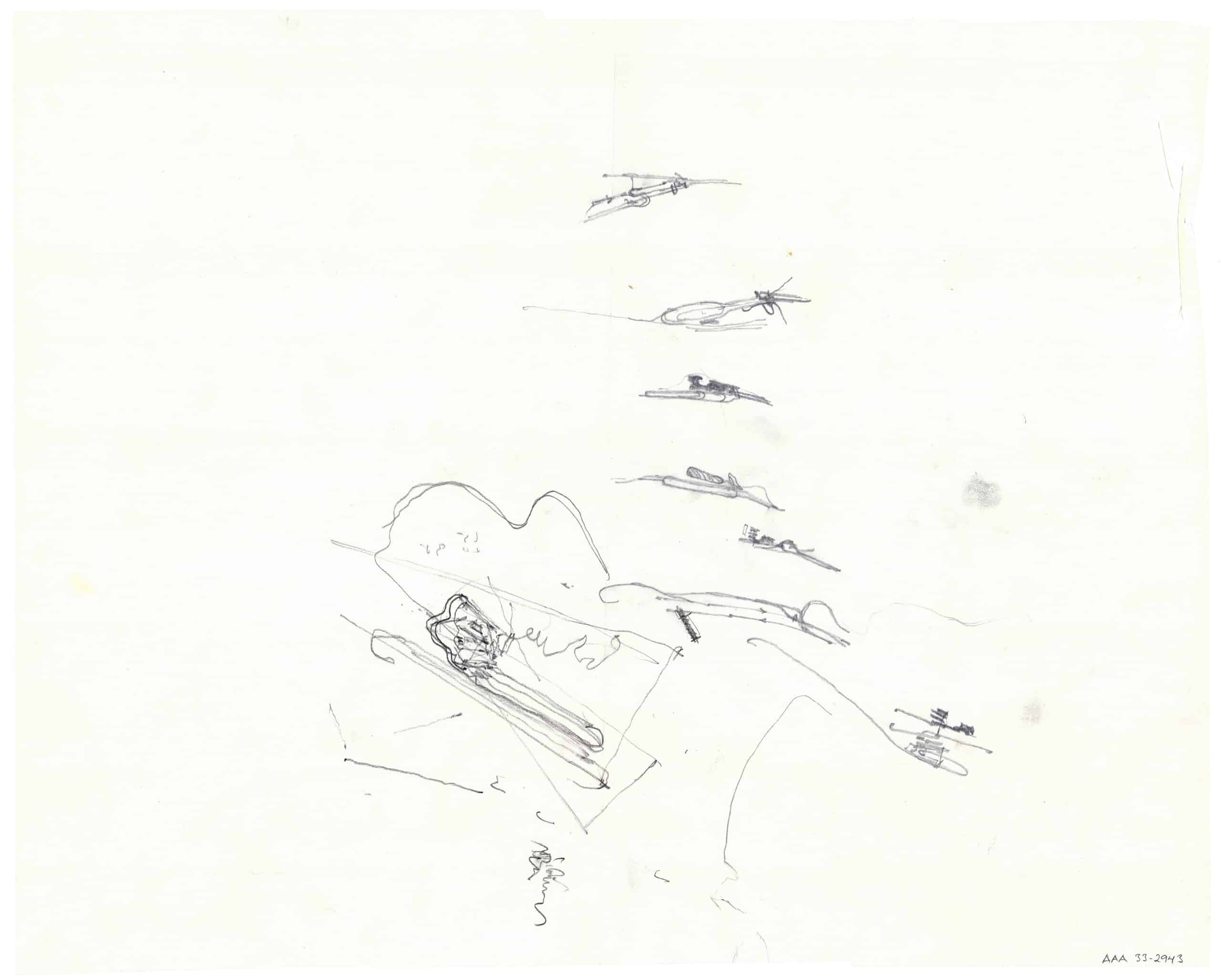

Each new project began with employees lifting onto the table—the paper—unidentifiable lumps of lines, reminiscent of drawn balls of yarn. Initial intuitive forms for a project were sketched as small knots, represented sequentially in slightly varied configurations. Just as knitters often need to untangle devilishly knotty buns of yarn before casting their first loops, shaking the yarn gently and inquisitively tugging at individual strands to unknot the snarled messes, Aalto studio members endeavoured to extract clean lines from their initial bundles of sketches. Through iterative sketching, the knots were carefully unwound and unfolded, resulting in increasingly confident lines shooting out from the original kernels, and ultimately bending into tentative suggestions of form.

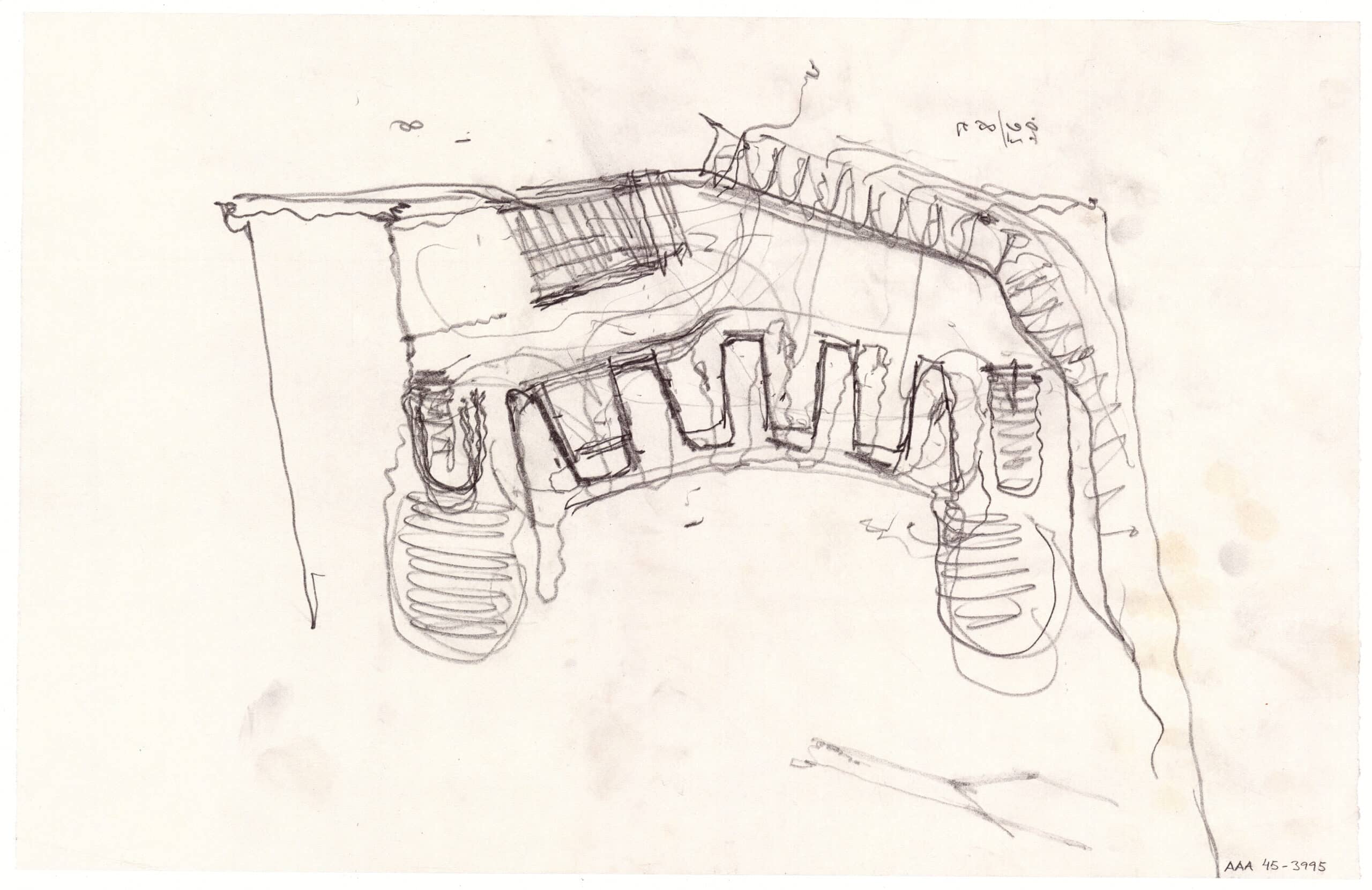

The strands then unfurl into markers of place and space: topographic lines, walkways, walls, enclosures. Sites appear on the paper either as soft bowls of land into which a project nestles, or modestly bulging mounds on top of which a project is placed on display. Aalto is often revered as a topographical architect, slave to his admiration for the landscapes of classical antiquity. Just as in any other project of his elsewhere, amphitheatres make cameo appearances in virtually every sequence of the site sketches produced for the German projects, sometimes as bombastic interventions polemically sculpted into an otherwise less remarkable plot, sometimes as fragile, almost ruinous forms that appear to grow naturally from slight irregularities in the ground plane. Natural and civic topographies interweave into one another.

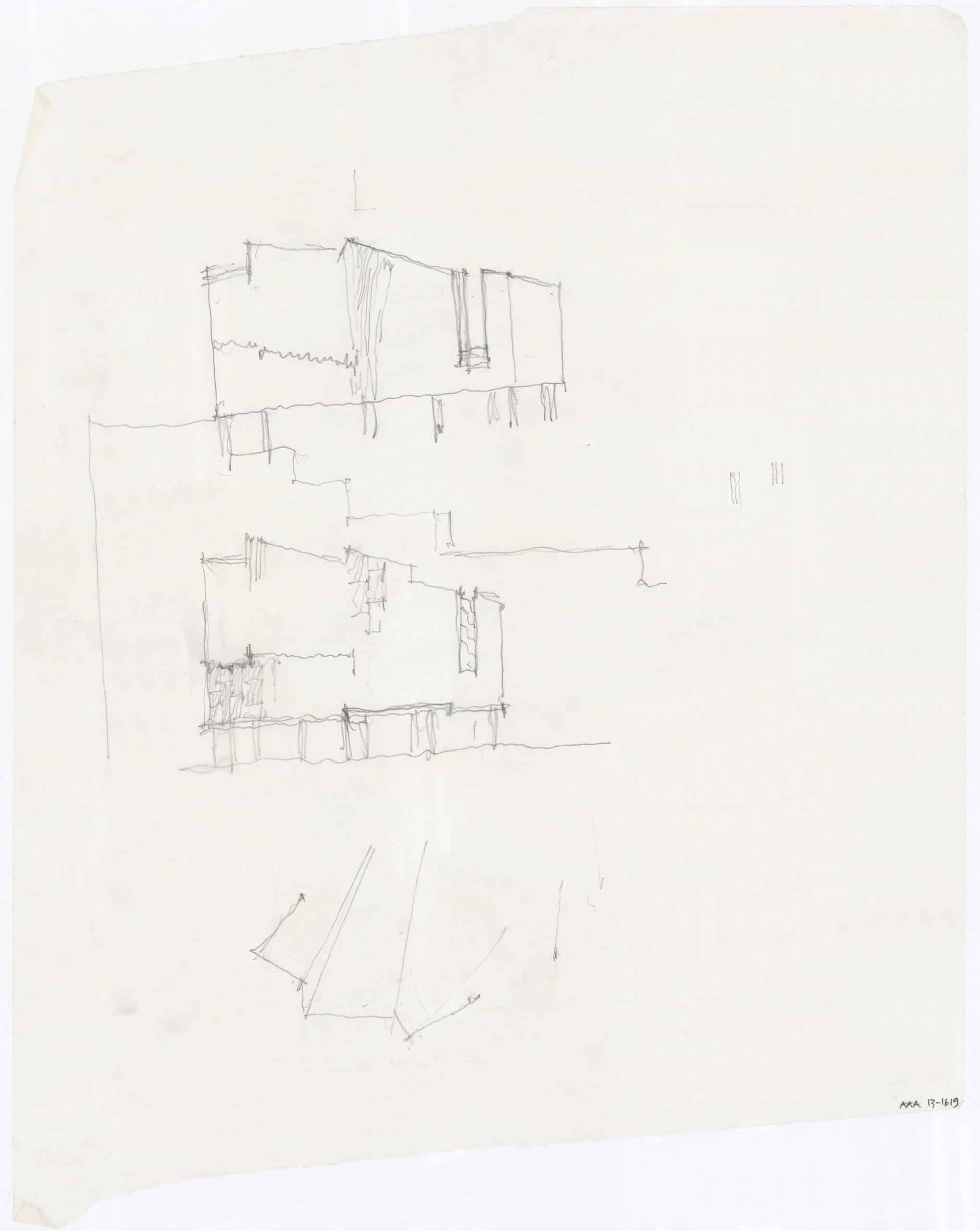

Gradational profiles are not limited to the amphitheatre type, but appear in various configurations and scales in plans, sections and elevations alike. Jagged inclines, edges and offsets serve as the persistent organisational gestures that soften down masses which would otherwise risk feeling too monolithic. Like fingers stretching out from a palm, blocks of mass are joined together but splayed apart into fanned plans. These drawings chronicle efforts to establish, manipulate and manoeuvre the ground condition, physically and metaphorically. Plans and sections appear as conjoined manifestations. They test one another, the horizontal plane serving as an alibi for gestures designed in the vertical, and vice versa. Sometimes they summon perspective to offer a third opinion: quick croquis of key perspectival moments such as entrances often complement the ever-present pairs of plan-and-section.

© Alvar Aalto Foundation.

The result of breaking down building masses in plan is a family of jagged perimeters that come to define asymmetrical public space. Decidedly different from their purely geometrical counterparts, these irregular piazze mesh together a variety of experiences, ranging from the ceremonial gravitas of wide steps to the guarded intimacy of smaller urban alleys and niches. Topography becomes not just scenography but choreography. These interstitial spaces speak to the Aaltos’ sustained interest in the social dimensions of urban space, a ‘middle-ground’ suspended between the ostensibly more typical modernist poles of interest, the scale of the domestic unit on the one end and that of master planning on the other.[2]

There is something vaguely mediaeval in the resultant urban ground plans. It is hardly a stretch to imagine Aalto absorbing some of the mediaevalising tendencies of his German peers into his own approach, especially given that he consistently professed to admire the Middle Ages as a paragon of the virtues of collective labour (the joyous union of carpenters and stonemasons), craft (the haptic richness of masonry and timber), and richly textured urban fabrics (higgledy-piggledy houses abutting a cathedral and its grounds).[3]

The mediaevalist reverberations in West German architectural culture in the late 1940s and 1950s framed designers’ engagement with pressing questions of identity, reputation and character. How was the country to present itself to the international community after the Second World War? What kind of past(s) could and should building art refer to?

Aalto’s reputation as an architect from the far North of Europe, and especially as a so-called softener of modern architecture, was appealing in the socio-cultural milieu of the immediate post-war years. Summoned from Finland to ‘give character’ to cities such as Wolfsburg and Darmstadt, the driving questions Aalto office members were asked to address in their civic and cultural commissions in Germany were ‘What is a city, and how does it portray itself to the world?’ Drawing served as the medium in which to begin formulating answers.

Notes

- Cf. Aalto, ‘Schöner Wohnen’, in Alvar Aalto in His Own Words, ed. Göran Schildt, trans. Timothy Binham (New York: Rizzoli, 1997), 260–61 (260).

- Cf. Harry Charrington, ‘The Makings of a Surrounding World: The Public Spaces of the Aalto Atelier’ (PhD diss., London School of Economics, 2008), 140.

- Cf. Alvar Aalto, ‘What is Culture?’ in Alvar Aalto in His Own Words, ed. Göran Schildt, trans. Timothy Binham (New York: Rizzoli, 1997), 15–17.

Dr Sofia Singler is an Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of Cambridge, and a Fellow and College Lecturer in Architecture at St John’s College, Cambridge. Her monograph The Religious Architecture of Alvar, Aino and Elissa Aalto is published by Lund Humphries in October 2023.

Sofia Singler, ‘Keep digging and you will find what you are looking for: Alvar Aalto in Germany,’ in Alvar Aalto in Deutschland: Gezeichnete Moderne/Alvar Aalto in Germany: Drawing Modernism, ed. Sofia Singler (Berlin: Tchoban Foundation Museum für Architekturzeichnung, 2023), pp. 14–41.

Alvar Aalto in Deutschland: Gezeichnete Moderne/Alvar Aalto in Germany: Drawing Modernism is on show at the Tchoban Foundation Museum for Architectural Drawing until 14 January 2024.