Fabric Object: Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas

– Darell Wayne Fields, Anda French, Tessa Kelly, Paul Lewis and Michael Meredith

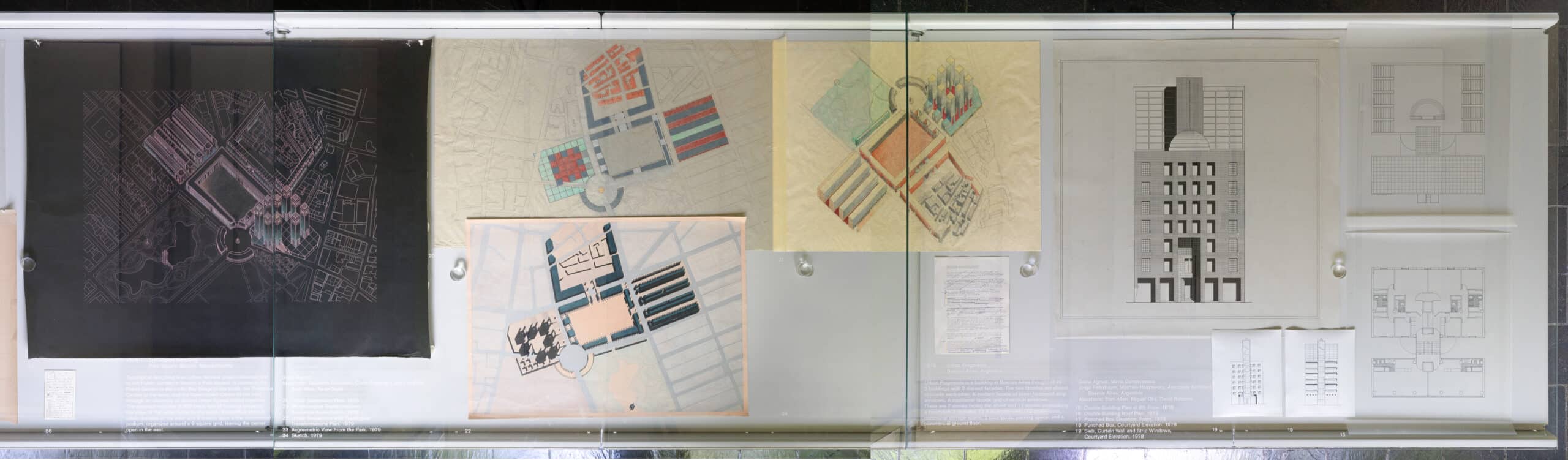

The small exhibition Fabric Object, curated by Michael Meredith and exhibited at the Princeton University School of Architecture between 7th March and 3rd May 2024, brought together seven projects from the early career of Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas, of Agrest and Gandelsonas Architects. Short texts written by the Princeton School of Architecture faculty: Stan Allen, Sylvia Lavin, Jesse Reiser, Tessa Kelly, Marshall Brown, Darell Wayne Fields, Anda French, Paul Lewis, Erin Besler, Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley were also included in the curation of the exhibition.

Through three posts, Drawing Matter revisits the seven projects from the early career of Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas and the texts written by the Princeton School of Architecture faculty. The first post can be found here.

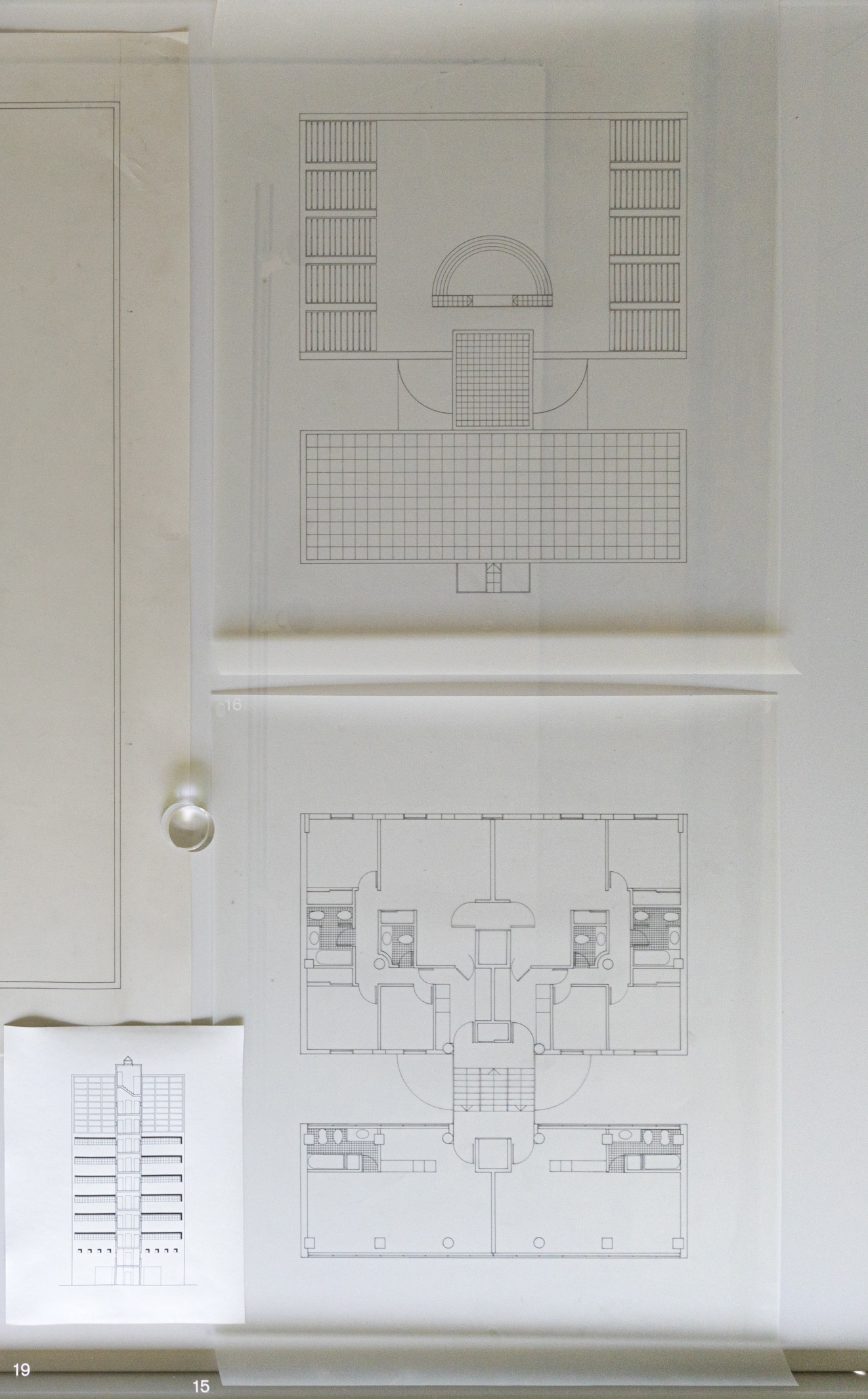

This second post presents the projects: Typological Morphing, Park Square, Boston, Massachusetts, 1979 and Urban Fragments, Building 1, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1978 through Anda French’s, Darell Wayne Field’s, Tessa Kelly’s and Paul Lewis’s reflections.

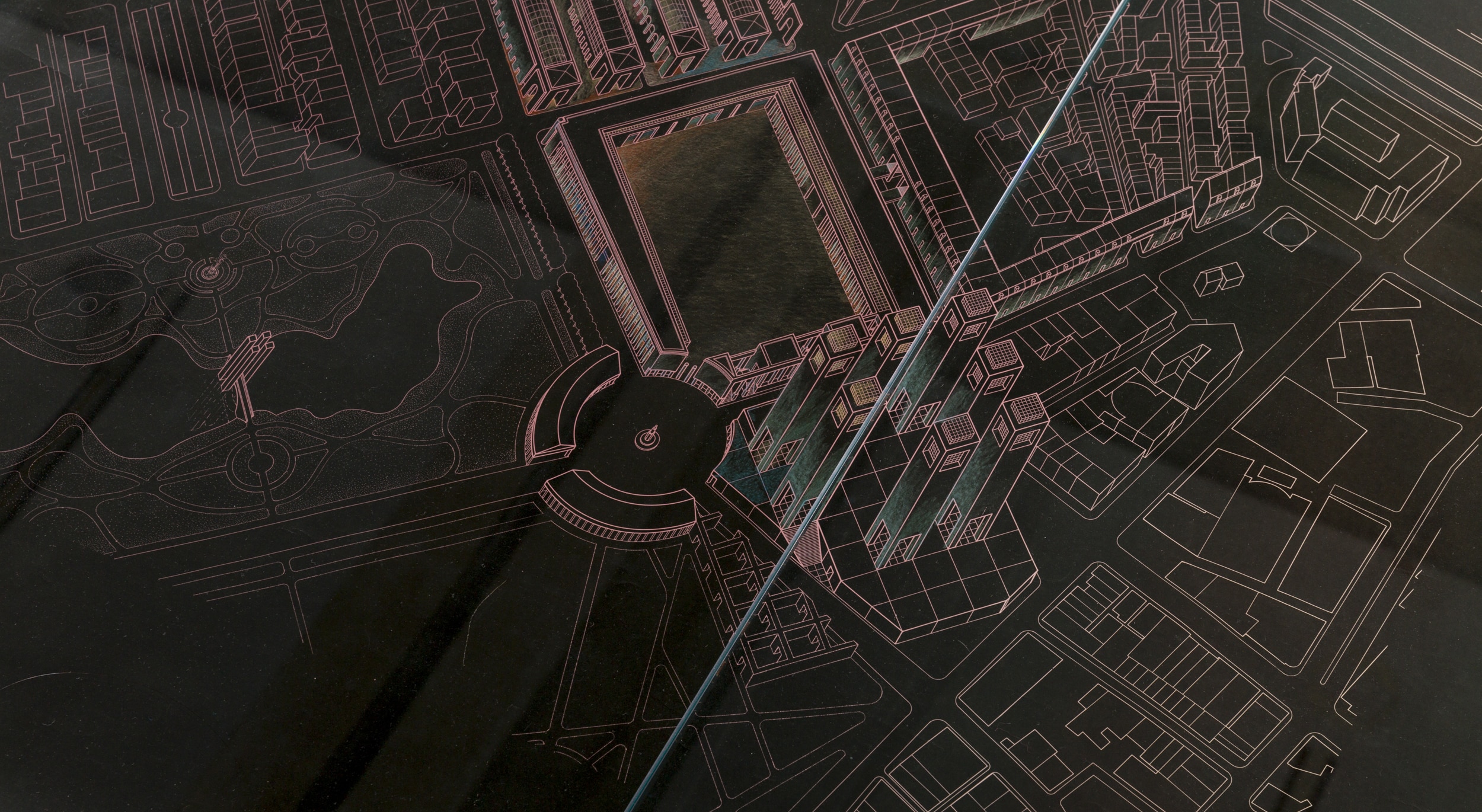

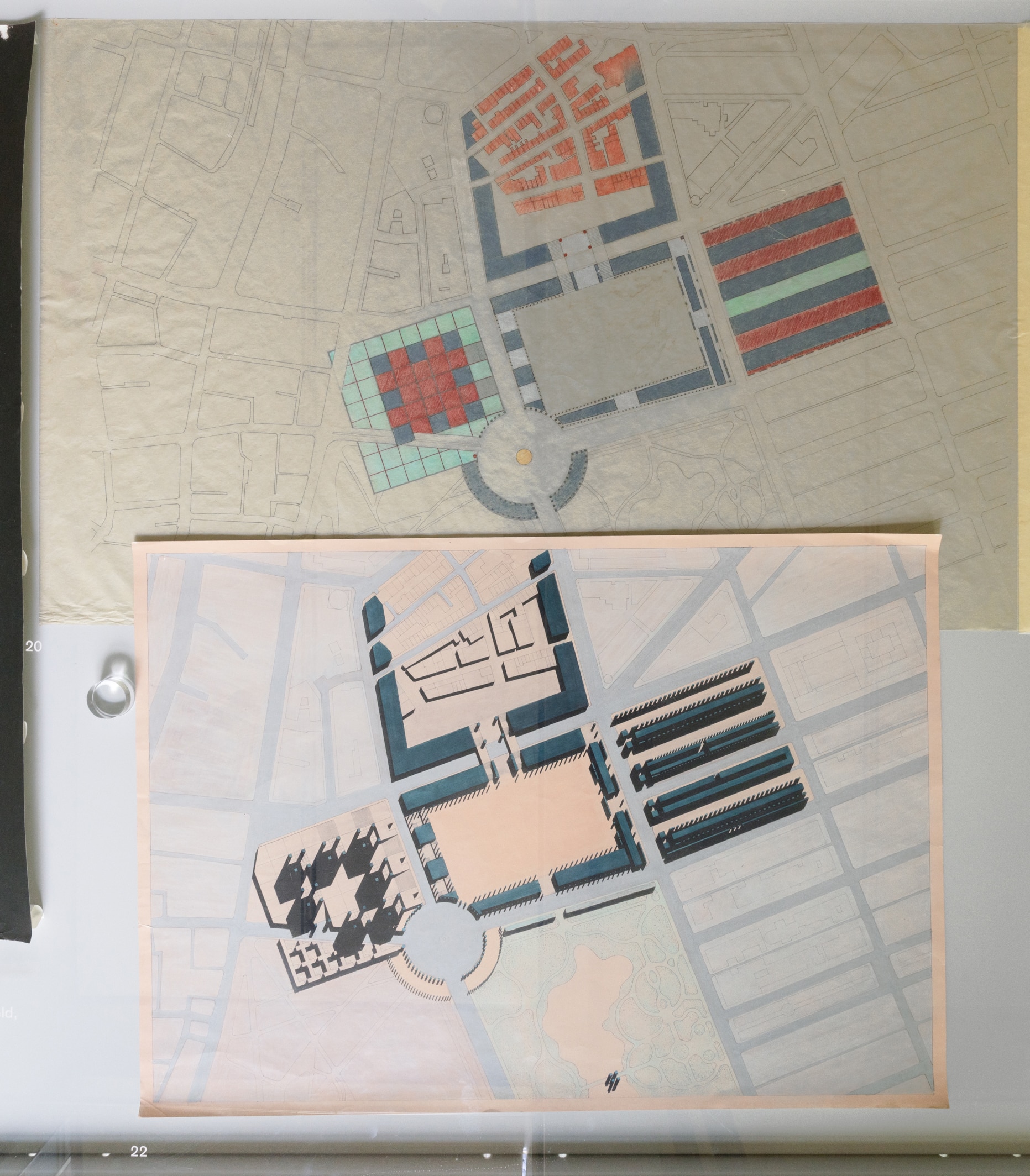

Park Square by Anda French

I might be generationally guilty of a reductive shorthand definition of the autonomous project—one in which architecture is agnostic to the cultural realities of the city. But a closer reading of Agrest and Gandelsonas’ Park Square project has inspired a personal reflection and a revisiting of the nuance of autonomy in practice and product. At this key intersection of neighbourhoods in Boston, where scale, history, and pattern seem incongruous, the project mobilizes a critical reading of urban forces by identifying coded terms within the existing urban fabric. Most interestingly, it does not do so to contradict, obliterate, and recreate, but rather to participate, synthesize, and project. Through a tension between the plan and the axonometric, Agrest’s distinction between the ‘productive’ vs. the ‘destructive’ use of the tabula rasa is beautifully apparent; while the plan diagrammatically reduces the urban context to pattern and linear relationships across parcels, reinforcing the seeming simplicity of clearing and reconstructing, the sectional qualities and intricacies of scale and more complex unfolding of codes across the axon tell a different story. The project is not indifferent to the cultural logic of the city. Instead, it is able to respond and produce ‘realities’ and ‘fictions’ on architecture and urbanism’s own terms. The sensitivity to the historical social forces embedded in the various typological movements surrounding the site is apparent in the care with which the project responds to and creates asymmetries and complexities in plan and section.

Theory vs Theory by Darell Wayne Fields

Architectural theory was flat prior to Agrest’s and Gandelsonas’s seminal text Semiotics and Architecture: Ideological Consumption or Theoretical Work.

Theory was not flat like orthographic drawings where plan and section cuts hide what is below, above, front, and back. Rather, architecture’s take on semiotics, professed by theorists prior to 1973, was (and remains) an ideological conflation of sign and communication theories. A&G called out the error, arguing that signs are not synonymous with communication. Unlike language, signs are not constrained to the spoken word or confined to the flatness of writing on a page.

Reading Semiotics and Architecture inspires a question: ‘What happens if a word is turned on its side like the object that it is?’ The question is not rhetorical. A&G are, in fact, describing what signs do.

To demonstrate, A&G signify on the word ‘theory’. ‘Theory’ is doubled and split in two. One ‘theory’ is adaptive (flat), seemingly leaving the ideological misreading intact. The other ‘theory’ is theoretical. Its orientation, relative to adaptive ‘theory’, is turned on its side, resulting in a perpendicular and vertical relationship. Verticality, according to A&G, signifies theoretical trajectories free of ideology. Because the two theories share an axis of rotation, distinguishing ‘theory’ (adaptive and ideological) from ‘theory’ (proactive and vertical) is a limitless critical project.

A&G’s theoretical distinction is offered in plain sight. Shifting back-and-forth, between ‘theory’ and ‘theory’ signals the virtue of vertigo—theory’s disorientation is disruptive and full of risks. Ideology is just flat.

A&G’s interpretation of semiotics is more spatial than literary. The signifying principle used to distinguish ‘theory’ from ‘theory’ is one of orientation versus meaning. Their translations (doubling, splitting, and rotating) are more akin to manoeuvring and representing complex (sign) objects. Thus, the term ‘architecture’ in Semiotics and Architecture signifies a (vertical) shift from the etymological to the orthographic, from language to space.

Now, imagine the unexpected theories freed from ideology when making a perpendicular cut through the arbitrary nature of the sign.

7 Questions about Urban Fragments: Building 1 by Tessa Kelly

- Diana and Mario, as young architects designing housing in your shared native city of Buenos Aires, what hopes did this project seek to inspire or communicate?

- In 1977, Argentina’s inflation rate was the highest in the world. Civil service workers earned minimum wage and were on strike throughout the country. Was the project related to, driven by, or a response to any of these social pressures?

- Who commissioned this project, and how did they partner with you?

- Were there elements of the urban context of your home city that you came to see in a new way?

- Did you feel the need to speak two languages with this project? One for your international community of architects, considering your experience in New York and Paris, and another for your home community in Buenos Aires, with a different set of lived priorities and values?

- How would you differentiate the goals of the drawing project and the goals of the construction project?

- What specific experiments or experiences with Urban Fragments Building 1 went on to shape your future work?

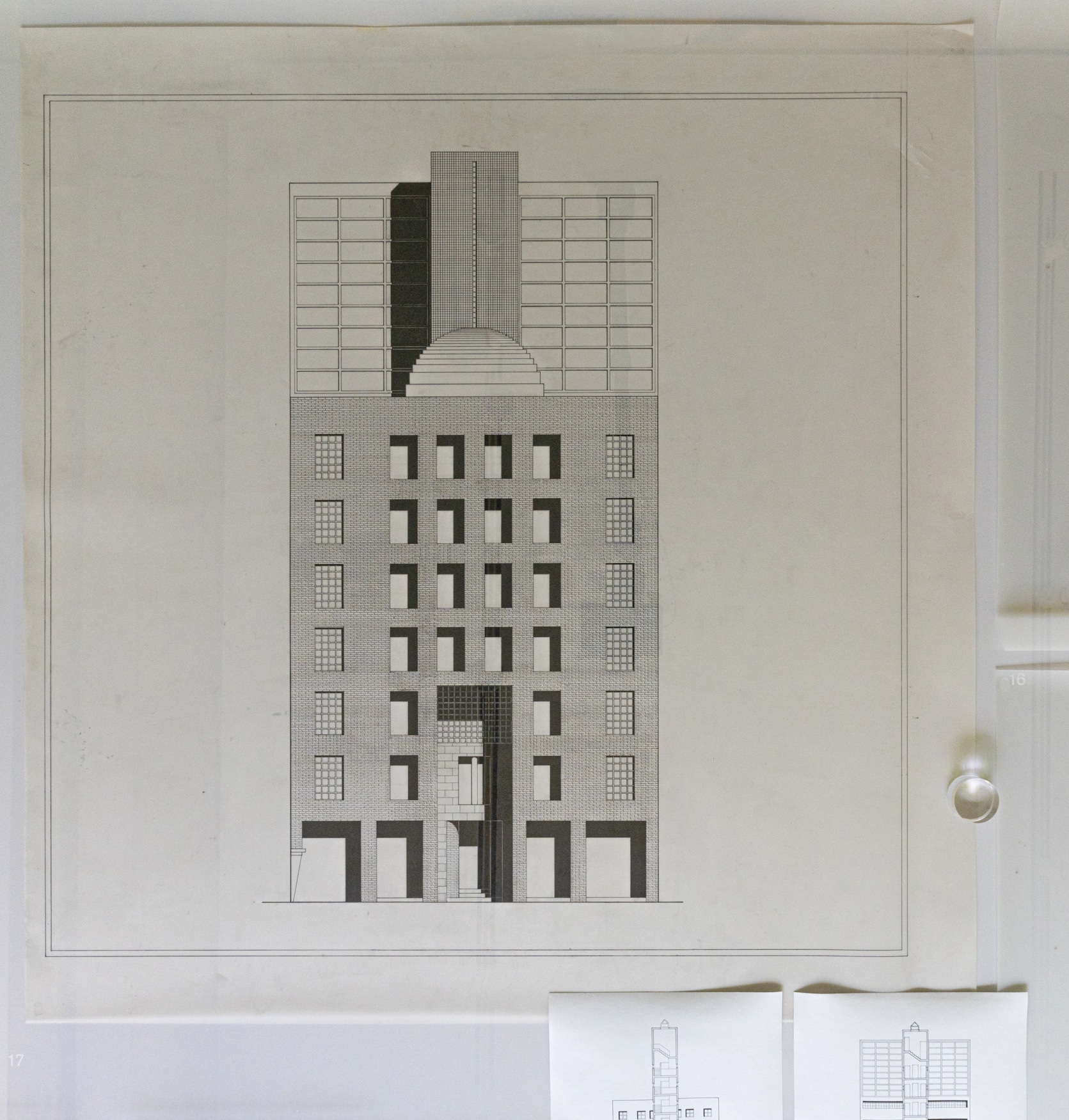

AG Building 1 by Paul Lewis

A+G’s Building 1 is more peculiar as a building than its drawings might suggest, and much of its qualities relate to its physical skin. It’s a brick screen devoid of any other detail beyond common bricks and mortar (not a single brick was cut or harmed in the process.) There are no control joints, expansion joints, window sills, lintels, flashing, or any other visible attempts to deal with how it works with other building components. Indeed, it is unclear how this envelope even makes an enclosure against the weather. Yet it appears to be no thin brick veneer as it is always at least three wythes thick, and at the very large entry is nine wythes invoking Monadnock-like load-bearing capacity.

Moreover, although the elevation is composed of punched windows to frame views into and out of the building, this depth produces shadows that nearly erase what occurs beyond this elevation as mass. Balconies project not out but into the apartments. Nevertheless, from an oblique view at a bit of distance, the party wall doesn’t extend this mass but is detailed to be distinctly separate and registers the façade as an independent clipped-on plane, despite that it too is also brick. This front surfaces a building volume, which itself fronts another larger building volume to the rear of the site. Oh, and despite the relentless axial symmetry of this brick front, it is missing the base of its far left column, which rests on a short, pink plaster stub that must have been there all along, certainly before Building #1.

Diana Agrest is a Professor of Architecture at The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture of The Cooper Union for Advancement of Science and Art. She is a founder and principal of Agrest and Gandelsonas Architects in New York, while she also develops her own individual projects.

Mario Gandelsonas is an architect and theorist whose specializations include urbanism and semiotics. Gandelsonas is a Professor of Architectural Design at the Princeton University School of Architecture, and with Agrest, he is a founding partner of Agrest and Gandelsonas Architects.

Michael Meredith is a Professor of Architectural Design at the Princeton University School of Architecture. Along with his partner, Hilary Sample, Meredith is a principal of MOS, based in New York. His writing has appeared in Artforum, LOG, Perspecta, Praxis, Domus, Harvard Design Magazine.

Anda French is a Visiting Lecturer at the Princeton University School of Architecture and the co-founder with Jenny French of French 2D, a Boston-based architecture and design studio.

Darell Wayne Fields is a teacher, designer, and scholar. He has taught design, urbanism, and theory at several universities, including Harvard Graduate School of Design, California College of the Arts (San Francisco), and the University of California Berkeley. Fields was a Visiting Presidential Scholar at Princeton for 2021-2022.

Tessa Kelly is a co-founder of Group Architecture and Urbanism (Group AU), as well as co-founder of The Mastheads, a public design non-profit in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. She is currently teaching at the Princeton School of Architecture.

Paul Lewis, FAIA, is a Principal at LTL Architects based in New York City. He is currently a Professor at Princeton University School of Architecture, where he has taught since 2000.