Bruno Taut’s ‘Alpine Architektur’

This text was first published in DMJournal No.1: The Geological Imagination (2023). Print copies of the Journal, and subscriptions for the first three issues, are now available through our online bookshop. We are currently accepting abstracts for the third issue of DMJournal. Find more information here.

In January 1917, the architect Bruno Taut avoided conscription by agreeing to work in the drawing office of a factory in Bergisch Gladbach. As a pacifist he despaired at the endless misery of World War I, writing to his brother Max—also an architect—in January 1918: ‘How loathsome politics now is! But I shan’t run away, my Glanzwelt [sparkling/radiant world] lives within me.’ [1]

Taut’s Glanzwelt existed not only in his head but in the folio of large-scale drawings on which he started working on All Saints’ Day 1917: Alpine Architektur. In spite of its title, this project was neither about the Alps nor architecture in any descriptive sense. Rather, it was a late flourishing of German Romanticism, with its creative engagement with nature and with the aesthetics of the sublime, according to which both terror and exultation were attached to the most awe-inspiring works of the cosmos: from mountains, glaciers, and roaring cataracts, to the stars and the planets. [2] Literary inspiration came from the novels of Paul Scheerbart, the passionate advocate of glass architecture, with whom Taut had collaborated on the celebrated Glashaus at the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne, a prismatic glass pavilion expressly derived—according to Taut—from the Gothic cathedral. Scheerbart also brought Buddhist philosophy to the mix, together with Gustav Fechner’s theory of universal animation, which saw all matter, organic and inorganic, as interwoven life forms linked in a cosmic chain that runs from the earth to the stars.

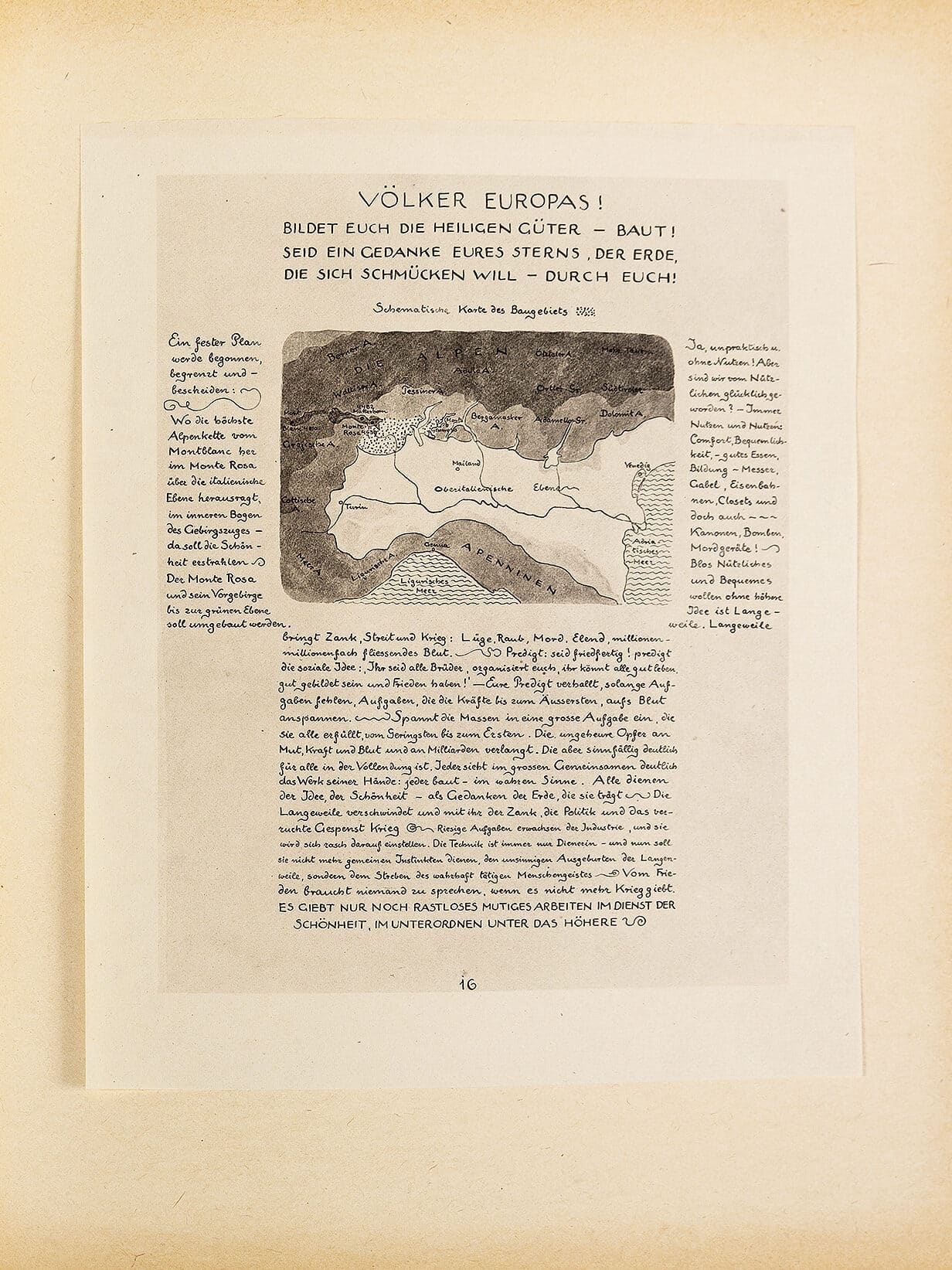

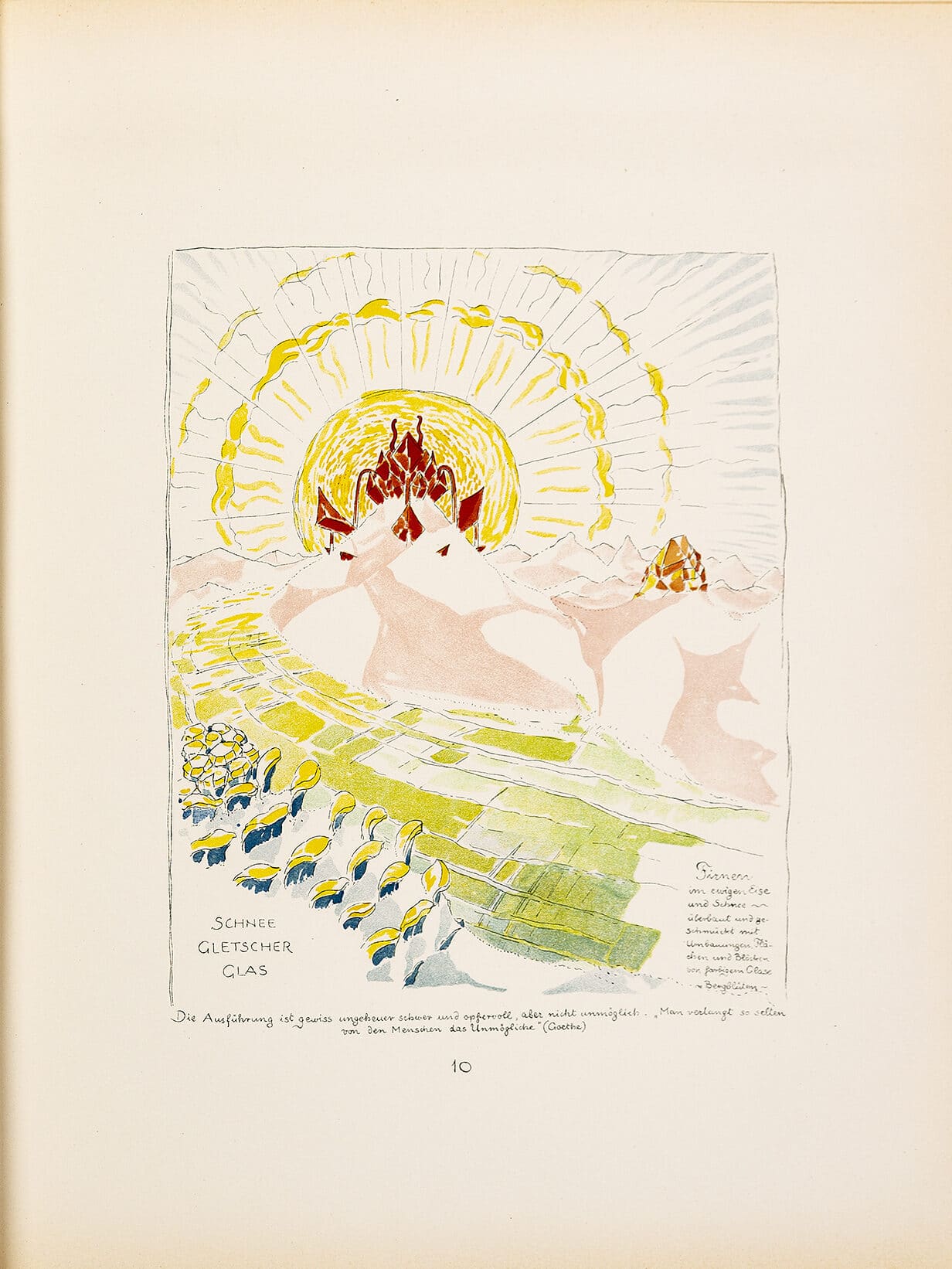

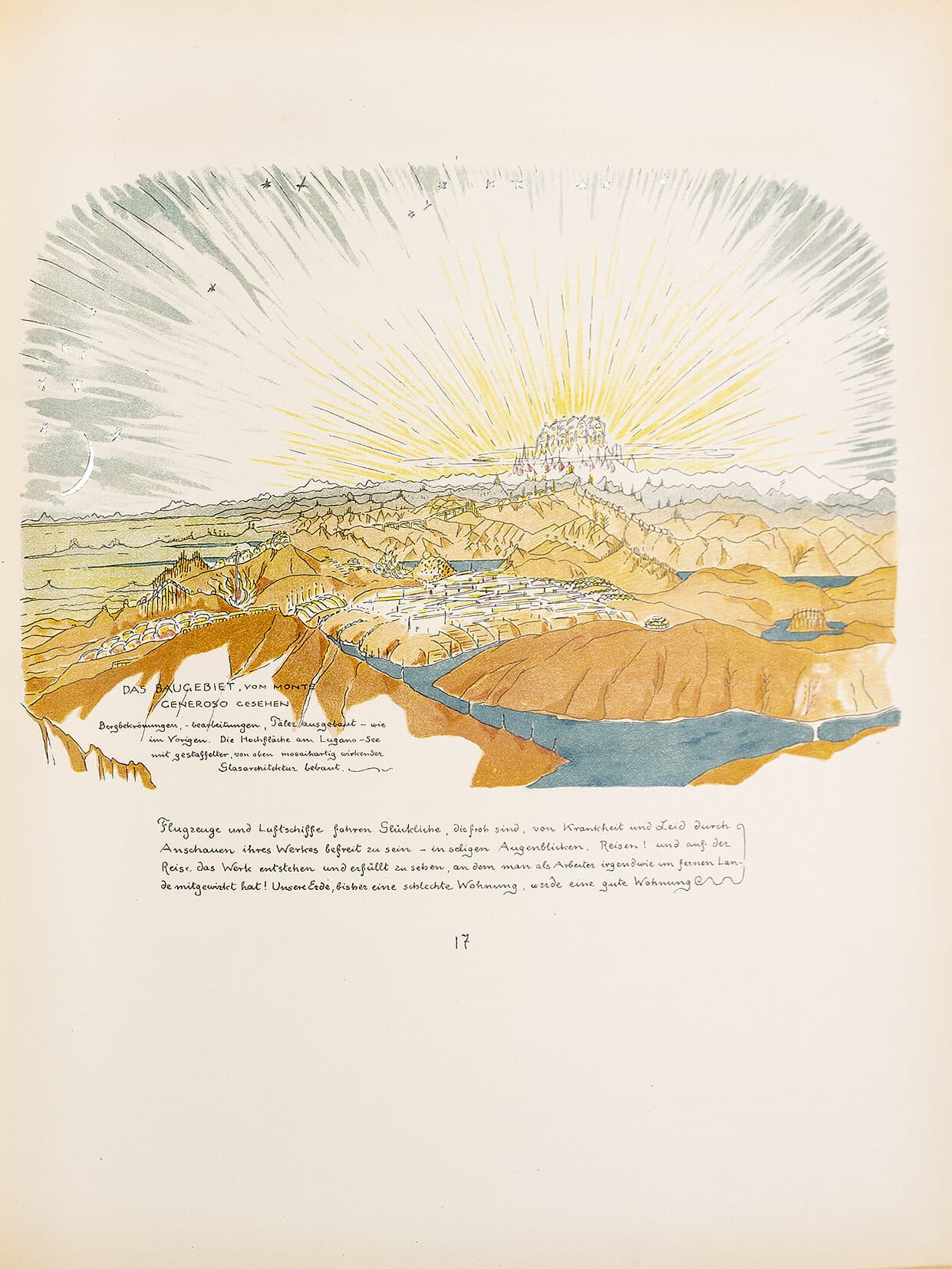

In thirty drawings with marginal texts, Taut invoked a brilliant new technology of steel, glass, and aviation that would elevate the human spirit high above the trenches of Flanders by building crystalline temples on Alpine peaks and launching glass satellites into space. Halfway through the folio (Fig.1) Taut urges the European nations to build for peace rather than war, arguing that the technology that supports the comforts of modern life also builds ‘canons, bombs, and murderous machines’. Utility should be abandoned, he insists, and the impractical and visionary pursued instead. The world was to be redeemed through art. Beside his drawing of radiant glass structures set in the eternal ice and snow of the Alps, Taut quotes Goethe’s regret that ‘One so rarely demands the impossible of mankind’ (Fig.2).

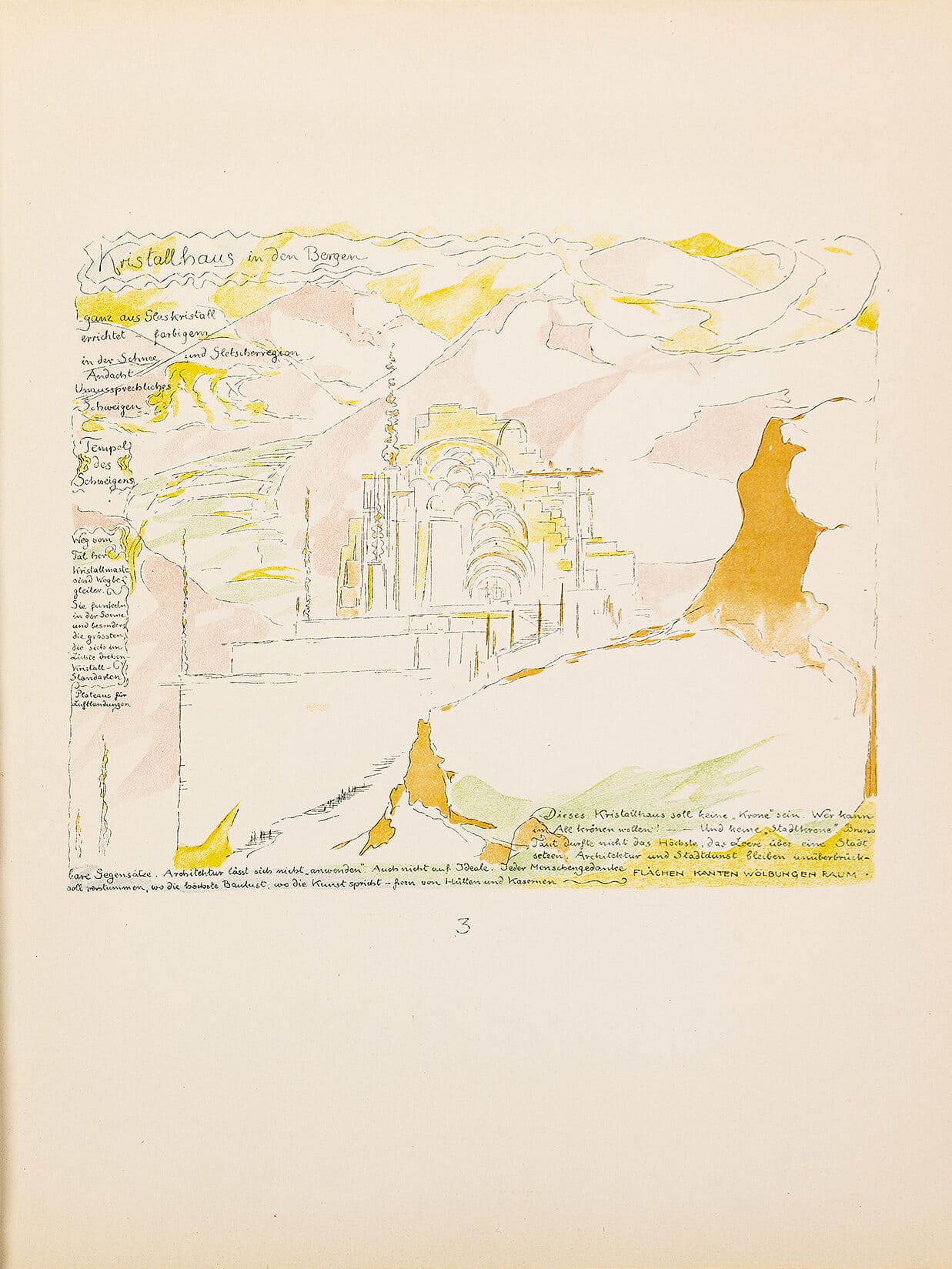

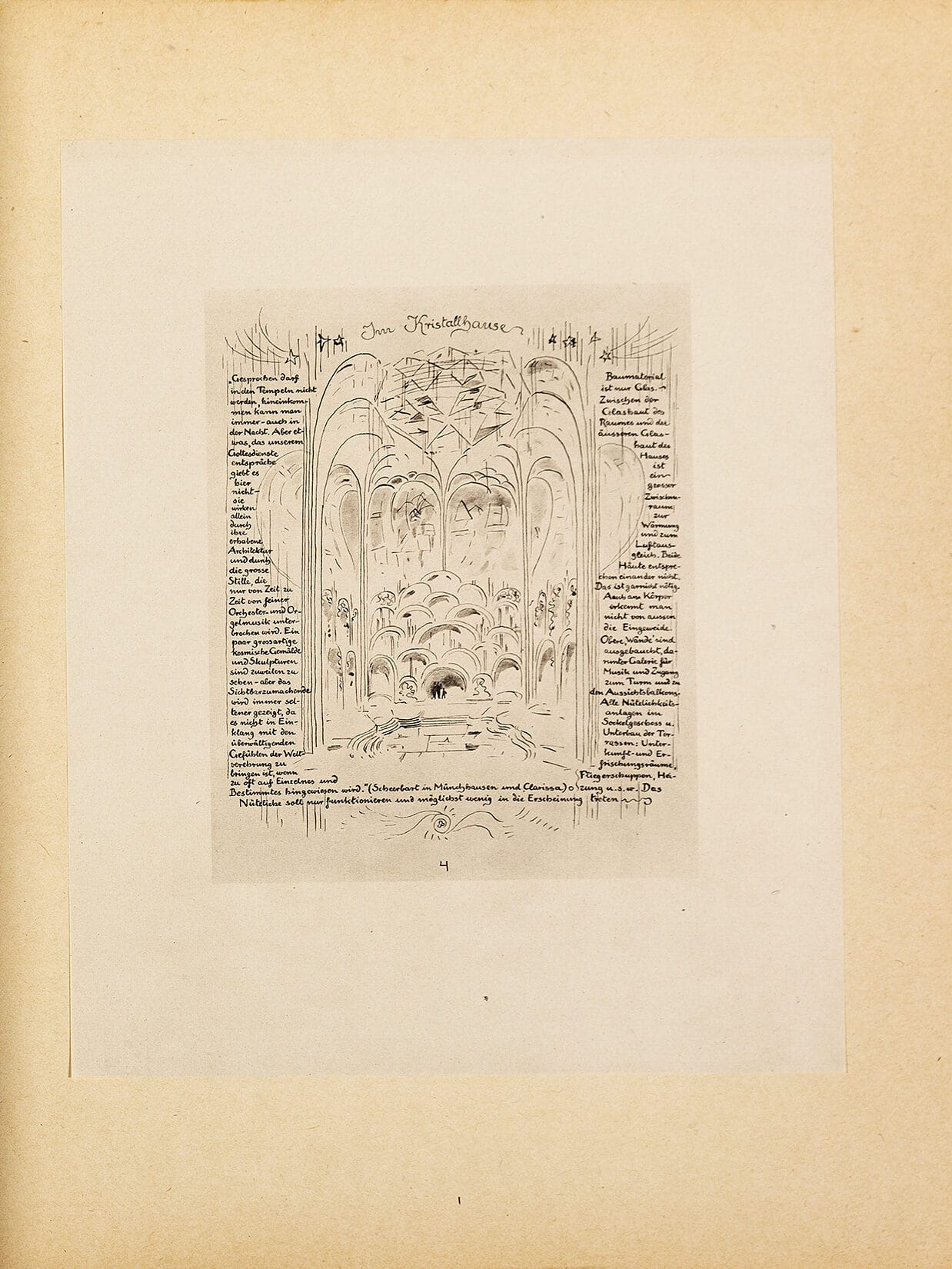

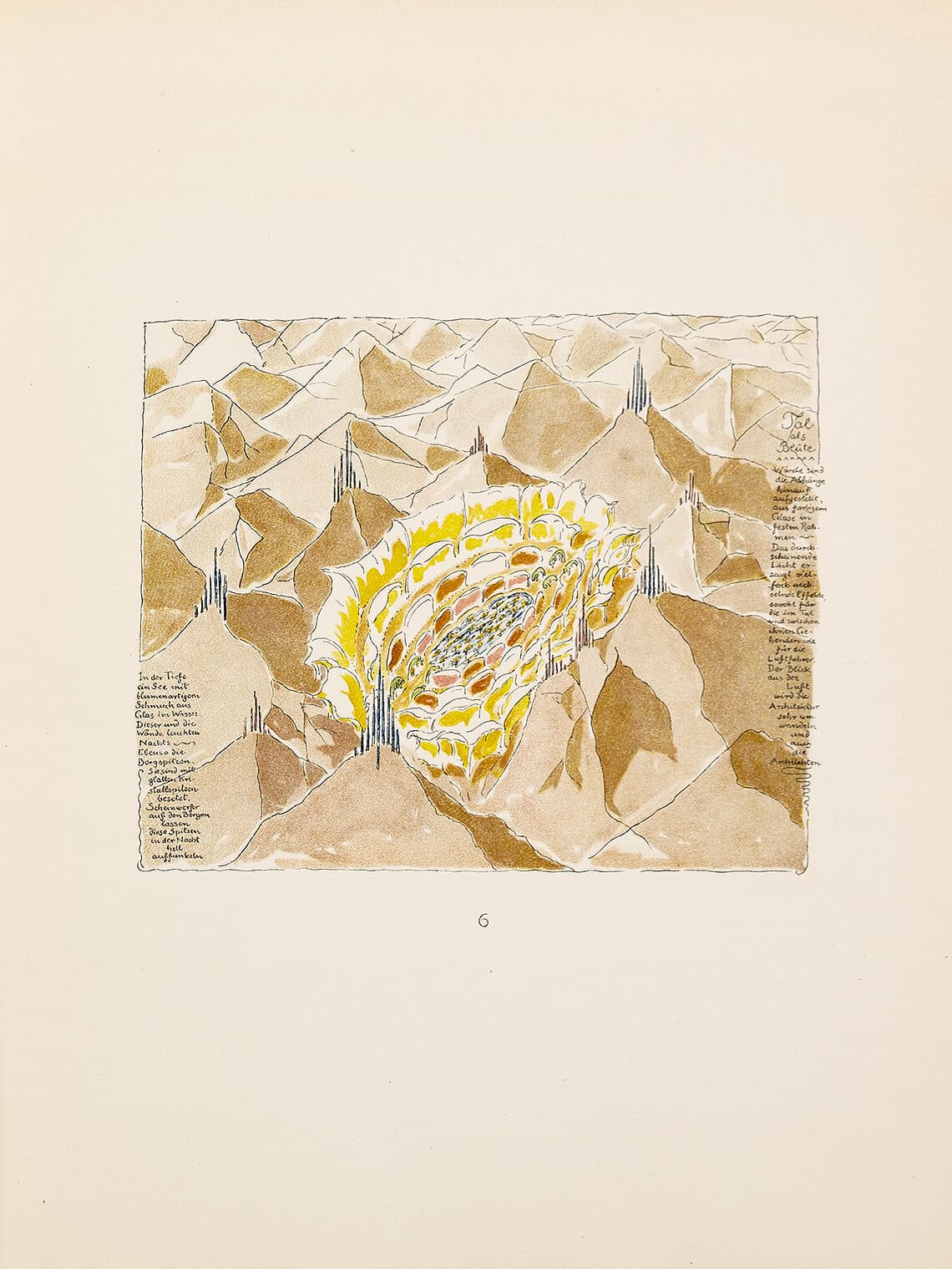

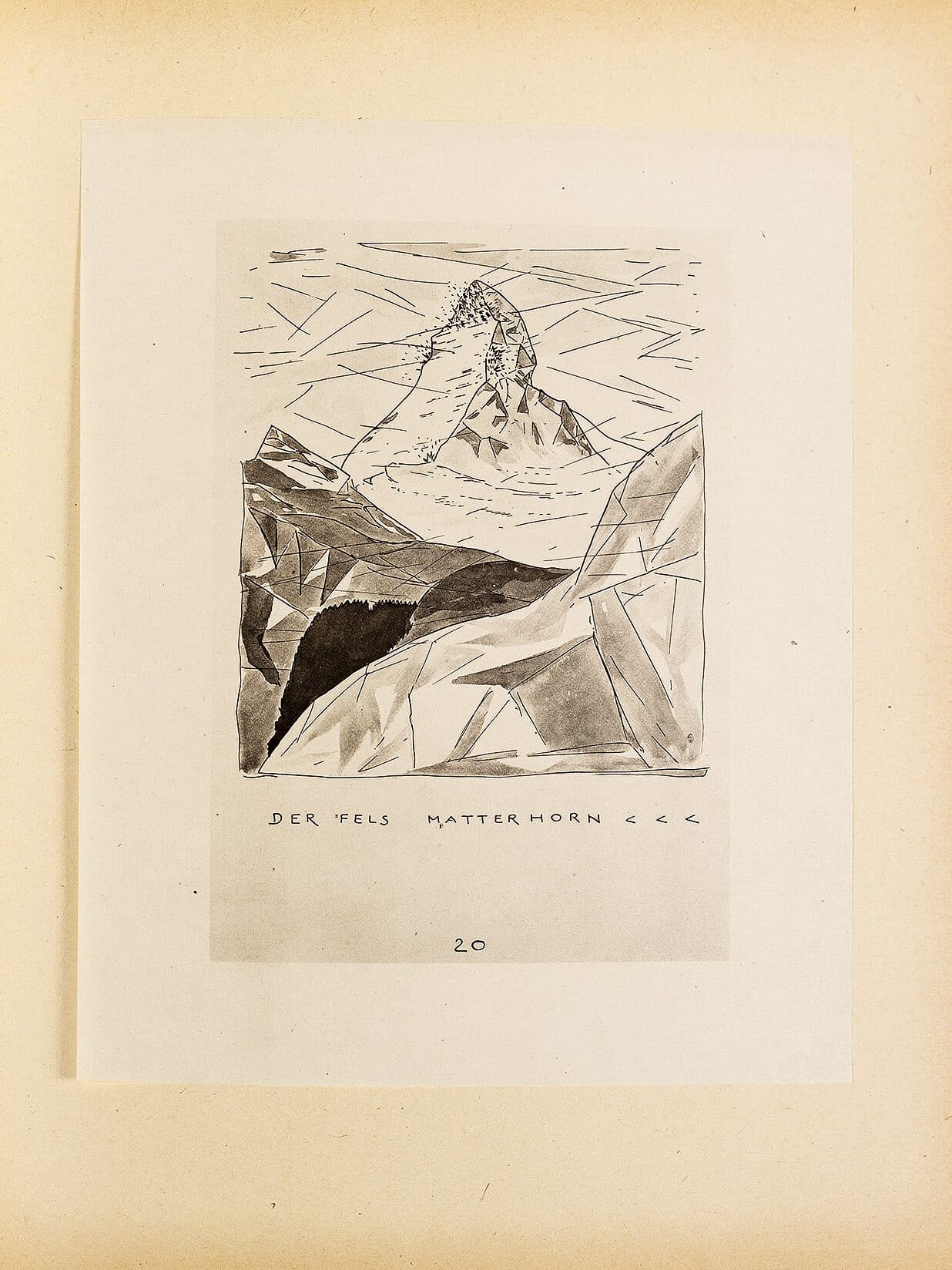

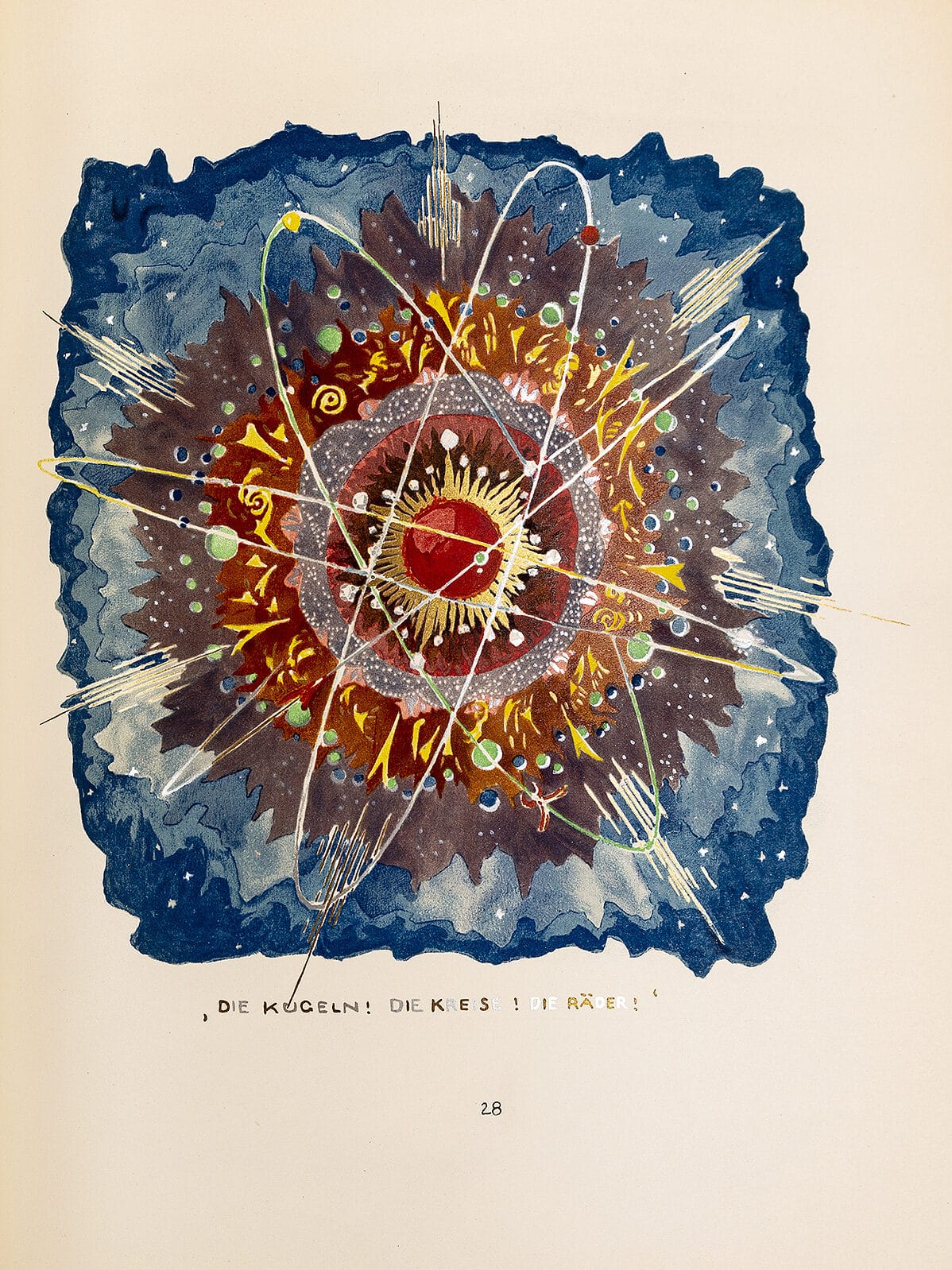

The crystalline buildings are described as cathedral-like spaces of contemplation, whose silence is broken only by dulcet music. No practical function is specified beyond aesthetic ennoblement: ‘They take effect solely through their sublime architecture’ (Figs 3, 4). The erotic charge of the project is made manifest in the image of an Alpine valley, opening like a glass flower in response the glass towers that surge upwards toward the heavens (Fig.5). From the general proposition, Taut moves to schemes designed for specific sites in the Alps such as the Monte Rosa Chain (Fig.6) and the Matterhorn (Fig.7), before heading off into an astral architectural fantasy (Fig.8). The folio approaches its conclusion with an image of the solar system, titled ‘The Spheres! The Circles! The Wheels!’ (Fig.9), a reference to Scheerbart’s 1910 essay ‘Das Perpetuum Mobile’, acknowledging ‘the omnipresent mechanics of the universe’. [3] The Gothic spires shooting out from the planets that have journeyed from medieval Europe to the stars foretell Lyonel Feininger’s drawing of a crystal cathedral, with which Walter Gropius launched the Weimar Bauhaus in April 1919.

Notes

- Bruno Taut, letter to Max Taut, 30 January 1918, quoted in Iain Boyd Whyte, Bruno Taut and the Architecture of Activism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 87.

- See Iain Boyd Whyte, ‘The Expressionist Sublime’, in Expressionist Utopias: Paradise, Metropolis, Architectural Fantasy, ed. Timothy O. Benson (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art / Washington University Press, 1993), 118–137. Reprinted under same title (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

- Matthias Schirren, Bruno Taut, Alpine Architektur: eine Utopie—A Utopia (Munich: Prestel, 2004), 104.

DMJournal–Architecture and Representation

No. 1: The Geological Imagination

ISSN 2753-5010 (Online)

ISBN 978-1-9161522-3-6

About the author

Iain Boyd Whyte is Professor Emeritus of Architectural History at the University of Edinburgh. He has published extensively on architectural modernism in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, and on post-1945 urbanism. A former Getty Scholar, he was co-curator of the Council of Europe exhibition Art and Power, shown in London, Barcelona and Berlin in 1996/97. He is founding editor of the journal, Art in Translation, has served as a Trustee of the National Galleries of Scotland, and in 2015–2016 was Samuel H. Kress Professor at CASVA, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. His recent publications include Beyond the Finite: The Sublime in Art and Science (2011) Metropolis Berlin 1880–1940 (2012); and Hot Art, Cold War, 2 volumes (2021), an anthology of texts in English translation on the pan-European reception of US art in the Cold War.