El Croquis 208: DOGMA familiar/unfamiliar 2002–2021 (2021): Review

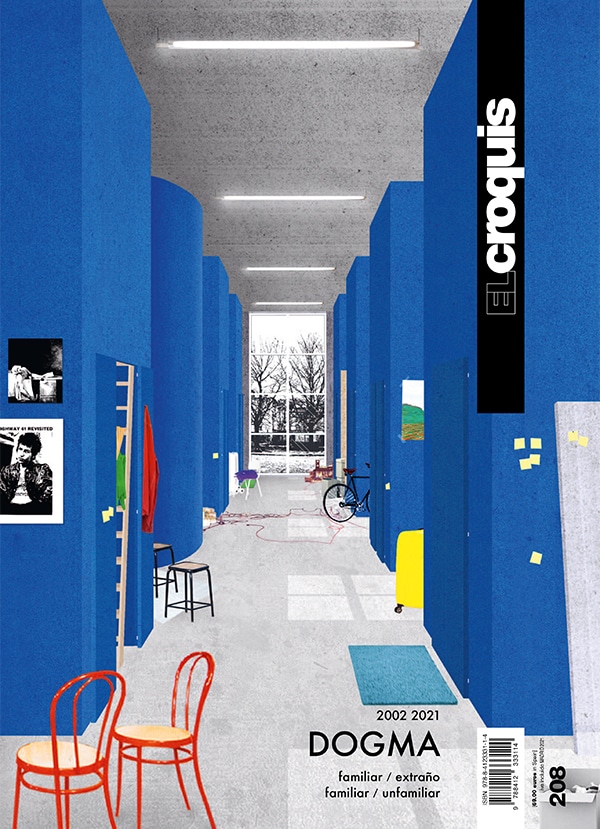

As one of the most prominent architecture publications in the world, El Croquis has long been a prestige showcase for the upper echelon of architectural practices. Its publication format, with each issue typically devoted to a specific practice, lends El Croquis more the air of an exclusive monograph series than we would expect from a traditional architecture magazine. The vestigial trade ads adorning the opening pages continue to remain a jarring inclusion into what is an otherwise expensive publication. With multiple Pritzker prize winners and practices that would comfortably fit into the category of starchitect, the magazine boasts an enviably exclusive roster of architecture practices in its annals, to which the inclusion of the Brussels-based architectural practice Dogma marks a shift in the sensibilities of the magazine. Founded and led by Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara, Dogma had virtually no built work to its name at the time of publication and the practice is best known for its polemical writings and intricate drawings and collages.

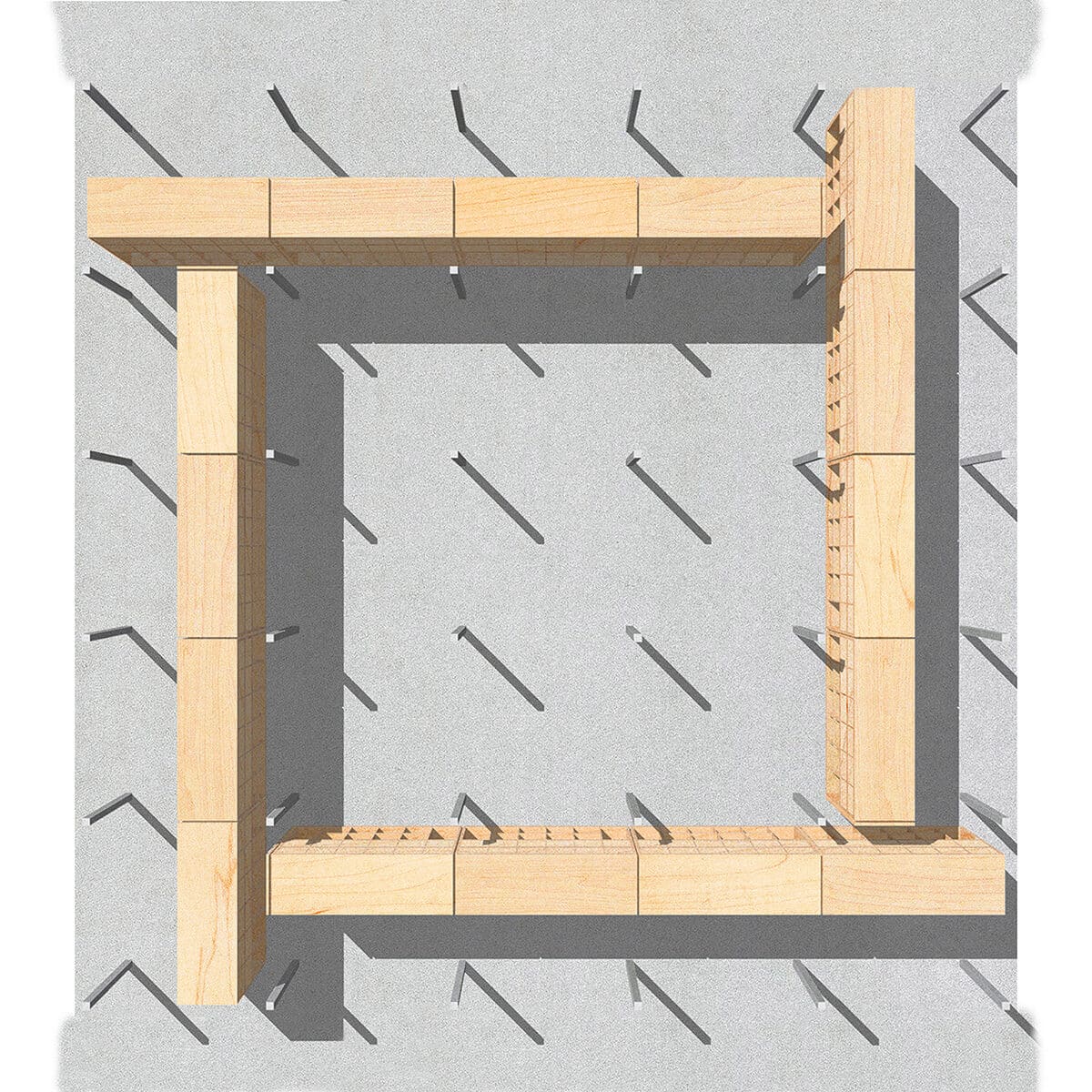

Dogma rose to prominence at the turn of the millennium with a series of theoretical texts and projects that stood in marked contrast with the post-critical fascination with informality and complexity of the late 1990s. Their genesis can be traced back to two overlapping agendas in architecture: the possibilities of architectural form to limit and frame space; and the changing working conditions of capitalist society, exemplified in two early projects: ‘Stop City’ and ‘A Simple Heart’. Here, Dogma stake out their political ambition for architectural form, laying claim to an idea of the city within and against the neoliberal processes of urbanization. [1] Both projects have been widely published, most notably in Dogma’s first monograph of 11 projects (AA publications, 2013). El Croquis 208 includes these two key projects but omits their conceptual foundations from the project texts. In the case of ‘Stop City’, the original project text included references to Paolo Virno and Carl Schmitt that laid out the stakes for what is otherwise an extremely formal proposal for eight 25-m deep slabs, each measuring 500m x 500m, arranged around a square forest. It offered a compelling critique of the contemporary fascisms of flexibility in informal urbanism and a broader political conception of form as a limit to the economic. [2] While references to Ludwig Hilbersheimer’s ‘Hochaustaadt’ (Vertical City) and Archizoom’s ‘No-Stop City’ remain in the El Croquis version, the tenor of the project slips into a heroic exercise in abstraction.

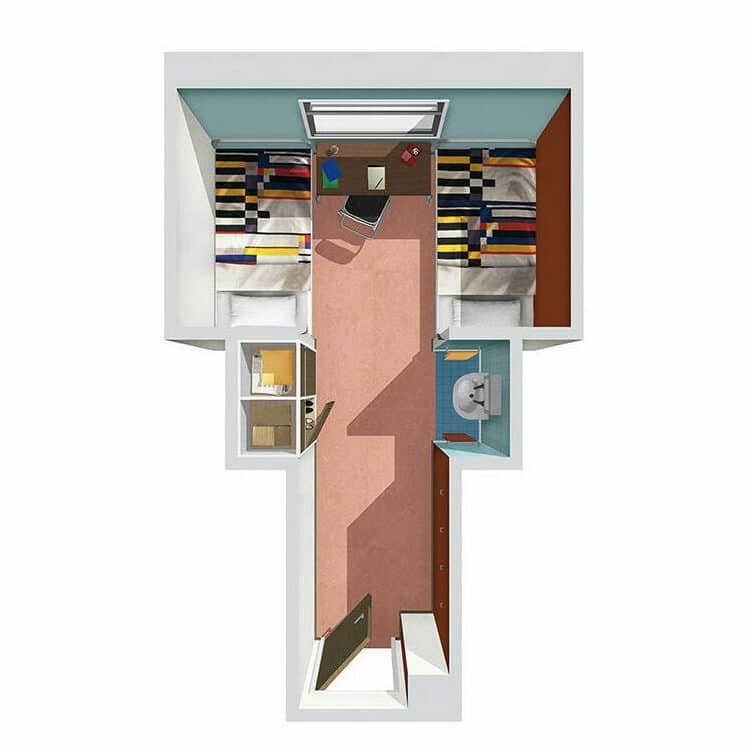

Although ‘A Simple Heart’ remains rooted in the changing working conditions of the Post-Fordist turn, mention of Cedric Price’s ‘Pottery Thinkbelt’ as a key reference that explored the relationship between education and production has been removed entirely. [3] Deliberate or not, the decision to omit these formative references undermines what has made Dogma such an exciting and polemic practice. While it could be argued that El Croquis caters to a less academic, more practice-focused audience, the significance of Dogma’s projects has always resided less in their absolute architectural form and more in their didactic potential. The early projects of Dogma were catalysts for provocative texts that connected architecture with key thinkers of philosophy and politics.

It is a testament to Dogma’s talents that these key concepts can been so easily excised from their work. Within the space of contemporary architecture, Dogma is almost without peer in their ability to combine both rigorous and critical writing with distinctive drawings and collages that could easily pass as an artistic signature. Their representations have been a deliberate flirtation with novelty from their early days at the Berlage Institute, where they turned to formalistic ‘tricks’ such as photocopier effects to communicate the ethos they were trying to advance. [4]

Perhaps the most interesting inclusion in El Croquis 208 is the essay ‘Paint a Vulgar Picture’, in which Aureli and Tattara delve into the history and use of their distinctive collage techniques. Shying away from the use of computer-generated renderings, the ‘photoshop collage’ was developed during their time at the Berlage with Elia Zenghelis and other collaborators. Their role in affirming the post digital drawing is a surprising admission for a practice that seems uninterested with the trappings of fame and recognition. However, this necessary and timely essay goes some way to recuperating Dogma’s commitment to architectural representation as ‘real abstractions’, able to address architecture as built form, yet retaining their status as images.

There is a comforting appeal to Dogma’s project, at once countering the stylistic excesses of the starchitect era while still engaged with the production of architectural form. Yet Dogma’s popularity has become a double-edged sword. It has become worryingly easy today to signal one’s good intentions with photoshopped collages, square cropped drawings and single-point perspectives. Such stylistic tributes could be driven by such diverse motivations as a theoretical engagement with Dogma’s work, or an antagonism to the glossy renderings of real estate marketing, or even millennial aesthetic sensibilities shaped by Instagram and Wes Anderson films. The risk of subsumption, therefore, remains an underlying tension to Dogma’s work, and the limits to the political project of the ‘architecture of limits’ have been called out by various critics. [5] For Douglas Spencer, the act of separation between the political and the economic is based on formalistic premises that obscure the ways in which the ‘redemptive project of the autonomous self is also mediated by the economic and managerial imperatives of neoliberalism’. [6] On the part of Tahl Kaminer, the positing of the limit and the isolated fragment as a political act is a revival of critical tendencies that harken back to an era of architectural autonomy that has already been defanged. [7]

Against the smooth parametric forms and participatory spectacle of the informal, the complex and the flexible, the (re)assertion of architectural form appears to break new ground, but only over familiar territory. Indeed, Peter Eisenman was a member of Aureli’s PhD defence committee, and no doubt recognizing an affinity with his own project of autonomy, shepherded through what would eventually be published by MIT Press as The Possibility of Absolute Architecture. [8] But if the autonomy of Eisenman’s era was heroic, a triumph of the artistic will against the demands of clients and budgets, the conspicuous lack of built work in El Croquis 208 may indicate a tacit retreat in what constitutes a legitimate architectural practice today. For a publication typically reserved for practices with a substantial oeuvre of realised projects, the inclusion of Dogma is also a recognition of sorts that built work is contingent on political and economic forces that are far more powerful than the individual will of the architect.

It would be a mistake, however, to consider Dogma as upstart outsiders to the architectural scene. Aureli and Tattara hold an enviable pedigree and could comfortably work only as academics and theorists. What is remarkable is that they remain committed to architectural practice through a period of extreme professionalization. A period that witnessed a rapid shift in computer-based methods of drawing and eventually BIM, EU procurement requirements, and the increasing consolidation of architectural practices into mega-corporate entities. Yet, looking at Dogma within the framework of El Croquis we do not see the self-assured theorists and educators taking a victory lap, but rather a young office that is no longer so young toiling away at meticulous (and extremely labour intensive) drawings, competing for the same projects as their professional colleagues. If there is a project of architectural autonomy at work, it is not the autonomy of the 90s that was so easily commodified into an architect’s signature. [9] For Dogma, the square is not a signature, but rather a ‘dogma in the sense that we do not even discuss the why. We simply use it and thereby skip that humiliating moment for architects that they have to desperately search for some interesting form’. [10]

El Croquis 208 compiles together for the first time Dogma’s most significant commissioned projects and constitutes a generous contribution from a practice that often shies away from presenting their practice-based work. Though Aureli’s and Tattara’s writings are often engaged in a political critique of architecture, both are reluctant to have their architecture seen as an answer to that critique. Within the sleek and glossy pages of El Croquis, it is in the, at times, awkward commitment to a strict formal vocabulary in the face of demands of clients and stakeholders that we see the openness of Dogma, where their vulnerabilities are laid bare for all to see. For all the seriousness and clarity of their research and writing, there is a light heartedness to their projects, which often use titles that reference the music of their formative years. Although these projects will now live on in the annals of El Croquis, they seem less answers than scars borne out of the cut and thrust of a practice that continues to grapple with their political critique of architecture.

As architects are called to account for their complicity in capitalist development and challenged to answer increasingly urgent demands of equity and the climate crisis, there is a certain melancholy with which architecture has been set aside. What is architecture for? At once everything and nothing – the lasting legacy of Dogma will be a reinvigorated assertion that ‘architecture needs only to be itself’ to face these challenges. [11] The dogma of Dogma may be that they cannot help but look at the world through the lens of architecture. This is not an affirmation of architecture’s significance, but rather as a particular vantage point through which the world can come in to focus.. Where the architecture of the limit draws a line without a need to determine how the space will unfold, so too does the gap between architecture as theory and architecture as practice make a scaffold through which we can glimpse the terrain for action.

El Croquis 208: DOGMA familiar/unfamiliar 2002-2021 (2021) can be found here.

Leonard Ma is a Canadian architect based in Helsinki. He is a member of the New Academy and teaches at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

Notes

- Aureli and Tattara, ‘Architecture as Framework: The Project of the City and the Crisis of Neoliberalism’, New Georgraphies (Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2009), p.39

- Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara, Dogma: 11 Projects (AA Publications, London: 2013), p.10.

- Idib. p.20

- Pier Vittorio Aureli Interviewed by 0300TV, ARQ Ediciones 2010, p.26

- See, William Hutchins Orr, Counterrealisation: Architectural Ideology from Plan to Project, PhD thesis (The Open University, 2019).

- Douglas Spencer, ‘Less than Enough: A Critique of Aureli’s project’, This Thing Called Theory by Teresa Stoppani, Giorgio Ponzo, and George Themistokleous (Routledge, 2016), p.286.

- Tahl Kaminer, ‘Von Ledoux bis Mies: the modern plinth as isolating element’, arq: Architectural Research Quarterly, (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- ‘Arguments: Towards a Critical Project’, Revista de la Facultad de Arquitectura, Diseño y Urbanismo, [en línea] (Udelar, n.17: 2019) pp.186-187.

- Mary Mcleod, ‘Architecture and Politics in the Reagan Era: From Postmodernism to Deconstructivism’, Assemblage (The MIT Press, No. 8, Feb., 1989).

- Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara, Dogma: 11 Projects, (AA Publications, London: 2013), p.5.

- Aureli and Tattara, ‘Architecture as Framework: The Project of the City and the Crisis of Neoliberalism’, New Georgraphies (Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2009), p.39.