DMJ – Canaletto’s Venetian Sketches and the Camera Obscura

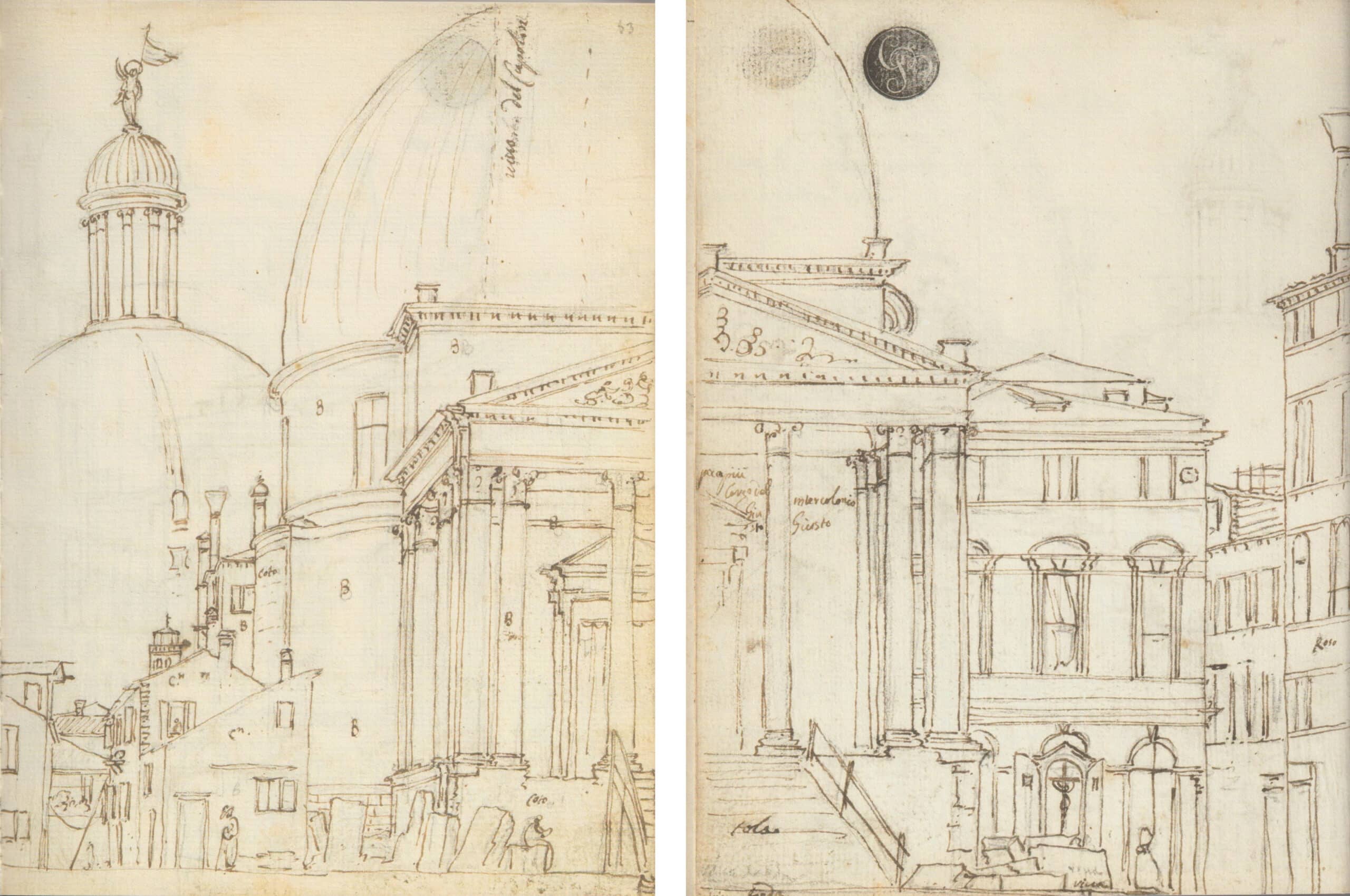

Antonio Canaletto used a camera obscura to make careful sketches of the buildings of Venice. The Gallerie dell’ Accademia has a quaderno, a notebook containing 140 pages of these sketches, which provided the raw material for paintings made in the 1730s, as well as finished drawings that Canaletto offered for sale. This paper analyses the sketches by superimposing them digitally over one of the paintings and over a series of photographs taken specially in Venice from Canaletto’s viewpoints.

In the collection of the Correr Museum there is a small box-type camera obscura with the name ‘A CANAL’ stamped on the top. This may well have belonged to the artist. But he could not have used it for making the quaderno sketches. For these he would have needed a larger instrument in the form of a booth or tent, which he worked inside. Experiments with a reconstructed eighteenth-century design of tent camera show that making sketches which are—at least technically—similar to Canaletto’s, presents no great problems.

Venice has changed little since Canaletto’s time. This means that it is possible to compare his sketches with the real architecture of the city. Superimpositions over photographs show the sketches to be, in general, extremely accurate. Examples are illustrated of the church of San Simeone Piccolo, and the Gates of the Arsenal.

By comparing the sketches with the paintings and finished drawings it is possible to show what changes Canaletto then makes to the real views for compositional reasons. A painting of the Campo SS Giovanni e Paolo is analysed in detail. This reveals that Canaletto raises the dome of the church, adjusts the heights of other buildings, rotates the west front of the church so that it is seen frontally not obliquely, and in effect combines views from two positions into this single picture. These are all gambits used in other works.

Canaletto lies in a tradition of view painting with the camera, stretching from Vermeer’s View of Delft and the Amsterdam artist Jan van der Heyden, through the Dutch/ Italian painter Vanvitelli, to Canaletto’s nephew and assistant Bernardo Bellotto. Two contemporaries who followed and possibly worked with Canaletto were Michele Marieschi and Francesco Guardi. Both were camera users, both made paintings of SS Giovanni e Paolo. Marieschi’s version is a faithful copy of the Canaletto. Guardi, surprisingly, paints the view exactly as seen in a photograph, with none of Canaletto’s alterations and transformations.

Download the full article as a printable PDF

DMJournal–Architecture and Representation

No. 2: Drawing Instruments/Instrumental Drawings

Edited by Mark Dorrian and Paul Emmons

ISSN 2753-5010 (Online)

ISBN (forthcoming)

About the author

Philip Steadman is Emeritus Professor of Urban and Built Form Studies at University College London. He trained as an architect and has taught at Cambridge University and the Open University. In the 1960s he co-edited and published Form, a quarterly magazine of the arts. He has contributed to numerous exhibitions, films, and books on perspective geometry and the history of art. In 2001 he published Vermeer’s Camera (Oxford University Press), on the Dutch painter’s use of the camera obscura. The full-length documentary film Tim’s Vermeer (Sony Pictures, 2014) was largely inspired by Vermeer’s Camera. In 2022 he was awarded an Emeritus Fellowship by the Leverhulme Trust for a project on Canaletto and the camera obscura, of which this paper is one product. He is working on a book to be called Canaletto as Photographer.

Click here to receive updates about the journal, and future calls for abstracts.