OMA: Rem Koolhaas—Initiative

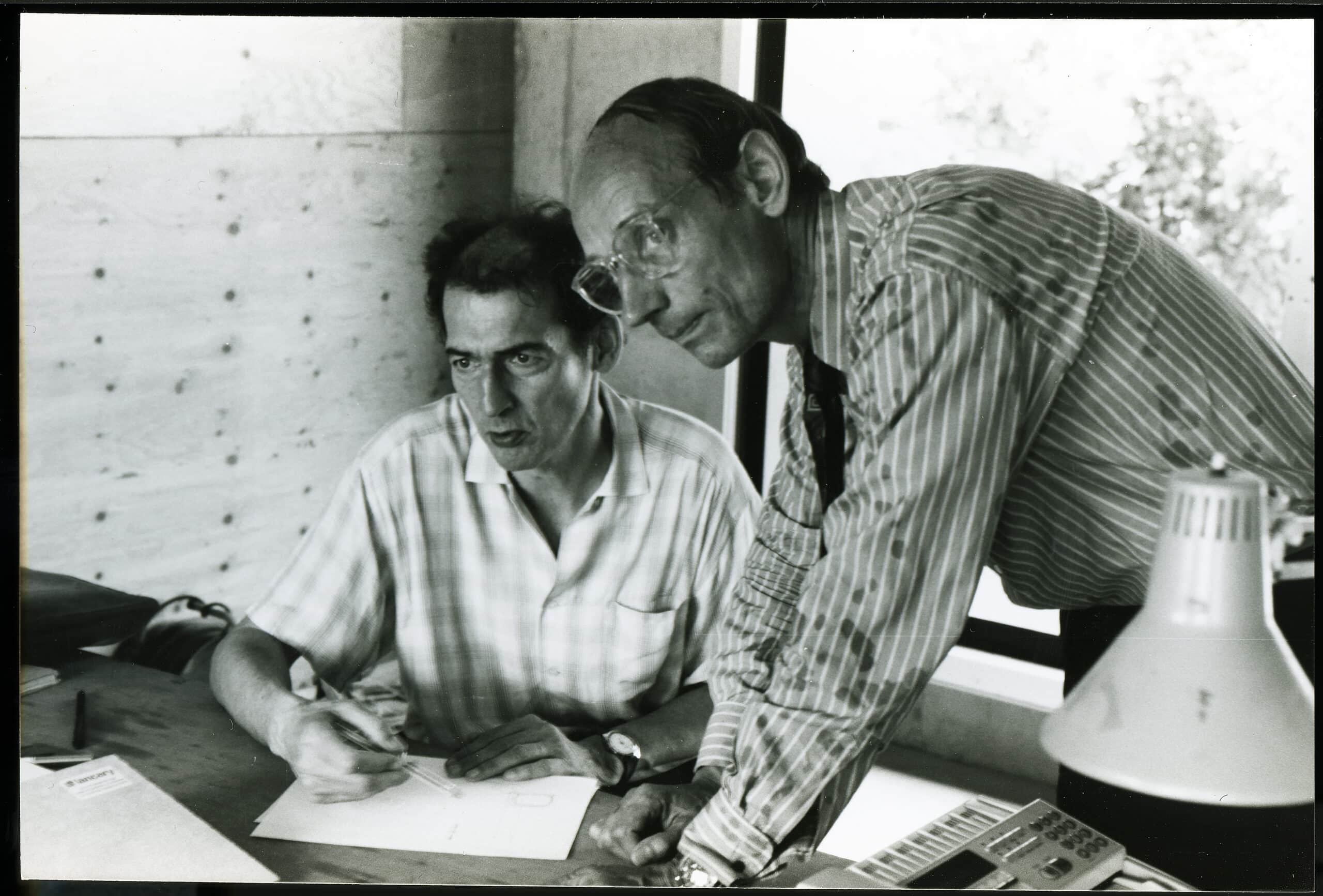

This is the sixth and final post, in the series titled OMA CONVERSATIONS. The series is the result of a collaboration between Drawing Matter and architect Richard Hall who, over the past two years, has conducted twenty-three in-depth conversations with key collaborators working with OMA during its formative years. Drawing Matter has long had an interest in the work of OMA in this period, in particular the role of Rem Koolhaas in establishing the model of a horizontal organisational structure and the purpose, and techniques, of drawing in its distinctive repertoire.

REM KOOLHAAS—INITIATIVE is a conversation with Rem Koolhaas on the challanges of becoming an Office.

Find out more about the project, including a list of all posts, here.

Rem Koolhaas is arguably the world’s most influential living architect, consciously adopting the architect-as-public-intellectual model central to the Modern project (from the Renaissance until the second half of the Twentieth Century). For nearly fifty years he has organised and mobilised OMA as a vehicle for engaging with the constantly evolving conditions of modernity.

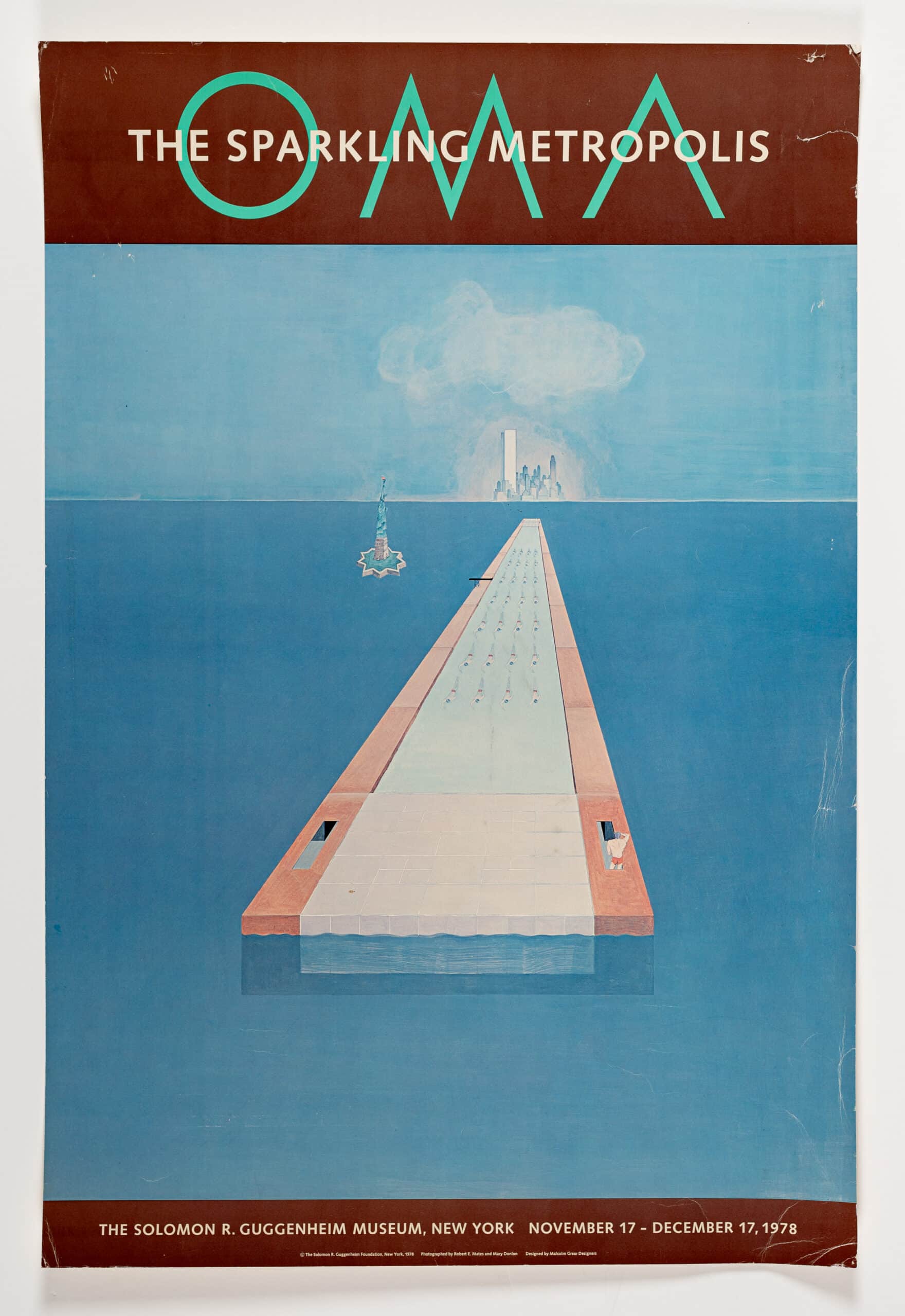

As early as Delirious New York (1978), Koolhaas articulated the value of collaboration—of collective intelligence—in architectural production. A significant aspect of his work as the head of OMA has been the orchestration of conditions and tactics that enable this activity to reach its maximum potential.

In this conversation, Koolhaas discusses the impetus for OMA and his attitude towards collaboration as a means for pursuing the project of OMA.

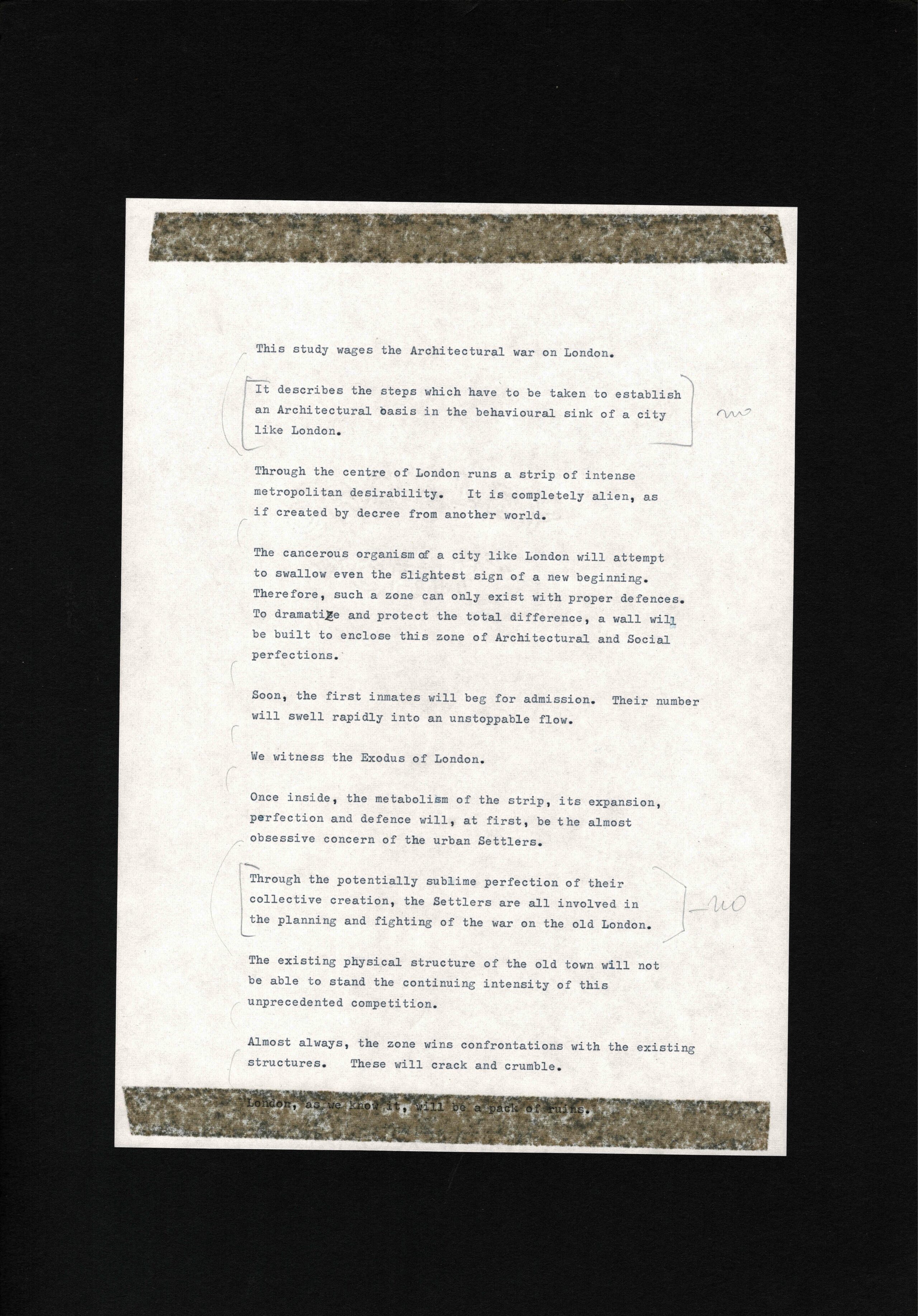

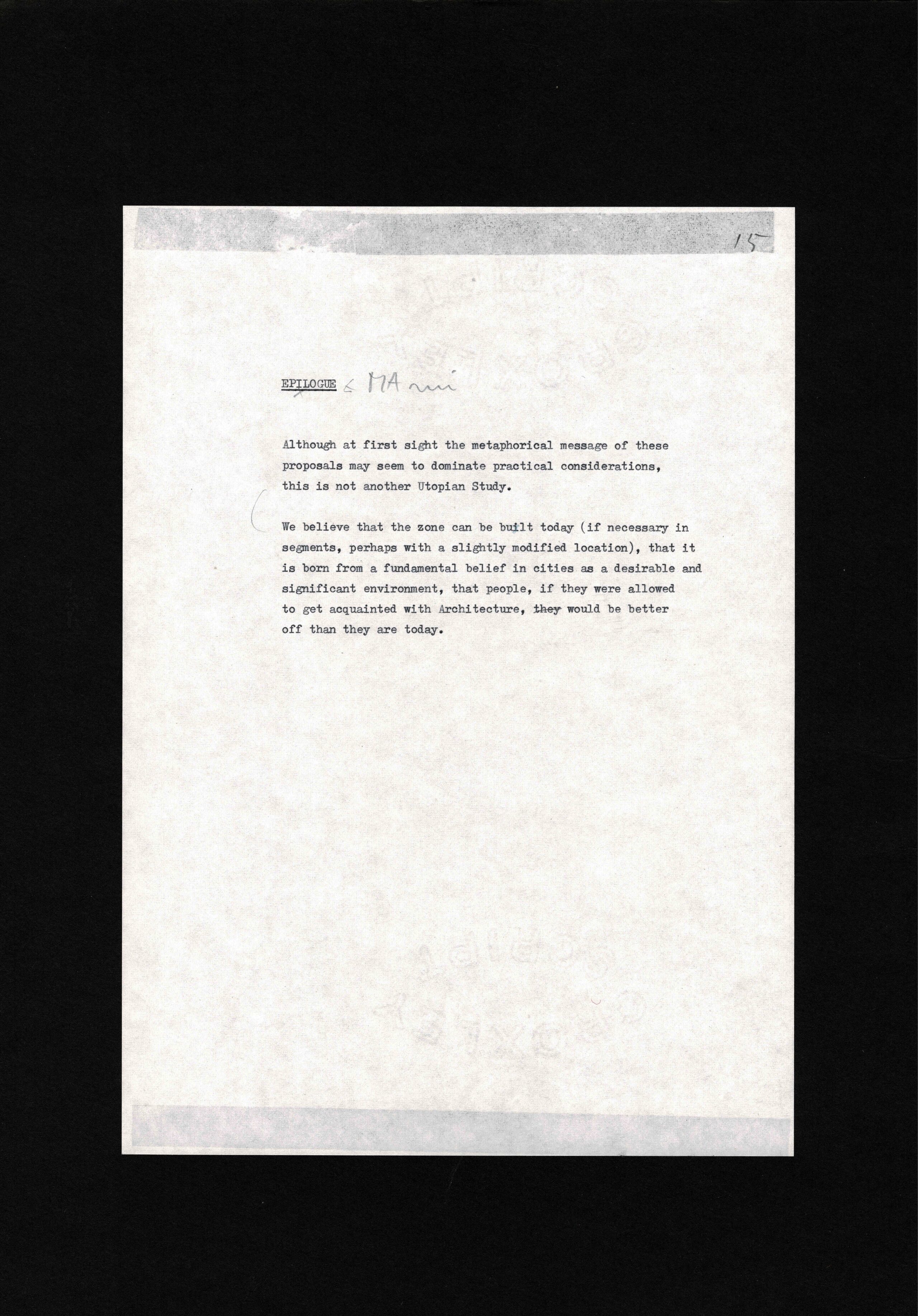

OMA, Exodus – The Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture, 1972. Black plastic portfolio containing typescript with hand amendments, slides, 437 x 310 x 30 mm. DMC 3151.1.5

‘It was also a very important part of being a journalist. As a journalist I didn’t simply write pieces: I also did layouts for the paper. There—even if it’s at a very low level—you orchestrate the composition of a very complex entity. Before that, my father ran a cultural institute, when we lived in Indonesia. Part of that institute had a section on music, and I was friends with the guy who ran it. He involved me in an early fetishism with the idea of the orchestra.

There’s a very English film, The Young Persons Guide to the Orchestra. It’s really very corny because you have the conductor, ‘Now the triangle…’, and he has given a space to every instrument—that really fascinated me. Probably even the role of the director. But also, Gamelan—do you know this very interesting Indonesian form of music? An extensive group, with the whole orchestra sitting on the ground. The music is produced in a very mysterious way—almost like wind blowing through a field—and then, suddenly, energy emerges from certain points, and then shifts.

I think basically all of these experiences made the idea of collaboration and orchestration a very attractive proposition. I’m even wondering if it had something to do with the inherent mood of collaboration in the period following World War II…where basically a whole generation needed to produce something. Maybe I was marinaded in this kind of collectivity.’

‘It’s interesting that you refer to Associated Architects. I’ve always been baffled by the fact that I described my own future, and no one seemed to pick-up on it. So superficial in a way.

But of course, you know, the question, ‘Why?’, implies intentionality! I think I can only partly explain the reason. I had studied it in New York and was impressed. This relates to why you want to study an office. In the beginning, when I conceived the office, the name OMA was important. It was not a personal label, but from the beginning something with the potential to be much bigger. So, it was an elastic identity that could shrink and expand.

The Associated Architects model requires more than one participant. I felt that if you acknowledged that, it would probably give more incentive to the participants. It’s basically an incentive to participate and to create—which is perhaps the most efficient way of encouraging involvement.’

‘In the early-80s, I think it was a shared discovery (working process). Once the process became clearer, it generated for me, on the one hand, a constant incentive to change it; and on the other hand, a greater experience with the process, which allowed it to operate on its own terms. Of course, by enabling so many participants in the process to have a voice, it also means all the participants had a particular definition of the process of OMA and would try to define it. Every time I would see a defined description—and this has really been a constant—I was horrified and would say, at least to myself, ‘You’re missing the point’, ‘It’s totally different’! This has somehow been a constant incentive for me to change.

At certain moments, the whole idea that everyone knows that you need many versions, that everyone knows there is an editor who is just saying, ‘Ok, let’s do this’ or ‘Let’s do that’, I contradicted many times by simply going for the jugular at the first moment! In that sense, I’ve never been a believer in the mythology of the OMA process.’

‘For me, a key question is in what context are you producing? Who’s facing you? Is it an individual? Is it a committee? Is it somebody with imagination? For instance, the leap from a private house (Y2K House) to Casa da Musica has nothing to do with alternatives. It was simply a flash of insight. On the other hand, the Seattle Public Library was a long, drawn out process with thousands of voices—both outside and inside—who had time to refine and modify the whole thing. So, it’s very uneven. There are many different factors in play at the same time.

In all of those interviews, I’m sometimes stunned by the repetition of some of those mythologies.’

OMA, Exodus – The Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture, 1972. Black plastic portfolio containing typescript with hand amendments, slides, 437 x 310 x 30 mm. DMC 3151.1.16.

‘I think that is incredibly complex to answer (value of early OMA). Obviously, in any career there’s a beginning and middle, then the beginning of the end, to the end. You have to apply a consistent ingenuity and ambition—but the ambition obviously changes in all these phases.

There’s a lot to be sentimental about in the early period; it was pure…blah, blah, blah. But it was—in its own way—an incredible success story of going from nothing to buildings like Congrexpo in seven years. In that sense, there is an almost unbelievable expansion. It’s impossible to imagine that same expansion could continue in the next ten years, or the next ten years, or the next ten years…because you would be on Mars!

So, it was incredibly exciting but, for me, so was the decade after. It was spectacular in terms of dedication, I would say. It was spectacular to be able to mobilise the support of so many people as co-authors.’

— Rem Koolhaas Transcript click here.